Future Price Not a "Material Particular" for Non-Disclosure Cancellation: Japan's Supreme Court on Gold Futures and Consumer Contracts

Judgment Date: March 30, 2010

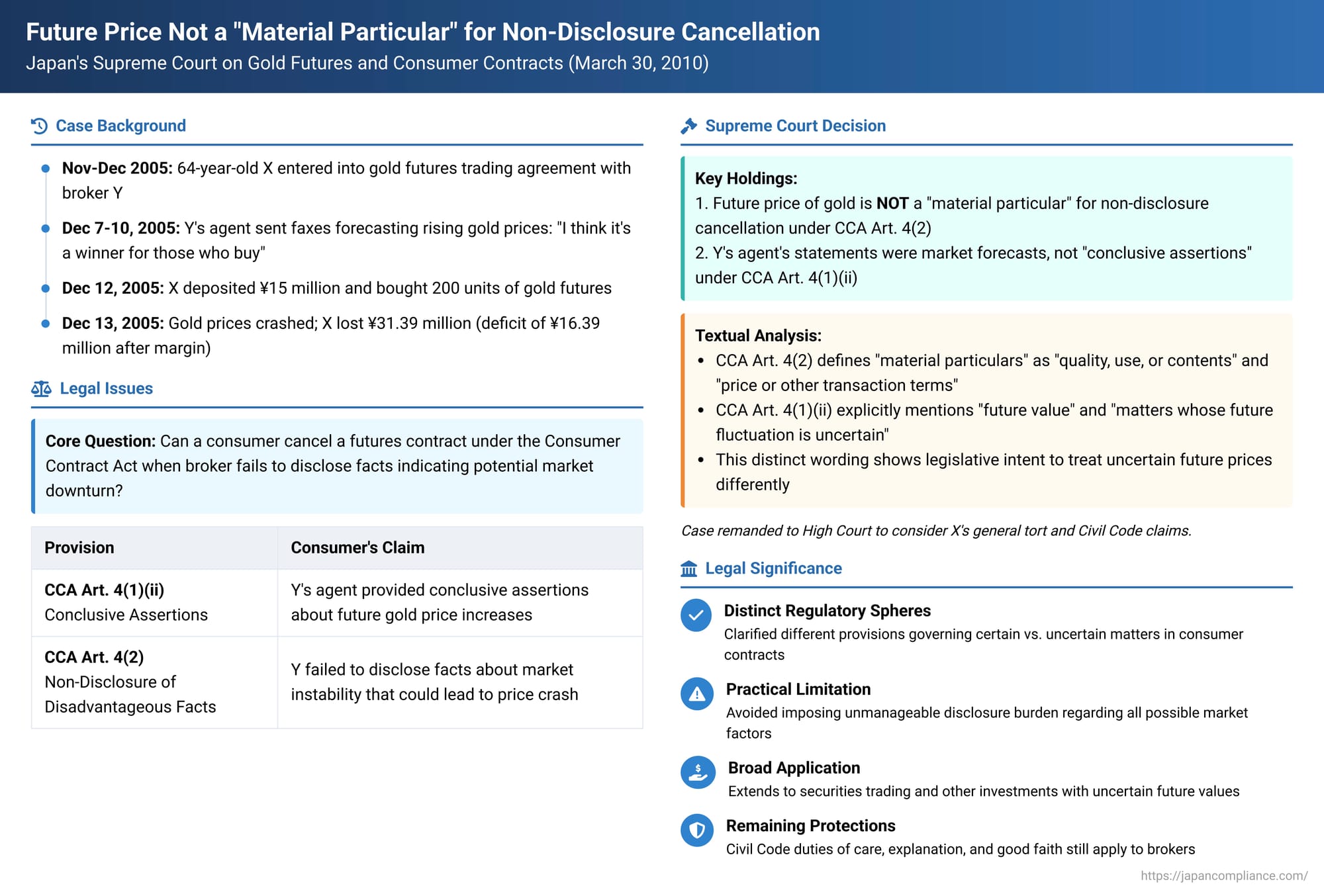

Commodity futures trading is an inherently risky endeavor, with the potential for substantial profits or devastating losses based on volatile price movements. When consumers engage in such transactions, what level of disclosure can they expect from their brokers regarding potential future price changes? And if a broker paints an overly optimistic picture, or fails to highlight downside risks, can the consumer later cancel the contract under Japan's Consumer Contract Act (CCA)? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed these critical questions in a judgment on March 30, 2010 (Heisei 20 (Ju) No. 909), which reviewed a Sapporo High Court decision concerning a gold futures contract. The ruling provided significant clarification on the scope of "material particulars" (重要事項 - jūyō jikō) for the purpose of non-disclosure under the CCA.

The Gold Futures Venture: High Hopes, Then a Steep Fall

The plaintiff, X, a 64-year-old company representative at the time, was solicited by an agent of Y, a commodity futures brokerage firm. After receiving explanations about the mechanisms of futures trading and the inherent risks associated with market fluctuations, X submitted an acknowledgment on November 24, 2005, affirming that he would trade based on his own judgment and responsibility. On the same day, X entered into a basic agreement with Y to engage in commodity futures trading.

