Japan Supreme Court 2017 Survivor‑Pension Case: Why Age Rules for Widowers Survived an Equality Challenge

TL;DR

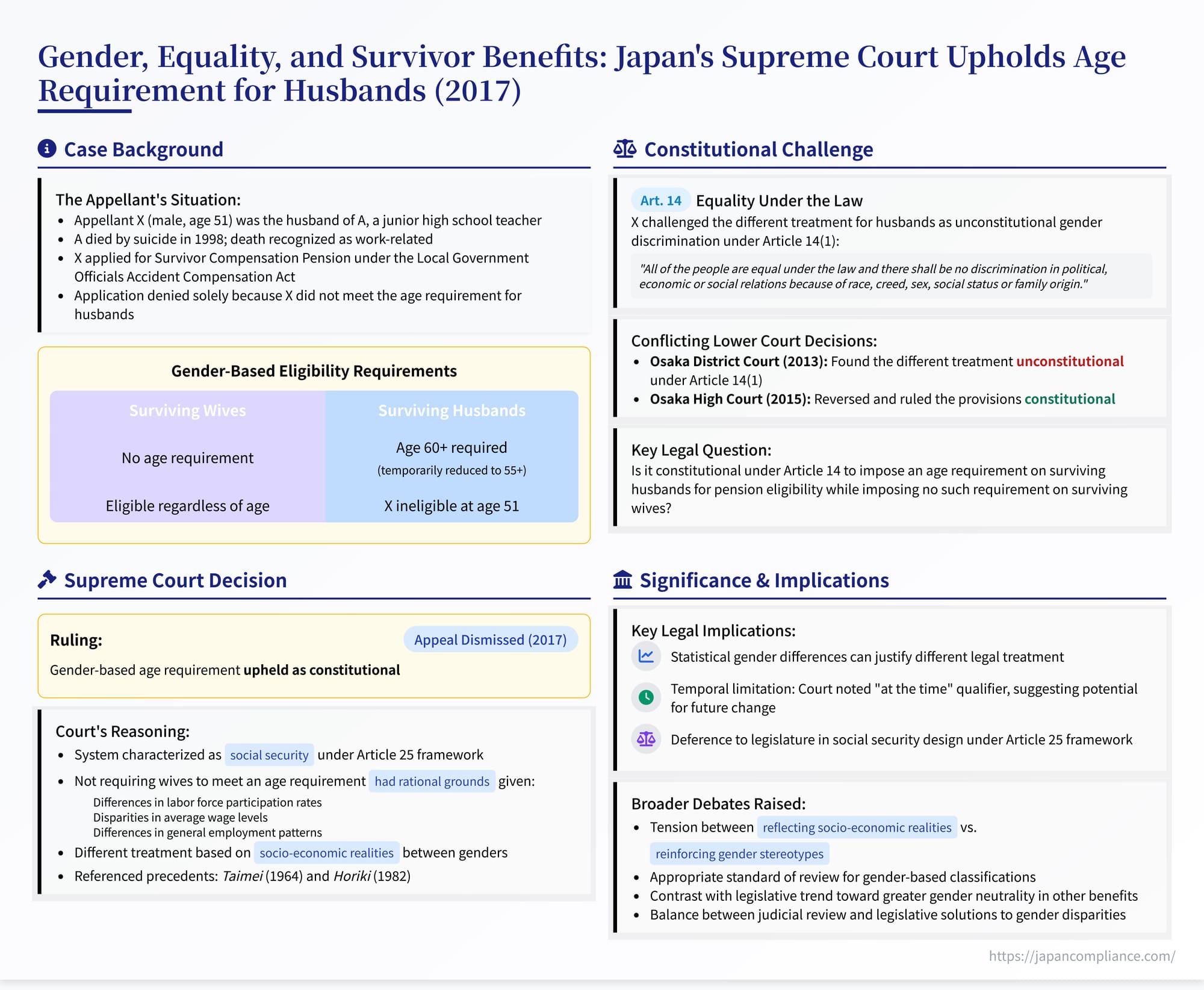

Japan’s Supreme Court (Mar 21 2017) upheld a Local Government Officials Accident Compensation Act rule that denies survivor pensions to husbands under 55, finding the gender‑based age threshold “not irrational” given labour‑market disparities. The Court applied a deferential Horiki‑style review under Article 14, leaving future change to the Diet.

Table of Contents

- Background: A Widower’s Claim for Survivor Benefits

- The Constitutional Challenge: Gender Equality under Article 14

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Age Requirement for Husbands Upheld

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

Laws establishing eligibility for social security benefits often involve classifications based on various criteria, including age, disability, income, and family relationships. When these classifications differentiate based on gender, they inevitably raise questions under constitutional guarantees of equality. A 2017 decision by Japan's Supreme Court directly confronted such a distinction within the survivor benefits scheme for local public employees, ultimately upholding a provision that imposed an age requirement on surviving husbands but not on surviving wives. This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Disposition Not to Grant Survivor Compensation Pension, etc. (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Heisei 27 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 375, March 21, 2017), offers important insights into how Japanese courts evaluate gender-based classifications in social security law against the principle of equality under Article 14 of the Constitution.

