Student Disability Pension Gap: Why Japan’s Supreme Court Backed Voluntary Enrollment (2007)

TL;DR

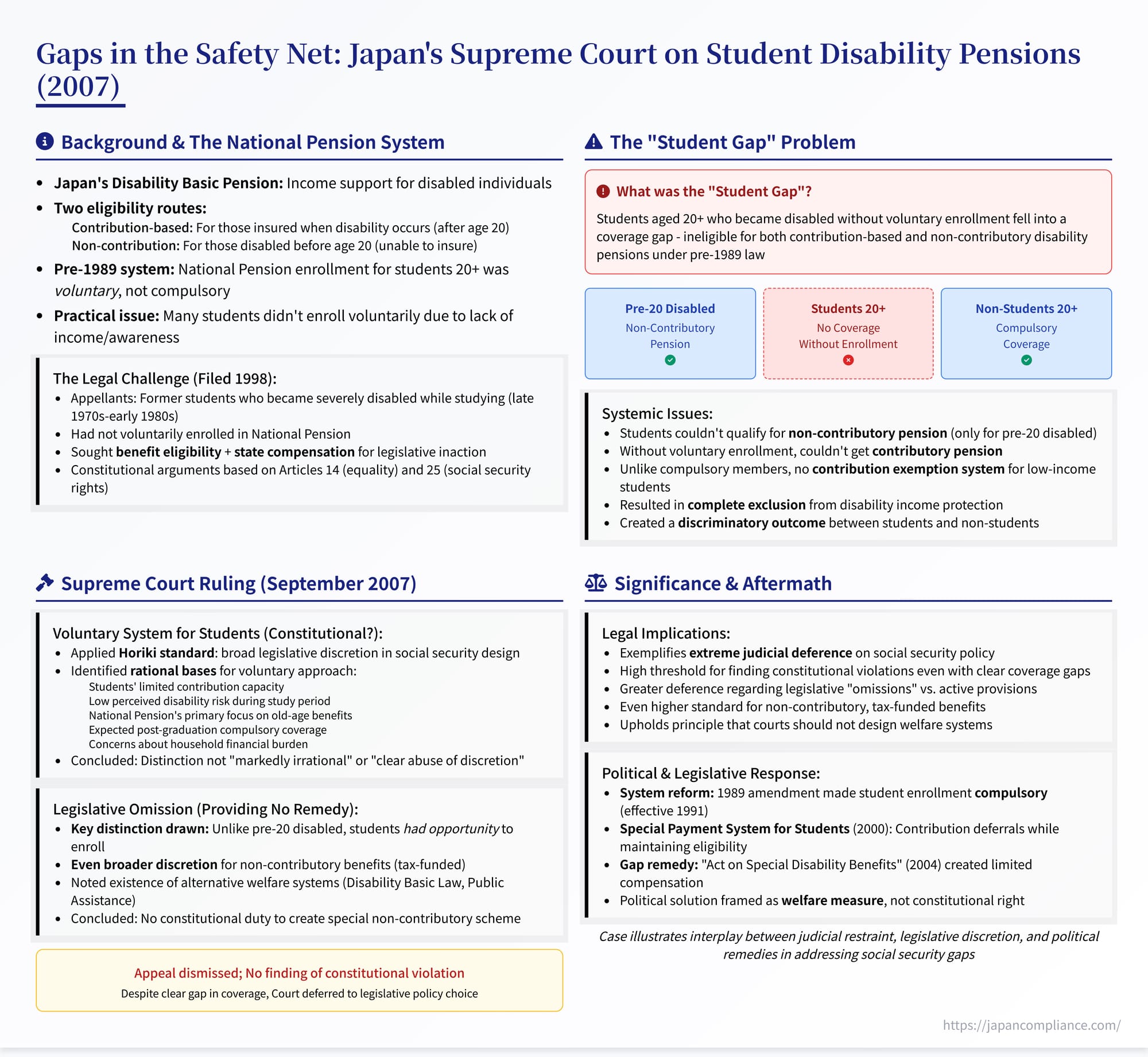

Japan’s Supreme Court (2007) upheld the constitutionality of the pre‑1989 National Pension framework that left some students disabled after age 20 without benefits. The Court applied an extremely deferential “markedly irrational” standard, ruled no violation of Articles 14 or 25 of the Constitution, and emphasized legislative discretion. Although the plaintiffs lost, political pressure prompted a 2004 statute creating a special, limited benefit to plug the historic gap.

