Grave Flaws, No Excuses: Shareholder Resolutions and the Limits of Judicial Discretion in Japan

Case: Action for Confirmation of Nullity of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution (and alternative claim for cancellation)

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of March 18, 1971

Case Number: (O) No. 89 of 1969

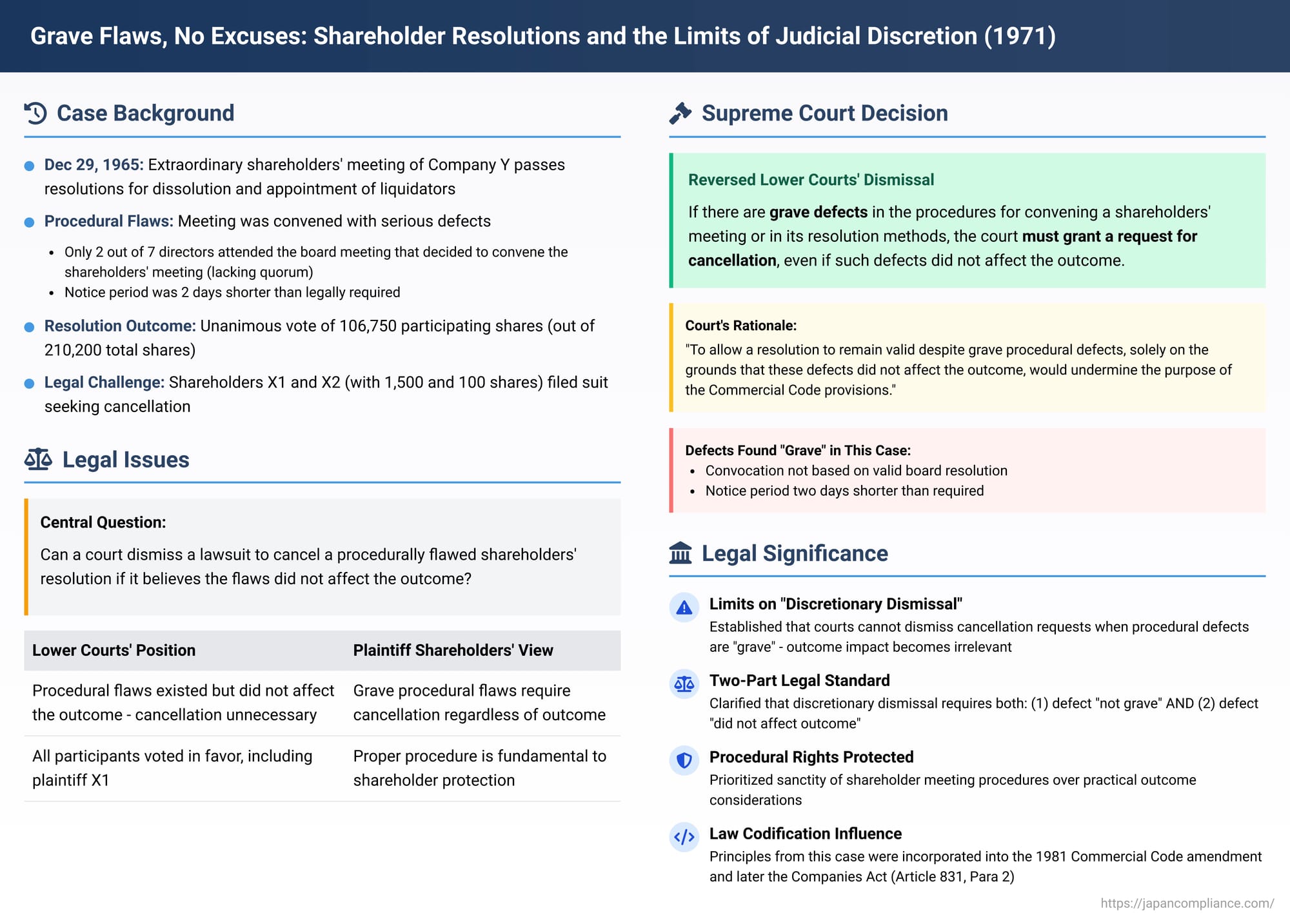

When shareholders challenge a company resolution due to procedural irregularities, can a court dismiss the challenge if it believes the flaws, however serious, didn't actually change the vote's outcome? A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on March 18, 1971, addressed this very question, establishing a crucial principle: if procedural defects in convening a shareholders' meeting or in its voting methods are "grave," the resolution must be cancelled, irrespective of its impact on the final result. This case significantly shaped the understanding of what's known as "discretionary dismissal" (裁量棄却 - sairyō kikyaku) in Japanese corporate law.

Facts of the Dissolution Resolution

The dispute involved Company Y. At an extraordinary shareholders' meeting held on December 29, 1965, resolutions were passed for the company's dissolution, and for the appointment of an auditor and statutory liquidators. These significant decisions were reportedly made by a unanimous vote of the 106,750 shares that participated in the resolution, out of a total of 210,200 issued shares.

