Supreme Court on Tort Damages vs. Ongoing Pensions: Japan’s 1977 “Non‑Deduction” Rule Explained

TL;DR

On 25 Oct 1977, Japan’s Supreme Court held that future social‑insurance pensions must not be deducted when calculating lump‑sum tort damages; only benefits actually paid by judgment day are offset. The ruling enlarged plaintiffs’ awards and triggered later legislative tweaks.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Workplace Accident, Total Disability, and Pension Entitlements

- Lower Court Ruling: Deduction of Estimated Future Benefits

- Legal Framework: Coordinating Tort Damages and Social Insurance

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (October 25 1977): Actual Payment as the Key

- Implications and Significance: The Non‑Deduction of Future Benefits Rule

- Conclusion

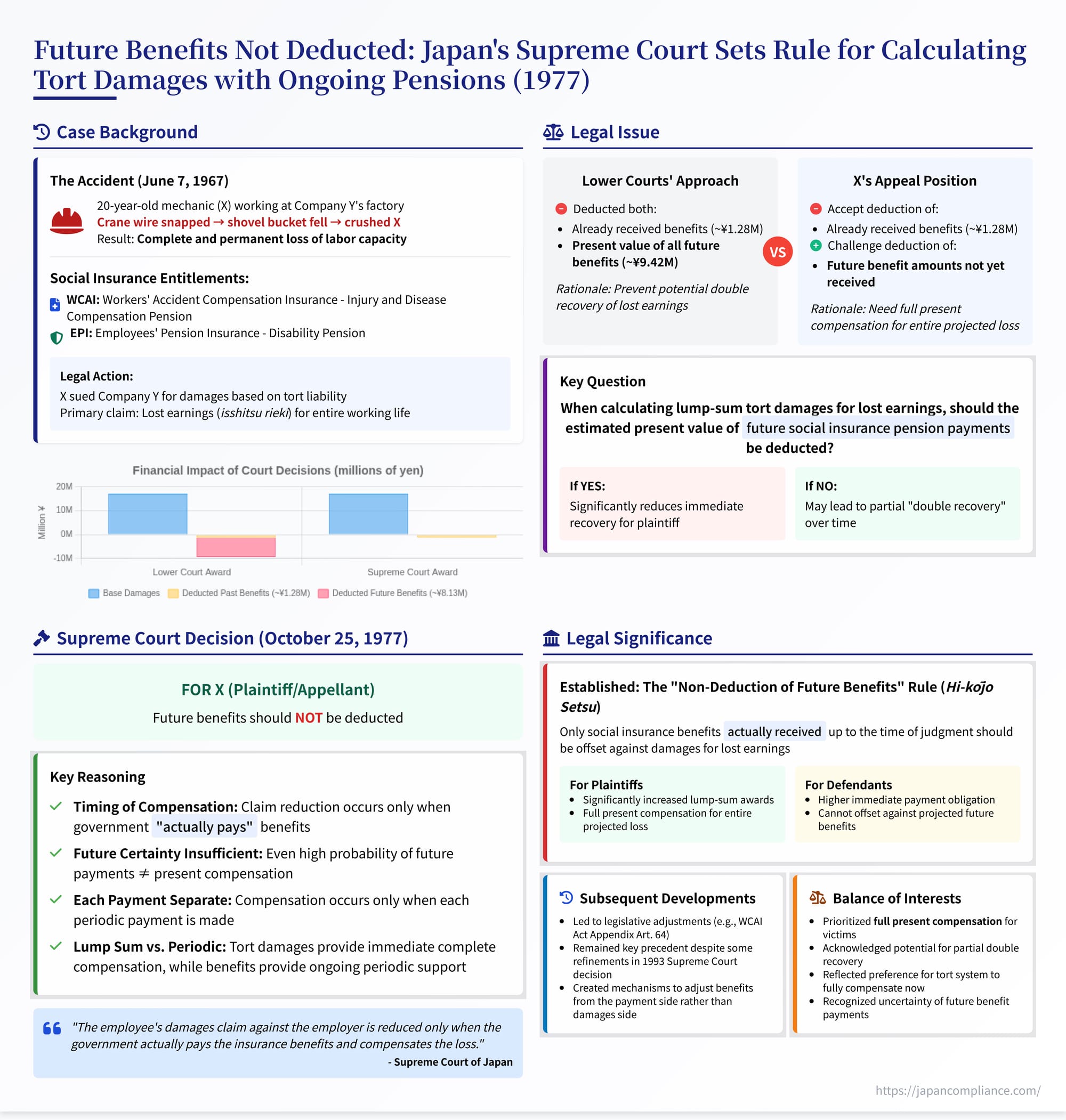

On October 25, 1977, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pair of influential judgments that significantly shaped how tort damages are calculated when the injured party is also receiving ongoing social insurance benefits, particularly pensions. One of these key cases (Case No. 1975 (O) No. 621, "Damages Claim Case") addressed whether the estimated future payments of Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance (WCAI) benefits and Employees' Pension Insurance (EPI) disability pensions should be deducted from a lump-sum damages award for lost earnings sought from the employer responsible for the injury. The Court ruled decisively against deducting future benefits, establishing the principle that only social insurance benefits actually received by the time of judgment should be offset against damages for lost earnings. This "non-deduction of future benefits" rule (hi-kōjo setsu) profoundly impacted personal injury litigation involving long-term social security recipients in Japan.

