Hague Abduction Convention in Japan: Supreme Court Prioritizes Children's Welfare Amidst Changed Circumstances

Date of Decision: December 21, 2017

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

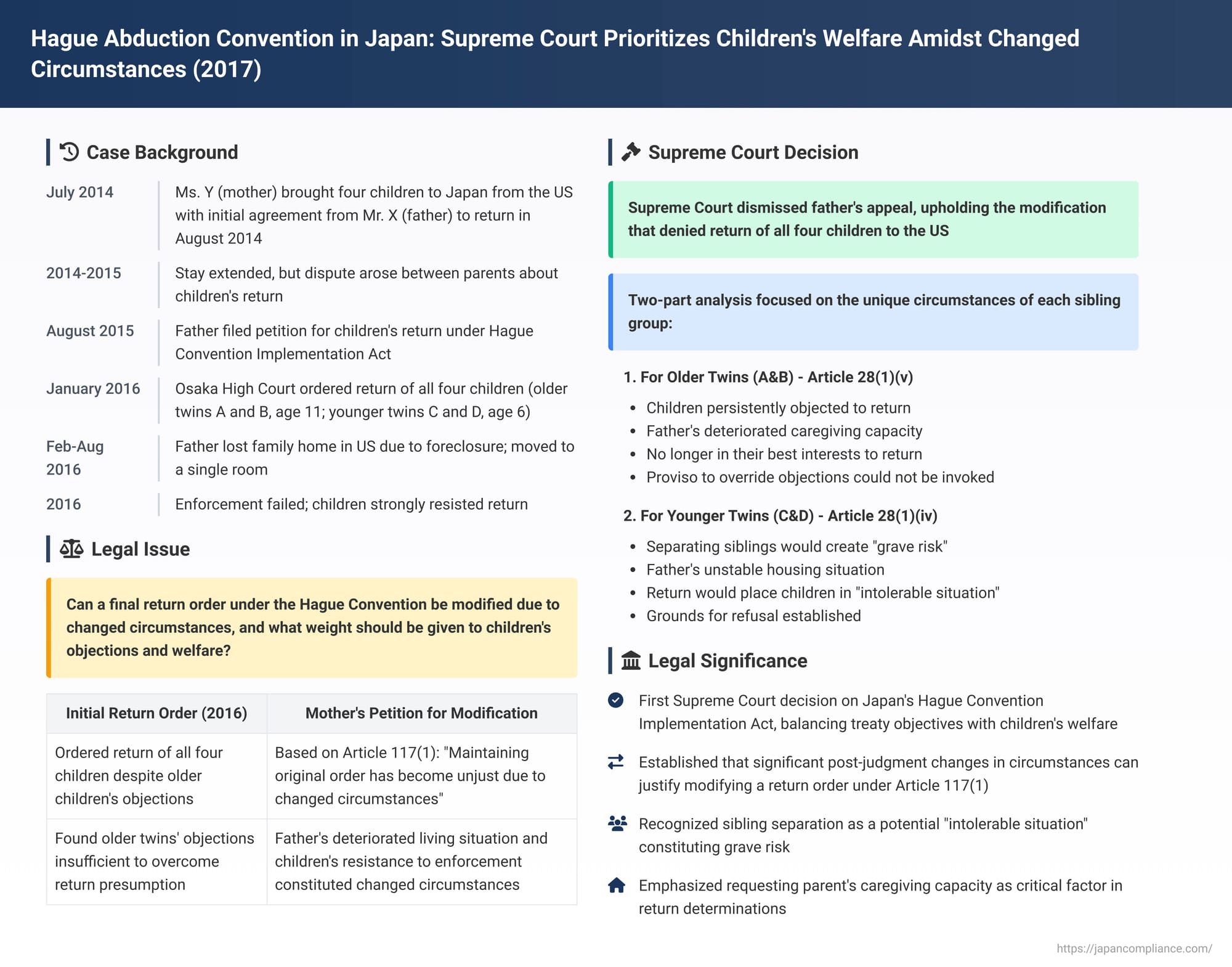

The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction is a multilateral treaty designed to ensure the prompt return of children wrongfully removed to or retained in a contracting state, with the underlying principle that custody disputes should generally be resolved in the child's country of habitual residence. This Japanese Supreme Court decision from December 21, 2017, marks its first ruling on Japan's Act for Implementation of this Convention ("Implementing Act"). The case involved a father seeking the return of his four children from Japan to the United States, and the Court's decision hinged on significant changes in circumstances and the children's well-being.

