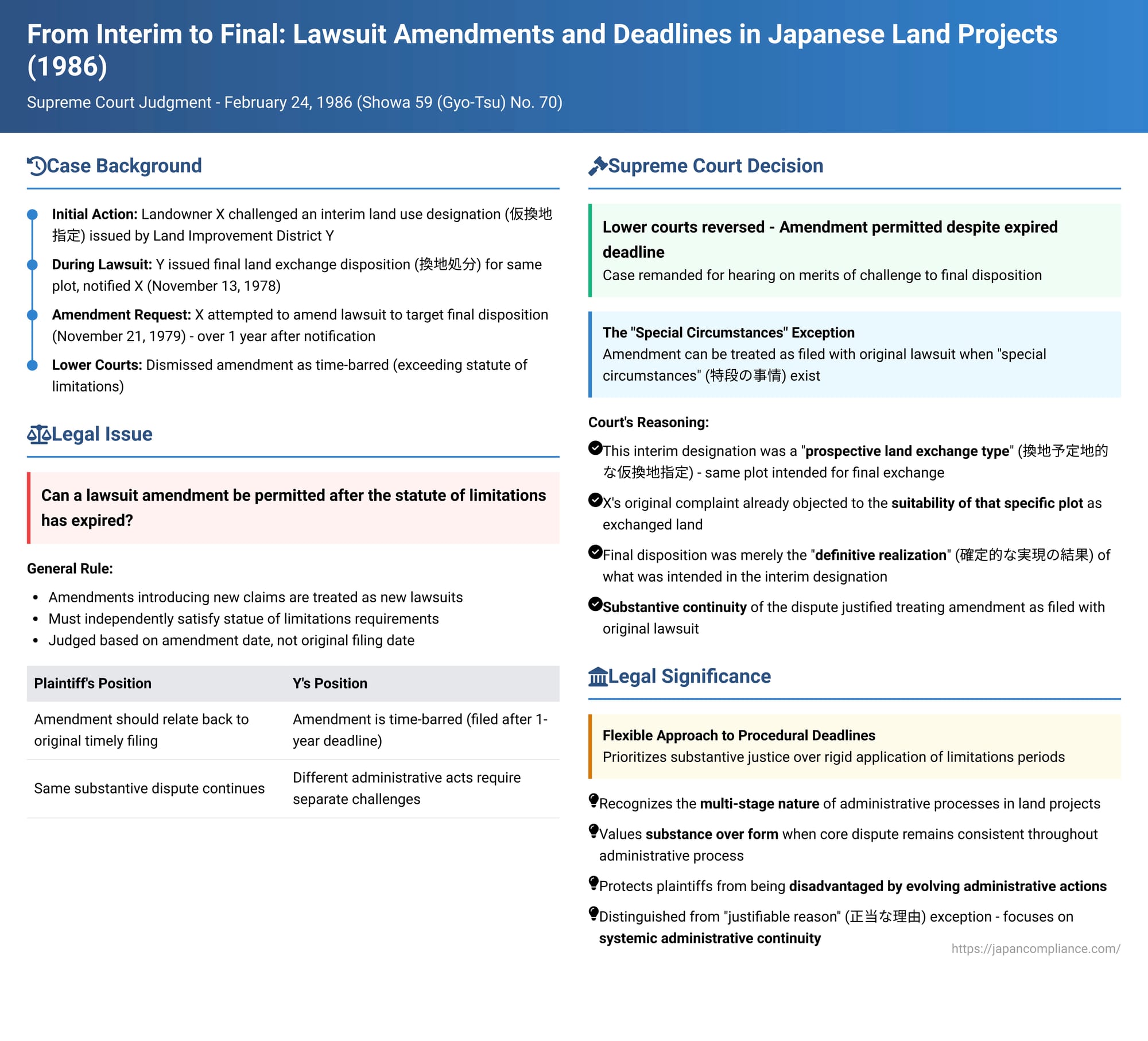

From Interim to Final: Lawsuit Amendments and Deadlines in Japanese Land Projects

Judgment Date: February 24, 1986

Case Number: Showa 59 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 70 – Claim for Revocation of Temporary Use Land Designation Disposition

Land improvement projects in Japan often involve a series of administrative actions that can unfold over a considerable period. This can create procedural challenges for landowners who wish to contest these actions, particularly concerning lawsuit deadlines. A 1986 Supreme Court decision addressed a critical issue: if a landowner timely sues to challenge an initial, temporary land designation, can they later amend that lawsuit to challenge a subsequent, final land exchange—even if the deadline for directly challenging the final action has passed? The Court found that, under "special circumstances," such an amendment can be considered timely.

The Land Improvement Saga: A Temporary Designation Becomes Permanent

The case involved X, a landowner, and Y, the Yatsushiro Plain Northern Land Improvement District, which was implementing a land improvement project.

- Y first issued an "interim land use designation" (ichiji riyōchi shitei shobun) to X under Article 53-5(1) of the Land Improvement Act. This designated a temporary plot for X to use while the project was underway.

- X, believing this interim plot did not fairly correspond to their original land (a violation of the "principle of correspondence" - shōō no gensoku), filed an administrative objection. After Y rejected the objection, X timely filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of this interim land use designation.

- While this initial lawsuit was pending, Y proceeded with the project. On March 31, 1978, Y finalized a land exchange plan and, under Article 54(1) of the Act, issued a formal "land exchange disposition" (kanchi shobun) to X. Crucially, this final disposition designated the very same plot of land that had been assigned as the interim use land to be X's permanent exchanged land. X was notified of this final disposition on November 13, 1978.

