Guilty of a Violation, but Not of Negligence? Japan's "Principle of Trust" in Traffic Accidents

Decision Date: October 13, 1967

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

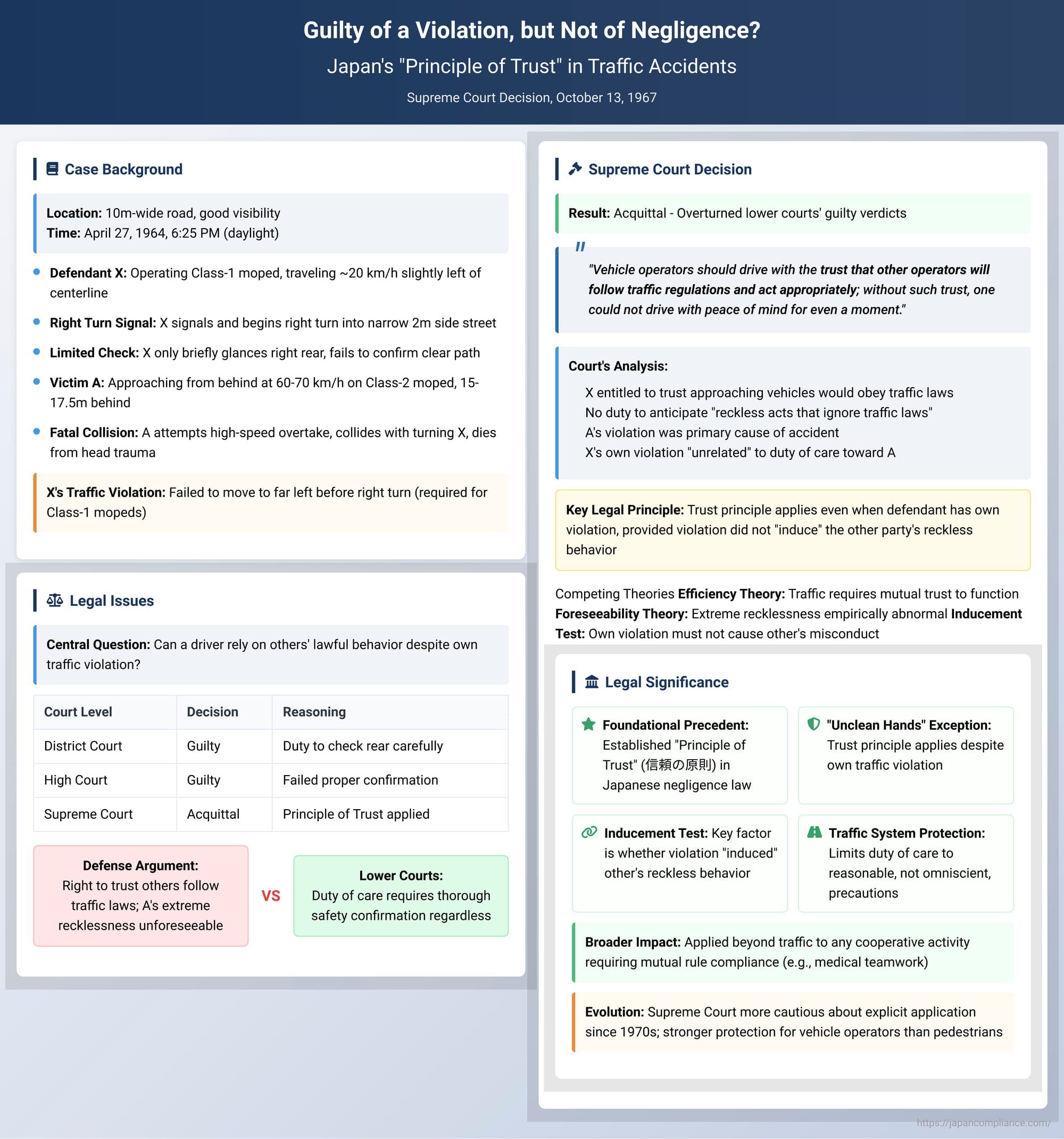

Determining fault in a traffic accident is rarely straightforward, especially when multiple parties have failed to follow the rules. But what happens when one driver's minor infraction is met with another's extreme recklessness? Can the first driver be held criminally negligent for the fatal consequences? A landmark 1967 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this very issue, establishing a vital legal doctrine known as the "Principle of Trust" (Shingai no Gensoku).

This case, involving a fatal collision between two mopeds, is remarkable because the Supreme Court acquitted a defendant who had committed a traffic violation himself. In doing so, it ruled that individuals have a right to assume that others on the road will act lawfully and are not required to anticipate every possible form of reckless behavior. This decision has had a profound impact on how negligence is assessed in Japan, not just in traffic accidents but in any cooperative activity where mutual reliance on rules is essential.

Factual Background

The incident occurred on the evening of April 27, 1964, at around 6:25 PM, when daylight still made headlights unnecessary. The defendant, X, was operating a Class-1 moped on a straight, 10-meter-wide road with good visibility and no other traffic.

