Golf Club Memberships & Corporate Spin-offs: Japanese Supreme Court on Successor Company Liability for Deposits

Date of Judgment: June 10, 2008

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

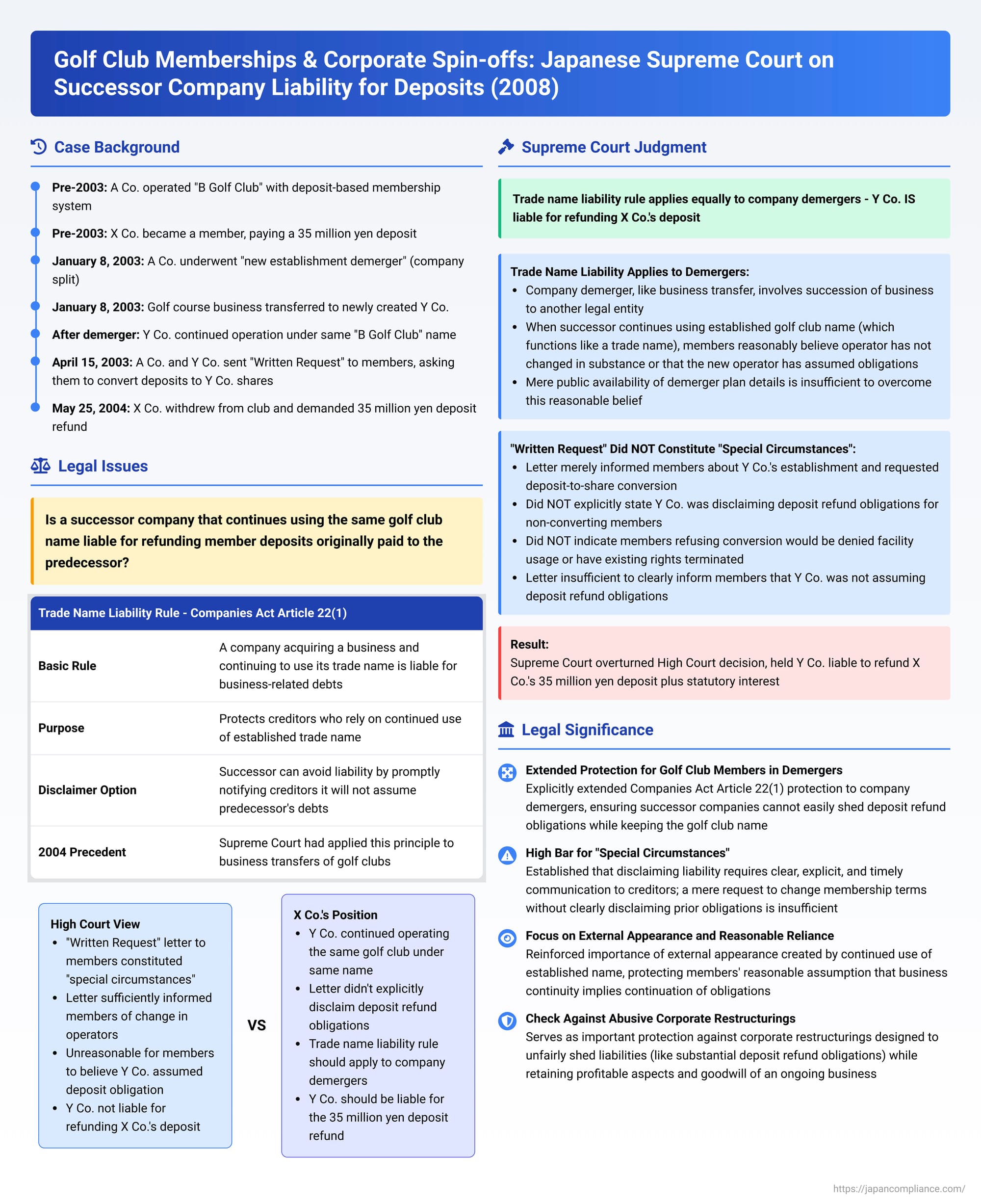

Deposit-based golf club memberships have long been a feature of the leisure industry in Japan. Members typically pay a substantial upfront deposit to the club operator in exchange for the right to use the golf facilities, with the expectation that this deposit will be refunded upon withdrawal from the club. A complex legal issue arises when the company operating such a golf course undergoes a corporate restructuring, such as a "company demerger" (会社分割 - kaisha bunkatsu or spin-off), transferring the golf business to a new or different company. If the new company continues to operate the golf course under the same club name, is it liable for refunding the deposits originally paid to the previous operator?

This question, critical for protecting the financial interests of club members, was addressed by the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in its decision on June 10, 2008.

The Legal Principle: Liability of a Business Successor Continuing to Use the Same Trade Name

Japanese company law contains a provision (currently Article 22, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act, formerly Article 26, Paragraph 1 of the Commercial Code) that addresses the liability of a company that takes over a business and continues to use the trade name of the previous business operator.

- General Rule: If a company acquires a business from another entity and continues to use the trade name (or a name that is clearly identifiable with the previous business), it can also be held liable for the business-related debts incurred by the original operator.

- Purpose: This rule is designed to protect creditors who might reasonably rely on the continued use of the established trade name as an indication that the business operations (and the associated obligations) are continuing under the same, or a fully responsible successor, entity.

- Disclaimer: The successor company can avoid this liability if it promptly notifies creditors that it will not be assuming the predecessor's debts or if it registers a disclaimer to that effect alongside the registration of the trade name transfer.

A Key Precedent (2004 Supreme Court Decision): Prior to the 2008 case, the Supreme Court, in a decision from February 20, 2004, had already applied this principle by analogy to situations involving the outright business transfer (as opposed to a company demerger) of a deposit-based golf club. The 2004 ruling established that if the transferee company continued to use the golf club's name (which effectively functions as a trade name identifying the business to its members), it would generally be liable for refunding member deposits, unless "special circumstances" existed. Such special circumstances might include, for example, the transferee company promptly and clearly refusing existing members the preferential use of the golf facilities.

The 2008 case considered whether this same logic should apply to corporate demergers.

The Current Case: Company Demerger of the "B Golf Club"

The specific facts leading to the 2008 Supreme Court decision were as follows:

- Original Operator and Member's Deposit: A Co. operated a golf course under the name "B Golf Club," which had a deposit-based membership system. X Co. was a corporate member of B Golf Club and had paid a deposit of 35 million yen to A Co.

- Company Demerger: On January 8, 2003, A Co. underwent a "new establishment demerger" (新設分割 - shinsetsu bunkatsu). Through this process, A Co.'s golf course business was spun off and transferred to a newly created company, Y Co.

- Exclusion of Deposit Liabilities: The official demerger plan explicitly stated that Y Co., the new company, would not assume A Co.'s liabilities concerning the refund of golf club members' deposits.

- Continuity of Operations and Name: Despite this internal allocation of liabilities, Y Co. took over the operation of the golf course and, significantly, continued to operate it under the same established name, "B Golf Club."

- The "Written Request" to Members: Approximately three months after the demerger had taken effect (around April 15, 2003), A Co. and the new operator Y Co. jointly sent a letter, titled "An Written Request" (お願い書 - onegaisho), to all members of B Golf Club, including X Co. This letter:

- Informed the members that Y Co. had been newly established via the company demerger and would now be operating the golf course.

- Requested the members to convert their existing memberships (and the associated deposit claims) into shares of the new Y Co. The stated aim was to reform B Golf Club into a shareholder-member based system.

- X Co.'s Demand for Refund: X Co. chose not to convert its membership into shares of Y Co. On May 25, 2004 (after its deposit deferral period had ended), X Co. formally notified Y Co. of its intention to withdraw from B Golf Club and demanded the refund of its 35 million yen deposit from both A Co. (the original operator) and Y Co. (the new operator).

- High Court Ruling: The High Court had ruled that Y Co. was not liable for refunding X Co.'s deposit. While acknowledging that the principle of successor liability for continued use of a trade name could apply by analogy to company demergers, the High Court found that the sending of "this Written Request" to members constituted "special circumstances." It reasoned that this letter sufficiently informed members of the change in operators and the new proposed structure, meaning it was no longer reasonable for members to believe that Y Co. had assumed A Co.'s deposit refund obligations.

X Co. appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (June 10, 2008)

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous judgment regarding the main conclusion, overturned the High Court's decision and held Y Co. liable for refunding X Co.'s deposit.

Trade Name Liability Rule Applies Equally to Company Demergers

The Court decisively ruled that the legal principle established in its 2004 precedent concerning business transfers "applies equally" (同様に妥当する - dōyō ni datō suru) to company demergers.

- Reasoning for Analogous Application: The Supreme Court emphasized that a company demerger, like a business transfer, involves the succession of a business (in whole or in part) to a different legal entity through a legal act. If the successor company continues to use the established golf club name—which serves as a trade name and is the primary identifier of the business operator for its members—then, in the absence of clear "special circumstances," it is reasonable for club members to form certain beliefs. They might believe either that the business operator has not truly changed in substance, or that even if there has been a change in the legal entity, the new operator has assumed the debts and obligations associated with the ongoing business, such as the duty to refund member deposits.

