Future Fortune, Present Debt: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Bankrupt Beneficiary's Life Insurance Claim Rights

Date of Judgment: April 28, 2016

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. 330 (Ju) of 2015 (Main claim for confirmation of non-existence of debt, counterclaim for restitution of unjust enrichment)

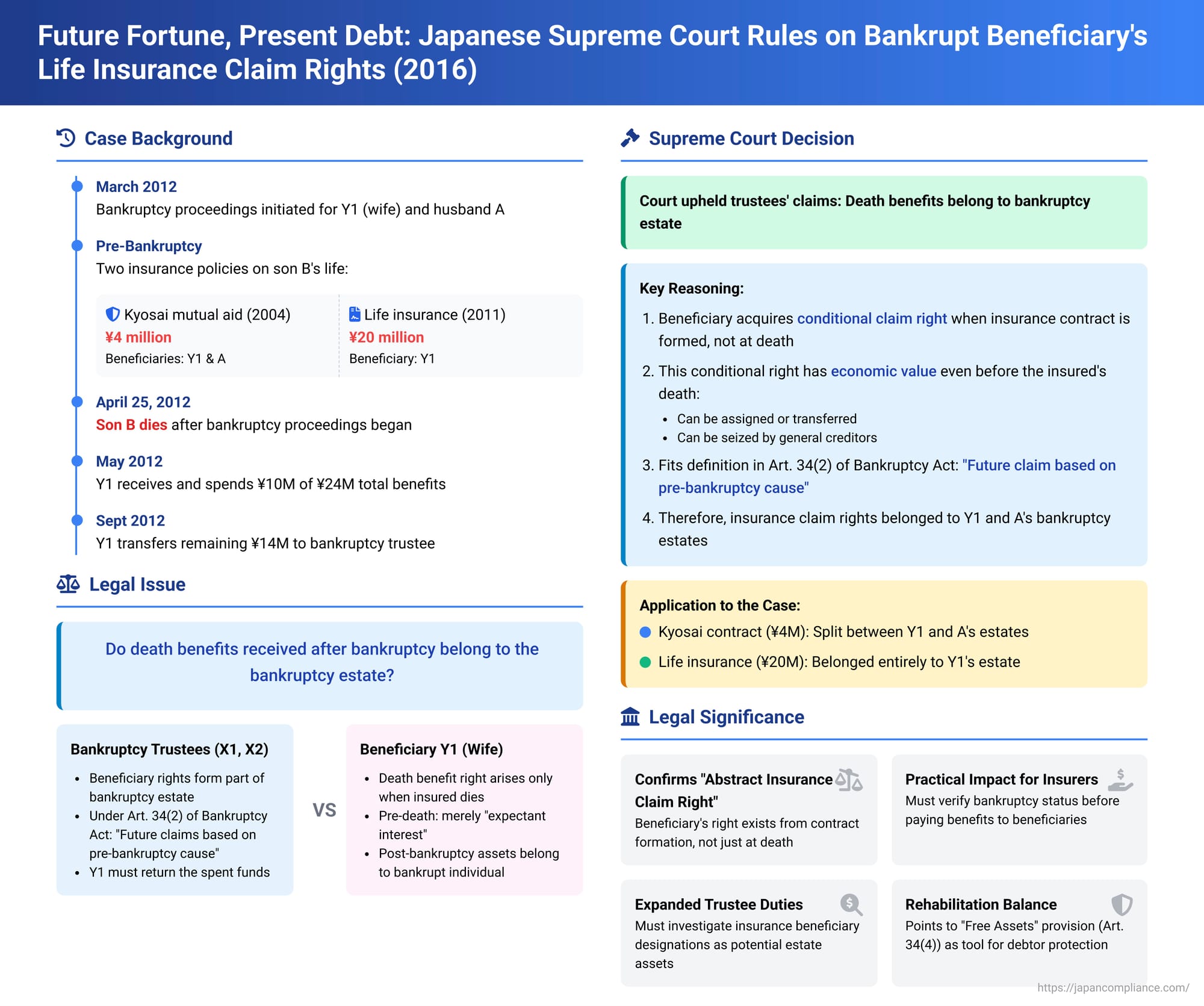

When an individual is designated as a beneficiary on a life insurance policy, they hold an expectation of receiving proceeds upon the insured's death. But what happens if the beneficiary declares bankruptcy while the insured person is still alive? If the insured then passes away after the beneficiary's bankruptcy proceedings have commenced, do those life insurance proceeds belong to the bankrupt beneficiary for their fresh start, or do they become part of the bankruptcy estate to be distributed among their creditors? This critical question, balancing the nature of insurance benefits with the principles of bankruptcy law, was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant decision on April 28, 2016.

