Habeas Corpus as a Last Resort: Japanese Supreme Court on Enforcing Hague Child Return Orders

Date of Decision: March 15, 2018

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

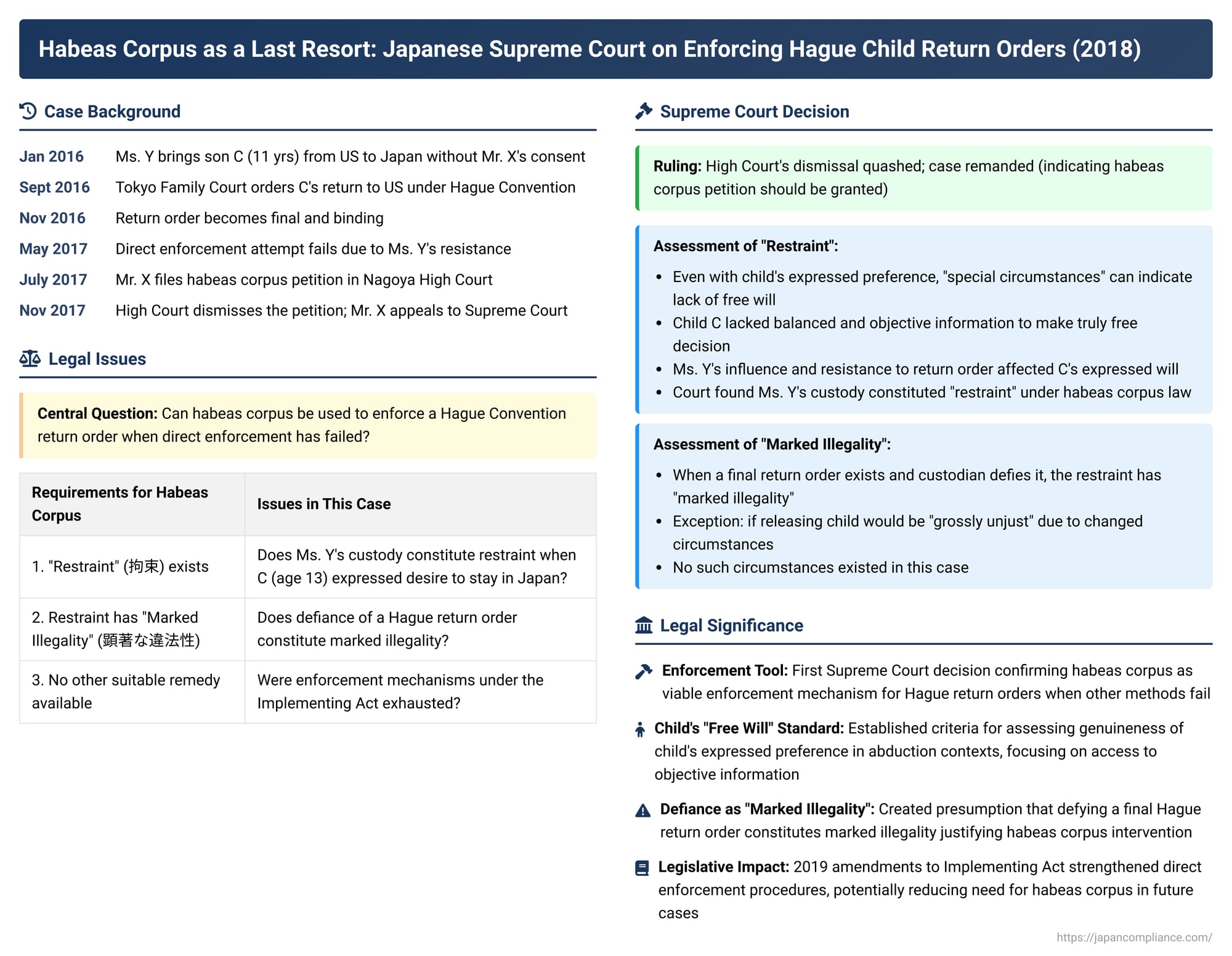

The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction aims to ensure the prompt return of children wrongfully removed or retained across international borders, with the primary goal of having custody disputes resolved in the child's country of habitual residence. Japan enacted an "Implementing Act" to give effect to this Convention. However, what happens when a parent defies a final court order issued under this Act to return a child? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from March 15, 2018, addressed this critical issue, affirming the potential use of habeas corpus proceedings as a means to secure a child's return when other enforcement mechanisms have failed.

