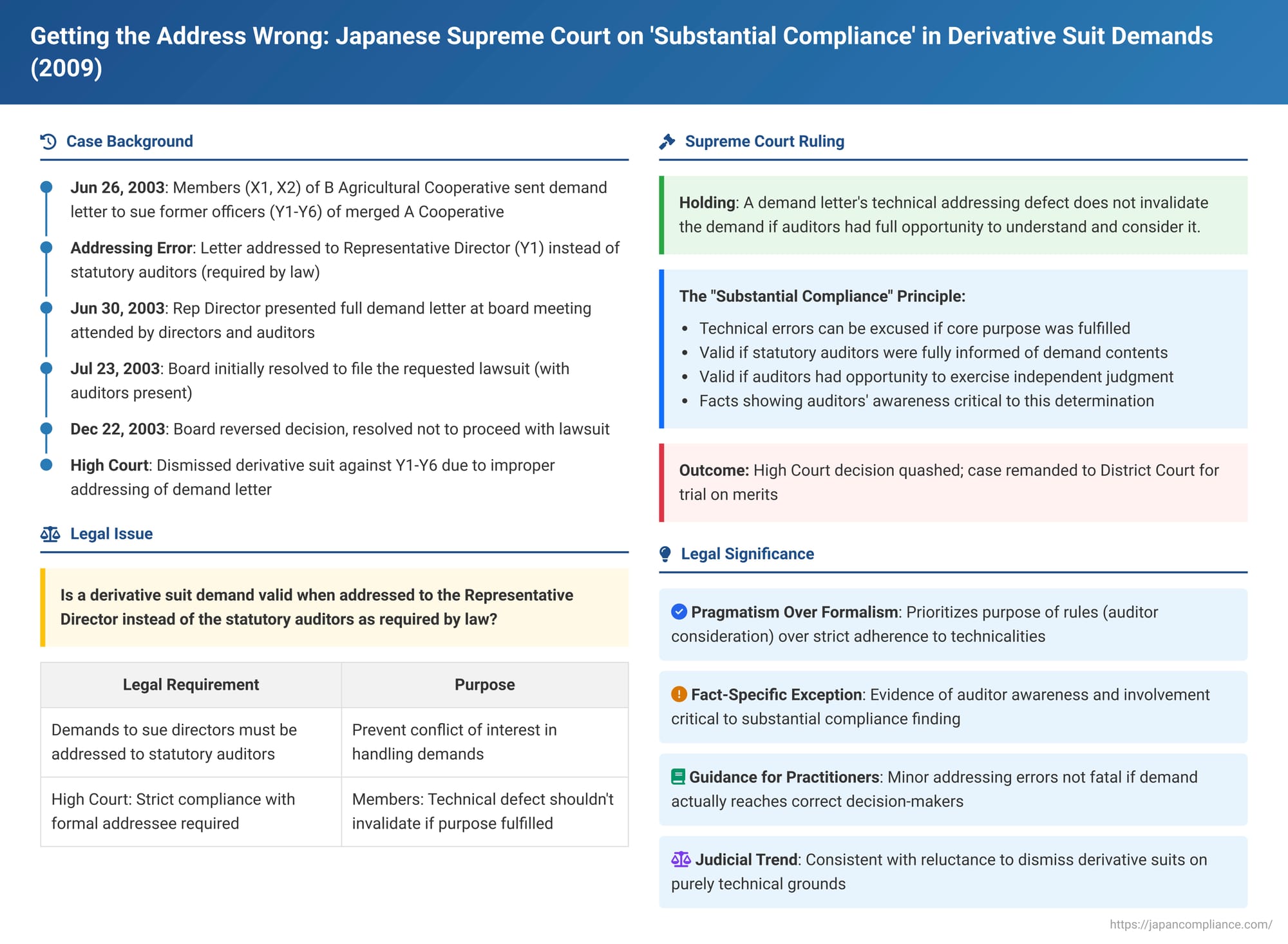

Getting the Address Wrong: Japanese Supreme Court on 'Substantial Compliance' in Derivative Suit Demands

Date of Judgment: March 31, 2009

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

Derivative lawsuits are a powerful mechanism enabling shareholders (or members of a cooperative) to hold company directors or cooperative officers accountable for misconduct by suing on behalf of the organization itself. However, before initiating such a suit, Japanese law typically requires the shareholder/member to first formally demand that the company or cooperative file the lawsuit against the allegedly wrongdoing officers. This pre-suit demand has specific procedural requirements, including to whom it must be addressed.

