Freedom to Resign vs. Employer Investment: Training Cost Clawbacks and Restrictions on Leaving Employment in Japan

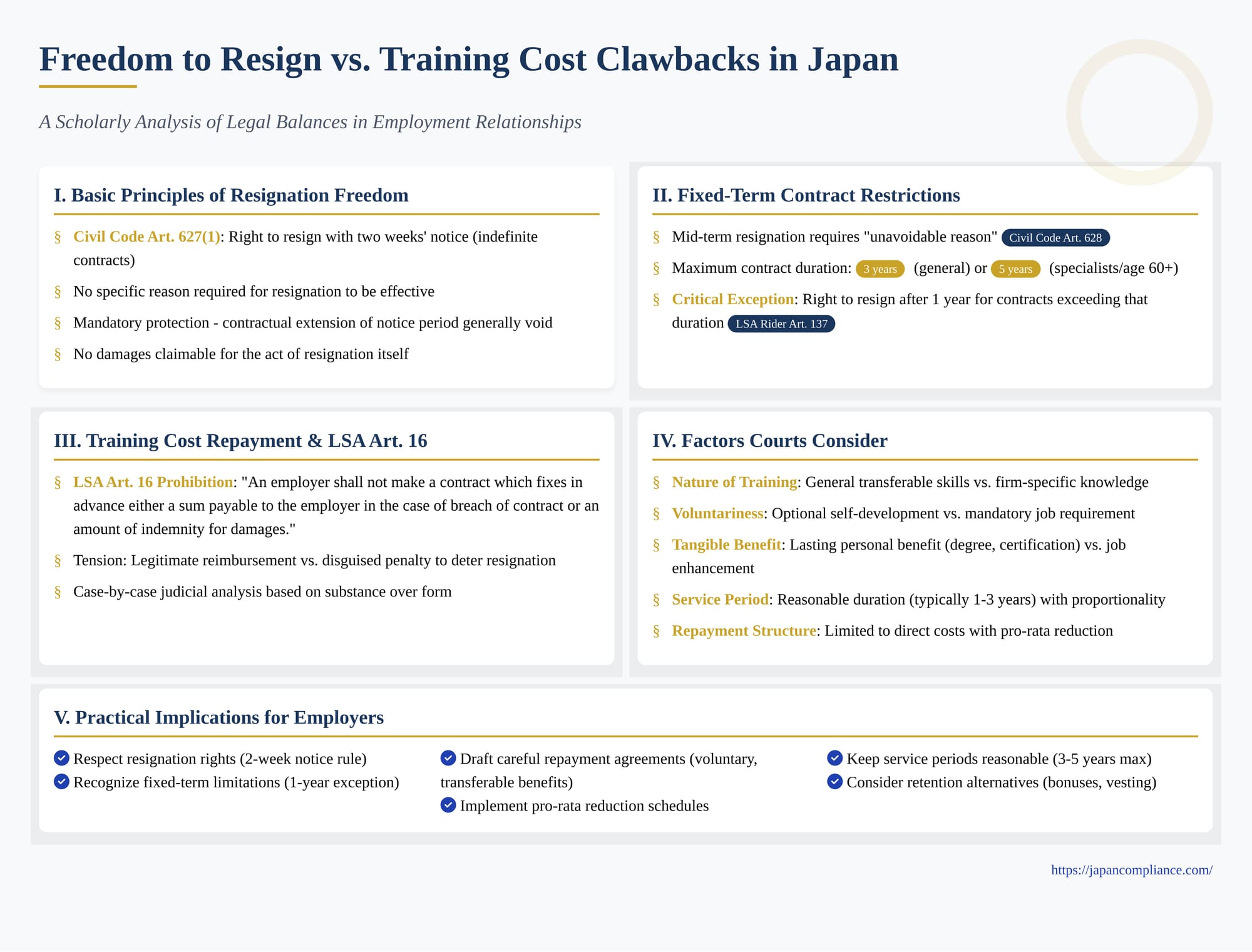

TL;DR: Japan gives indefinite-term employees near-absolute freedom to resign on two weeks’ notice, while fixed-term staff face stricter rules—yet may quit after one year. Training-cost clawback clauses survive only if narrowly drafted under Labor Standards Act Article 16.