Table of Contents

- Background: The National Pension System and the “Student Gap”

- The Legal Challenge by “Student Non‑Pensioners”

- Lower Court Rulings and the Path to the Supreme Court

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Deference to Legislative Discretion

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

Social security systems, designed to protect citizens against risks like old age, disability, and death, often involve complex rules about eligibility, contributions, and benefit levels. Sometimes, historical legislative choices or evolving societal structures can create unintended gaps, leaving certain groups without expected coverage. How the legal system addresses such gaps, particularly when fundamental rights like social security and equality are invoked, is a critical question. The Japanese Supreme Court's 2007 decision in the "Student Non-Pension Disability Case" (formally, Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Decision Not to Grant Disability Basic Pension, etc., Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, Heisei 17 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 246, Sept. 28, 2007) provides a stark example of this challenge. It addressed the plight of individuals who became severely disabled while students under an older pension system design that made their enrollment voluntary, ultimately finding the legislative framework constitutional despite the resulting lack of pension coverage for the appellants.

Background: The National Pension System and the "Student Gap"

Japan's public pension system provides a Disability Basic Pension (障害基礎年金, Shōgai Kiso Nenkin) to individuals who become disabled. There are two main routes to eligibility:

- Contribution-Based Pension: For individuals whose first medical consultation (shoshinbi) for the disabling condition occurs after they become insured under the National Pension (NP) system (typically at age 20). Eligibility generally requires being insured at the time of the shoshinbi and having a sufficient contribution history (though exemptions exist for low-income compulsory members).

- Non-Contribution-Based Pension: For individuals whose shoshinbi occurs before age 20. Since individuals under 20 cannot be insured under NP and pay contributions, the system provides a non-contributory pension funded by general revenue, acknowledging they had no opportunity to insure themselves against this risk.

The problem addressed in this case arose from the specific structure of the National Pension Act before amendments made in 1989 (effective 1991).

- Compulsory vs. Voluntary Enrollment: While residency in Japan generally meant compulsory NP enrollment from age 20 to 59, the pre-1989 law contained an exception for students enrolled in universities, high schools, etc. (excluding part-time or correspondence students). These students, aged 20 or over, were exempt from compulsory enrollment. Instead, they were offered voluntary enrollment (nin'i kanyū), meaning they could choose to join the NP system by applying to their prefectural governor and paying contributions.

- The Consequence: Many students, often lacking independent income and contribution capacity, did not voluntarily enroll. If such a student suffered a disabling injury or illness with a shoshinbi after turning 20 but while still unenrolled, they failed the primary requirement for the contribution-based Disability Basic Pension: being insured at the time of the shoshinbi. They were also ineligible for the non-contributory pension, as their shoshinbi was after age 20. This created a coverage gap – individuals disabled during their student years (after age 20) often received no disability pension.

- Contribution Exemption Issue: Furthermore, the system allowed compulsory insured individuals with low income to apply for contribution exemptions, which could still allow them to qualify for disability benefits under certain conditions. However, these exemption provisions explicitly did not apply to voluntary insured individuals. Voluntary members who failed to pay contributions simply lost their insured status.

The Legal Challenge by "Student Non-Pensioners"

The appellants in this case, X et al., were individuals who became severely disabled (equivalent to Grade 1 disability) while students between the late 1970s and early 1980s, under this pre-1989 legal framework. They had not voluntarily enrolled in the National Pension system.

In 1998, they applied for Disability Basic Pension benefits from their respective prefectural governors (Tokyo or Chiba). Their applications were denied on the grounds that they were not NP insured persons on the date of their first medical consultation (shoshinbi) because they had not voluntarily enrolled while students.

They subsequently filed lawsuits seeking:

- Revocation: Cancellation of the administrative decisions denying them benefits.

- State Compensation: Damages against the State (Government of Japan) based on the argument that the legislature's failure (omission) to enact appropriate measures to cover their situation constituted an illegal act under the State Compensation Act.

Their core constitutional arguments were:

- The pre-1989 legal framework itself – specifically the provisions exempting students 20+ from compulsory coverage and offering only voluntary enrollment (the "compulsory coverage exception provisions") – violated Article 14 (equality under the law) by unreasonably discriminating against students compared to other groups, and Article 25 (right to minimum standards of living) by failing to ensure adequate social security.

- The legislative omission – the failure of the Diet to provide a non-contributory disability pension scheme for students disabled after age 20 (analogous to the scheme for those disabled before 20) – also violated Articles 14 and 25.