The Factual Saga: Abduction, Return Order, and Defiance

The case involved a Japanese couple and their children:

- Mr. X (the husband/father) and Ms. Y (the wife/mother) were Japanese nationals. They had moved from Japan to the United States with their two older children (A and B). Their second son, C (the child subject to the proceedings), was born in the U.S. in 2004, holding dual U.S.-Japanese nationality.

- The parents' relationship deteriorated around 2008.

- In January 2016, Ms. Y, without Mr. X's consent, brought C (then 11 years and 3 months old) from their habitual residence in the U.S. to Japan. Ms. Y and C resided in Japan thereafter.

- In July 2016, Mr. X petitioned the Tokyo Family Court under Japan's Implementing Act for an order compelling Ms. Y to return C to the United States.

- In September 2016, the Tokyo Family Court issued a final decision ordering C's return to the U.S. (the "Return Order"), which became legally binding in November 2016.

- Ms. Y, however, did not comply with the Return Order. Mr. X's attempts to secure C's voluntary return, followed by an application for indirect enforcement (which typically involves financial penalties for non-compliance), were unsuccessful.

- Mr. X then applied to the Tokyo Family Court for "alternative execution" (代替執行 - daitai shikkō), a form of direct enforcement, of the Return Order. The court granted an order for the child's return to be carried out by enforcement officers.

- In May 2017, enforcement officers went to Ms. Y's residence and attempted the "liberation implementation" (解放実施 - kaihō jisshi) – acts necessary to release C from Ms. Y's physical custody as prescribed under the (pre-amendment) Implementing Act. Ms. Y fiercely resisted these efforts. The enforcement officers, concluding that they could not release C from Ms. Y's custody under the circumstances, terminated the enforcement attempt as impossible.

- In July 2017, Mr. X filed a habeas corpus petition (人身保護請求 - jinshin hogo seikyū) with the Nagoya High Court against Ms. Y, seeking C's release.

- During these habeas corpus proceedings (September/October 2017), C, now around 13 years old, met with his own court-appointed legal representative. He expressed a strong desire to continue living in Japan, stating that this was his own genuine wish and not the result of pressure from Ms. Y.

- In November 2017, the Nagoya High Court dismissed Mr. X's habeas corpus petition. Mr. X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

- (Separately, in July 2017, Mr. X had obtained an order from a California Superior Court granting him sole physical custody of C.)

The Legal Question: Can Habeas Corpus Be Used to Secure a Child's Return After a Hague Order Is Defied?

The central issue before the Supreme Court was whether a habeas corpus petition could be granted to enforce a child's return when direct enforcement measures under the Hague Convention's Implementing Act had already proven futile due to the custodial parent's resistance.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Paving the Way for Habeas Corpus

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's dismissal and remanded the case (which, on remand, led to the High Court granting Mr. X's petition). The Supreme Court's reasoning carefully analyzed the requirements for habeas corpus in the specific context of international child abduction:

1. Determining "Restraint" (拘束 - kōsoku) of the Child:

A fundamental requirement for habeas corpus is that the person is being unlawfully "restrained." The High Court had found no restraint, considering C's expressed desire to stay in Japan. The Supreme Court disagreed:

- General Principle for Children with Decisional Capacity: The Court referenced its own 1986 precedent: even if a child has the capacity to make decisions (generally around age 10 or older, depending on maturity), their custodian's care can constitute "restraint" if special circumstances indicate the child is not staying with the custodian based on their own free will (自由意思 - jiyū ishi).

- Special Considerations in International Child Abduction Cases:

- The decision for an abducted child about where to live is exceptionally grave and complex, impacting their future home country and potentially their nationality (if a dual national).

- Such abductions typically occur amidst severe parental conflict, making it difficult for the child to maintain contact with the left-behind parent and forcing them into an unfamiliar linguistic and cultural environment.

- Consequently, abducted children often struggle to obtain the balanced, multifaceted, and objective information necessary to make such a critical life decision freely.

- Assessing "Free Will": To determine if a child's expressed preference is genuinely based on free will in these abduction scenarios, courts must meticulously examine:

- Whether the child has access to sufficient multifaceted and objective information, considering the decision's gravity.

- Whether the abducting parent is exerting undue psychological influence over the child.

- Application to Child C:

- C, at 13, was deemed to have decisional capacity.

- However, he had lived in the U.S. until he was over 11, lacked a prior life foundation in Japan, and was not fully equipped to assess such complex issues when brought to Japan. He had limited communication with his father (Mr. X) since arriving in Japan and was highly dependent on his mother (Ms. Y).

