Golf Club Memberships in Bankruptcy: Japanese Supreme Court Curbs Trustee's Termination Power

Case ① Judgment Date: February 29, 2000

Case Name (①): Claim for Refund of Membership Deposit

Court (①): Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case ② Judgment Date: March 9, 2000

Case Name (②): Claim for Refund of Membership Deposit, etc.

Court (②): Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

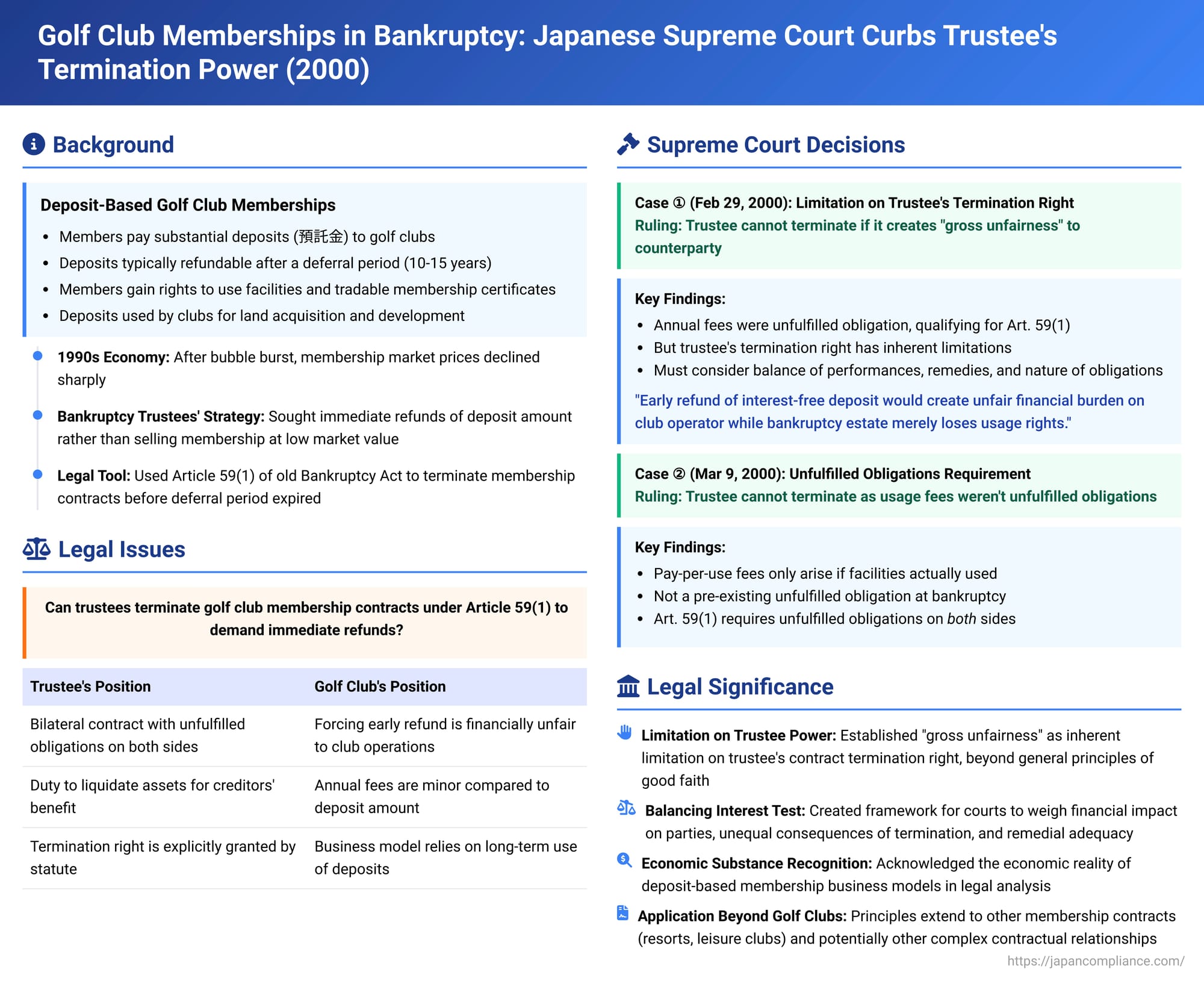

In early 2000, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered two significant rulings (hereinafter Case ① and Case ②) that profoundly impacted the treatment of deposit-based golf club memberships when a member declares bankruptcy. These decisions addressed whether a bankruptcy trustee could terminate such membership contracts to demand an immediate refund of the substantial membership deposit, particularly when the contractual deferral period for the refund had not yet expired.