Lower Court Rulings and the Path to the Supreme Court

The case saw differing outcomes in the lower courts, highlighting the contentious nature of the issue:

- Tokyo District Court (March 2004): This court denied the revocation claim, reasoning that it couldn't retroactively apply a specific remedy (like granting benefits) that was within the legislature's discretion to choose. However, it found a violation of Article 14 (Equality). It ruled that the difference in treatment created by the 1985 NP Act amendments (which formalized the non-contributory pension for the pre-20 disabled) between those disabled before 20 and students disabled after 20 (who remained uncovered if unenrolled) constituted unreasonable discrimination. It held the legislature had a duty to rectify this disparity and its failure to do so was illegal, awarding damages (¥5 million each) for this legislative omission. Other district courts in related lawsuits reached similar conclusions, sometimes focusing on the discrimination between students and non-student compulsory members.

- Tokyo High Court (March 2005): The High Court overturned the District Court's finding on damages. It ruled that the pre-1989 system, including the different treatment of students and the pre-20 disabled, did not violate Article 14. It upheld the denial of the revocation claim.

The appellants appealed the High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Deference to Legislative Discretion

The Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the appeal, affirming the Tokyo High Court's decision and finding no constitutional violation in the pre-1989 system's treatment of students.

1. Constitutionality of the Voluntary Enrollment System for Students (Pre-1989):

The Court first addressed the claim that exempting students aged 20+ from compulsory coverage and offering only voluntary enrollment was unconstitutional under Articles 25 and 14.

- Reiteration of the Horiki Standard: The Court started by citing the 1982 Horiki decision, reaffirming the principle that designing social security systems under Article 25 involves broad legislative discretion. Judicial review is limited to instances where the legislative choice is markedly lacking in rationality and constitutes a clear abuse or deviation from that discretion. While unreasonable discrimination can separately violate Article 14, the assessment occurs within this framework of legislative latitude.

- Rationale for Treating Students Differently: The Court then examined the justifications for the pre-1989 voluntary system for students. It found the legislature's choice was not markedly irrational or unreasonably discriminatory, based on a combination of factors considered plausible policy rationales at the time:

- Contribution Capacity: Students generally lack independent income and thus the capacity to pay insurance premiums.

- Low Disability Risk during Studies: The statistical probability of becoming severely disabled during the relatively short period of study after age 20 was considered low.

- Focus of NP & Value Proposition: The National Pension system's primary historical focus (and premium calculation basis) was on old-age and survivor benefits. The portion allocated to disability benefits was small. Therefore, compelling students to pay premiums mainly geared towards old-age benefits might not represent a worthwhile trade-off solely for disability coverage, especially given the low perceived risk.

- Post-Graduation Coverage: Most students were expected to enter the workforce after graduation and gain coverage through Employees' Pension Insurance or become compulsory NP members then.

- Household Burden: Compulsory enrollment could place a significant financial burden on parents or household heads (who are often legally obligated to ensure payment) if the student lacked income but the household did not qualify for exemptions based on the household head's income.

- Other Safety Nets: Existing systems like the Disability Basic Law (providing welfare services) and the Public Assistance Act (providing means-tested benefits) offered alternative forms of support for disabled individuals, including students.

- Conclusion on Voluntary System: Considering these factors, the Court concluded that the legislative decision to allow students the choice to enroll voluntarily, based on their individual circumstances and willingness/ability to pay, rather than imposing compulsory enrollment and the associated contribution burden (or complex exemption processes), was a policy decision within the Diet's broad discretion. The resulting "distinction in enrollment, etc." (kanyū tō ni kansuru kubetsu) between students and non-students (or regarding the applicability of contribution exemptions) was not deemed to be "unjust discriminatory treatment without any rational basis."

- Contribution Requirements: The Court further noted that relaxing contribution requirements for contribution-based benefits like the Disability Basic Pension is itself a matter of legislative discretion, closely tied to fiscal considerations. Thus, the fact that the voluntary system led to different outcomes based on enrollment and payment did not, in itself, render the system unconstitutional.

- Finding: Therefore, the pre-1989 measures concerning students (compulsory coverage exception, voluntary enrollment option, non-application of contribution exemptions to voluntary members) and the legislature's inaction in changing this system before 1989 did not violate Article 25 or Article 14(1).

2. Constitutionality of Legislative Omission (Failure to Provide Non-Contributory Pension):

The Court then addressed the argument that the legislature violated Articles 25 and 14 by failing to create a non-contributory Disability Basic Pension specifically for students disabled after age 20 who had not voluntarily enrolled.

- Nature of Non-Contributory Pensions: The Court characterized the existing non-contributory pension (for the pre-20 disabled) as supplementary (hokan-teki) to the primary contribution-based insurance system. It addresses situations where insurance principles cannot apply (i.e., disability arising before one could possibly contribute).

- Even Broader Discretion for Non-Contributory Schemes: Because non-contributory benefits are funded by general revenue and depend heavily on national and pension system finances, the Court held that the legislature possesses even broader discretion in deciding whether to establish such schemes, and determining their scope (eligibility, conditions), compared to its discretion regarding the contribution-based system.