A Family Tragedy Compounded by Bankruptcy: Facts of the Case

In March 2012, bankruptcy proceedings were initiated for both Y1 (a wife, the defendant/appellant in the main appeal) and her husband, A. Two individuals, X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs/respondents, represented by the same lawyer), were appointed as the respective bankruptcy trustees for Y1 and A.

Prior to these bankruptcy proceedings, B, the eldest son of Y1 and A, was the insured under two separate contracts:

- A life mutual aid (kyosai) contract established in 2004 with C Mutual Aid Life Cooperative Federation, with a death benefit of 4 million yen. The designated beneficiaries for this contract were both Y1 and A.

- A life insurance contract established in 2011 with D Life Insurance Mutual Company, with a death benefit of 20 million yen. The designated beneficiary for this policy was Y1.

Tragically, on April 25, 2012—after the commencement of Y1 and A's bankruptcy proceedings—their son B passed away.

In May 2012, Y1 proceeded to claim and receive the death benefits from both contracts, totaling 24 million yen. She subsequently spent 10 million yen of these funds (referred to as "the disputed sum"). It was noted that 8 million yen of this disputed sum was spent based on the advice of her lawyer, Y2, who also became a defendant/appellant in the proceedings. In September 2012, Y1 transferred the remaining 14 million yen from the insurance payouts into a trust account managed by the bankruptcy trustee, X1.

The bankruptcy trustees, X1 and X2, then filed a lawsuit. They argued that the rights to claim the death benefits from both the kyosai and life insurance contracts (collectively, "the insurance claim rights") properly belonged to the bankruptcy estates of Y1 and/or A. They sued Y1 for unjust enrichment concerning the 10 million yen she had spent. They also sued Y1's lawyer, Y2, alleging a tortious act (professional negligence) for advising Y1 to spend 8 million yen of those funds. Specifically, X1 (as trustee for Y1) sought joint payment of 8 million yen (plus damages/interest), and X2 (as trustee for A) sought joint payment of 2 million yen (plus damages/interest).

Y1, in turn, filed a counterclaim against the trustee X1. She argued that the insurance claim rights did not belong to her bankruptcy estate, and therefore, the 14 million yen she had transferred to X1's trust account was an unjust enrichment of the estate. She demanded the return of this 14 million yen plus interest.

Both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (on appeal) ruled largely in favor of the bankruptcy trustees. They held that the insurance claim rights constituted "future claims that the bankrupt may assert based on a cause that arose before the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings" under Article 34, paragraph 2, of Japan's Bankruptcy Act. As such, these rights belonged to the respective bankruptcy estates of Y1 and A. The lower courts generally upheld the trustees' claims against Y1 and Y2 (partially for Y2) and dismissed Y1's counterclaim.

Y1 and Y2 appealed to the Supreme Court. Their core argument was that in a life insurance contract for the benefit of a third party, the beneficiary's right to claim the death benefit arises only at the moment the insured person dies. Before that point, they contended, the beneficiary possesses merely an "expectant interest" (kitai-teki rieki)—a hope or possibility of a future benefit—rather than a concrete legal right. Therefore, they argued, the lower courts had erred in law by finding that these pre-death "interests" could form part of the bankruptcy estates.

The Legal Question: Does a Future Insurance Payout Belong to a Bankrupt's Estate?

The central legal issue was the characterization of a beneficiary's interest in a life insurance policy when the beneficiary enters bankruptcy while the insured is still living. Specifically, does this interest qualify as an asset that should be included in the bankruptcy estate?