Factual Background: Workplace Accident, Total Disability, and Pension Entitlements

The case involved a severe workplace accident with long-term consequences:

- The Accident: On June 7, 1967, X (the appellant), then 20 years old, was working as a mechanic for Company Y (the appellee) at their factory. While inspecting and repairing a shovel car, the wire rope of a crane lifting the shovel's bucket snapped. The bucket fell, crushing X underneath.

- Injuries and Consequences: X suffered catastrophic injuries, including brain contusion and cervical spine fractures, resulting in complete and permanent loss of labor capacity.

- Tort Claim: X sued his employer, Company Y, for damages based on tort liability. The lower courts found Company Y liable, likely under Civil Code Article 717 (liability for defects in structures – the faulty crane) or general negligence principles (Article 709/715). The primary component of X's damages claim was compensation for lost earnings (逸失利益 - isshitsu rieki) – the income he would have earned over his working life had the accident not occurred.

- Social Insurance Benefits: Due to the work-related nature and severity of his injuries, X became entitled to long-term periodic benefits from two social insurance systems:

- Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act): Initially Temporary Absence Compensation Benefit, later transitioning to a long-term Injury and Disease Compensation Pension (傷病補償年金 - shōbyō hoshō nenkin).

- Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPI Act, pre-1985 version): A Disability Pension (障害年金 - shōgai nenkin) based on his disability level.

Lower Court Ruling: Deduction of Estimated Future Benefits

The lower courts (both first instance and the High Court) calculated X's lost earnings based on his potential earnings trajectory until retirement age (presumably age 63 in the first instance calculation). However, when determining the final amount Company Y should pay, they applied the principle of son'eki sōsai (offsetting gains and losses) by deducting the social insurance benefits X was receiving. Critically, they deducted not only the benefit amounts X had already received up to the time of judgment, but also the estimated present value of the future stream of WCAI and EPI pension payments X was expected to receive over his remaining lifespan (or until eligibility ceased). The High Court calculated this total present value of future benefits to be 9,415,299 yen and subtracted it from the calculated lost earnings, significantly reducing the lump-sum damages awarded to X.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, challenging the legality of deducting the estimated value of future, not-yet-received pension benefits from his present damages award.

Legal Framework: Coordinating Tort Damages and Social Insurance

The core issue involved the coordination between the employer's tort liability to compensate for damages caused by its fault and the separate system of social insurance benefits provided by the government. Key legal principles included:

- Employer's Tort Liability: Based on the Civil Code, requiring compensation for damages caused by negligence or other specified grounds.

- LSA Disaster Compensation & WCAI: The Labour Standards Act (LSA) imposes no-fault disaster compensation duties on employers (Arts. 75 ff.). The WCAI Act provides insurance benefits that largely substitute for these LSA duties (LSA Art. 84(1)).

- EPI Disability Pension: Provides income support related to long-term disability, funded by contributions from employers and employees, plus government subsidies.

- Coordination Principle: Legal provisions (like LSA Art. 84(2), applicable by analogy) and general principles of equity aim to prevent double recovery by adjusting the employer's tort liability when WCAI or EPI benefits compensate for the "same cause/event" (同一の事由 - dōitsu no jiyū) as the damages claimed.

The dispute centered on how this adjustment should account for future periodic benefit payments when calculating a present lump-sum damages award.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (October 25, 1977): Actual Payment as the Key

The Supreme Court agreed with X and overturned the High Court's decision regarding the deduction of future benefits. It held that only benefits actually received should be deducted.

1. Nature of Social Insurance Benefits and Employer Liability:

The Court began by reaffirming its understanding of the relationship between social insurance and employer liability:

- Substitutive and Compensatory: WCAI benefits are substantively the government fulfilling the employer's LSA disaster compensation duties. Both WCAI and EPI benefits (like the disability pension) also have the nature of compensating for the recipient's loss (songai no tenpo no seishitsu o mo yūsuru).

- Employer Exemption Triggered by Payment: When an accident is caused by the employer's act (as here), and the government pays WCAI or EPI benefits, the employer (Company Y) is exempted from their corresponding civil law damages liability (tort/contract) "for the same cause/event" (dōitsu no jiyū) up to the value of the benefits paid. This is based on applying LSA Art. 84(2) by analogy for WCAI benefits and based on "principles of equity" (kōhei no rinen) for EPI benefits.