- Key Distinction: Opportunity to Enroll: The Court drew a crucial distinction between the group receiving the non-contributory pension and the appellant students:

- Those disabled before age 20 were in a position where they absolutely could not become NP insured persons (compulsorily or voluntarily) before their disability arose.

- Students disabled after age 20, however, were given the opportunity to become insured through voluntary enrollment before their disability occurred.

- Relevance of Other Systems: The Court again mentioned the existence of other support systems (Disability Basic Law, Public Assistance) as relevant context.

- Conclusion on Omission: Given the broader legislative discretion regarding non-contributory benefits, the fact that students had an opportunity (even if voluntary) to secure coverage which the pre-20 disabled lacked, and the existence of other safety nets, the Court concluded that the legislature's decision not to create a special non-contributory pension for this specific group (students disabled post-20 without prior voluntary enrollment) was within the scope of legislative discretion and could not be deemed markedly lacking in rationality. The resulting difference in treatment between this group and the pre-20 disabled group was also not unreasonable or unjust discrimination violating Article 14.

- Finding: Therefore, the "legislative omission" (rippō fusakui) did not violate Article 25 or Article 14(1).

Based on these findings, the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal.

Significance and Analysis

The 2007 Student Non-Pension Disability decision is a significant, and controversial, ruling in Japanese social security and constitutional law.

- Reinforcement of Extreme Judicial Deference: The judgment represents a high-water mark for judicial deference to legislative discretion in the social security field. By upholding a system that demonstrably left a vulnerable group without core disability income protection, the Court signaled an extremely high bar for challenging legislative choices or omissions based on Article 25 or Article 14. The standard of "markedly lacking in rationality" and "clear abuse of discretion" (Horiki standard) proved very difficult to meet.

- Justification of Differential Treatment: The Court accepted the government's justifications for treating students differently under the pre-1989 system. Critics, however, questioned the realism of these justifications. For instance, was the "opportunity" for voluntary enrollment truly meaningful for students without financial means? Was the probability of disability genuinely negligible enough to justify the lack of compulsory coverage? Was reliance on the means-tested Public Assistance system an adequate substitute for an earned disability pension right? The lower court decisions finding Article 14 violations suggest these points were highly contested.

- Legislative Omission and Judicial Review: The ruling suggests potentially even greater judicial restraint when reviewing alleged "legislative omissions" compared to reviewing existing legislative classifications, especially concerning non-contributory, tax-funded benefits where fiscal discretion is paramount.

- Political Remedy vs. Constitutional Right: While the legal challenge ultimately failed at the Supreme Court level, the series of lawsuits brought significant public attention to the plight of student non-pensioners. This political pressure contributed to a legislative solution. Following the initial District Court ruling in this case (which had found an Article 14 violation), the Diet enacted the "Act on Provision of Special Disability Benefit to Specific Persons with Disabilities" (特定障害者に対する特別障害給付金の支給に関する法律) in 2004 (effective 2005). This law created a special, non-contributory benefit funded by general revenue for individuals (including former students and some spouses who were also previously excluded) who were left without pension coverage due to the pre-reform voluntary enrollment system. Importantly, this was framed as a welfare measure based on political considerations regarding the pension system's historical development, not as a recognition of a pre-existing constitutional entitlement as determined by the courts. The benefit amount is also lower than the standard Disability Basic Pension.

- Current System: The underlying systemic issue was resolved by the 1989 legislative reform (effective 1991) which made National Pension enrollment compulsory for students aged 20 and over. Further refinements, like the "Special Payment System for Students" (学生納付特例制度, introduced in 2000), allow students with low income to apply for deferral of their contributions while maintaining eligibility for disability benefits should the need arise, addressing the contribution capacity issue within a compulsory framework.

Conclusion

The 2007 Supreme Court decision in the Student Non-Pension Disability Case ultimately upheld the constitutionality of the pre-1989 National Pension system's voluntary enrollment provision for students. The Court applied a highly deferential standard of review, finding that the legislative choices made at the time, and the failure to provide a specific non-contributory benefit for this group, fell within the broad legislative discretion afforded under the Constitution and did not constitute unreasonable discrimination under Article 14. While the legal claims failed, the associated litigation played a crucial role in highlighting a significant gap in the social safety net, eventually leading to a specific, albeit limited, legislative remedy through the Special Disability Benefit system. The case stands as a powerful illustration of the interplay between judicial review, legislative discretion, and political solutions in shaping social security rights and addressing systemic coverage gaps in Japan.

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- The Witness as Evidence: How Japan's High Court Ruled on the Crime of Hiding a Witness

- Overview of Japan’s Public Pension System – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare