Japanese Personal Data Compliance: APPI, Cross-Border Transfers & Global Governance

TL;DR

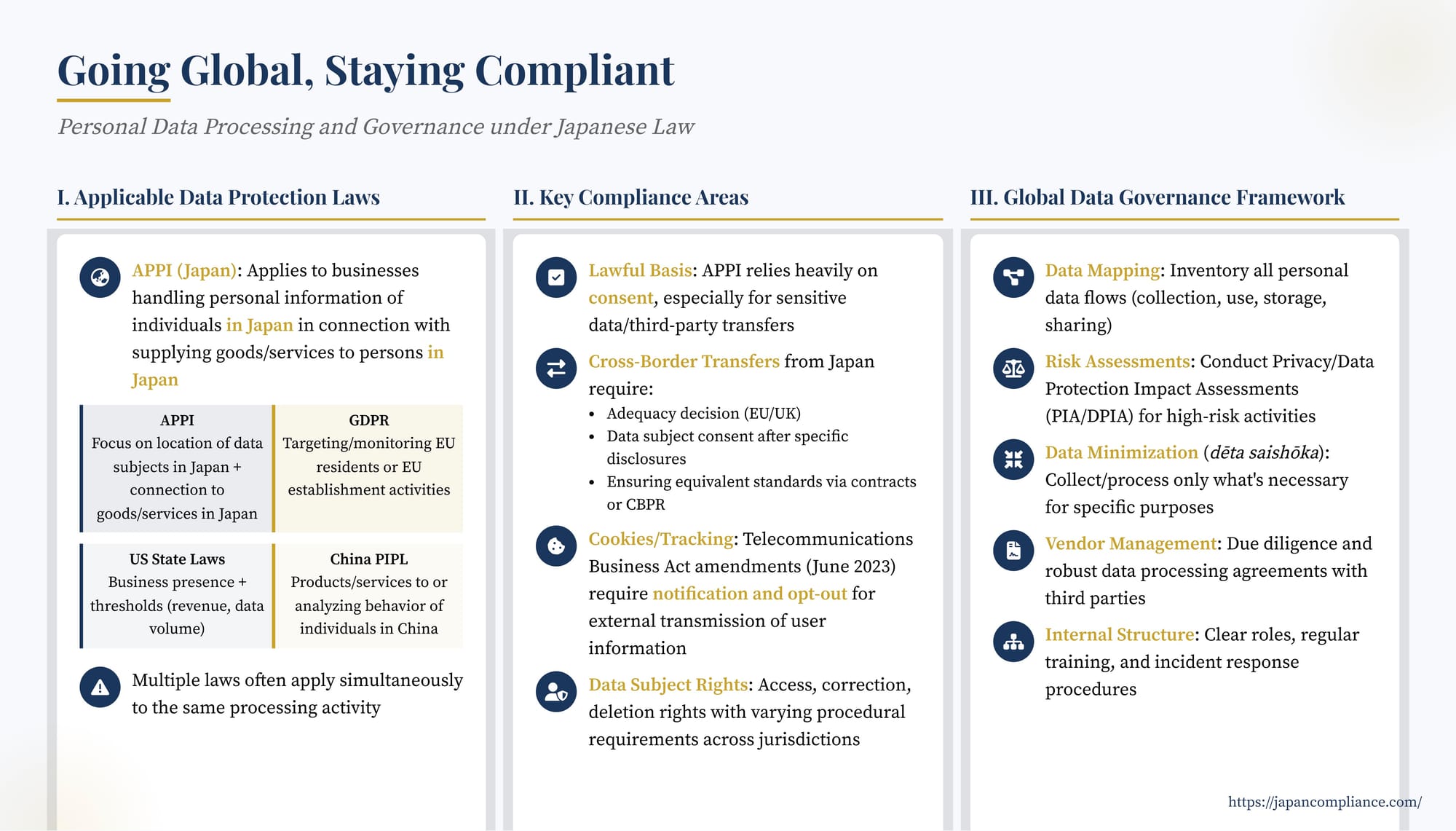

- Japan’s APPI applies extraterritorially; global firms must map data flows and lawful bases.

- Cross-border transfers from Japan need adequacy, consent, or APPI-equivalent safeguards.

- EU-GDPR, US state laws, China’s PIPL often overlap—build a multi-layer governance model.