Table of Contents

- The Basic Principle: Freedom to Resign from Indefinite Contracts

- Restrictions Under Fixed-Term Contracts

- Training Cost Repayment Agreements (“Clawbacks”) and LSA Art. 16

- Skill Formation Policy Context

- Practical Implications for Employers in Japan

- Conclusion: Prioritizing Freedom of Movement

The ability of an employee to resign from their job is a cornerstone of individual liberty and career mobility in most market economies. However, this freedom often intersects with an employer's desire for workforce stability and the need to recoup investments made in employee development, particularly substantial training costs. Japanese employment law navigates this intersection through a framework that strongly protects the employee's right to leave, while acknowledging certain contractual limitations, especially regarding fixed-term employment and specific agreements on training cost reimbursement.

For international companies employing staff in Japan, understanding the legal boundaries surrounding resignation rights and the enforceability of restrictive agreements is crucial for both talent management and risk mitigation.

The Basic Principle: Freedom to Resign from Indefinite Contracts

For employees on indefinite-term contracts (muki koyō), which represent the traditional "regular" employment (seishain) model in Japan, the fundamental principle is the freedom to resign (taishoku no jiyū).

- Civil Code Art. 627(1): This provision establishes the default rule: an employee can terminate an indefinite employment contract at any time by giving two weeks' notice. No specific reason or "just cause" is required for the resignation to be effective.

- Mandatory Rule for Employees: This right is generally considered a mandatory protection for employees. Contractual clauses or work rules attempting to impose longer notice periods on the employee (beyond the statutory two weeks), requiring employer approval for resignation, or otherwise unreasonably restricting the right to leave are highly likely to be deemed void as contrary to public policy.

- Employer Conduct: Employers are expected to process resignations smoothly. Actions intended to unduly obstruct or prevent a valid resignation (e.g., through threats, intimidation, or unreasonable delays in administrative procedures) could potentially expose the employer to claims for damages based on tort law.

- No Damages for Resignation Itself: Since resignation is a legal right for indefinite-term employees (with proper notice), employers generally cannot claim damages from the employee simply because they chose to leave, even if it causes business inconvenience. Claims would typically only arise if the resignation involved separate breaches of duty (e.g., misuse of trade secrets, breach of specific contractual obligations unrelated to the act of resigning itself).

Restrictions Under Fixed-Term Contracts

The situation differs significantly for employees on fixed-term contracts (yūki koyō).

- Binding Nature: By definition, a fixed-term contract binds both parties for the agreed duration. Therefore, an employee seeking to resign before the contract term expires is generally considered to be breaching the contract.

- Mid-Term Resignation Requires "Unavoidable Reason": Under Civil Code Art. 628, mid-term termination by either party is permissible only if there is an "unavoidable reason" (yamu o enai jiyū). This standard is interpreted strictly by courts and typically requires circumstances like severe illness, significant family emergency (e.g., need for urgent caregiving), or potentially a fundamental breach of contract by the employer. Simply finding a better job offer elsewhere does not usually qualify. An employee resigning mid-term without such a reason could theoretically face a damages claim from the employer (though proving damages is often difficult).

- Statutory Limits on Contract Duration (LSA Art. 14): To prevent excessively long periods of restricted mobility, Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA) limits the maximum duration of fixed-term contracts. The general limit is 3 years. This can be extended to 5 years for employees with highly specialized knowledge/skills (as defined by Ministerial Ordinance) and for workers hired after reaching age 60. Contracts exceeding these statutory limits are generally considered indefinite-term contracts from the outset, or at least the term beyond the limit is invalid.

- The Critical Exception - Right to Resign After 1 Year (LSA Rider Art. 137): This is a crucial provision often overlooked. For any fixed-term contract with a duration exceeding one year, LSA Rider (Supplementary Provision) Art. 137 grants the employee the statutory right to resign at any time after the first anniversary of the contract's start date, by giving notice (likely the standard two weeks under Civil Code Art. 627(1)). They do not need an "unavoidable reason" to do so after the first year.

- Policy Tension: This provision was introduced as a compromise during reforms that extended the general maximum contract term from 1 year to 3 years. While the longer 3-year term was intended partly to encourage employers to invest more in training fixed-term staff, Rider Art. 137 significantly limits the employer's ability to ensure the employee remains for the full duration beyond the first year, potentially disincentivizing such investment for general employees on multi-year contracts.

Training Cost Repayment Agreements ("Clawbacks") and LSA Art. 16

A common scenario where resignation freedom becomes contentious involves employer-funded training. Companies may invest significantly in employee development – sending them for overseas studies (MBA, etc.), funding professional licenses (e.g., pilot training), or providing extensive specialized courses – often requiring the employee to sign an agreement committing to remain with the company for a certain period post-training. If the employee resigns before this period expires, the agreement typically requires them to repay all or part of the training costs.