However, two shareholders, X1 (N) and X2, filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of these resolutions, citing critical procedural flaws:

- Invalid Board Resolution for Convocation: The shareholders' meeting was convened based on a resolution passed by Company Y's board of directors. However, this board meeting itself was invalid because only two out of seven directors attended, thus lacking the necessary quorum for a valid decision.

- Insufficient Notice Period: The notice period for convening the extraordinary shareholders' meeting was two days shorter than the legally mandated period.

The Lower Courts' Stance: Outcome Over Process?

The court of first instance (Akita District Court, judgment dated October 9, 1967) and the appellate court (Sendai High Court, Akita Branch, judgment dated October 21, 1968) both acknowledged the existence of these procedural defects. They agreed that the board resolution authorizing the meeting was invalid and that the notice period was indeed insufficient.

Despite these findings, both lower courts dismissed the plaintiffs' request to cancel the resolutions. Their reasoning centered on the perceived lack of impact these flaws had on the ultimate outcome:

- They noted that all shareholders, including one of the plaintiffs (X1), were reportedly aware that Company Y was in a dire financial situation where dissolution was almost inevitable.

- The resolutions for dissolution and the appointment of officials were passed unanimously by all shareholders who actually participated in the voting, a group that included X1.

- Furthermore, three of the five directors who had been absent from the inquorate board meeting subsequently gave their approval to the decision to convene the shareholder meeting.

- The challenge to the resolutions came from only two shareholders, X1 (holding 1,500 shares) and X2 (holding 100 shares), a small fraction of the total.

Based on these factors, the lower courts concluded that the procedural flaws in convening the shareholders' meeting "clearly did not affect the outcome of the resolutions." Therefore, they declined to cancel them. X1 and X2 appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Reversal: Prioritizing Procedural Sanctity

The Supreme Court took a significantly different view. It partially quashed the High Court's decision and, in a self-pronounced judgment, cancelled the shareholder resolutions concerning the company's dissolution and the appointment of the auditor and statutory liquidators (this was the plaintiffs' alternative claim, their primary claim for nullity confirmation being handled separately).

The Supreme Court's reasoning was clear and direct:

"If there are grave defects (重大な瑕疵 - jūdai na kashi), considering their nature and extent, in the procedures for convening a shareholders' meeting or in its resolution methods, the court must grant a request for cancellation of the resolution, even if such defects are found not to have affected the outcome of the resolution. Dismissing such a request is not permissible."

The Court elaborated on this fundamental principle:

"To allow a resolution to remain valid despite grave procedural defects, solely on the grounds that these defects did not affect the outcome, would undermine the purpose of the Commercial Code provisions. These provisions strictly regulate the procedures for convening shareholders' meetings and the methods of resolution to ensure the proper operation of shareholders' meetings and thereby protect the interests of both the shareholders and the company."

Applying this to the specifics of Company Y's meeting, the Supreme Court found:

The procedure for convening the shareholders' meeting in question suffered from defects "that must be described as grave in nature and extent." These were:

- The convocation was not based on a valid resolution of the board of directors, the body authorized to make such a decision.

- The notice of convocation was dispatched to all shareholders only twelve days before the meeting date, which was two days short of the statutory requirement.

Therefore, the Court concluded:

"Even if, as the High Court found and indicated, these defects did not influence the outcome of the respective resolutions, it is not permissible to dismiss the appellants' alternative claim seeking cancellation of these resolutions due to these defects, solely on that basis." The High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of the law.

Analysis and Implications: Discretionary Dismissal and "Grave Defects"

This 1971 Supreme Court judgment is a cornerstone in understanding how Japanese courts handle challenges to shareholder resolutions marred by procedural flaws. It particularly illuminates the boundaries of "discretionary dismissal" (sairyō kikyaku).

The Concept of "Discretionary Dismissal"

Under Japanese company law (currently Article 831, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act, which evolved from earlier Commercial Code provisions), a court has the authority to dismiss a shareholder's request to cancel a resolution, even if a procedural violation is found. This is permissible if two conditions are cumulatively met:

- The violation of laws or the articles of incorporation in the convocation procedure or resolution method is "not material" (or "not grave" - 重大でなく - jūdai de naku).

- It is recognized that the violation "did not affect the resolution" (決議に影響を及ぼさない - ketsugi ni eikyō o oyobosanai).

The history of this provision is informative. An earlier version in the pre-1950 Commercial Code was seen as granting overly broad discretion to courts and was repealed. It was later reinstated in 1981 (in the Commercial Code) in a much stricter form, largely reflecting the principles articulated in this 1971 Supreme Court decision, and this stricter approach has been carried into the current Companies Act. The current interpretation is that this isn't about giving courts wide-ranging policy-making power but rather a rule to be applied when both specific conditions (non-gravity and no effect on outcome) are demonstrably met.

What Constitutes a "Grave Defect"?

The 1971 Supreme Court ruling is pivotal because it establishes a clear hierarchy: if a procedural defect is determined to be "grave," the second condition (whether it affected the outcome) becomes irrelevant for the purpose of discretionary dismissal. The court cannot dismiss the cancellation request; it must cancel the resolution.