- New 2023 Telecom Business Act “external transmission” rule adds cookie/opt-out duties.

- A global framework of data-mapping, DPIAs, minimisation, and robust vendor contracts is essential.

Table of Contents

- The Tangled Web: Determining Applicable Data Protection Laws

- Key Compliance Areas in a Global Context

- Building a Global Data Governance Framework

- Conclusion

In today's interconnected economy, processing personal data is not just necessary for business; it's fundamental. From customer interactions and employee management to supply chains and digital marketing, data flows across borders with unprecedented ease. However, this ease of flow brings complexity: navigating the diverse and rapidly evolving landscape of data protection regulations across different countries.

For multinational corporations, particularly those with operations, customers, or partners in Japan, understanding the requirements of Japan's Act on the Protection of Personal Information (個人情報保護法 - Kojin Jōhō Hogo Hō, "APPI") and how it interacts with other major global regimes like the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), various US state laws (like the CCPA/CPRA), and China's Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) is crucial. Establishing a robust global data governance framework that respects these varying requirements is no longer optional, but a strategic imperative.

This article explores the challenges of managing personal data in a global context involving Japan, focusing on determining applicable laws, key compliance obligations like cross-border transfers and consent, and strategies for building effective data governance.

1. The Tangled Web: Determining Applicable Data Protection Laws

A primary challenge for global businesses is identifying which data protection laws apply to their processing activities. Many modern data protection laws assert extraterritorial reach, meaning they can apply even if the business itself is not physically located in that jurisdiction.

- Japan's APPI (Extraterritorial Application - Art. 171): The APPI applies to businesses outside Japan if they handle the personal information of individuals located in Japan, and this handling is done in connection with supplying goods or services to persons (individuals or corporations) located in Japan. Nationality is irrelevant; the key is the data subject's presence in Japan during the processing related to the supply of goods/services to Japan. Internal global employee data management might fall outside this scope if not directly tied to providing goods/services to Japan.

- EU's GDPR (Art. 3): The GDPR famously has broad extraterritorial scope. It applies to processing by controllers/processors not established in the EU if their activities relate to:

- Offering goods or services (even if free) to data subjects in the EU (the "targeting" criterion).

- Monitoring the behavior of data subjects as far as their behavior takes place within the EU (the "monitoring" criterion, often relevant for online tracking, cookies, and profiling).

It also applies, regardless of where processing occurs, to processing in the context of the activities of an establishment of a controller or processor in the EU. Given the broad interpretation of "establishment activities," many global companies find GDPR applies due to their EU presence.

- US State Laws (e.g., CCPA/CPRA): The US lacks a comprehensive federal privacy law, creating a complex patchwork of state regulations. Laws like California's CCPA/CPRA apply based on criteria like doing business in the state and meeting certain revenue, data processing volume, or data brokerage thresholds. Determining applicability requires analyzing operations on a state-by-state basis for an increasing number of states with their own laws (including Colorado, Connecticut, Virginia, Utah, Iowa, Indiana, Tennessee, Montana, Texas, Delaware, Oregon, Florida, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Maryland, Nebraska, Kentucky, Rhode Island, Minnesota, with varying effective dates through 2026).

- China's PIPL: Similar in structure to GDPR's extraterritorial reach, China's PIPL applies to processing activities outside China if they relate to:

- Providing products or services to individuals in China.

- Analyzing or assessing the behavior of individuals in China.

- Other circumstances specified by law.

Implication: Multinational companies must conduct careful assessments, often involving legal counsel, to map their data flows and determine which laws apply to different processing activities based on the location of the data subjects, the business's presence, and the nature of the activity (e.g., targeting specific markets). It's common for multiple laws (e.g., APPI and GDPR) to apply simultaneously to the same processing activity involving data from different regions.

2. Key Compliance Areas in a Global Context

While specific requirements vary, several core areas consistently demand attention under major data protection regimes, including Japan's APPI. Effective global governance requires strategies to address these common themes while accommodating local nuances.

a) Lawful Basis for Processing and Transparency

- Lawful Basis: Most comprehensive data protection laws require a valid legal basis for processing personal data. Under GDPR, these include consent, contractual necessity, legal obligation, vital interests, public task, and legitimate interests. Japan's APPI, while often relying heavily on consent in practice (especially for sensitive data or certain third-party transfers), also recognizes other bases like contractual necessity and legal obligations. Establishing and documenting the lawful basis for each processing activity is fundamental.

