Japan’s Supreme Court Clarifies Hit‑and‑Run Relief: Future Disability Pensions Must Offset Government Compensation (2009)

Japan’s Supreme Court held that future Workers’ Comp disability pensions must be fully deducted from state hit‑and‑run compensation, reshaping victim relief rules.

TL;DR

The 2009 Supreme Court ruled that, when the government compensates hit‑and‑run victims under the Automobile Liability Security Act, it must deduct the full present value of any future Workers’ Accident Compensation disability pension—treating the scheme as a supplementary social‑security measure rather than a tort‑like damages award.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Hit‑and‑Run Accident, Severe Injury, and Overlapping Benefits

- Legal Framework: Government Compensation and Coordination with Other Benefits

- Lower Court Rulings: Deduction Limited to Past Benefits

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (December 17 2009 – Majority Opinion)

- The Dissenting Opinion

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

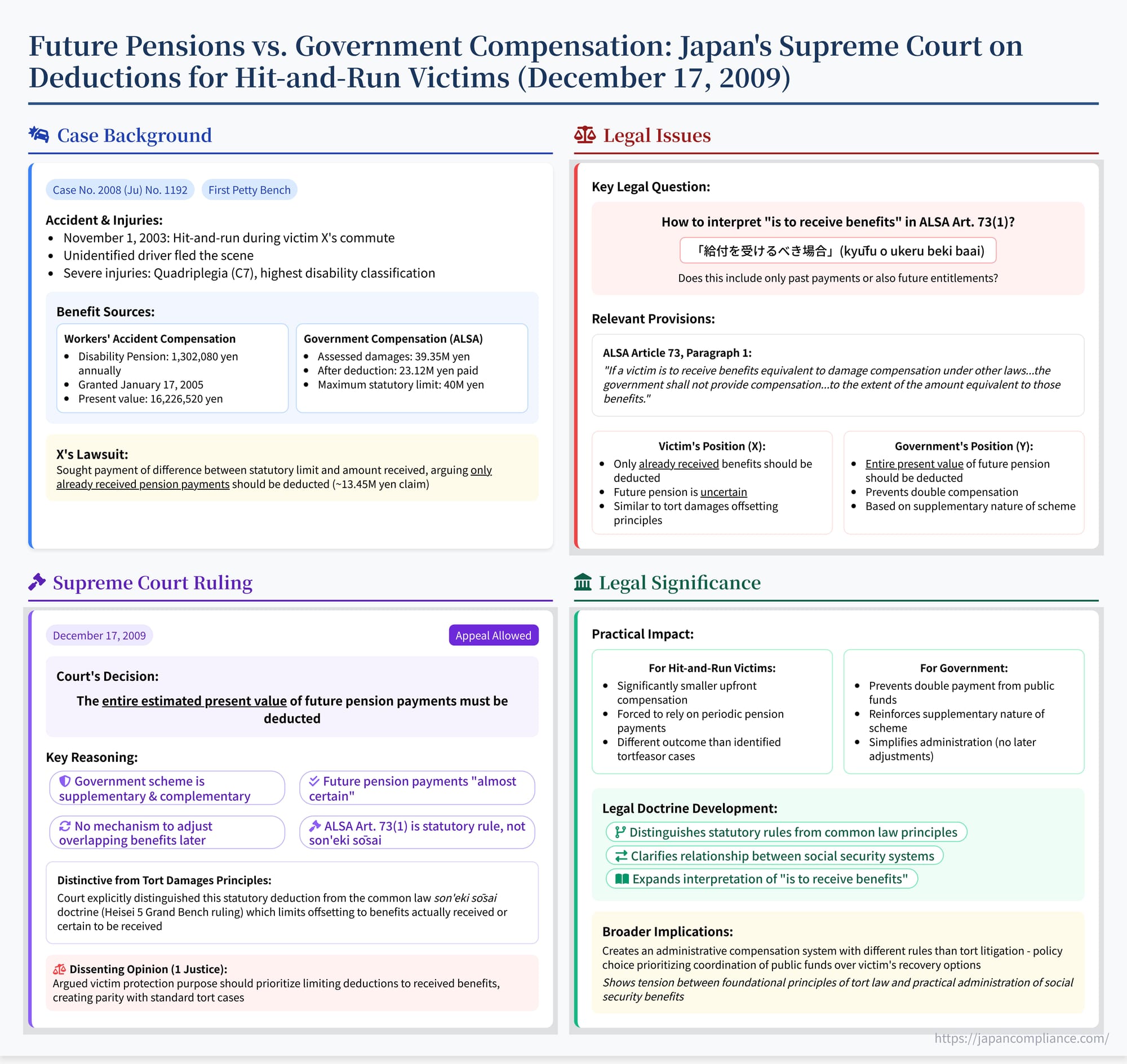

On December 17, 2009, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a judgment addressing a complex issue at the intersection of social security and victim compensation under the Automobile Liability Security Act (ALSA, or Jidōsha Songai Baishō Hoshō Hō - 自賠法) (Case No. 2008 (Ju) No. 1192, "Damage Compensation Claim Case"). The case focused on the government-operated Automobile Liability Security Business (保障事業 - hoshō jigyō), a scheme designed to compensate victims of hit-and-run accidents or accidents caused by uninsured vehicles. Specifically, the Court determined the extent to which future payments from other social security systems, such as disability pensions under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act, or Rōsai Hoken Hō - 労災保険法), should be deducted from the compensation provided by the government scheme. The Court concluded that the entire estimated present value of future pension benefits must be deducted, distinguishing this statutory adjustment from the general principles of offsetting gains and losses (son'eki sōsai) applied in standard tort litigation.

Factual Background: Hit-and-Run Accident, Severe Injury, and Overlapping Benefits

The case involved a victim severely injured in a hit-and-run accident who was eligible for benefits from multiple sources:

- The Accident: On November 1, 2003, the appellee, X, was injured in a traffic accident while commuting. The collision involved another vehicle that subsequently fled the scene and remained unidentified.