But what happens if there's a minor technical error in this demand – for instance, if the letter is addressed to the company's CEO (Representative Director) instead of its statutory auditors, who are usually the correct recipients when directors are the targets? Can such a formal defect derail an otherwise meritorious derivative claim? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this nuanced issue in its decision on March 31, 2009.

The Derivative Suit Demand: Purpose and Formalities

The requirement for a pre-suit demand in derivative litigation serves a crucial purpose: it gives the company or cooperative an opportunity to assess the allegations and decide whether to take legal action itself against the implicated officers. This respects the organization's primary right to manage its own affairs, including litigation.

When the potential defendants are the company's own directors, there's an inherent conflict of interest if the demand to sue them is handled by those same directors or by management under their control. To ensure impartiality, Japanese law (both the Agricultural Cooperatives Act, as in this case, and analogous provisions in company law) generally stipulates that when a demand is made to sue directors, it is the statutory auditors (監事 - kanji) who should represent the company/cooperative in receiving and considering this demand. Auditors are expected to exercise independent judgment in the best interests of the organization.

The Case of B Agricultural Cooperative

The case involved members of B Agricultural Cooperative (hereinafter "B Coop") who sought to hold former officers of A Agricultural Cooperative ("A Coop," which had merged to form part of B Coop) liable for alleged financial mismanagement.

- The Alleged Wrongdoing: The plaintiffs, X et al., members of B Coop, believed that Y et al., former officers of A Coop, were liable to B Coop. This liability stemmed from an alleged agreement related to the merger that formed B Coop, specifically concerning the under-provisioning of bad debt reserves by A Coop prior to the merger. X et al. contended that these former officers should compensate B Coop for the shortfall.

- The Demand to Sue: On June 26, 2003, two of the plaintiffs, X1 and X2, sent a formal demand letter to B Coop, requesting that it initiate a lawsuit against Y et al. (the former officers of A Coop) to recover the alleged losses.

- The Defect in Addressing: However, this demand letter was addressed to Y1, who was the Representative Director and Chairman of B Coop, naming him as the representative of B Coop for the purpose of the demand. The letter should have been formally addressed to the statutory auditors of B Coop, as the individuals being targeted (Y et al.) included persons who were now directors of B Coop (Y1 through Y6 were current directors of B Coop at that time, and also former officers of A Coop).

- B Coop's Internal Deliberations: Despite this addressing error:

- On June 30, 2003, Representative Director Y1 presented the demand letter to a meeting of B Coop's board of directors. This meeting was attended by both directors and B Coop's statutory auditors. The full contents of the demand letter were read out loud.

- Following this, on July 23, 2003, B Coop's board of directors, with the auditors present, actually resolved to file the lawsuit against Y et al., as requested in the demand letter. Lawyers were retained, and demand letters were dispatched to the targeted former officers.

- However, on December 22, 2003, B Coop's board reversed its earlier decision and resolved not to proceed with the lawsuit, citing the cooperative's worsening financial situation and a desire to avoid internal disputes while considering other measures like a potential business transfer. B Coop never ultimately filed the suit.

- The Derivative Lawsuit and Lower Court Ruling: When B Coop failed to sue, X et al. initiated a members' derivative lawsuit. The High Court, however, dismissed the part of the lawsuit against those defendants (Y1 through Y6) who were current directors of B Coop at the time the demand was made. The High Court reasoned that the initial demand was improper because it was addressed to the Representative Director instead of the statutory auditors, thus failing to meet the legal requirements for a valid pre-suit demand against current directors.

X et al. appealed this part of the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 31, 2009)

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous judgment, overturned the High Court's dismissal concerning defendants Y1-Y6.

Purpose of Auditor Representation in Receiving Demands

The Court began by acknowledging the general rule: statutory auditors should represent the cooperative (or company) in receiving a demand from members/shareholders to sue its directors. The rationale, the Court explained, is to prevent a conflict of interest. If the demand were made to the Representative Director concerning fellow directors, the Representative Director might be inclined to protect colleagues rather than act solely in the cooperative's best interest by deciding not to sue. Entrusting this to the independent auditors safeguards against this potential bias.

