Future Dangers, Present Liability: Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies "Basic Safety" in Building Defects

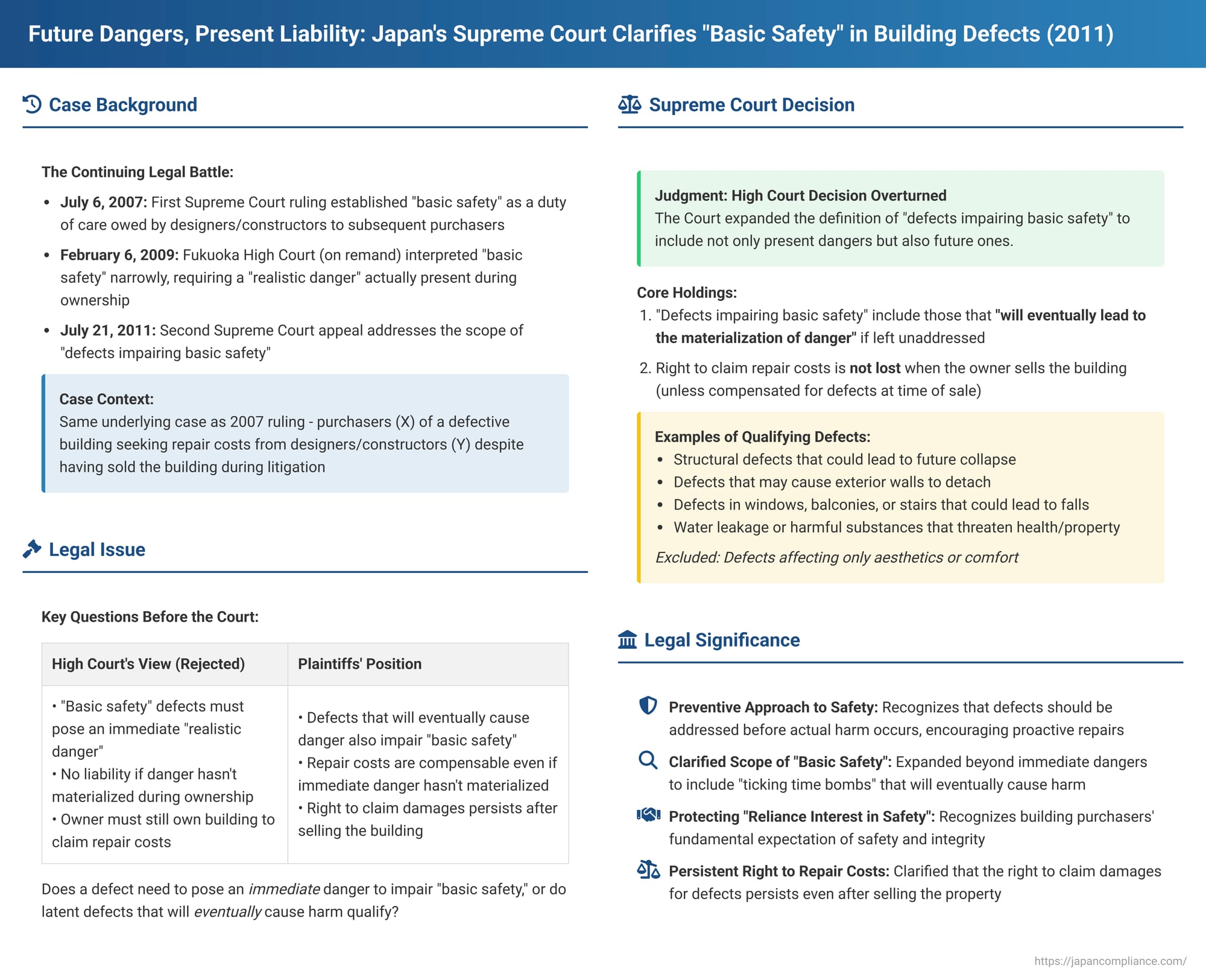

In a continuation of a significant legal battle over construction defects, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a further clarifying judgment on July 21, 2011 (Heisei 21 (Ju) No. 1019). This decision, the second Supreme Court appeal in the same underlying case (previously discussed as Case 92, the judgment of July 6, 2007), refined the crucial concept of "defects impairing basic safety" for which building designers, constructors, and supervisors can be held liable in tort, even to subsequent purchasers of a building.

