Ghost Assets? Japanese Supreme Court on Inheriting Tax Refund Claims from Cancelled Assessments

Date of Judgment: October 15, 2010

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Inheritance Tax Reassessment Disposition (平成21年(行ヒ)第65号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

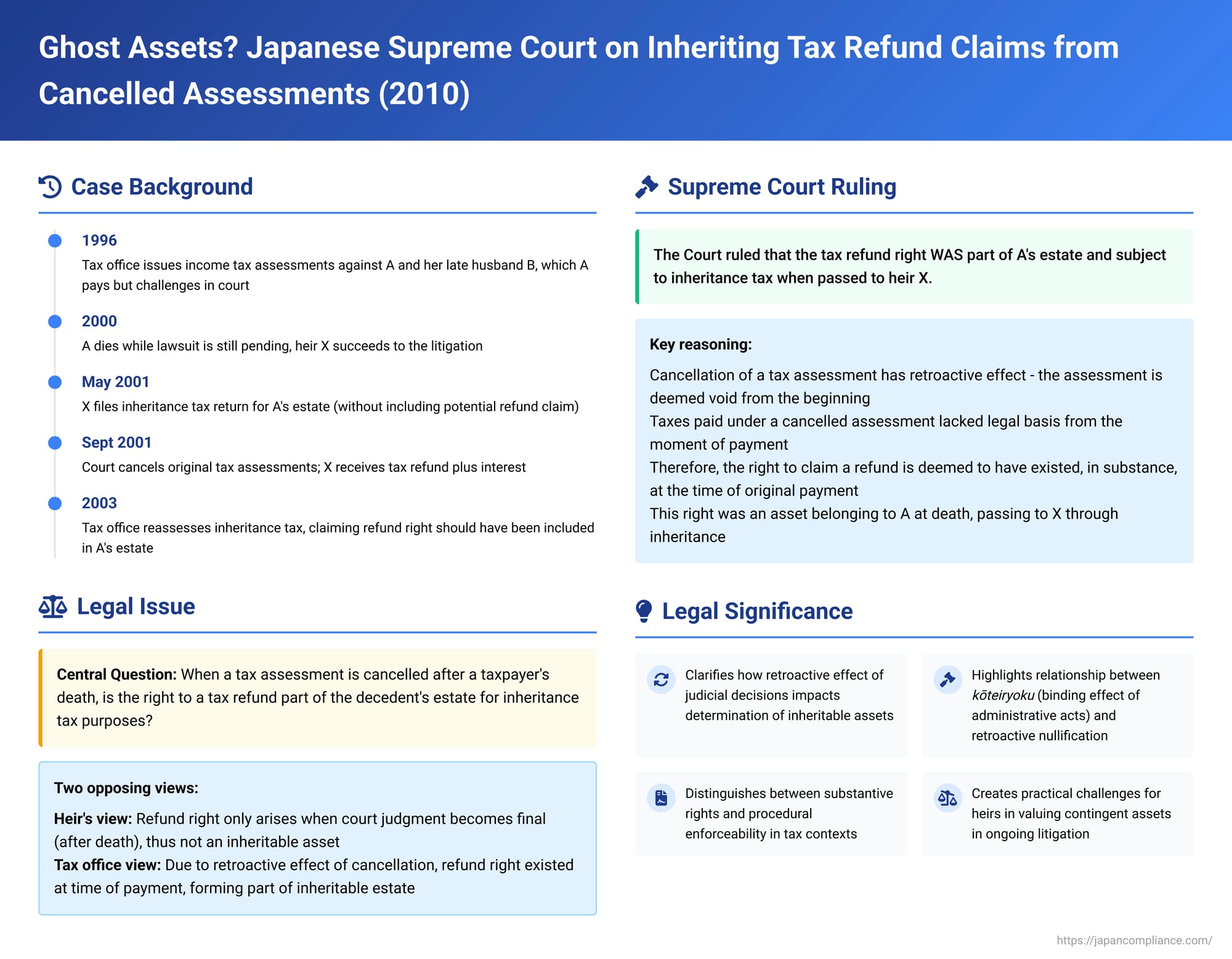

In a significant decision on October 15, 2010, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified whether a right to a tax refund, which only became definitively recoverable after a taxpayer's death due to a court judgment cancelling a previous tax assessment, should be included as an asset in the deceased's taxable estate. The Court held that due to the retroactive effect of such a cancellation judgment, the right to the refund is deemed to have existed at the time of the original tax payment and thus forms part of the inheritable estate.

The Tax Dispute Spanning Generations

The case involved a sequence of events beginning with income tax assessments issued against a taxpayer, A, and her predeceased husband, B.