The "Substantial Compliance" Exception

However, the Supreme Court then articulated a crucial exception based on the principle of "substantial compliance." It held that even if a demand letter incorrectly names the Representative Director as the addressee (instead of the statutory auditors), the demand may still be considered valid if a specific condition is met: if the statutory auditors were, in fact, given a full and fair opportunity to accurately understand the contents of the demand and to independently exercise their own judgment on whether the cooperative should initiate the requested lawsuit against the directors.

The Court reasoned that if the auditors are placed in a situation that is functionally equivalent to having received a correctly addressed demand letter, then the technical defect in the addressee should not be fatal to the validity of the demand. In such circumstances, a subsequently filed derivative suit should be treated as if a formally proper demand had been made.

Application to the Facts of the B Coop Case

Applying this "substantial compliance" principle to the facts before it, the Supreme Court noted:

- The Representative Director of B Coop (Y1) had read the entire contents of the demand letter from X1 and X2 aloud at a board of directors' meeting on June 30, 2003.

- This meeting was attended not only by directors but also by B Coop's statutory auditors.

- Subsequently, the board, with the auditors present, deliberated on the demand and initially resolved on July 23, 2003, to file the very lawsuit requested by X1 and X2.

Based on these facts, the Supreme Court concluded that the statutory auditors of B Coop had, by June 30, 2003, been fully apprised of the demand letter's contents and had a clear opportunity to form their own independent judgment regarding whether B Coop should sue its directors Y1-Y6.

Outcome: Therefore, the derivative suit initiated by X et al. against directors Y1-Y6 should be treated as if a formally proper pre-suit demand had been made to the auditors. The High Court's dismissal of this part of the suit due to an improper demand was an error of law. The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision concerning Y1-Y6 and remanded that part of the case (with the first instance judgment on Y1-Y6 also being set aside) to the District Court for further proceedings on the merits.

Significance and Implications

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision offers important practical guidance on the procedural requirements for derivative lawsuits in Japan:

- Pragmatism Over Strict Formalism: The ruling demonstrates a pragmatic judicial approach, prioritizing the underlying purpose of the pre-suit demand rule—ensuring that the auditors (or other designated independent body) have a genuine opportunity to consider the demand—over an overly strict adherence to formal addressing requirements. A minor technical error that does not actually prejudice the auditors' ability to fulfill their statutory role may be excused.

- Guidance for Initiating Derivative Suits: While it is always advisable for members or shareholders to follow procedural requirements precisely, this decision provides some reassurance that an inadvertent minor error in addressing the demand letter may not automatically bar an otherwise valid derivative claim, provided the substance of the demand reaches the correct decision-makers in a timely and comprehensive manner.

- Fact-Specific Nature of the Exception: It is important to note, as academic commentary suggests, that the Supreme Court's willingness to overlook the defect was likely influenced by the specific facts of this case, which clearly demonstrated the auditors' awareness and active involvement in considering the demand (evidenced by the board's initial resolution, with auditor presence, to file the suit). The ruling should not be interpreted as a broad license to disregard procedural formalities, especially if auditor awareness or their opportunity to act independently is not clearly established.

- Alignment with Broader Judicial Trends: The decision is seen by commentators as consistent with other judicial rulings where courts have been reluctant to dismiss derivative suits on purely technical grounds if the company or its auditors have, through their actions or inactions, already indicated their stance on pursuing the litigation (e.g., by definitively deciding not to sue, or by actively defending the accused directors, thereby making the formal demand somewhat futile).

Conclusion

The 2009 Supreme Court decision in the B Agricultural Cooperative case provides a valuable clarification regarding the pre-suit demand requirement in Japanese derivative litigation. It establishes that a technical defect, such as misaddressing the demand letter to the representative director instead of the statutory auditors, will not necessarily invalidate the demand or bar a subsequent derivative suit if the core purpose of the rule—ensuring that the auditors are fully informed and have a genuine opportunity to exercise their independent judgment—is substantially fulfilled. This ruling promotes a sensible balance between upholding procedural propriety and ensuring that meritorious derivative claims, vital for corporate and cooperative accountability, can proceed effectively.