Background: Deposit-Based Golf Club Memberships

Deposit-based membership (預託金会員制 - yotakukin kaiinsei) is a common operational model for golf clubs in Japan. Prospective members pay a significant sum of money (referred to generally as a "deposit") to the club operating company. This payment grants them membership status and rights to use the golf course facilities. The collected deposits serve as a crucial source of funding for the operating company, often used for land acquisition and facility development, typically held interest-free for a specified period (a deferral period - 据置期間 sueoki kikan). After this period, the deposit is usually refundable upon the member's withdrawal.

These memberships (会員権 - kaiinken) often possess considerable financial value and are themselves tradable assets. Consequently, when a member goes bankrupt, their membership rights fall under the administration of the bankruptcy trustee. While one method of realizing the asset's value is selling it on the market, market prices for such memberships had slumped after Japan's economic bubble burst. Thus, trustees often preferred to seek a refund of the deposit directly from the club operator. The crux of the issue in the cases discussed here was that the contractual deferral period for the deposit refund had not yet passed, preventing a straightforward claim based on withdrawal rules. To overcome this, the bankruptcy trustees sought to use Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the old Bankruptcy Act (equivalent to current Article 53, Paragraph 1), which grants trustees the power to terminate bilateral executory contracts, thereby hoping to trigger an immediate refund of the deposit as a form of restitution.

The Supreme Court, in both Case ① and Case ②, denied the bankruptcy trustee's right to terminate the membership contracts. These outcomes were noteworthy as they differed from some prevailing academic opinions and earlier lower court rulings, carrying significant practical and theoretical weight.

Case ①: Supreme Court Judgment of February 29, 2000

Facts of Case ①

Y, the defendant (appellant to the Supreme Court), operated a deposit-based golf club. To acquire membership, individuals had to pay an initiation deposit and a name registration fee. Members were entitled to use the golf course and participate in club-sponsored competitions, while also being obligated to adhere to club rules, board decisions, and pay annual fees and golf course usage fees. Y was obliged to refund the initiation deposit upon loss of membership status, but if this occurred within 10 years of joining, the refund was due only after 10 years had passed from the joining date.

In February 1990, company A paid Y an initiation deposit of 23 million yen and became a member (the "Membership Contract"). In October of the following year, A was declared bankrupt. X, appointed as A's bankruptcy trustee (plaintiff, respondent before the Supreme Court), notified Y of the termination of the Membership Contract pursuant to Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the old Bankruptcy Act and demanded the refund of the initiation deposit.

Supreme Court's Ruling in Case ①

The Supreme Court overturned the lower court decisions that had favored the trustee and ultimately dismissed X's claim.

- Nature of the Membership Contract:

The Court characterized the deposit-based golf club membership contract as a bilateral agreement where the payment of the deposit and the acquisition of golf course facility usage rights are the primary reciprocal considerations. If members also have an obligation to pay annual fees, this payment also forms part of the reciprocal relationship. When a member with an annual fee obligation becomes bankrupt, the golf club operator's duty to maintain the facilities in a usable state and allow member access, and the member's duty to pay annual fees, can be considered mutually unfulfilled obligations under Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the old Bankruptcy Act. - Limitation on the Trustee's Termination Right:

The Court explained that Article 59, Paragraph 1, which allows a bankruptcy trustee to terminate a contract if both parties have unfulfilled obligations at the time of bankruptcy declaration, is intended to ensure fairness between the contracting parties and to facilitate the swift conclusion of bankruptcy proceedings. Consequently, even if mutual unfulfilled obligations exist, if terminating the contract would result in a "grossly unfair situation" (著しく不公平な状況 - ichijirushiku fukōhei na jōkyō) for the counterparty, the trustee cannot exercise this termination right. This limitation is considered an inherent constraint within Article 59, Paragraph 1 itself, rather than one derived from general principles like good faith or abuse of rights. - Assessing "Gross Unfairness":

Whether a grossly unfair situation arises is to be determined by comprehensively considering various factors. These include:- The balance of the performances that each party would have to render as restitution upon termination.

- The extent to which the counterparty's disadvantage can be remedied by provisions such as Article 60 of the old Bankruptcy Act (which deals with claims arising from termination).

- Whether the bankrupt party's unfulfilled obligations are fundamental and core to the bilateral contract or merely incidental.

The commentary notes that concepts like "disadvantage," "recovery," and "essential/core nature" are subject to interpretation and these criteria are not unequivocally clear, posing a challenge for future predictability.

- Application to the Golf Club Membership Contract:

- Economic Reality of Deposits: The Court acknowledged the economic reality that the development of golf club facilities is typically made possible by raising funds from numerous members, free of interest burdens. The deposit is intended for this facility development and is expected to be refunded only after a certain period. Forcing an immediate full refund upon a member's bankruptcy, while the club must continue maintaining facilities for other members, imposes a significant, unplanned financial burden on the club operator. This burden is particularly severe for clubs where memberships are difficult to sell on the market.