- Initial Tax Dispositions: In February 1996, the competent tax administrative agency issued corrective income tax assessments and underpayment additional tax assessments against A for her 1993 income tax, and also against her late husband B (who had passed away in September 1994) for his 1992 income tax (collectively referred to as "the separate dispositions").

- Payment and Legal Challenge by A: A duly paid the amounts determined by these separate dispositions, covering the principal income tax, underpayment additional tax, and delinquency tax. However, in April 1997, A initiated a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of these separate dispositions.

- A's Death and Succession to Lawsuit by Heir X: A passed away in July 2000, while her lawsuit challenging the separate dispositions was still pending. Her heir, X (the appellant in the Supreme Court case), succeeded to A's position as the plaintiff in this ongoing litigation.

- X's Inheritance Tax Filing: In May 2001, X filed an inheritance tax return for the assets acquired from A's estate. At this point, the outcome of the separate lawsuit was still unknown, and presumably, the potential income tax refund was not included as an asset in this initial inheritance tax declaration.

- Successful Outcome in Separate Lawsuit and Refund: In September 2001, the Oita District Court rendered a judgment cancelling the separate dispositions that had been issued against A and B. This judgment became final and binding. Consequently, in December 2001, the tax administrative agency refunded to X (as A's heir) the principal amounts of income tax, underpayment additional tax, and delinquency tax that A had originally paid under the now-nullified separate dispositions ("the subject overpayment"). Additionally, X received refund interest (還付加算金 - kanpu kasankin) as stipulated by Article 58 of the General Act of National Taxes.

- X's Income Tax Treatment of the Refund: In March 2002, X filed an income tax return for the 2001 tax year, declaring both the refunded principal amount of the overpayment and the associated refund interest as "temporary income" for 2001.

- Inheritance Tax Reassessment by Tax Office: In April 2003, the tax office issued a corrective assessment for the inheritance tax payable by X on A's estate ("the subject reassessment"). The tax office's position was that the principal amount of "the subject overpayment" (i.e., the refunded taxes, excluding the refund interest) constituted an asset that X had inherited from A. Therefore, this amount should have been included in A's taxable estate at the time of her death. Alongside this reassessment increasing the inheritance tax due, an underpayment additional tax was also imposed on X. Concurrently, the tax office issued a downward corrective assessment for X's 2001 income tax, effectively removing the principal amount of the overpayment from X's temporary income for that year (as it was now being treated as an inherited asset).

- Challenge to Inheritance Tax Reassessment: X disputed the inheritance tax reassessment and the associated penalty. After an administrative appeal process, the National Tax Tribunal rejected X's claim concerning the main reassessment but cancelled the underpayment additional tax. X then filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the inheritance tax reassessment itself.

The Oita District Court (first instance in the inheritance tax case) ruled in favor of X. It held that for inheritance tax purposes, an asset must have an ascertainable economic value and be succeeded to by the heir at the time of the decedent's death. Since, at the time of A's death, the separate lawsuit was still pending and the outcome uncertain, the court found that A's right to a tax refund had not yet actually arisen. It reasoned that such a refund claim only comes into existence when a court judgment cancelling the prior tax assessment becomes final and binding. Thus, the refund claim was not part of A's estate.

The Fukuoka High Court (appellate court) reversed this decision, ruling in favor of the State (Y). The High Court emphasized the retroactive effect of a court judgment that cancels an administrative disposition. Such a cancellation means the original disposition is treated as if it never existed from the outset. Consequently, the taxes paid by A under these (now retroactively nullified) dispositions lacked any legal basis from the very moment of payment. This, in turn, meant that A's right to claim a refund for this overpayment also arose substantively at the moment of payment and was therefore an asset belonging to A's estate at the time of her death. X appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: When Does a Tax Refund Claim Become an Inheritable Asset?

The central legal question before the Supreme Court was: When a taxpayer (A) pays taxes under an assessment which is subsequently cancelled by a court judgment that becomes final after A's death (with the lawsuit having been continued by A's heir, X), does the right to a refund of those taxes constitute an asset of A's estate that is subject to inheritance tax in X's hands? Or does this right to a refund only come into existence when the cancelling judgment becomes final and binding, meaning it is an asset acquired directly by the heir (X) post-inheritance and thus not part of A's inheritable estate? The answer hinged critically on the legal effect, particularly the retroactivity, of a judgment that cancels an administrative act like a tax assessment.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Refund Right Relates Back to Time of Payment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the Fukuoka High Court's decision. The Supreme Court ruled that the right to the tax refund was indeed an asset of A's estate at the time of her death and was therefore subject to inheritance tax.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Retroactive Effect of a Cancellation Judgment: When a court judgment that cancels an income tax corrective assessment and an underpayment additional tax disposition becomes final and binding, these administrative dispositions are deemed to have lost their legal effect retroactively to the time they were originally made (処分時にさかのぼってその効力を失う - shobun-ji ni sakanobotte sono kōryoku o ushinau).