- Severe Injuries: X suffered catastrophic injuries, including cervical spine fracture, spinal cord injury, and traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. These resulted in permanent quadriplegia below the C7 level, bladder and rectal dysfunction, and spinal deformity. These injuries qualified X for the highest level of permanent disability under the ALSA enforcement ordinance (Schedule 1, Class 1, Item 1). X's total damages resulting from these injuries exceeded the statutory maximum compensation limit under the government's hoshō jigyō, which was 40 million yen at the time.

- Workers' Compensation Disability Pension: Because the accident occurred during X's commute, it qualified as a work-related (commuting) accident under the WCAI Act. Due to the permanent disability resulting from the accident, X became entitled to a Disability Pension (shōgai nenkin) under the WCAI Act. A decision granting this pension (at an annual rate of 1,302,080 yen) was issued on January 17, 2005. The calculated present value of the total amount X was expected to receive from this pension over their average remaining life expectancy was 16,226,520 yen.

- Government Compensation Claim (Hoshō Jigyō): Since the party responsible for the accident was unidentified (a hit-and-run), X could not claim damages directly from the tortfeasor or their Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance (CALI, jibaiseki). Instead, X applied to the government (appellant Y) for compensation under the Automobile Liability Security Business (hoshō jigyō) provided for in ALSA Article 72, Paragraph 1, first sentence. This provision establishes a government fund to compensate victims in such situations. X submitted this claim on February 25, 2005.

- Government Payment and Deduction Dispute: The government (Y) assessed X's damages at 39.35 million yen (slightly below the 40 million yen limit). Crucially, Y then deducted the entire estimated present value of X's future WCAI disability pension entitlement (16,226,520 yen) from this amount. On July 19, 2005, Y paid X only the remainder, 23,123,480 yen.

- X's Lawsuit: X disputed the deduction of the future pension benefits, arguing that only the amounts actually received by the time of the court's decision should be deducted. X sued Y (the government) seeking payment of the difference between the statutory limit (40M yen) and the amounts already paid by Y (23.12M yen) and received by X from the WCAI pension up to the close of the High Court's oral arguments (which amounted to 3,425,260 yen). X thus claimed approximately 13.45 million yen plus delay damages. (Note: The judgment mentions X temporarily lost the disability pension and received an injury/sickness pension during periods of relapse but regained the disability pension right afterward; this temporary switch didn't fundamentally alter the legal issue regarding the deduction of the ongoing pension entitlement).