- Demerger Plan Disclosure Insufficient: The Court also noted that the mere fact that company demerger plans (which would detail the allocation of assets and liabilities) are made available for public inspection at the company's head office does not alter this conclusion. It cannot generally be expected that individual golf club members will proactively seek out, access, and scrutinize these often complex legal documents to understand changes in liability for their deposits.

The "Written Request" Did NOT Constitute "Special Circumstances"

This was the pivotal point on which the Supreme Court reversed the High Court. The Supreme Court found that the letter sent by A Co. and Y Co. to the club members did not qualify as "special circumstances" that would negate Y Co.'s liability under the analogous application of Companies Act Article 22, Paragraph 1.

- The Court carefully analyzed the content of "this Written Request." It found that the letter merely informed members about Y Co.'s establishment through the demerger and requested them to convert their existing memberships into shares of Y Co. as part of a plan to reform the club into a shareholder-member system.

- Crucially, the letter did not explicitly and clearly state that Y Co. was disclaiming A Co.'s obligations to refund deposits for members who chose not to convert to shares.

- Furthermore, the letter did not indicate that members who refused to convert their memberships would be denied preferential use of the golf facilities or that their existing rights as members under A Co. would otherwise be terminated or diminished by Y Co.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the letter did not adequately or clearly inform members that Y Co. was not taking on the responsibilities associated with their existing memberships, including the obligation to refund deposits, if they chose not to accept the share conversion offer.

Outcome: Because no "special circumstances" were found to exist that would negate the general rule, the Supreme Court held that Y Co. was liable to refund X Co.'s 35 million yen deposit based on the analogous application of Companies Act Article 22, Paragraph 1. The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision concerning Y Co.'s liability and directly ordered Y Co. to make the payment to X Co., along with statutory interest. (While the main conclusion was unanimous, two Justices provided supplementary or concurring opinions that elaborated on why "this Written Request" was insufficient to constitute "special circumstances," with one Justice differing slightly on the precise reasoning for the insufficiency, particularly focusing on the more than three-month delay in sending the notice after the demerger, but ultimately agreeing with the outcome.)

Significance and Implications

The 2008 Supreme Court decision significantly impacts the rights of members of deposit-based golf clubs and sets important precedents for successor company liability in Japan.

- Enhanced Protection for Golf Club Members in Demergers: The ruling clearly extends the protective ambit of Companies Act Article 22, Paragraph 1 (or its predecessor) to situations involving company demergers. Successor companies that take over a golf business and continue using the established club name cannot easily shed the obligation to refund member deposits, even if the demerger plan internally assigns that liability elsewhere.

- High Bar for "Special Circumstances" and Importance of Clear Communication: The decision underscores that if a successor company in a demerger (or a business transfer) wishes to avoid liability for the predecessor's debts under the continued trade name principle, it must take clear, explicit, and timely steps to inform creditors (including club members) that it is not assuming those specific debts or that existing rights will be altered. A mere request to change membership terms, without clearly disclaiming prior obligations or detailing adverse consequences for non-acceptance, is insufficient.

- Focus on External Appearance and Reasonable Reliance by Members: The judgment reaffirms the importance of the external appearance of business continuity that is created by the continued use of a well-known club name. It protects the reasonable reliance of members who may assume that such continuity implies the continuation of existing obligations.

- A Check Against Potentially Abusive Corporate Restructurings: As noted in the PDF commentary accompanying this case, judicial doctrines like this serve as an important check against corporate restructurings that might be perceived as being designed to unfairly shed liabilities (like deposit refund obligations, which can be substantial for golf clubs) while retaining the profitable aspects and goodwill of an ongoing business.

Conclusion

The 2008 Supreme Court decision robustly extended the principle of successor company liability (when a trade name is continued) to the context of company demergers involving deposit-based golf clubs. It serves as a strong message that a successor company taking over a golf business through a demerger and continuing to operate under the existing, well-known club name will generally be held liable for refunding member deposits originally paid to the predecessor company. This liability can only be avoided if the successor company can demonstrate "special circumstances," which, as this case illustrates, requires more than simply informing members of the restructuring and requesting a change in their membership status; it necessitates a clear, unambiguous, and timely communication regarding the non-assumption of prior obligations or the alteration of existing membership rights. The ruling champions transparency and protects the reasonable expectations of club members during corporate reorganizations.