X intended to make a right turn into a narrow 2-meter-wide side street. He was traveling at approximately 20 km/h slightly to the left of the centerline, signaling his intention to turn right. As he began the turn, he only briefly glanced to his right rear, failing to confirm that the way was completely clear.

At that same moment, the victim, A, was approaching from behind on a Class-2 moped at a very high speed of 60 to 70 km/h, intending to overtake X. A was about 15 to 17.5 meters behind X when X initiated his turn. Unaware of A's rapid approach, X proceeded with his turn, believing it was safe. He crossed the centerline and traveled about two meters diagonally when A's moped collided with his, causing A to fall. A subsequently died from head trauma and other injuries.

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court found X guilty of professional negligence resulting in death, reasoning that he had a duty to check his right rear carefully before turning. The defendant appealed this finding to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

In a pivotal judgment, the Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' verdicts and acquitted X. The Court's reasoning was grounded in a doctrine it explicitly articulated: the Principle of Trust.

The Court stated:

"Vehicle operators should drive with the trust that other operators will follow traffic regulations and act appropriately; without such trust, one could not drive with peace of mind for even a moment. ... Therefore, when considering the duty of care of a vehicle operator, this point must be given sufficient consideration. "

Applying this principle, the Court defined the limits of X's duty of care. As a driver signaling a right turn from near the centerline, X was entitled to trust that any vehicle approaching from behind would obey traffic laws—for example, by slowing down and waiting for him to complete his turn.

The Court concluded that X had no professional duty of care to anticipate a vehicle acting like A's—a vehicle that would "dare to violate traffic regulations, travel at a high speed, and even cross over to the right side of the centerline to overtake his own vehicle." The victim's actions were described as a "reckless act that ignored traffic laws" and the primary cause of the accident.

Most significantly, the Court addressed X's own traffic violation. At the time, the law required Class-1 mopeds to move to the far left of the road before making a right turn. X had failed to do this, instead turning from near the centerline. However, the Court declared that X's violation was "a matter unrelated to the existence or non-existence of the aforementioned duty of care" toward A.

Commentary and Analysis: Deconstructing the Principle of Trust

The 1967 decision is a cornerstone of Japanese negligence law, particularly for its application of the Principle of Trust even when the defendant himself was not acting perfectly.

The Justification for the Principle

The Supreme Court justified the principle on the grounds of promoting the efficiency and utility of high-speed transportation. If drivers had to constantly anticipate and guard against every conceivable illegal act by others, traffic would grind to a halt.

Legal scholarship offers a deeper justification. Rather than simply being a "clean hands" doctrine (where one must be blameless to benefit), the principle is best understood as a limit on foreseeability based on experience. In highly regulated activities like road traffic, it is empirically abnormal for another participant to act in a grossly negligent or reckless manner. Therefore, a person is not required to factor such abnormal, low-probability behavior into their own risk assessment. In this case, A's decision to overtake a turning vehicle at high speed by crossing the centerline was so exceptionally dangerous and contrary to norms that it fell outside the scope of what X needed to anticipate.

Trust with "Unclean Hands"

The most legally fascinating aspect of this case is that X was allowed to rely on the Principle of Trust despite his own violation of traffic law. This raises the question: why didn't his "unclean hands" disqualify him from the principle's protection?

The key concept is "inducement." An actor's own violation will typically negate the Principle of Trust only if that violation "induces" the other party's wrongful act. For example, if a driver suddenly swerves without signaling, inducing another driver to react erratically, they cannot then claim they trusted the other driver to act lawfully.

In this case, however, X's failure to move to the far left of the road could not be seen as having induced A's independent and reckless decision to overtake at extreme speed across the centerline. The two violations were legally and causally separate. The Supreme Court's decision to treat X's violation as "unrelated" to his duty of care towards A reflects this logic. A recent High Court decision similarly applied the principle to acquit a speeding driver who collided with a car that ran a red light, finding the defendant's speeding did not induce the victim's "reckless driving."

The Scope and Limits of the Principle

While foundational, the application of the Principle of Trust is not unlimited. Since the 1970s, the Supreme Court has become more cautious about explicitly applying it in traffic accident cases. The principle is most readily applied in vehicle-versus-vehicle scenarios, where all parties are licensed operators expected to know and follow a detailed set of rules. Courts are far more hesitant to apply it when the victim is a pedestrian, who is generally seen as less predictable.

Furthermore, the principle is not confined to road traffic. It has been applied in other contexts requiring professional cooperation and adherence to rules, such as team-based medical care.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1967 ruling in this case was a landmark moment for Japanese criminal law. It established that in a system of interdependent rules, individuals have a right to rely on the lawful behavior of others. Its most profound contribution was the clarification that one does not need to be perfectly compliant oneself to benefit from this trust, so long as one's own infraction does not cause or "induce" the far more egregious and reckless actions of another.

By doing so, the Court placed a reasonable limit on the scope of an individual's duty of care, preventing the law from demanding that citizens anticipate and guard against every possible—and even wildly improbable—form of recklessness from others. It is a principle that recognizes the necessity of mutual trust for the functioning of a complex, modern society.