Subsequently, on December 7 and 10, 2005, Y's agent sent faxes to X. These communications conveyed the agent's own market forecast that gold prices on the Tokyo market were on an upward trend and that this trend was likely to continue through the end of the year. The faxes included encouraging expressions such as, "I think it's a winner for those who buy," effectively suggesting that purchasing gold futures would lead to profits. Based on these solicitations, X decided to act.

On December 12, 2005, pursuant to the basic agreement, X deposited ¥15 million with Y as trading margin (委託証拠金 - itaku shōkokin) and placed a buy order for 200 units of gold futures. This transaction constituted the specific contract (hereinafter "the Contract") at the heart of the dispute. The buy order was executed later that day.

The market, however, had other plans. While gold prices on the Tokyo market had indeed been soaring up to the point of the Contract, they experienced a sharp crash on the very next day, December 13, 2005. X promptly moved to close out his position but still incurred a substantial loss of ¥31.39 million. After Y applied X's ¥15 million margin to this loss, a shortfall of ¥16.39 million remained, which Y paid to the Tokyo Commodity Exchange (TOCOM) on X's behalf.

This led to two intertwined lawsuits: X sued Y to recover his ¥15 million margin plus attorney fees, alleging illegal solicitation (primarily in tort). Y, in turn, sued X for reimbursement of the ¥16.39 million it had advanced. The Sapporo District Court initially dismissed X's claim and granted Y's claim.

The Consumer Contract Act Claims Take Center Stage on Appeal

X appealed to the Sapporo High Court. In addition to re-asserting his initial claims (now as preliminary claims) and adding an alternative claim for damages due to breach of Y's duty of sincerity and fairness as a broker, X introduced a primary argument: the cancellation of the Contract under the Consumer Contract Act (CCA), seeking the return of his ¥15 million margin on the grounds of unjust enrichment. This CCA-based cancellation claim rested on two specific provisions:

- CCA Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 2: Alleging that Y's agent had provided "conclusive assertions" (断定的判断の提供 - danteiteki handan no teikyō) about future gold price increases, which are matters whose future fluctuation is uncertain.

- CCA Article 4, Paragraph 2: Alleging that Y's agent, while telling X that investing would be advantageous, had intentionally failed to disclose "disadvantageous facts" (不利益事実の不告知 - furieki jijitsu no fukokuchi) concerning a "material particular" (重要事項 - jūyō jikō) – namely, the future price of gold. X argued that this non-disclosure led him to mistakenly believe that such disadvantageous facts did not exist. The specific undisclosed disadvantageous facts cited by X included the then-extreme divergence between Tokyo gold prices and international benchmark prices, and the fact that TOCOM was reportedly considering implementing temporary additional margin requirements due to this market volatility.

The Sapporo High Court (in its judgment of January 25, 2008, which was the subject of the Supreme Court review) rejected X's claim based on "conclusive assertions," finding that Y's agent's statements were market forecasts rather than guarantees of certain profit. However, the High Court upheld X's claim for cancellation based on "non-disclosure of disadvantageous facts." It reasoned that in commodity futures trading, where the goal is to profit from price changes, the "future price of gold" constitutes a "quality of the object of the transaction" (as per the definition of material particulars in CCA Art. 4, Par. 4, Item 1, now Art. 4, Par. 5, Item 1) and is a matter that would "normally affect a consumer's judgment whether to conclude the contract." Therefore, the High Court deemed the future price of gold a "material particular" under CCA Art. 4, Par. 2, and found that Y's failure to disclose the cited disadvantageous facts warranted cancellation. Y Insurance Company appealed this part of the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Interpretation: Distinguishing "Conclusive Assertions" from "Non-Disclosure of Material Particulars" Regarding Future Prices

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated March 30, 2010, partially overturned the Sapporo High Court's ruling. Specifically, it reversed the High Court's finding that allowed X to cancel the Contract under CCA Article 4, Paragraph 2 due to non-disclosure of disadvantageous facts about the future price of gold.

The Supreme Court's reasoning hinged on a careful textual analysis and comparison of the relevant provisions within CCA Article 4:

- Defining "Material Particulars" for Non-Disclosure (Art. 4, Par. 2): The Court noted that CCA Article 4, Paragraph 2 (which allows cancellation for non-disclosure of disadvantageous facts) defines "material particulars" by referencing Article 4, Paragraph 4 (now Art. 4, Par. 5). This definition encompasses:

- "Quality, use, or other contents" of the object of the consumer contract (e.g., the features of a product).

- Its "price or other transaction terms" (e.g., the cost of the product, payment conditions).

The Supreme Court found that the wording of this definition does not explicitly or implicitly include "matters whose future fluctuation is uncertain," such as the future price of a commodity in a futures contract.

- Contrasting with "Conclusive Assertions" (Art. 4, Par. 1, Item 2): The Court drew a sharp contrast with CCA Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 2. This provision, which allows cancellation if a business provides "conclusive assertions" about uncertain matters, explicitly lists as examples "its future value, the amount the consumer should receive in the future, or other matters whose future fluctuation is uncertain."