The Factual Background: A Family Divided Across Continents

The case involved a family with roots in both the United States and Japan:

- Mr. X (the husband/father) and Ms. Y (the wife/mother) lived with their four children in the United States. The children included older twins, son A and son B (then 11 years and 7 months old), and younger twins, daughter C and son D (then 6 years and 5 months old).

- In July 2014, Ms. Y brought the four children to Japan. She had agreed with Mr. X that they would return to the U.S. in August 2014.

- However, the stay was extended. Mr. X initially told Ms. Y she could remain in Japan with the children beyond September 2014, and he consented to their enrollment in an international school in Japan.

- Subsequently, a dispute arose between the parents concerning the children's return to the U.S.

- In August 2015, Mr. X filed a petition under Article 26 of Japan's Implementing Act, seeking a court order for the return of all four children to the United States.

- During the court proceedings, a family court investigator interviewed the children. The older twins, A and B, strongly expressed their refusal to return to the U.S. The younger twins, C and D, also indicated reluctance. All four children emphasized their desire not to be separated from their siblings.

- Mr. X's financial situation was precarious; he reportedly lacked a stable economic foundation to adequately care for the children in the U.S. and had no reliable prospects of ongoing support from relatives.

The Initial Court Order and Its Aftermath

- The Osaka High Court's Initial Return Order (January 2016, "Prior Order"):

- For the older twins, A and B, the High Court acknowledged that a ground for refusal existed under Article 28(1)(v) of the Implementing Act (the child objects to return, and is of an age and degree of maturity at which it is appropriate to take account of their views). However, the court invoked the proviso to Article 28(1), which allows a return order despite such an objection if returning the child is deemed to be in their best interests.

- For the younger twins, C and D, the High Court found no grounds for refusal. It deemed them not sufficiently mature for their objections to be decisive under Article 28(1)(v). It also did not find a "grave risk" that returning them would expose them to physical or psychological harm or otherwise place them in an "intolerable situation" under Article 28(1)(iv).

- Consequently, the High Court ordered all four children to be returned to the United States. This decision became final in the same month.

- Significant Changes in Mr. X's Circumstances:

- After the Prior Order was finalized, Mr. X's situation in the U.S. worsened. In February 2016, the U.S. home where the family had lived was foreclosed. By August 2016, Mr. X had to vacate the property and was living in a single room at an acquaintance's house.

- Failed Enforcement of the Return Order:

- Mr. X attempted to enforce the Prior Order to have the children returned. However, the children strongly resisted returning to the U.S. and refused to meet with him. The enforcement officer eventually concluded that further attempts at enforcement were impossible and would risk causing psychological harm to the older twins, A and B.

The Legal Challenge: Modifying a Final Return Order

Given these developments, Ms. Y petitioned the Osaka High Court to modify its Prior Order. She argued under Article 117(1) of the Implementing Act that due to the significant change in circumstances, maintaining the original return order had become unjust (不当 - futō). The Osaka High Court agreed with Ms. Y, modified its Prior Order, and dismissed Mr. X's initial petition for the children's return. Mr. X then appealed this modification decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Return Denied for All Children

The Supreme Court dismissed Mr. X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision not to return the children to the United States. The Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the change in circumstances and the best interests and welfare of the children:

- Key Finding: Significant Deterioration in Father's Caregiving Capacity: The Court found that Mr. X already lacked a stable financial foundation to properly care for the children even at the time of the Prior Order. His subsequent loss of the family home and inability to secure stable housing constituted a significant deterioration in his capacity to provide care should the children be returned to the U.S. This was a material change in circumstances since the Prior Order.