Background: A Widower's Claim for Survivor Benefits

The case involved X, the surviving husband of A, a public junior high school teacher in Japan. In 1998, A tragically died by suicide. Her death was subsequently recognized by the relevant authorities as being work-related – specifically, as resulting from a mental disorder caused by her official duties. This recognition potentially entitled her surviving family members to benefits under the Local Government Officials Accident Compensation Act (地方公務員災害補償法, Chihō Kōmuin Saigai Hoshō Hō, hereinafter "LGOCA").

X applied to the Local Government Officials Accident Compensation Fund (referred to as Y, the defendant/appellee) for a Survivor Compensation Pension (遺族補償年金, izoku hoshō nenkin) provided under the LGOCA. This pension is designed to provide long-term income support to eligible survivors of local public employees who die due to work-related causes.

However, the Fund (Y) denied X's application. The reason for denial was X's age: he was 51 years old at the time of A's death. The relevant provisions of the LGOCA established different eligibility requirements for surviving spouses based on gender:

- Surviving Wives: A surviving wife was eligible for the Survivor Compensation Pension regardless of her age at the time of her husband's death (provided other conditions like dependency were met).

- Surviving Husbands: A surviving husband, however, was generally required to be 60 years of age or older at the time of his wife's death to qualify (LGOCA Art. 32(1), proviso, item 1). A temporary supplementary provision (Suppl. Prov. Art. 7-2(2)) had lowered this age threshold to 55 for a certain period, but X, at 51, still did not meet this relaxed requirement. (Husbands could also qualify if they met specific disability criteria, regardless of age, under Art. 32(1), proviso, item 4, but this was not applicable to X).

Thus, solely because he was a husband under the age of 55, X was denied the survivor pension that a similarly situated wife would have automatically received. (His applications for related lump-sum benefits were also denied because eligibility for those was contingent on qualifying for the pension).

The Constitutional Challenge: Gender Equality under Article 14

X challenged the Fund's decision in court, arguing that the provisions of the LGOCA imposing an age requirement on husbands but not on wives constituted unconstitutional gender discrimination. His primary claim was that these provisions violated Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution of Japan, which states: "All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin."

The lower courts reached conflicting conclusions:

- Osaka District Court (November 2013): Found the different treatment based on gender to be unreasonable discrimination and ruled the relevant provisions of the LGOCA unconstitutional and invalid under Article 14(1). It revoked the Fund's non-支給 decision.

- Osaka High Court (June 2015): Reversed the District Court's decision. It held that the distinction between wives and husbands, based on the differing socio-economic circumstances generally faced by men and women at the time, was not unreasonable discrimination lacking rational basis. Therefore, the High Court concluded, the provisions did not violate Article 14(1). It dismissed X's claim.

X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Age Requirement for Husbands Upheld

The Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's ruling and upholding the constitutionality of the gender-based distinction in the LGOCA's survivor pension eligibility requirements.

The Court's reasoning was notably concise:

- Nature of the System (Link to Article 25): The Court began by characterizing the Survivor Compensation Pension system under the LGOCA as having the nature of social security, established to realize the purpose of Constitution Article 25 (right to minimum standards of living). This framing immediately invokes the line of precedent (like the Horiki case, explicitly cited later) establishing broad legislative discretion in designing social security systems.

- Justification for Different Treatment: The Court acknowledged that LGOCA Article 32(1) proviso imposes age requirements on survivors other than wives. It then directly addressed the core issue: the lack of an age requirement for wives versus the requirement for husbands. The Court's key finding was that not requiring wives to meet a certain age requirement was not lacking in rational grounds (gōri-teki na riyū o kaku mono to iu koto wa dekinai), even considering the circumstances at the time the denial decision was made regarding X.

- Basis for Rationality: Socio-Economic Differences: The Court explicitly grounded this rationality finding in its perception of the "social conditions wives were placed in" (tsuma no okarete iru shakai-teki jōkyō). It specifically pointed to societal differences between men and women concerning:

- Labor force participation rates within the working-age population.

- Average wage levels.

- General employment patterns.

The Court reasoned that these observed socio-economic disparities provided a rational basis for the legislature to treat surviving wives more favorably (by exempting them from the age requirement) compared to surviving husbands.

- Conclusion on Article 14(1): Since the preferential treatment of wives was deemed rational based on these societal differences, the Court concluded that the corresponding imposition of an age requirement on husbands could not be said to violate Article 14(1).

- Reliance on Precedent: The Court stated that this conclusion was evident when considering the principles laid down in key Grand Bench precedents: the 1964 Taimei decision (which established the general principle that equality under Article 14 allows for reasonable distinctions based on the nature of the matter) and the 1982 Horiki decision (which emphasized broad legislative discretion in social security under Article 25).

Thus, finding the High Court's judgment correct, the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal.

