Good Faith in Taxation: Japan's Supreme Court on the "Blue Form" System and Taxpayer Reliance

Judgment Date: October 30, 1987

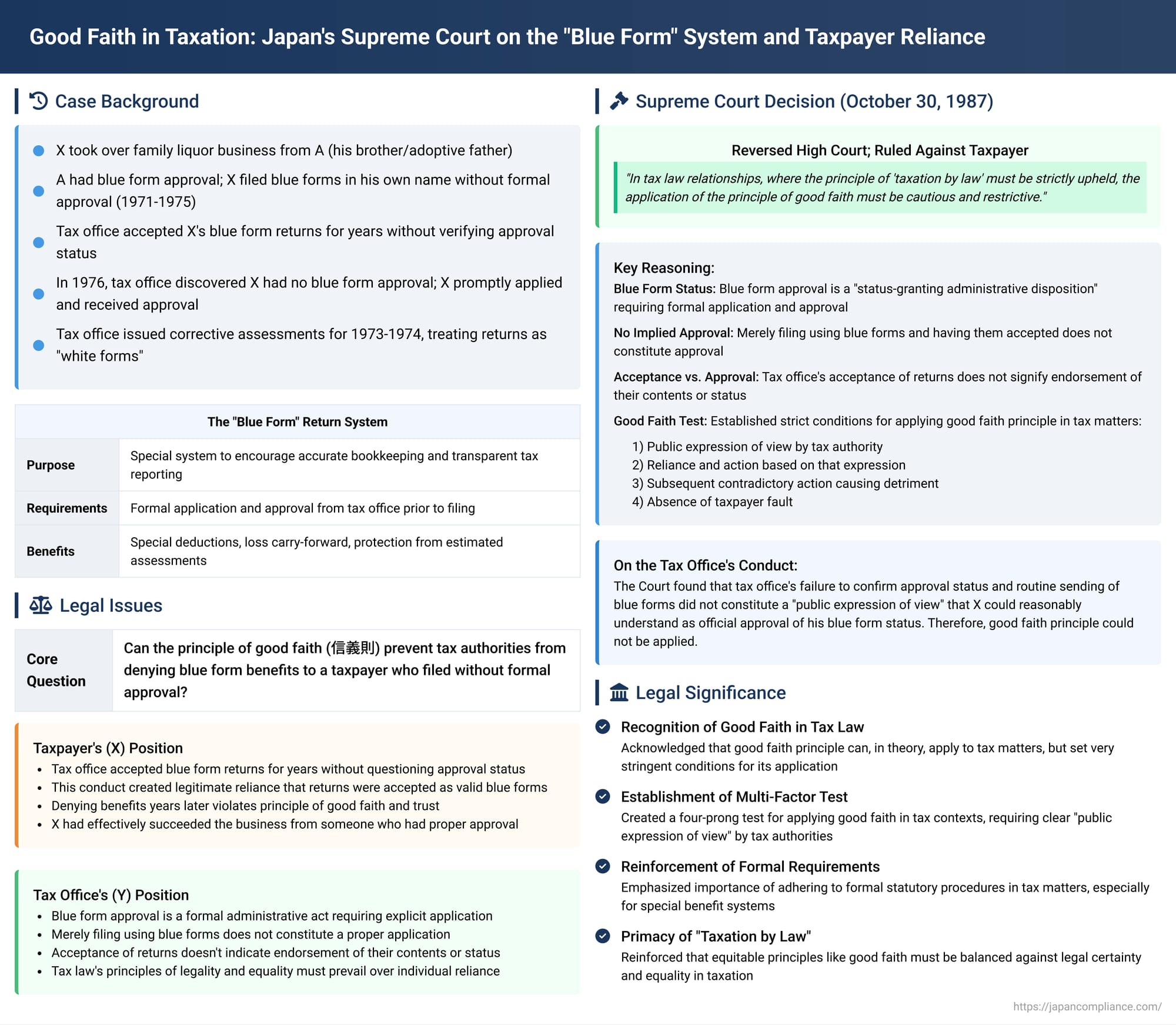

In a landmark decision with profound implications for the application of general legal principles in tax law, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed whether a taxpayer could invoke the principle of good faith and trust (shingisoku - 信義則) to prevent the tax authorities from denying the benefits of the "blue form tax return" system, even when the taxpayer had not formally obtained the required approval. While acknowledging that the principle of good faith could apply in tax matters under exceptional circumstances, the Court ultimately found that such circumstances were not present in this specific case, thereby underscoring the formal requirements of the blue form system and the strict conditions for invoking good faith against tax assessments.

Background: The "Blue Form" and a Family Business

The case involved X (plaintiff/respondent on appeal), who had taken over a family liquor sales business, "S Liquors" (a fictionalized name for B Shoten). The business was originally run by A, who was both X's biological elder brother and adoptive father. A had obtained approval from the tax office to file "blue form" tax returns (aoiro shinkoku - 青色申告) for the business income.