Recap: The First Supreme Court Appeal (The Foundation)

The first Supreme Court appeal (Heisei 19.7.6, hereafter "the first appeal judgment") established a landmark principle: professionals involved in a building's design and construction (designers/constructors) owe a duty of care to ensure the building's "basic safety". This duty extends not only to their direct contractual clients but also to other "residents, etc." (a broad category including subsequent purchasers, users, neighbors, and passersby). If this duty is breached, resulting in a building with defects that compromise this basic safety and thereby cause harm to the life, body, or property of these individuals, the designers/constructors are liable in tort for the resulting damages. This liability applies unless "special circumstances" exist, such as the claimant knowingly purchasing the building with awareness of the specific defects. The first appeal judgment remanded the case to the High Court to determine whether such defects existed in the plaintiffs' building and if they had suffered damages as a result.

The High Court's Interpretation on Remand: "Realistic Danger" Required

Following the first appeal judgment, the Fukuoka High Court, in its second review of the case (Heisei 21.2.6, hereafter "the second High Court judgment"), adopted a narrow interpretation of "defects impairing basic safety". It held that such defects must pose a "realistic danger" (genjitsuteki na kikensei) to the life, body, or property of residents, etc.. The High Court stated that this didn't simply mean a violation of building codes and that "trivial defects" should not give rise to tort liability.

Furthermore, because the plaintiffs' claim was for repair costs (a form of property damage), the High Court reasoned that this damage must have occurred while the plaintiffs actually owned the building. (The building in question had been sold at auction while the initial trial was ongoing.) Based on this, the High Court concluded that for tort liability to attach, the "defect impairing basic safety" must have posed a realistic danger before the building was sold at auction. Finding that no such "realistic danger" had actually materialized to the lives, bodies, or properties of residents, etc., during the plaintiffs' ownership period, the High Court once again dismissed their tort claim against the designers/constructors. The plaintiff (X, one of the original purchasers who had also succeeded the rights of the other original co-purchaser A) appealed this decision.

The Second Supreme Court Appeal (July 21, 2011): Broadening the Scope of "Danger"

The Supreme Court, in this second appeal judgment, overturned the second High Court judgment and remanded the case yet again for further proceedings. The core of this decision was a significant clarification and broadening of what constitutes a "defect impairing basic safety":

- Beyond "Realistic Present Danger": The Court explicitly stated that the High Court's interpretation was too narrow. A "defect impairing basic safety as a building," as referred to in the first appeal judgment, is not limited to defects that are already causing or posing a "realistic danger" to life, body, or property at the present moment.

- The "Future Materialization of Danger" Standard: Crucially, the Supreme Court held that such a defect also includes situations where, "in light of the nature of the said defect, if it is left unaddressed, it will eventually lead to the materialization of danger to the lives, bodies, or properties of residents, etc.". This means that a latent defect, which may not be an immediate threat but is a ticking time bomb, can still qualify as one that impairs basic safety.

Illustrative Examples Provided by the Court:

To provide concrete guidance, the Supreme Court offered examples of defects that would meet this broadened standard:

* Structural Defects: Defects related to the building's structural strength which, if neglected, could lead to the corrosion of rebar, deterioration of materials, reduction in concrete's load-bearing capacity, and ultimately result in the collapse (in whole or in part) of the building.

* Non-Structural Defects with Serious Safety Implications: Even defects not directly related to structural strength can qualify if, when left unaddressed, they pose significant risks. Examples include:

* Exterior walls detaching and falling onto passersby below.