Japan's Bankruptcy Act, in Article 34, paragraph 1, embraces the "fixation principle" (kotei shugi). This means that the bankruptcy estate generally comprises all property belonging to the bankrupt individual at the precise time the bankruptcy proceedings are officially commenced. Any property acquired by the bankrupt after this point is typically considered "newly acquired property" (shintoku zaisan) and remains the bankrupt's personal asset, free from the claims of the bankruptcy estate.

However, Article 34, paragraph 2, of the Bankruptcy Act clarifies and, in a sense, expands this principle. It states that the bankruptcy estate also includes "future claims that the bankrupt may assert based on a cause that arose before the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings." This provision is understood to cover rights that may not be fully matured or concretized at the start of bankruptcy but have their foundational cause rooted in the pre-bankruptcy period, such as rights under a pending condition.

The dispute, therefore, was whether a life insurance beneficiary's interest, before the insured's death, fell into this category of "future claims."

The Supreme Court's Decision: Yes, It Belongs to the Estate

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, thereby affirming the lower courts' conclusions. The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of the Beneficiary's Right: The Court began by referencing its own precedent from February 2, 1965. It stated that the beneficiary of a death benefit in a third-party life insurance contract acquires a claim right to that death benefit at the moment the insurance contract is concluded. This right is, however, conditional upon the insured dying within the period specified in the contract.

- Existing Economic Value: Even before the insured's death, this conditional claim right is not a mere expectancy devoid of legal or economic substance. The Court pointed out that such a right can be disposed of by the beneficiary (e.g., assigned or sold, though the market for such rights may be limited) and can also be seized by the beneficiary's general creditors through legal execution procedures. Therefore, the right undeniably possesses a certain economic value.

- Application of Bankruptcy Act Article 34, paragraph 2: Given these characteristics, the Supreme Court concluded that a death benefit claim right held by a bankrupt beneficiary—arising from a third-party life insurance contract that was established before the beneficiary's bankruptcy proceedings commenced—fits the definition of a "future claim that the bankrupt may assert based on a cause that arose before the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings," as stipulated in Article 34, paragraph 2, of the Bankruptcy Act. Consequently, this right properly belongs to the beneficiary's bankruptcy estate.

Application to the Specific Facts:

In this case, both the life kyosai contract and the life insurance contract on B's life had been concluded well before the bankruptcy proceedings for Y1 and A began in March 2012.

- For the life kyosai contract, Y1 and A were joint beneficiaries. Therefore, upon B's death, the claim right to the kyosai benefits belonged to the bankruptcy estates of Y1 and A in equal one-half shares.

- For the life insurance contract, Y1 was the sole designated beneficiary. Thus, the claim right to these benefits belonged entirely to Y1's bankruptcy estate.

The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment to be correct in its reasoning and outcome. It also distinguished a 1995 Supreme Court precedent cited by the appellants, deeming it not relevant to the present case.

Unpacking the Rationale: The "Abstract Insurance Claim Right"

The Supreme Court's decision aligns with what has been the prevailing view among legal scholars in Japan. This view posits that a beneficiary's right to insurance proceeds is not something that springs into existence only at the moment of the insured's death. Rather, an "abstract insurance claim right" (chūshōteki hokenkin seikyūken)—a conditional right—is considered to arise when the insurance contract is formed. This right, though contingent on the future event of the insured's death (and potentially other conditions), is a legally recognized interest with present characteristics, including assignability and seizability, and therefore, economic value. Because its "cause" (the insurance contract naming the beneficiary) arose before bankruptcy, it becomes part of the bankruptcy estate even if the condition (the insured's death) is fulfilled only after bankruptcy proceedings have commenced.

Addressing Counterarguments

The opposing minority view, which argues that the claim right should only enter the bankruptcy estate if the insured event occurs before bankruptcy starts, typically raises several points:

- Low Pre-Death Value and Creditor Expectation: It's argued that because the beneficiary's status can be changed by the policyholder, and the probability of the insured event occurring can be low or uncertain, the pre-death conditional right has minimal economic value, and thus creditors would have little expectation of recovering from it. The prevailing view, implicitly endorsed by the Supreme Court, counters that even a low or uncertain economic value does not preclude an asset from being part of a bankruptcy estate or from being subject to seizure.