The blue form tax return system in Japan is a special scheme designed to encourage accurate bookkeeping and transparent tax reporting. Taxpayers who apply for and receive approval from the tax office to use this system are granted various tax advantages. These benefits can include special deductions, the ability to carry forward net operating losses, and protection from purely estimated tax assessments. Obtaining this approval is a formal administrative act that confers a specific legal status upon the taxpayer.

X had previously worked at the Moji Tax Office before joining S Liquors. By around November 1954, X had effectively become the primary individual running the business. From 1954 through 1970, the blue form tax returns for S Liquors were filed in A's name, as A was the one with the official blue form approval.

The critical events unfolded as follows:

- X Files in His Own Name (1971 Tax Year): In March 1972, for the 1971 tax year, X filed a final income tax return for the business using a blue form, but this time in his own name. Crucially, X had not applied for or received his own blue form approval from the tax office.

- Tax Office Acceptance: The relevant tax office chief, Y (defendant/appellant), accepted X's 1971 blue form return without verifying whether X personally held blue form approval.

- Continued Acceptance (1972-1975 Tax Years): For the subsequent tax years from 1972 through 1975, Y's office continued to send blue form tax return papers to X. X used these forms to file his final returns, which the tax office accepted, and X paid the income tax amounts declared on these returns.

- Death of A: X's adoptive father, A, passed away on September 21, 1972.

- Discovery and Formal Approval (1976): In March 1976, Y's office pointed out to X that he had never formally applied for blue form approval in his own name. Upon being notified, X immediately submitted an application and was granted blue form approval for the 1976 tax year and subsequent years.

- Corrective Assessments: Following this, Y issued corrective income tax assessments and underpayment penalties for X's 1973 and 1974 tax years. These corrective actions were based on denying the validity of X's blue form filings for those years and instead treating them as standard "white form" returns, which do not offer the same tax advantages.

X challenged these corrective assessments, arguing that the tax office's actions violated the principle of good faith and trust, given their prior acceptance of his blue form filings.

The Lower Courts' Rulings

The Fukuoka District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of X, finding that the tax office's conduct was contrary to the principle of good faith.

The Fukuoka High Court (appellate court) upheld this decision. It reasoned that although X had not formally applied for blue form approval in his own name, Y (the tax office chief) had accepted his blue form returns for several years and had failed to confirm his approval status. The High Court concluded that for Y to now deny the validity of those blue form filings solely on the grounds of X's lack of initial application, after such a period of acceptance, was a breach of the principle of good faith and trust and therefore impermissible. The corrective assessments were deemed illegal.

The Tax Office Chief, Y, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Strict Conditions for Good Faith in Tax Law

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision, ultimately ruling against X. The Court's judgment provided a detailed exposition on the nature of the blue form system and, more broadly, on the stringent conditions under which the principle of good faith and trust could be applied in tax law.

The Formal Nature of Blue Form Approval

The Court first emphasized the specific legal character of the blue form approval:

- Status-Granting Disposition: Blue form approval is a "status-granting administrative disposition" (sekken-teki shobun - 設権的処分). It confers a distinct legal status or qualification upon the taxpayer, allowing them to file returns using the special blue forms and thereby access various procedural and substantive tax advantages (tax privileges).

- No Implied Approval: Given this formal system, the Court stated that even if a taxpayer (like X) had been involved in a business run by a predecessor (like A) who held blue form approval, and even if X inherited or continued that business, if X themselves did not submit an application and receive the tax office chief's approval in their own name, then any blue form tax return filed by X could not be recognized as having the efficacy of a true blue form filing.

- Error of Lower Court: The Supreme Court found that the High Court's reasoning—suggesting that there could be exceptional cases where blue form status is recognized even without formal approval—was an erroneous interpretation of the laws governing the blue form system.

- X's Status for 1973-1974: Since it was established that X had not received blue form approval for the 1973 and 1974 tax years, his returns for those years could not be treated as blue form returns and should, in principle, be handled as standard "white form" returns. The next question, therefore, was whether any special circumstances existed that would render the corrective assessments (based on this white form status) illegal.

The Principle of Good Faith and Trust (Shingisoku) in Tax Law

This was the core of the Supreme Court's constitutional and general legal principle analysis:

- Potential Applicability: The Court began by acknowledging a crucial point: "Even for a tax assessment that conforms to tax statutes, there might be cases where applying the general legal principle of good faith and trust could lead to the said tax assessment being cancelled as illegal." This was a significant affirmation that shingisoku is not entirely alien to the realm of tax law.

- Cautious Application Required: However, the Court immediately followed this with a strong caveat: "In tax law relationships, where the principle of 'administration by law,' and especially the principle of 'taxation by law' (sozei hōritsu shugi - 租税法律主義), must be strictly upheld, the application of the said legal principle [of good faith] must be cautious and restrictive."

- Exceptional Circumstances Needed: The application of the good faith principle to override a legally sound tax assessment should only be considered: "...when such special circumstances exist that protecting the taxpayer's reliance by waiving the tax assessment related to the said taxation, even at the sacrifice of the requirements of equality and fairness among taxpayers in the application of tax laws, is necessary to the extent that not doing so would be contrary to justice." This sets an extremely high bar.