- Legal Basis of Original Tax Payment Lost Retroactively: As a direct consequence of this retroactive nullification of the tax assessments, the income tax, underpayment additional tax, and delinquency tax that had been paid by A based on these (now voided) dispositions are considered to have lacked any legal basis from the very moment of their payment (納付の時点から法律上の原因を欠いていた - nōfu no jiten kara hōritsujō no gen'in o kaiteita).

- Timing of the Existence of the Refund Claim: Based on this retroactive loss of legal basis for the original tax payment, the Supreme Court concluded that the right to claim a refund for this overpayment (過納金の還付請求権 - kanōkin no kanpu seikyūken) is deemed to have already arisen, in substance, at the time of the original payment by A.

- Conclusion for Inheritance Tax Purposes: Therefore, in a situation where a decedent (like A) had paid taxes pursuant to such dispositions and had initiated a lawsuit challenging their validity, and where, following the decedent's death, an heir (like X) succeeds to that lawsuit and ultimately obtains a final and binding judgment cancelling those dispositions, the right to the refund of the taxes paid by the decedent constitutes an asset of the decedent's estate. As such, this right to a refund is properly included in the taxable estate and is subject to inheritance tax as property acquired by the heir through inheritance from the decedent.

The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment, which was based on the same line of reasoning, to be correct and affirmed it.

Analysis: Navigating Kōteiryoku and Retroactivity

This Supreme Court decision provides crucial clarification on how the retroactive effect of judicial decisions impacts the determination of inheritable assets for tax purposes.

- The Role of Kōteiryoku (Binding Effect of Administrative Acts): A key background concept is the "public force" or binding effect (kōteiryoku) of administrative acts in Japanese law. Generally, an administrative act like a tax assessment, even if potentially flawed, is treated as legally valid and effective unless and until it is formally cancelled or revoked through prescribed procedures (administrative appeal or a specific type of lawsuit for revocation). The PDF commentary on this case notes that, traditionally, an overpayment of tax made pursuant to such a (then-valid) administrative act (kanōkin) was distinguished from an erroneous payment made without any underlying legal basis from the start (gonōkin). For a kanōkin, the right to demand a refund as unjust enrichment was seen as procedurally blocked by the kōteiryoku of the assessment until that assessment was formally nullified.

- Retroactive Nullification as Key: The Supreme Court's decision emphasizes that the court judgment cancelling the original tax assessment has a powerful retroactive effect. It doesn't just nullify the assessment from the date of the judgment; it renders it void ab initio (from the beginning). This retroactive nullification effectively removes the kōteiryoku that previously gave legal cover to the State's retention of the tax.

- Substantive Right vs. Procedural Enforceability: The implication of the Court's reasoning is that while the procedural ability to enforce a refund claim might be suspended until the offending assessment is cancelled, the substantive right to the funds (because the State lacked a valid legal basis to collect or retain them, once the assessment is retroactively deemed void) can be considered to have existed from the moment of the wrongful payment. The subsequent court judgment cancelling the assessment then "actualizes" or makes fully enforceable this pre-existing, albeit latent, right.

- Distinction from Changes in Private Law Rights: Legal commentators suggest that this scenario, involving the retroactive nullification of a public administrative act (a tax assessment), is distinct from situations where purely private law rights (e.g., rights under a contract) might be altered retroactively after a person's death (for instance, through a contract rescission). In the tax context of this case, the very legal foundation for the State having received the money was retroactively eliminated.

- Practical Challenges for Heirs in Valuing Contingent Assets: This ruling underscores a practical difficulty for heirs. If a deceased person was involved in litigation that could result in a recovery of assets (like a tax refund), that contingent claim might need to be considered as part of the inheritable estate, even if its value and likelihood of success are uncertain at the time of death and inheritance tax filing. If the contingent claim is later valued differently or is ultimately unsuccessful, this could necessitate subsequent adjustments or corrections to the inheritance tax assessment. The judgment implies that the potential recovery amount is the value to be included.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2010 judgment in this case provides an important clarification regarding the inclusion of post-mortem finalized tax refund claims in a decedent's taxable estate. By underscoring the profound retroactive effect of a court judgment that cancels a tax assessment, the Court established that the right to a refund for taxes paid under such a (subsequently nullified) assessment is deemed to have arisen at the time of the original wrongful payment. Consequently, if the taxpayer dies before the refund is finalized, this right to a refund passes as an asset to their heirs and is subject to inheritance tax. This decision highlights how fundamental principles of administrative law, such as the retroactive effect of judicial review, can significantly impact tax liabilities, even across generations.