- The Consequence of the Distinction: Based on this textual difference, the Supreme Court concluded that in the context of X's gold futures contract, the future price of gold does not constitute a "material particular" for the purposes of CCA Article 4, Paragraph 2. Therefore, Y's failure to inform X about facts that might indicate a potential future crash in gold prices did not give X the right to cancel the Contract under this non-disclosure provision.

The Supreme Court also concurred with the lower courts' finding that Y's agent had not provided "conclusive assertions" about future gold prices that would trigger cancellation under CCA Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 2. Y's statements were characterized as optimistic market forecasts rather than guarantees of certain profit.

With both CCA-based cancellation routes thus closed, the Supreme Court remanded the case back to the Sapporo High Court. This was for the High Court to re-examine X's remaining (preliminary) claims, which were based on general tort law (illegal solicitation) or breach of contractual duties under the Civil Code (such as the duty of care or loyalty expected of a broker), rather than specific cancellation rights under the Consumer Contract Act.

Analyzing the Ruling: Scope, Rationale, and Implications

The Supreme Court's decision effectively delineates the distinct regulatory spheres of CCA Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 2 (conclusive assertions) and Article 4, Paragraph 2 (non-disclosure of disadvantageous facts) when it comes to matters of uncertain future value, particularly prices in speculative markets.

- Primary Regulation via "Conclusive Assertions": For issues concerning the uncertain future price or value of an investment, the primary consumer protection mechanism under the CCA is the prohibition against providing "conclusive assertions" (Art. 4(1)(ii)). If a broker guarantees future profits or asserts with certainty that a price will rise, that could be grounds for cancellation.

- "Future Price" Not a "Material Particular" for Non-Disclosure: The future price itself, being inherently uncertain, is not considered a "material particular" about which disadvantageous facts must be disclosed under Art. 4(2) to avoid cancellation under that specific provision.

This interpretation has broad implications for a wide range of transactions involving fluctuating future values, extending beyond commodity futures to include securities trading and potentially even real estate transactions where future market appreciation is a significant, albeit uncertain, factor for buyers.

Legal commentators suggest a strong practical rationale may underlie this distinction. If "future price" were deemed a "material particular" for the purpose of non-disclosure under Art. 4(2), then any broker offering a positive market forecast (even one not rising to the level of a "conclusive assertion") might find themselves under an obligation to disclose every conceivable factor that could negatively influence future prices. Such a requirement could become unmanageably broad and might effectively stifle any form of market prediction or advisory communication, which can be valuable to investors when presented responsibly.

It is crucial to understand that the Supreme Court's ruling is specific to fluctuating future prices in the context of CCA Art. 4(2). It does not necessarily signal a general retreat from a broader, consumer-protective interpretation of "material particulars" in other contexts. For instance:

- Misrepresentations about the current price or quality of a product would still fall under "material particulars."

- Failure to disclose existing defects in a product would likely still be a non-disclosure regarding a "material particular."

- Even certain knowable future facts (that are not mere price speculations), such as a definite plan for a construction project that will obstruct the view from a purchased apartment, could potentially be considered related to the "quality" or "contents" of the contract's object and thus a "material particular."

Beyond CCA Cancellation: The Enduring Role of General Civil Code Duties

The Supreme Court's decision that CCA-based cancellation was not available to X for non-disclosure of future price risks does not mean that brokers like Y are free from all responsibility regarding their solicitations and advice. The Court specifically remanded the case for re-examination of X's claims under general Civil Code principles.

Under these broader principles:

- A broker could still be found liable in tort if their solicitation methods were illegal, overly aggressive, or misleading in a way that caused harm.

- A broker could be found liable for breach of contractual duties (arising from the basic agreement to provide brokerage services) if they failed to exercise the proper duty of care, loyalty, or explanation expected of a professional in their position, particularly considering the investor's experience, financial situation, and investment objectives. This duty to explain risks can arise from the principle of good faith and fair dealing.

Any damages awarded under these general Civil Code claims might also be subject to reduction based on the investor's own comparative negligence, considering X's experience and his acknowledgment of trading at his own risk. Indeed, legal commentary notes that even after this Supreme Court decision, other similar cases have resulted in brokers being held liable in tort for damages caused by improper solicitation practices related to futures price movements.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 2010 judgment in the gold futures case provides a critical interpretation of the Consumer Contract Act concerning transactions involving uncertain future prices. It narrowly defines "material particulars" for the purpose of non-disclosure under CCA Article 4, Paragraph 2, effectively excluding inherently fluctuating future prices from its direct scope. Such issues are, within the CCA's framework, primarily addressed by the prohibition on "conclusive assertions" under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 2. However, the ruling also implicitly reaffirms that commodity brokers remain subject to general duties of care, fair dealing, and adequate explanation under the Civil Code, which can form the basis for damage claims even when specific CCA cancellation rights are not applicable. This decision highlights the distinct but complementary roles of specific consumer protection statutes and broader civil law principles in regulating complex financial transactions.