- Critically, Ms. Y had demonstrated a clear refusal to comply with the final Return Order and had vigorously resisted the enforcement attempts in C's presence.

- The Supreme Court concluded that, due to these circumstances, C was in a situation where it was difficult for him to obtain the necessary objective information to freely decide whether to remain with Ms. Y (including understanding the implications of the Return Order and life in the U.S. post-return). Furthermore, Ms. Y was found to be exerting undue psychological influence.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that special circumstances existed indicating C was not staying with Ms. Y based on his own free will. Ms. Y's custody of C did constitute "restraint" for the purposes of habeas corpus.

- As C's expressed will was not deemed free, Mr. X's habeas petition was not considered to be contrary to C's "freely expressed will" (a condition that could bar a habeas claim under Habeas Corpus Rules Art. 5).

2. Determining "Marked Illegality" (顕著な違法性 - kencho na ihōsei) of the Restraint:

Another key requirement for granting habeas corpus is that the restraint must be "markedly illegal" (Habeas Corpus Act Art. 2(1), Habeas Corpus Rules Art. 4).

- Supreme Court's Rule for Post-Hague Return Order Cases: In a habeas corpus petition for the release of a child abducted to Japan, if a final Return Order under the Implementing Act has been issued against the custodian, and that custodian continues to hold the child in defiance of that order, then the custodian's ongoing restraint of the child possesses marked illegality. This holds true unless there are special circumstances making it "grossly unjust" (著しく不当 - ichijirushiku futō) to release the child from that custody for the purpose of return. (Such special circumstances might include, for example, a significant negative change in circumstances relevant to the child's return that has occurred after the Return Order became final, as per Article 117(1) of the Implementing Act).

- Application to Ms. Y's Restraint of C:

- Ms. Y was clearly continuing to exercise custody over C in defiance of the final Return Order, having resisted its direct enforcement.

- The Court found no circumstances suggesting it would be grossly unjust to release C from Ms. Y's custody to facilitate his return to the U.S.

- Therefore, Ms. Y's restraint of C was deemed to have marked illegality.

Outcome and Significance

Based on these findings—that C was under "restraint" and that this restraint was "markedly illegal"—the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision dismissing the habeas corpus petition and remanded the case. This strongly signaled that the petition should be granted, and indeed, on remand, the Nagoya High Court ordered C's release.

This decision is highly significant for several reasons:

- Habeas Corpus as an Enforcement Tool: It was the first published Supreme Court decision affirming that habeas corpus proceedings can be a viable, albeit supplementary, avenue for enforcing a child return order under the Hague Convention's Implementing Act when direct enforcement measures have been exhausted or proven ineffective.

- Defining "Restraint" for Influenced Children: The Court provided a nuanced interpretation of what constitutes "restraint" when a child with decisional capacity expresses a preference to stay with an abducting parent. The focus on the child's access to objective information and freedom from undue psychological influence sets a standard for assessing the genuineness of the child's "free will" in such coercive environments.

- "Marked Illegality" in Cases of Defiance: The ruling establishes a strong presumption that a parent's continued custody of a child in direct defiance of a final Hague Return Order constitutes "marked illegality," justifying habeas corpus relief unless exceptional circumstances make release grossly unjust.

- Supplementarity of Habeas Corpus: The commentary by Professor Oda accompanying the case suggests that the "supplementarity" requirement for habeas corpus (i.e., that no other suitable remedy is available) was likely deemed satisfied because the alternative enforcement mechanisms under the Implementing Act had already failed.

- Impact of Later Amendments to the Implementing Act: It is important to note that Japan's Implementing Act was amended in 2019 (effective 2020). These amendments were designed to strengthen the direct enforcement procedures for return orders (e.g., by not always requiring indirect enforcement first, and modifying rules about the child's presence during enforcement). Professor Oda suggests that if this case had occurred under the current, amended law, the initial direct enforcement might have been successful, potentially obviating the need for the subsequent habeas corpus proceedings.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 15, 2018, decision serves as a critical affirmation of the Japanese judiciary's commitment to upholding the spirit of the Hague Convention on International Child Abduction. By allowing habeas corpus as a potential remedy following the failure of direct enforcement, the Court provided an additional mechanism to address parental defiance of return orders. The judgment's careful consideration of the child's true "free will" in the coercive context of an abduction, and its strong stance on the illegality of defying a final court order, underscores the importance of judicial integrity and the ultimate aim of protecting the child's best interests as envisioned by the Convention.