* Defects in openings (windows, doors), balconies, or stairs that could cause building users to fall, leading to personal injury.

* Water leakage, or the generation or emission of harmful substances, that could endanger the health or damage the property of the building's users.

* Exclusion of Minor Defects: The Court also clarified what does not meet the standard: "Defects that merely impair the aesthetic appearance of the building or the comfort of the residents' living environment" are excluded.

Damages and Subsequent Sale of Property

The Supreme Court also addressed the issue of a claimant's right to damages, particularly when the property changes hands:

- Right to Claim Repair Costs: A building owner who acquires a building that has defects impairing its basic safety can claim damages equivalent to the cost of repairing those defects from the responsible designers/constructors (provided no "special circumstances," as noted in the first appeal judgment, such as knowingly purchasing the defective building on that basis, exist).

- Retention of Claim After Sale: Significantly, the Court ruled: "Even if the said owner subsequently loses ownership of the building, for example by selling it to a third party, they do not automatically lose the right to claim damages that they had once acquired, unless special circumstances exist, such as having received compensation equivalent to the repair costs at the time of the sale". This means that the claim for damages, once vested in the owner who discovered or was affected by the defect, is not necessarily extinguished simply because they no longer own the property. The commentary suggests a new owner might also acquire a claim.

Why This Broader Definition of "Danger" Matters

This clarification by the Supreme Court has important practical and legal consequences:

- Encouraging Preventive Action: By recognizing defects that pose a future danger, the Court encourages proactive repair and discourages a wait-and-see approach until actual harm occurs. This is vital for ensuring long-term building safety.

- Reflecting an Owner's Potential Liability: Owners of buildings with such defects could themselves face significant liability (e.g., under Article 717 of the Civil Code for defective structures on land) if they fail to make necessary repairs and the defect subsequently causes injury or damage. The Supreme Court's stance allows such owners to seek recompense for these necessary repair costs from the original designers/constructors who created the underlying risk. The commentary notes that the likelihood of severe harm in multi-unit dwellings (compared to single-family homes) if such defects are neglected, necessitating prompt repair, was likely a consideration.

- Protecting the "Reliance Interest in Safety": The broader definition acknowledges that an owner invests in a property with a fundamental expectation of safety and integrity. When this basic safety is compromised by latent defects that will eventually lead to danger, their investment and reliance are harmed. The repair costs can be seen as the monetary measure required to restore this fundamental safety and honor that reliance. The commentary points to "reliance interest in safety" (anzensei shinrai rieki) as a potential legal interest infringed, which helps justify repair costs as damages.

"Special Circumstances" and Lingering Questions

The concept of "special circumstances" that might negate the designers/constructors' liability (such as the buyer knowingly purchasing the building "as is" with full awareness of specific safety-impairing defects) remains an area for careful application. The commentary from the previous case (Case 92) questioned the precise legal basis for this exception, for instance, whether it's based on the victim's consent or a waiver of the claim, especially since the buyer's direct relationship is with the seller, not the original builders. This second appeal judgment reiterates this exception without extensive elaboration, suggesting its application will depend heavily on the specific facts of future cases.

Following this second Supreme Court remand, the Fukuoka High Court, in a subsequent ruling (January 10, 2012), conducted a detailed examination of the building's various parts based on the clarified standard and ultimately recognized the plaintiffs' claim for repair costs for some of the cracks and other defects.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision in the second appeal of this building defect case significantly reinforced and clarified its groundbreaking 2007 ruling. By defining "defects impairing basic safety" to encompass not only those posing an immediate, realistic danger but also those that will eventually materialize into danger if left unaddressed, the Court has substantially strengthened the protection afforded to building owners, users, and the public against latent safety hazards. This judgment underscores that the responsibility of building professionals is not merely to avoid imminent catastrophe but to deliver structures that are fundamentally and enduringly safe, recognizing the long-term implications of their work. It also provides important guidance on a property owner's ability to claim damages for such defects even after they may have sold the property.