- Transparency (Privacy Notices): Providing clear, accessible information to data subjects about how their data is processed is a universal requirement. However, the level of detail mandated differs. APPI requires specifying the purpose of use, disclosure about joint use or third-party provision, contact information, and procedures for exercising data subject rights. GDPR requires more extensive disclosures, including the legal basis for processing, data retention periods, detailed information on international transfers and safeguards, and the right to lodge complaints with supervisory authorities. Global privacy notices often adopt a layered approach, providing core information applicable worldwide with links or sections detailing jurisdiction-specific requirements (like those under APPI or CCPA/CPRA).

b) Cross-Border Data Transfers

Transferring personal data across national borders is heavily regulated and a major operational challenge for global companies. Mechanisms vary significantly:

- Japan (APPI Art. 28): Transferring personal data from Japan to a third party outside Japan generally requires one of the following:

- Adequacy Decision: Transfer to a country recognized by Japan's Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC) as having an equivalent level of protection. Currently, only the EU/EEA and the United Kingdom have this status.

- Data Subject Consent: Obtaining the individual's prior consent after providing specific information about the destination country's data protection environment, the recipient's security measures, etc. This can be operationally complex to obtain meaningfully for each transfer.

- Equivalent Standards: Ensuring the recipient abroad implements data protection measures equivalent to those required by the APPI. This is typically achieved through:

- Contractual Clauses: Data transfer agreements obligating the recipient to meet APPI standards. The PPC provides guidance on expected contractual content.

- Intra-Group Rules: While not explicitly named Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) like GDPR, internal group policies can potentially serve this function if they meet the required standards, although this is less commonly relied upon in practice compared to contracts.

- Approved Frameworks: Transfer to a recipient certified under an internationally recognized framework approved by the PPC (currently the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules - CBPR - system).

- EU (GDPR Chapter V): Transfers outside the EU/EEA are restricted unless:

- Adequacy Decision: The European Commission has determined the destination country ensures adequate protection (Japan benefits from such a decision, facilitating transfers from the EU to Japan, subject to certain supplementary rules for data covered by the decision).

- Appropriate Safeguards: Mechanisms like Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) approved by the European Commission, or Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) for intra-group transfers, are implemented.

- Derogations (Exceptions): Applicable only in specific situations, such as the data subject's explicit, informed consent for a specific transfer, contractual necessity, or important reasons of public interest. Reliance on consent as a regular transfer mechanism is discouraged.

- China (PIPL): China imposes arguably the strictest requirements. Transferring data outside mainland China requires meeting both a condition for the transfer and obtaining separate consent:

- Conditions: Passing a mandatory security assessment conducted by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) (required for critical information infrastructure operators or large-volume data processors), obtaining certification from a recognized institution, entering into the standard contract formulated by the CAC, or meeting other legal/administrative conditions.

- Consent: Obtaining the individual’s separate, informed consent for the cross-border transfer is generally required in addition to meeting one of the conditions above.

Implication: Global data transfer strategies must be multi-faceted. Companies need mechanisms (often contractual, like SCCs or APPI-compliant clauses) to cover transfers from Japan to non-adequate countries (like the US) and from the EU to non-adequate countries. The Japan-EU mutual adequacy decision simplifies transfers between these two regions. Transfers involving China require navigating its specific, often more burdensome, requirements including potentially government assessments and separate consents.

c) Cookies, Tracking, and Digital Marketing

- Cookies/Tracking Tech: Rules around cookies and similar online tracking technologies vary widely.

- EU: The ePrivacy Directive (and GDPR) generally require prior, informed consent (opt-in) for placing non-essential cookies or accessing information on a user's device.

- Japan: The APPI itself doesn't directly regulate cookies unless the cookie data, alone or combined with other information, identifies an individual (making it personal information). However, the amended Telecommunications Business Act (effective June 2023) imposes obligations on many online service providers (including website operators using third-party tags) when transmitting user information (which can include cookie IDs, Browse history) to external parties. This generally requires providing notification about the external transmission or making such information readily accessible (e.g., via a cookie policy), and offering an opt-out mechanism (though consent can also satisfy the requirement). This moves Japan closer to, but still distinct from, the EU's opt-in model.

- Direct Marketing (Email): Consent requirements also differ.