2. The Timing of Loss Compensation and Claim Reduction:

The crucial step in the Court's reasoning concerned when the employee's loss is considered compensated by the insurance benefits, thereby reducing their damages claim against the employer:

- Focus on Actual Compensation: The Court stated that the employee's damages claim against the employer is reduced only when the government "actually pays the insurance benefits and compensates the loss" (genjitsu ni hokenkin o kyūfu shite songai o hoten shita toki ni kagirare). The reduction in the claim happens concurrently with the actual financial compensation provided by the benefit payment.

- Future Certainty Insufficient: The mere certainty or high probability that benefits will be paid continuously in the future is not equivalent to the loss having been compensated at the present time. The actual compensation occurs only when each periodic payment is made.

- No Deduction of Future Benefit Value: Therefore, when an employee claims a lump-sum damages award from the employer (representing present compensation for past and future losses), they are "not required to deduct such future benefit amounts" (konoyōna shōrai no kyūfu gaku o... kōjo suru koto o yōshinai) from the damages claimed. The offset is limited to benefits already paid.

3. Reference to Parallel Judgment:

The Court explicitly cited its own judgment delivered on the same day (May 27, 1977, the "Nitahara Nakamura case," 1975 (O) No. 431) as establishing this same principle. (This suggests the reasoning in both cases was likely very similar, focusing on the need for actual payment before offset occurs).

4. Application and Recalculation:

Applying this rule, the High Court's deduction of the ~9.4M yen present value of future WCAI and EPI pensions was an error of law. Only the ~1.28M yen in benefits X had actually received by the close of the High Court's proceedings should have been deducted from the lost earnings calculation. The Supreme Court proceeded to recalculate the damages accordingly, adding back the improperly deducted future benefit value (~8.13M yen) to the amount awarded by the High Court (adjusting the final figures slightly based on its own calculations, resulting in a total award against Company Y of 17,135,085 yen plus interest).

Implications and Significance: The "Non-Deduction of Future Benefits" Rule

This 1977 Supreme Court ruling (along with its companion case) had a profound and lasting impact on tort damages litigation in Japan involving victims receiving social security pensions:

- Established Non-Deduction Rule (Hi-kōjo Setsu): It established the dominant legal principle at the time that the present value of future social insurance pension payments should not be deducted when calculating lump-sum tort damages for lost earnings. Only benefits received up to the point of judgment are offset.

- Increased Lump-Sum Awards: This significantly increased the potential lump-sum recovery for plaintiffs in severe injury or death cases, as their future social security income was no longer subtracted from their estimated lost earnings claim against the tortfeasor.

- Focus on Present Compensation: The rationale prioritized providing the victim with full present compensation for their entire projected loss via the tort damages award, without discounting it based on uncertain future periodic payments from a separate source (social insurance).

- Acknowledged Potential for Double Recovery: The Court implicitly acknowledged that this rule could lead to a degree of "double recovery" – the plaintiff receives a lump sum compensating for future lost earnings, and also receives future pension payments intended to replace some of those same earnings. However, it deemed the principle of providing full present tort compensation and the uncertainty of future benefits to outweigh this concern at the damages calculation stage.

- Led to Subsequent Legislative Adjustments: The potential for double recovery created by this judicial rule eventually spurred legislative action. Notably, amendments to the WCAI Act (e.g., Appendix Art. 64, introduced later) created mechanisms to adjust the social insurance benefits themselves if the recipient subsequently receives tort damages covering the same loss. These provisions allow the government to suspend future WCAI pension payments up to a certain limit once tort damages are paid, thus addressing the double recovery issue from the benefit payment side rather than the damages calculation side.

- Distinction from Heisei 5 (1993) Ruling: It's important to distinguish this ruling from the 1993 Grand Bench decision (analyzed in a previous request). The 1993 decision upheld the principle of not deducting future benefits established here, but slightly modified the calculation of past benefits subject to offset, extending it to include benefits whose payment was definitively due by the close of trial, even if not yet disbursed. The core principle against deducting uncertain future payments remained intact.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's October 25, 1977, decision in this case established a key principle for calculating tort damages in Japan when the victim also receives social insurance pensions: the estimated present value of future pension payments should not be deducted from the damages awarded for lost earnings. The Court held that the offset (or adjustment under relevant statutes) should be limited to the amount of benefits actually received by the plaintiff up to the time of judgment. This "non-deduction of future benefits" rule prioritized providing full present compensation for the tortious loss, even if it created a potential overlap with future periodic benefit payments, significantly impacting damage calculations in personal injury and wrongful death litigation, and prompting later legislative responses to address the coordination from the benefit payment side.

- What Types of Damages Can Be Claimed and How Are They Calculated in Japanese Torts?

- Tortious Acquisition of a Judgment and Res Judicata: Seeking Damages After a Deceptively Obtained Ruling

- Retained Title and Trespassing Cars: Who Is Responsible for Removal in Japan?

- Workers’ Compensation – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Overview of Japan’s Public Pension System – MHLW