Legal Framework: Government Compensation and Coordination with Other Benefits

The case turned on the interpretation of ALSA Article 73, Paragraph 1, which governs the coordination between the government's hoshō jigyō compensation and benefits received under other laws:

- ALSA Article 72(1): Establishes the government's duty to provide compensation (songai no tenpo) to victims of hit-and-run or uninsured vehicle accidents, up to limits specified by cabinet order.

- ALSA Article 73(1): Stipulates that if the victim "is to receive benefits... equivalent to the compensation for damage" under other specified laws (including the Health Insurance Act, WCAI Act, and others designated by cabinet order), the government shall "not provide compensation under [Art. 72(1)] to the extent of the amount equivalent to those benefits."

The central question was how to interpret "is to receive benefits" (kyūfu o ukeru beki baai) in the context of periodic payments like disability pensions. Does it refer only to past, accrued payments, or does it encompass the entire stream of future payments the victim is entitled to receive?

Lower Court Rulings: Deduction Limited to Past Benefits

The High Court, affirming the first instance court, ruled in favor of X. It interpreted ALSA Article 73(1) narrowly, focusing on the phrase "is to receive benefits" and the victim-protection purpose of ALSA. It held that:

- Deducting future benefits is permissible only when receipt of those future benefits is certain.

- Future disability pension payments are inherently uncertain due to potential changes in eligibility criteria, benefit amounts, or the recipient's right terminating early (e.g., due to recovery or death, or temporary switches to other benefits as occurred in X's case).

- Therefore, only pension installments already received or definitively determined to be payable by the close of oral arguments met the necessary certainty threshold.

- Consequently, Y should have deducted only the ~3.43 million yen X had actually received from the WCAI pension by the trial's end, not the estimated ~16.23 million yen representing future payments.

The government (Y) appealed this interpretation to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (December 17, 2009 - Majority Opinion)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated December 17, 2009, overturned the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of the government (Y), holding that the entire estimated present value of future disability pension payments must be deducted under ALSA Article 73(1).

1. Purpose and Nature of the Government Security Business (Hoshō Jigyō):

The Court began by characterizing the hoshō jigyō. It emphasized that this government compensation is not equivalent to standard tort damages or CALI insurance payments. Instead, it is a social security measure designed as a safety net for victims who cannot obtain relief through the primary liability insurance system. Its purpose is victim relief from a social policy standpoint. Consequently, the Court reasoned, the hoshō jigyō is intended to be "complementary and supplementary" (hokanteki, hojūtekina) to benefits available from other sources, including social insurance systems like the WCAI.

2. Interpretation of ALSA Article 73(1) - "is to receive benefits":

Based on this supplementary nature, the Court interpreted the phrase "is to receive benefits" (ukeru beki baai) in Article 73(1) broadly. It concluded that this phrase refers to the victim's entire entitlement under the other law, encompassing not only past payments but also the stream of future payments the victim is expected to receive based on their established pension right.

3. Lack of Alternative Adjustment Mechanism:

A key factor in the Court's reasoning was the absence of any statutory mechanism within ALSA or related laws to prevent double recovery if the government hoshō jigyō pays first without deducting future benefits, and the victim later receives those same benefits from, for example, WCAI. The Court noted that while some systems have rules for adjusting later payments (e.g., reducing future WCAI benefits if tort damages were received first, per WCAI Act Art. 12-4), no corresponding rule exists to reclaim hoshō jigyō payments or reduce future WCAI payments if the hoshō jigyō payment failed to account for future WCAI entitlement. Given the supplementary purpose of the hoshō jigyō, this lack of a clawback or later adjustment mechanism strongly suggested that the initial calculation under Art. 73(1) must deduct the entire expected value of the other benefit to prevent potential overlaps.

4. Assessment of Future Pension Certainty:

The Court addressed the lower court's concern about the uncertainty of future pension payments. It acknowledged potential fluctuations but considered the payment of WCAI disability pensions to be "almost certain" (hobo kakujitsu) as long as the qualifying disability persists (citing WCAI Act Art. 9). It viewed termination events as limited (e.g., death, recovery reducing disability below threshold) or involving substitution with equivalent benefits (like the temporary switch to an injury/sickness pension in X's case). Therefore, the Court concluded that deducting the estimated present value of future payments based on actuarial assumptions (like average life expectancy) does not impose an undue disadvantage on the victim.