- Indispensable Conditions for "Special Circumstances": The Supreme Court then laid out a multi-factor test to determine if such "special circumstances" exist. It stated that consideration of the following points is indispensable:

- Public Expression of View: Whether the tax authority made a "public expression of its view" (kōteki kenkai no hyōji - 公的見解の表示) to the taxpayer, which became the specific object of the taxpayer's reliance.

- Taxpayer Reliance and Action: Whether the taxpayer relied on that specific expression and acted based on that reliance.

- Contradictory Subsequent Action and Detriment: Whether a subsequent tax assessment was made that contradicted the tax authority's earlier expression, and whether this contradiction caused the taxpayer to suffer economic detriment.

- Absence of Taxpayer Fault: Whether the taxpayer was not at fault (or blameworthy - seme ni kisu beki jiyū ga nai - 責めに帰すべき事由がない) for relying on the tax authority's expression and acting upon it.

Application of the Good Faith Test to X's Case

The Supreme Court then applied these stringent conditions to the facts involving X:

- Acceptance of Returns is Not Endorsement: The Court noted that under Japanese tax law, the submission of a tax return by a taxpayer completes the act of declaration. The tax office chief's subsequent "acceptance" of the return and "collection" of the declared tax amount do not, in any way, signify an endorsement or approval of the contents of that return. (Referencing Article 24 of the Act on General Rules for National Taxes).

- Filing Blue Form is Not Application for Approval: It is self-evident, the Court stated, that a taxpayer merely filing a tax return using a blue form cannot be construed as having thereby applied for blue form approval.

- Tax Office Actions Did Not Constitute "Public Expression of View": The Court found that the tax office chief's failure to confirm X's blue form approval status when X first filed in his own name, and the subsequent act of sending blue form papers to X for the following years, did not clearly constitute an act by which X could reasonably understand that his submission of blue forms had been officially approved by the tax office chief.

- No Contradiction of a Prior "Public View": Consequently, the corrective assessments issued by Y (treating the 1973 and 1974 returns as white forms) could not be said to be assessments that contradicted a "public expression of view" previously given by Y to X.

- No Room for Good Faith Application: Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded, there was no room to even consider applying the principle of good faith and trust to the corrective assessments in this case.

Judgment: Reversal and Remand

The Supreme Court found that the High Court's judgment, which had deemed the corrective assessments illegal based on the principle of good faith, was flawed due to an erroneous interpretation and application of the law, leading to an incomplete examination of the case. The Supreme Court therefore reversed the portion of the High Court's judgment that had ruled in favor of X. The case was remanded to the Fukuoka High Court for further proceedings consistent with the Supreme Court's opinion—essentially, to re-evaluate the case on the premise that X's 1973 and 1974 returns should be treated as white form returns, unless other specific legal arguments regarding the calculation of the tax itself were to be considered.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

This 1987 Supreme Court decision is a landmark in Japanese tax jurisprudence for several key reasons:

- Conditional Applicability of Good Faith in Tax Law: It formally acknowledged that the general legal principle of good faith and trust can, in theory, be applied to invalidate a tax assessment. This was a significant step, as tax law is often seen as a domain where strict statutory adherence (taxation by law) is paramount.

- Establishment of a Strict Test: More importantly, the decision established a stringent, multi-pronged test for invoking the good faith principle in tax cases. This test, requiring a clear "public expression of view" by tax authorities, justifiable taxpayer reliance, subsequent contradictory action causing detriment, and an absence of taxpayer fault, sets a very high threshold.

- Reinforcement of Formal Requirements: The ruling strongly reinforces the importance of adhering to formal statutory procedures in tax matters, particularly for systems like the blue form tax return which confer special benefits. Mere administrative oversight or acceptance of incorrect filings by the tax office does not easily give rise to protected reliance interests for the taxpayer if the taxpayer has not fulfilled their own procedural obligations (like applying for approval).

- Primacy of "Taxation by Law": The decision underscores that the principle of "taxation by law" is the dominant consideration. The application of equitable principles like good faith is exceptional and must be carefully circumscribed to avoid undermining legal certainty and equality in taxation.

- Guidance for Taxpayer-Authority Interactions: The case provides implicit guidance: taxpayers cannot generally rely on informal actions or prolonged inaction by tax authorities as a substitute for formal approvals or as a basis for assuming a particular tax treatment is officially sanctioned. For a reliance interest to be protected under the good faith principle, there usually needs to be a more concrete and official representation by the tax authority.

This judgment has since been a leading case in discussions about the role of good faith and estoppel-like principles in Japanese tax administration, frequently cited when taxpayers attempt to challenge assessments based on alleged prior inconsistent conduct or representations by tax officials. It highlights the careful balance the Japanese legal system seeks to strike between ensuring administrative fairness to individual taxpayers and upholding the integrity and uniformity of the tax system as mandated by law.