The "gravity" of a defect is generally assessed by considering whether the shareholder interests intended to be protected by the violated legal rule or article of incorporation have been infringed. The prevailing academic view is that only truly trivial or minor defects—where challenging them might even seem like an abuse of rights—would be considered "not grave."

The Supreme Court, in this 1971 case and others, has shown a tendency to be cautious about deeming defects "non-grave." It often looks to the general, abstract purpose of the violated legal provision. In this instance, the failure to obtain a valid board resolution for convening the meeting and the provision of insufficient notice were collectively deemed "grave."

This sometimes contrasts with trends in lower court decisions. Some lower courts have been more willing to find defects "non-grave," particularly if they perceive no substantial harm to shareholder rights or if the defect seems to have been "cured" by other circumstances. For example, in some cases involving closely-held companies, very high shareholder attendance despite improper notice has occasionally led to a finding that the defect was not grave. However, it's important to note that certain defects, such as convening a meeting without any valid board resolution at all, might be considered so fundamental that they cannot be cured even by full shareholder attendance.

The "No Effect on Resolution" Requirement

For a court to exercise discretionary dismissal, it must also be found that the defect "did not affect the resolution." Proving this can depend heavily on the nature of the flaw:

- Flaws akin to vote miscounts: If the defect involves issues like the casting of votes by ineligible persons or errors in vote tallying, the "no effect" condition can often be demonstrated relatively clearly. If, after excluding the improperly cast votes or correcting the tally, the resolution would still have passed by the required majority, then the defect did not affect the outcome. In such cases, discretionary dismissal is possible, provided the flaw is also deemed "not material" (though often, the non-materiality aspect is less contentious in pure vote-counting errors if the outcome is mathematically unaffected).

- Flaws in general meeting procedures (convocation to voting process): For defects such as improper notice, denial of speaking rights, or issues with the meeting's conduct, proving a definitive lack of impact on the resolution's outcome is much more challenging. The traditional majority academic view was that it is almost impossible to strictly prove that such a procedural flaw had no causal connection to how shareholders voted or to the resolution itself. This made discretionary dismissal for such flaws very difficult.

The 1971 Supreme Court judgment, by focusing on the "gravity" of the convocation defects, sidestepped a deep dive into whether those grave defects actually affected the outcome for the purpose of deciding whether to cancel. Its stance was: grave defects mean cancellation, period.

However, legal commentary and the evolution of the law suggest that for non-grave procedural flaws, discretionary dismissal is not entirely impossible even if strict mathematical proof of "no effect" is elusive. If there's a strong probability of no impact on the outcome (perhaps evident in closely-held companies where shareholder intentions are very clear beforehand) and the flaw is genuinely minor, dismissal might be considered. In practice, when courts do dismiss cancellation requests for procedural flaws deemed minor, they may not always demand absolute, rigorous proof of "no effect."

Relationship Between the Two Requirements: "Grave Defect" and "No Effect"

Article 831, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act clearly mandates that for discretionary dismissal, the defect must be both "not material" (not grave) and have "not affected the resolution."

The 1971 Supreme Court decision highlights the pre-eminence of the "gravity" assessment.

- If a defect is grave: The resolution must be cancelled. The question of whether it affected the outcome is not a basis for upholding the resolution.

- If a defect is not grave: Then, the court proceeds to the second question: did it affect the outcome? If it did not affect the outcome, then discretionary dismissal is possible. If it did affect the outcome (or if it's unclear/unproven that it didn't), then even a non-grave defect could lead to cancellation.

The commentary suggests that for flaws analogous to vote miscounts, the "no effect" criterion often becomes the decisive factor in practice (assuming the error itself isn't so vast as to be inherently "grave"). For other procedural flaws concerning the conduct of the meeting, both criteria are sequentially relevant.

A point of academic discussion, hinted at by the structure of the 1971 judgment, is the theoretical possibility of a defect being "grave" yet demonstrably having "no effect on the outcome." The Supreme Court's ruling implies that even in such a rare scenario, cancellation would be required to uphold the integrity of corporate procedures. In reality, it's often the case that if a defect is truly grave, it's difficult to confidently assert it had no influence whatsoever; conversely, if it clearly had no effect, it's often because the flaw was minor to begin with.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 18, 1971, judgment serves as a critical legal precedent that sharply defines the limits of judicial discretion when faced with procedurally flawed shareholder resolutions. It sends a strong message that the formal requirements for convening and conducting shareholder meetings are not mere technicalities that can be easily overlooked if the "right" outcome is achieved. When procedural defects are "grave" in nature and degree—such as holding a meeting based on an invalid board decision or with significantly deficient notice—the law demands accountability through cancellation of the resolution. This prioritizes the overarching legislative intent to ensure fair and proper corporate governance, protecting the collective interests of shareholders and the company itself, even if, in a particular instance, the flaws might not have swayed the vote. While minor defects that don't impact the result might be excused, grave breaches of procedure are, in essence, fatal to the resolution's validity.