Significance and Analysis

This 2017 ruling is significant as a relatively recent Supreme Court affirmation of gender-based distinctions within a Japanese social security scheme. Its implications and the debates surrounding it include:

- Upholding Gender Classifications Based on Socio-Economic Averages: The core of the decision rests on the Court's acceptance of generalized socio-economic differences between men and women (labor participation, wages, employment patterns) as a rational basis for different legal treatment regarding survivor benefit eligibility. The Court essentially validated the legislative assumption that wives, on average, were more likely to be economically dependent or vulnerable following the death of a spouse compared to husbands, thus justifying the waiver of the age requirement for them.

- Standard of Review for Gender Discrimination: While citing the Horiki precedent (associated with broad legislative discretion and deferential review), the specific phrasing used – finding the distinction "not lacking in rational grounds" – might hint at a slightly different nuance compared to Horiki's language ("not unreasonable discrimination without rational basis"). Some commentary suggests this might represent a subtle shift or a reluctance to fully embrace the most deferential aspects of the Horiki standard when gender is the classifying factor. However, the outcome clearly reflects significant deference to the legislative judgment based on perceived societal realities. The Court did not explicitly engage with arguments often made in constitutional scholarship that gender classifications, as suspect categories, should trigger stricter scrutiny.

- Focus on Justifying Female Advantage: The Court framed its analysis primarily around justifying the absence of an age requirement for wives, rather than directly justifying the imposition of the requirement on husbands. By finding the preferential treatment of women rational based on their perceived societal circumstances, the differential treatment of men was deemed constitutionally acceptable as a corollary. This approach avoids directly confronting the argument that imposing the requirement solely on men is itself discriminatory.

- Reinforcing Stereotypes vs. Reflecting Reality?: The decision sparked considerable debate. Critics argue that relying on generalized socio-economic statistics to justify gender-specific legal rules risks reinforcing traditional gender roles and stereotypes (e.g., the male breadwinner model, female economic dependency). Such classifications may fail to account for the diverse realities of individual families, including households where the wife was the primary earner or where the husband faces significant economic hardship after the wife's death. There are concerns that such laws might hinder progress towards gender equality by embedding outdated assumptions into the legal framework. Conversely, defenders of the ruling might argue that it reflected socio-economic realities prevalent at the time the law was enacted (and potentially still relevant at the time of the decision) and represented a permissible legislative choice aimed at protecting a group perceived as more vulnerable on average.

- Temporal Limitation and Potential for Change: The Court notably qualified its finding by stating the distinction was rational "even at the time the non-支給処分 was made regarding the appellant." This temporal limitation explicitly leaves open the possibility that, as societal conditions regarding gender roles, labor participation, and economic standing evolve, the same distinction might cease to be rational and could potentially be found unconstitutional in the future. This acknowledges the dynamic nature of equality analysis and the potential for legal standards to adapt to changing social realities.

- Contrast with Legislative Trends: The ruling stands in some contrast to legislative trends in Japan that have moved towards greater gender neutrality in certain social security areas. For example, the Child Rearing Allowance and the basic survivor pension under the National Pension system (Surviving Child's Basic Pension) were extended to father-led single-parent households in the 2010s. Gender disparities in disability ratings for facial disfigurement under workers' compensation were also eliminated. However, as noted by commentators, gender distinctions remain in other areas, such as the widow's pension under the National Pension Act and survivor pensions under the Employees' Pension Insurance and the national public employees' compensation scheme, making this 2017 Supreme Court decision highly relevant to those ongoing legal structures.

- Focus on Legislative Solutions?: The Court's deferential stance implicitly places the onus on the legislature to address potentially outdated or inequitable gender distinctions through political processes rather than judicial intervention, unless the classification is deemed patently irrational. While some argue for stricter judicial review, others emphasize the need for legislative solutions that can consider the complex fiscal and social implications of modifying established systems.

Conclusion

The 2017 Supreme Court decision concerning the Local Government Officials Accident Compensation Act's Survivor Compensation Pension upheld the constitutionality of requiring surviving husbands, but not wives, to meet an age requirement for eligibility. Grounding its decision in the broad legislative discretion afforded in social security matters (under the umbrella of Article 25) and citing perceived socio-economic differences between men and women as a rational basis, the Court found that the gender-based distinction did not violate the equality guarantee of Article 14(1). While affirming the specific legal provision based on the circumstances considered relevant at the time, the ruling leaves the door open for future re-evaluation as societal conditions evolve and highlights the ongoing tension between traditional rationales for gender classification and the push for greater gender equality in Japanese law and society. The case underscores the judiciary's generally cautious approach to intervening in complex social security designs crafted by the legislature.

- Workers’ Comp vs. Consolation Money (1966): Supreme Court clarifies offset rules

- Statute of Limitations for Public vs. Private Monetary Claims: Matsudo City Hospital Case

- Mapping the Limits of Transparency: Supreme Court on Dam‑Site Information Disclosure

- Local Government Officials Accident Compensation Fund – Types of Benefits