5. Distinction from Son'eki Sōsai Doctrine (Heisei 5 Grand Bench Ruling):

Crucially, the Court explicitly distinguished the statutory adjustment under ALSA Article 73(1) from the common law doctrine of son'eki sōsai (offsetting gains and losses) as applied in tort damages between private parties. The Court referenced its own Heisei 5 (1993) Grand Bench decision (analyzed in the previous request), which held that for son'eki sōsai in tort damages, only benefits actually received or whose payment is certain to a degree equivalent to receipt can be offset.

The Court stated that ALSA Art. 73(1) is not an application of the son'eki sōsai doctrine. Rather, it is a specific statutory rule governing the coordination between the government's special compensation scheme and other public benefits. Therefore, the "certainty" standard established in the Heisei 5 decision for son'eki sōsai does not apply to the interpretation of ALSA Art. 73(1). The specific statutory language and purpose of Art. 73(1), particularly the supplementary nature of the hoshō jigyō and the lack of other adjustment rules, mandate the deduction of the full estimated value of future benefits.

Conclusion: Based on this reasoning, the government (Y) was correct in deducting the entire estimated present value of X's future WCAI disability pension (~16.23M yen) when calculating the hoshō jigyō payment. The lower courts erred in limiting the deduction to only past payments.

The Dissenting Opinion

One Justice dissented, arguing that the lower courts' interpretation limiting the deduction to past/certain payments was correct.

- The dissent emphasized the primary victim protection purpose of ALSA, suggesting the hoshō jigyō should aim for compensation levels equivalent to those under standard CALI insurance.

- It argued that in standard tort/CALI cases, future social insurance benefits like WCAI pensions are generally not deducted upfront from lump-sum damage awards (citing a Showa 52 [1977] precedent). The majority's interpretation creates an unfair disparity for victims solely based on whether the tortfeasor is identifiable/insured.

- It viewed the majority's reliance on the lack of adjustment mechanisms as filling a legislative gap in a manner detrimental to victims. It suggested other adjustment rules (like WCAI Act Art. 12-4(2)) might be applicable by analogy if needed later.

- It criticized the outcome as effectively forcing hit-and-run victims eligible for pensions into accepting periodic payments (via the pension) instead of the lump-sum compensation potentially available through CALI or standard tort claims.

Implications and Significance

This 2009 Supreme Court decision has significant practical consequences for victims compensated under Japan's government Automobile Liability Security Business (hoshō jigyō):

- Full Deduction of Future Pensions: It mandates the deduction of the entire estimated present value of future periodic benefits (like WCAI disability pensions) from the compensation paid by the government scheme under ALSA Art. 73(1).

- Different Treatment for Hoshō Jigyō Victims: This creates a notable difference in outcomes. Victims compensated through the hoshō jigyō receive significantly less upfront compensation compared to victims who can claim against an identified, insured tortfeasor, where future periodic benefits are generally not deducted from the lump-sum tort damages award based on the son'eki sōsai principles affirmed in the Heisei 5 (1993) Grand Bench decision.

- Prioritization of Public Funds Coordination: The ruling prioritizes the supplementary nature of the hoshō jigyō and the prevention of potential double payments from different public or quasi-public sources (WCAI and the hoshō jigyō fund) over maintaining parity with standard tort compensation principles.

- Clarification of ALSA Art. 73(1) vs. Son'eki Sōsai: It clearly distinguishes the specific statutory adjustment mechanism of ALSA Art. 73(1) from the general common law doctrine of son'eki sōsai, holding that the stricter "certainty" requirement for offsetting future benefits developed for the latter does not apply to the former.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 17, 2009, decision established that under Article 73, Paragraph 1 of Japan's Automobile Liability Security Act, the government, when providing compensation through its Security Business (hoshō jigyō) for hit-and-run or uninsured accidents, must deduct the full estimated present value of future periodic benefits (such as WCAI disability pensions) that the victim is entitled to receive due to the same accident. This interpretation, based on the supplementary nature of the government scheme and the lack of other adjustment mechanisms, mandates a broader deduction than typically applied under the general tort law principle of son'eki sōsai, resulting in different net compensation outcomes for victims depending on whether they are compensated via the government scheme or through standard liability channels.