- Imbalance of Consequences: On the other hand, the bankrupt estate merely loses the right to use the golf facilities and incurs no particular financial outlay due to the termination. This creates a stark imbalance.

- Inadequacy of Damages Claim: It would generally be difficult for the golf club operator to recover this significant disadvantage by filing a damages claim as a bankruptcy claim under Article 60 of the old Bankruptcy Act.

- Nature of Annual Fees: Even when annual fees are required, they are typically very small compared to the deposit amount and are considered incidental, not a core or essential part of the membership contract. Some clubs do not even charge annual fees, a publicly known fact.

- Unjust Enrichment Concerns: If the market value of the golf membership is lower than the deposit amount, allowing the trustee to use Article 59, Paragraph 1 termination to claim a full immediate refund of the deposit in exchange for forfeiting a less valuable membership right would affirm a grossly unfair outcome.

- Alternative for Trustee: If the trustee's goal is to prevent the depletion of the bankrupt estate by avoiding future annual fee payments, this can be achieved by following the club's prescribed procedures for withdrawal, rather than resorting to contract termination under Article 59, Paragraph 1.

- Conclusion in Case ①:

Considering these factors, the Court concluded that if trustee X were allowed to terminate the Membership Contract, it would create a grossly unfair situation for the club operator Y. Therefore, X could not terminate the Membership Contract under Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the old Bankruptcy Act.

Case ②: Supreme Court Judgment of March 9, 2000

Facts of Case ②

Y operated a deposit-based golf club. Prospective members acquired membership by paying a deposit and an initiation fee. Members had priority rights to use the club facilities and were obligated to pay facility usage fees when they played, but there were no annual fee obligations. Y was obligated to refund the deposit upon a member's withdrawal, but only after 15 years had passed since enrollment.

In August 1988, B paid a deposit of 6.5 million yen and an initiation fee of 1.5 million yen to become a member. B was declared bankrupt in June 1996. X, appointed as B's bankruptcy trustee, notified Y of the termination of the membership contract under Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the old Bankruptcy Act and demanded the refund of the deposit.

Supreme Court's Ruling in Case ②

The Supreme Court, as in Case ①, overturned the lower court decisions and dismissed X's claim.

- Member's Unfulfilled Obligations:

The Court stated that the obligation to pay facility usage fees only arises if the member actually uses the facilities. Therefore, it was clear that this could not be considered an unfulfilled obligation of the member at the time of the bankruptcy declaration. The High Court's contrary finding that these pay-per-use fees constituted unfulfilled obligations was overturned. - Conclusion in Case ②:

While the membership contract was a bilateral agreement with the deposit payment and the club's obligation to allow facility use being reciprocal, and Y's (the club's) obligation was unfulfilled at the time of bankruptcy, there were no unfulfilled obligations on the part of the bankrupt member B. Consequently, the requirements of Article 59, Paragraph 1 (that both parties have unfulfilled obligations) were not met. Therefore, trustee X could not terminate the membership contract under this provision. The Court reached this conclusion without needing to engage in the "gross unfairness" analysis applied in Case ①.

Significance and Impact of the Rulings

These two Supreme Court decisions have had a substantial impact on bankruptcy practice concerning deposit-based memberships:

- Establishment of "Gross Unfairness" Limitation: Case ① was groundbreaking in establishing that the trustee's termination right under Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the old Bankruptcy Act is not absolute and can be restricted if it leads to "gross unfairness" for the counterparty.

- Clarification on "Unfulfilled Obligations": Case ② clarified that for Article 59, Paragraph 1 to apply, there must be substantive, ongoing unfulfilled obligations on the part of the bankrupt. Contingent obligations like pay-per-use fees do not qualify.

- Solidification of Practice: These rulings effectively established a clear direction in bankruptcy practice: bankruptcy trustees generally cannot terminate deposit-based golf club membership contracts solely to secure an early refund of the deposit if doing so would be grossly unfair to the club operator, or if the bankrupt member lacks genuine unfulfilled contractual obligations (like annual fees). Indeed, another Supreme Court judgment on March 9, 2000 (separate from Case ② here but concerning a similar issue) also denied a trustee's termination right using language almost identical to that in Case ①.

Future Implications

The principles articulated in these golf club membership cases, particularly the "gross unfairness" doctrine, are likely to be invoked in disputes involving other types of membership contracts (e.g., resort clubs, leisure clubs) and various other non-typical or evolving contractual relationships in bankruptcy proceedings. The precise circumstances under which this limiting principle will apply and what specific individual factors will be weighed remain to be seen, and further clarification will depend on the accumulation of future court decisions.

In essence, these twin Supreme Court judgments significantly refined the application of general bankruptcy contract termination rules, offering a degree of protection to businesses operating membership schemes against untimely and financially disruptive demands arising from member bankruptcies, while also carefully considering the underlying obligations of the parties involved.