- On November 21, 1979, more than a year after the final land exchange disposition was made (and thus after the typical statute of limitations for challenging it had expired), X sought to amend the ongoing lawsuit. Instead of challenging the (now superseded) interim designation, X wanted to change the claim to seek revocation of the final land exchange disposition.

The Legal Sticking Point: Amendment After Deadline

The general rule in litigation is that an amendment of a claim, especially one that introduces a new cause of action, is treated like filing a new lawsuit. For statute of limitations purposes, compliance is usually judged based on the date the amendment is made.

Following this general principle, both the Kumamoto District Court and the Fukuoka High Court (the appellate court) dismissed X's amended claim. They reasoned that since the amendment to challenge the final land exchange disposition was made after the statutory period for such a challenge had passed, the claim was time-barred. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: Recognizing "Special Circumstances" (February 24, 1986)

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts' decisions and remanded the case for a hearing on the merits of the challenge to the final land exchange disposition.

The Court acknowledged the general rule: an amended claim must meet its own statute of limitations as of the date of amendment, unless:

- There's a specific legal provision stating otherwise (like Article 20 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act, which deals with specific joinder scenarios and was not directly applicable here for deeming the filing date).

- The "subject matter of the claim" (soshōbutsu) is identical before and after the amendment.

- There are "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō) that would justify treating the new claim, for limitations purposes, as if it had been filed at the time of the original, timely lawsuit. This "special circumstances" exception had been recognized in earlier Supreme Court precedents.

In X's case, the amendment occurred more than a year after the final land exchange disposition, and the Court found that the subject matter of a suit against an interim land use designation is not identical to that of a suit against a final land exchange disposition. Thus, the timeliness of X's amended claim hinged on whether such "special circumstances" existed.

Finding "Special Circumstances"

The Supreme Court found that such "special circumstances" were indeed present:

- The Nature of This Specific Interim Designation: The Court distinguished between two broad types of interim land use designations:

- Those made purely for the temporary necessities of construction, with no intention that the interim land will become the final exchanged land.

- Those that designate the interim land as the prospective or intended site for the final exchanged land.

The Court determined that the interim designation given to X, although occurring before the formal land exchange plan was finalized, was of the second type. It wasn't merely a temporary measure for ongoing works; it was a "prospective land exchange type interim land use designation" (kanchi yoteichi-teki na ichiji riyōchi no shitei shobun). This means Y intended, or at least created a strong expectation, that this interim land would eventually become X's final plot. The interim designation, therefore, effectively established a use-and-profit relationship on that land similar to what a final land exchange would create.

- The Substance of X's Original Complaint: When X initially sued to revoke the interim land use designation, the basis of the complaint was that the designated land did not "correspond" fairly to X's original land. The Supreme Court reasoned that this complaint was not just an objection to the temporary nature or conditions of the interim use. Given that this interim land was effectively a preview of the final exchange, X's lawsuit was, in substance, already an expression of dissatisfaction with that specific parcel of land becoming the final exchanged land. The core grievance about the land's suitability was present from the start.

- Continuity of the Dispute: The Court viewed the initial lawsuit and the amended lawsuit as being deeply interconnected. The subsequent final land exchange disposition, which confirmed the interim land as the final plot, was essentially the "definitive realization" (kakutei-teki na jitsugen no kekka) of the intent already manifested in the interim designation.

The "Treated as Filed" Doctrine Applied

Because of these "special circumstances"—the prospective nature of the interim designation and the substantive continuity of X's grievance—the Supreme Court concluded that the amended claim (seeking revocation of the final land exchange disposition) should, for statute of limitations purposes, be treated as if it had been filed at the same time as the original, timely lawsuit (which challenged the interim land use designation). Therefore, the amended claim was not out of time.

Implications of the Ruling

This 1986 Supreme Court decision provides important flexibility in the application of statutes of limitations, particularly in the context of multi-stage administrative processes like those in land improvement projects.

- It affirmed and applied the "special circumstances" exception, allowing courts to look beyond procedural technicalities to the substance of a dispute when an initial, timely challenge is closely and substantively linked to a subsequent administrative act.

- The ruling emphasizes a substance-over-form approach to prevent plaintiffs from being unfairly disadvantaged by the evolving nature of administrative actions, especially when an early administrative act strongly foreshadows a later, definitive one.

- Legal commentary suggests this case aligns with a broader judicial trend of relaxing the strict application of the general rule regarding amendments and limitations, especially where the core dispute remains consistent. This judgment can be categorized as one where, although strict legal requirements for doctrines like "succession of illegality" might not be met, the substantive equivalence of the underlying claim justifies deeming the amended suit timely.

- It's important to distinguish this "special circumstances" doctrine from the "justifiable reason" (seitō na riyū) exception found in Article 14 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act for late filings. The "justifiable reason" typically pertains to individual, concrete circumstances of the plaintiff (e.g., illness, disaster) that prevented timely filing. In contrast, the "special circumstances" found in this case relate more to the systemic nature of the administrative process, the relationship between the administrative acts, and the continuity of the plaintiff's grievance.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court’s decision in this case offers a degree of procedural fairness, ensuring that a landowner's timely challenge to an early stage of a land improvement project is not automatically nullified if the core grievance continues against a subsequent, closely related administrative act that finalizes the earlier arrangement. By recognizing "special circumstances," the Court prioritized the substantive justice of allowing the claim to be heard over a rigid application of the statute of limitations, thereby acknowledging the realities of protracted administrative processes and the need for adaptable legal remedies.