- For the Older Twins (A and B) - Child's Objection (Art. 28(1)(v)):

- A and B had consistently and strongly objected to returning to the U.S.

- While the Prior Order had acknowledged their objection but ordered their return based on the "best interests" proviso, the Supreme Court found that Mr. X's worsened caregiving situation fundamentally altered this balance.

- The Court concluded that returning A and B to the U.S. under these deteriorated circumstances was no longer in their best interests.

- Therefore, the proviso to Article 28(1) could not be invoked to override their objections. The refusal to return them was upheld.

- For the Younger Twins (C and D) - Grave Risk / Intolerable Situation (Art. 28(1)(iv)):

- Given that their older siblings, A and B, were not being returned, sending only C and D to the U.S. would result in the separation of these closely-bonded siblings.

- The Supreme Court, considering this separation alongside Mr. X's significantly compromised caregiving abilities, concluded that returning C and D would place them in an "intolerable situation" (耐え難い状況 - tae-gatai jōkyō), thereby meeting the "grave risk" (重大な危険 - jūdai na kiken) threshold for refusal of return under Article 28(1)(iv) of the Implementing Act. Their return was also refused.

Understanding Japan's Implementation of the Hague Convention

This first Supreme Court decision on the Hague Abduction Convention in Japan provides important insights into how the treaty and its Implementing Act are interpreted:

- Presumption of Return: The Convention operates on the principle that children wrongfully removed or retained should generally be returned to their country of habitual residence for custody matters to be decided there.

- Grounds for Refusal: However, Article 28(1) of the Implementing Act provides specific, narrowly construed grounds for refusing a return order. Those central to this case were:

- Art. 28(1)(v): The child objects to being returned, provided the child has attained an age and degree of maturity at which it is appropriate to take account of their views. (The commentary suggests around 10 years old is often a benchmark, but individual assessment is key).

- The Proviso to Art. 28(1): Even if a child objects (and certain other grounds are met), the court can still order return if it finds that returning the child is in their best interests (子の利益 - ko no rieki).

- Art. 28(1)(iv): There is a grave risk that return would expose the child to physical or psychological harm or otherwise place the child in an intolerable situation. The Implementing Act (Art. 28(2)) clarifies that in assessing this "grave risk," courts should consider all circumstances, including difficulties the petitioner (requesting parent) or respondent (taking parent) might have in caring for the child in the country of habitual residence.

- Sibling Separation and Caregiving Capacity: The Supreme Court clearly indicated that the potential separation of closely-bonded siblings and the precarious caregiving capacity of the requesting parent are significant factors in determining whether an "intolerable situation" exists.

Modification of Final Orders Due to Changed Circumstances

The case also turned on Article 117(1) of the Implementing Act, which allows for the modification of a final return order if subsequent changes in circumstances render its maintenance "unjust."

- The commentary accompanying the case notes an ongoing interpretive debate about this "unjust" standard. If it simply means that one of the refusal grounds in Article 28 now applies due to changed circumstances, it could potentially allow a party to benefit from delaying tactics, which would undermine the Convention's goal of prompt return. Alternatively, a more restrictive interpretation of "unjust" might be adopted, though this could lead to uncertainty. The Supreme Court in this instance appeared to re-evaluate the Article 28 grounds in light of the father's worsened situation.

Conclusion

This landmark Supreme Court decision underscores a child-centric approach within the framework of the Hague Abduction Convention as implemented in Japan. While affirming the Convention's general aim of prompt return, the Court demonstrated that significant and adverse changes in the requesting parent's circumstances, coupled with the children's objections and the severe negative impact of sibling separation, can constitute valid grounds for refusing a return order. The ruling illustrates the judiciary's careful balancing act between the treaty's objectives and the paramount need to protect children from grave risks and ensure their welfare in highly challenging international family disputes. It also highlights the dynamic nature of such cases, where post-judgment changes can necessitate a re-evaluation of what is truly in the children's best interests.