- Japan: Laws like the Act on Specified Commercial Transactions and the Act on Specified E-Mail Transmission generally require prior consent (opt-in) for sending commercial emails.

- US: The CAN-SPAM Act operates primarily on an opt-out basis, allowing businesses to send commercial emails provided they meet labeling requirements and offer a clear way for recipients to unsubscribe.

- EU: GDPR and ePrivacy rules generally require opt-in consent for unsolicited commercial emails to individuals (with some exceptions for existing customer relationships).

Implication: Global digital marketing requires careful implementation of consent/notification mechanisms tailored to the target jurisdiction. Cookie banners and email marketing lists need to accommodate differing opt-in/opt-out requirements.

d) Data Subject Rights

Most comprehensive laws grant individuals rights over their personal data, such as rights of access, correction, deletion, and restriction of processing. While the core rights are similar across APPI, GDPR, CCPA/CPRA etc., the specific scope, exceptions, and procedures for handling requests can differ. Global governance must include processes to receive, verify, and respond to data subject requests in compliance with all applicable laws within statutory timeframes.

3. Building a Global Data Governance Framework

Given this complex legal mosaic, a structured approach to data governance is essential. This involves creating internal systems and processes to manage data processing compliantly and ethically across the organization. Key components include:

- Data Mapping: The absolute foundation. This involves comprehensively inventorying personal data across the organization: What data is collected? From whom? Why (purpose)? How is it used? Where is it stored? Who is it shared with (internal departments, third-party vendors, across borders)? How long is it kept? Understanding these flows is critical for identifying applicable laws and risks.

- Risk Assessments (PIA/DPIA): Regularly conduct Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) or, where required (e.g., under GDPR Art. 35 or PIPL Art. 55), Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs). These structured assessments help identify and mitigate privacy risks associated with specific processing activities, especially new projects, high-risk processing, or international data flows.

- Policy Harmonization and Localization: Develop a core set of global data protection policies reflecting high standards (often using GDPR as a benchmark due to its stringency and influence). These global policies should then be supplemented with specific addenda, procedures, or notices addressing unique requirements of key local laws like Japan's APPI (e.g., specific cross-border transfer rules, handling of sensitive information), US state laws, or China's PIPL.

- Embracing Data Minimization: Adopt the principle of data minimization (データ最小化 - dēta saishōka) as a core tenet. Collect and process only the personal data that is strictly necessary to achieve a legitimate, specified purpose. Avoid collecting data "just in case." This not only aids compliance (reducing the scope of data subject to regulation) but also reduces security risks and data management costs. A cautionary tale comes from Germany where a real estate company faced large fines for maintaining a "data graveyard" – archiving old tenant data indefinitely without a proper basis or deletion process.

- Vendor Due Diligence and Contracts: Rigorously vet third-party vendors who will process personal data on the company's behalf. Ensure robust data processing agreements (DPAs) are in place, contractually obligating vendors to protect the data according to applicable legal standards (including flow-down provisions for sub-processors) and addressing cross-border transfer requirements if applicable.

- Internal Structure and Training: Establish clear internal roles and responsibilities for data protection compliance (appointing a Data Protection Officer - DPO - where legally required or beneficial). Implement regular, mandatory data protection training for all relevant employees. Develop and test an incident response plan to handle potential data breaches effectively.

Conclusion

Operating globally in the digital age inevitably involves processing personal data across borders, triggering a complex interplay of national and regional data protection laws. For companies with a presence in Japan, compliance requires understanding not only the nuances of the APPI, including its cross-border transfer rules and potential extraterritorial reach, but also how it interacts with other major regimes like GDPR and the evolving landscape of US state privacy laws.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution. However, a proactive, risk-based global data governance framework – built on thorough data mapping, regular risk assessments, harmonized yet locally adapted policies, and core principles like transparency and data minimization – provides the essential structure. This allows businesses not only to navigate the intricate legal requirements and mitigate risks but also to build trust with customers and partners by demonstrating a genuine commitment to responsible data stewardship in Japan and beyond.

- Japan's APPI Explained: Data Privacy Compliance for U.S. Companies

- Japan's New Data Privacy Era: What the Integrated Personal Information Protection Act Means for U.S. Businesses

- Japan's Evolving Platform Regulation Landscape: An Overview for Global Businesses

- Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC) – Laws & Policies