- Hindering the Beneficiary's Rehabilitation (Fresh Start): Another concern is that including such future potential benefits in the bankruptcy estate could impede the bankrupt beneficiary's ability to achieve financial rehabilitation. The general response to this, within the framework of Japanese bankruptcy law, is that the need for a bankrupt's rehabilitation and livelihood security is primarily addressed through specific provisions such as Article 34, paragraph 4, of the Bankruptcy Act. This article allows the court, upon application, to expand the scope of "free assets" (property that the bankrupt can retain, exempt from the bankruptcy estate) if deemed necessary for maintaining the bankrupt's livelihood. This allows for a case-by-case assessment rather than a blanket exclusion of such insurance rights.

- Prolonging Bankruptcy Proceedings: A practical objection is that if such conditional rights are part of the estate, bankruptcy proceedings might be unduly prolonged, as the trustee would have to wait until the insured event occurs (or doesn't) to finalize the estate. However, bankruptcy trustees are not necessarily required to wait indefinitely. They have options such as attempting to realize the present value of the conditional right (e.g., by selling it, if feasible, though this can be difficult for life insurance beneficiary rights), or, after proper assessment, seeking court permission to abandon the asset if its administration is not economically beneficial to the creditors.

Practical Implications for Insurers and Bankruptcy Trustees

The Supreme Court's 2016 decision has important practical consequences:

- For Insurers: When paying out death benefits, insurers need to exercise caution if they are aware that a designated beneficiary is or has recently been in bankruptcy proceedings. Paying the proceeds directly to the bankrupt beneficiary without consulting the bankruptcy trustee could expose the insurer to the risk of having to pay a second time to the trustee if the claim right is deemed part of the bankruptcy estate.

- For Bankruptcy Trustees: Trustees have a duty to investigate whether individuals undergoing bankruptcy hold beneficiary designations on existing life insurance or kyosai policies. If such conditional rights exist, the trustee must then manage them as part of the bankruptcy estate. This involves complex decisions regarding their valuation, the feasibility of liquidation (which can be challenging for such assets), or potentially seeking court approval for their abandonment or for their inclusion in the bankrupt's free assets under Article 34(4). In many cases, particularly where the likelihood of the insured event occurring during the bankruptcy proceeding is low, or the administrative costs are high relative to the uncertain future value, a flexible approach involving negotiation with the policyholder (e.g., to change the beneficiary in exchange for a contribution to the estate) or applying for expansion of free assets might be pursued.

The commentary notes that if the administrative costs associated with including these abstract claim rights in bankruptcy estates prove to be generally too high or problematic, it might warrant legislative consideration for their exclusion.

Regarding the scope of this judgment, its logic suggests a general applicability to various types of insurance claim rights arising from pre-bankruptcy contracts. Specific concerns about fairness in individual cases would likely be addressed through the mechanism of expanding free assets. One specific area of discussion noted in the commentary involves non-life (indemnity) insurance: if a bankrupt insured suffers a loss covered by indemnity insurance due to a third party's tort after bankruptcy commencement, and the trustee receives the insurance payout, it could inadvertently allow the insurer to be subrogated to the bankrupt's tort claim against the third party. This tort claim would normally be "newly acquired property" belonging to the bankrupt personally. Here too, it is suggested that the expansion of free assets could be a tool to ensure a fair outcome.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2016 decision brings important clarity to the treatment of a bankrupt beneficiary's rights under a life insurance policy in Japan. It firmly aligns with the prevailing legal theory that a beneficiary's interest, even before the insured's death, constitutes a conditional legal right with economic value, not merely a speculative hope. As such, if this right is rooted in a contract established before bankruptcy, it forms part of the bankruptcy estate available to creditors. While this ruling underscores the "fixation principle" of bankruptcy law, it also implicitly points to the importance of other mechanisms within the Bankruptcy Act, such as the expansion of free assets, to ensure that the fundamental goals of debtor rehabilitation and livelihood protection are adequately considered in the administration of individual bankruptcy cases involving such future, and often uncertain, insurance benefits.