These "clawback" agreements directly impinge on the employee's freedom to leave and are subject to strict scrutiny under LSA Article 16, which states:

"An employer shall not make a contract which fixes in advance either a sum payable to the employer in the case of breach of contract or an amount of indemnity for damages."

This provision prohibits employers from pre-determining financial penalties or liquidated damages that automatically become payable if an employee breaches their employment contract – with early resignation often being viewed as such a breach in the context of these agreements. The core legal question is whether a training cost repayment clause constitutes an illegal penalty under LSA Art. 16, or a legitimate agreement for the reimbursement of expenses incurred primarily for the employee's personal benefit (akin to an educational loan conditional on continued service).

When are Training Cost Repayment Agreements Enforceable?

Japanese courts do not automatically invalidate all training cost repayment agreements. Instead, they conduct a case-by-case analysis, examining the substance of the arrangement rather than just its form, focusing on whether the agreement represents a genuine reimbursement for value received by the employee or a disguised penalty designed to deter resignation. Key factors considered include:

- Nature and Purpose of the Training:

- General vs. Firm-Specific Skills: Training providing general, transferable skills (e.g., an MBA degree, a standard professional license like a large vehicle driver's license) is more likely to be seen as personally benefiting the employee, making repayment potentially justifiable. Conversely, training focused on highly company-specific procedures, products, or internal systems, or legally mandated safety training, is typically viewed as an employer operating expense, and repayment clauses are likely invalid penalties.

- Relationship to Job Duties: Training directly necessary for performing mandatory job duties leans towards being an employer cost.

- Voluntariness of Participation:

- Was the training genuinely optional for the employee's self-development, or was it effectively required or strongly expected by the employer as part of the job or for career progression within the company? If participation was compelled or practically unavoidable, the costs are more likely considered the employer's responsibility. True voluntariness supports the "employee benefit" argument.

- Tangible Benefit to the Employee:

- Did the employee receive a clear, lasting personal benefit beyond improved performance in their current role? Obtaining a recognized degree, professional certification, or qualification usable elsewhere strongly supports the validity of a repayment obligation. Training that merely enhances performance in the current specific job is less likely to justify a clawback.

- Reasonableness of the Post-Training Service Commitment Period:

- Is the length of time the employee must remain employed after the training to avoid repayment reasonable? Courts often look to the maximum fixed-term contract durations under LSA Art. 14 (3 or 5 years) as important benchmarks. Required service periods significantly exceeding these statutory limits are highly likely to be deemed unreasonably long and unenforceable. While shorter periods (e.g., 1-3 years) are more common, even these must be proportionate to the cost and benefit of the training.

- Reasonableness of the Repayment Amount and Structure:

- Scope of Costs: Is the repayment limited to the actual, direct expenses incurred by the employer for the training (e.g., tuition fees, specific travel costs)? Agreements requiring repayment of wages paid during the training period are generally considered invalid penalties under LSA Art. 16, as wages are payment for labor provided.

- Pro-Rata Reduction: Does the repayment amount decrease based on the length of time the employee serves after completing the training? A system where the obligation reduces incrementally over the commitment period (e.g., decreasing by 1/36th each month over a 3-year period) is viewed much more favorably than one requiring repayment of the full amount regardless of when the employee leaves during the commitment period. Lack of a reasonable pro-rata reduction strongly suggests a punitive intent.

Overall Assessment: Courts perform a holistic evaluation. An agreement is more likely to be upheld if it concerns voluntary training yielding significant, transferable benefits to the employee, the repayment is strictly limited to actual direct costs (excluding wages), the amount decreases reasonably over time, and the required service period is proportionate and generally within the bounds suggested by LSA contract duration limits. Agreements failing on multiple factors, particularly those involving mandatory training, firm-specific skills, repayment of wages, or long/unreduced repayment obligations, are very likely to be voided as violating LSA Art. 16.

Skill Formation Policy Context

The legal analysis of training cost repayment often intersects with broader policy considerations regarding skill formation. Economic theory suggests that rational employers are less likely to invest in general skills training (benefiting the employee in the wider labor market) unless they have some mechanism to recoup that investment, as employees could otherwise leave immediately after training to capitalize on their enhanced market value elsewhere. Training cost repayment agreements, when reasonably structured, can be seen as one such mechanism, potentially enabling employers to offer valuable general skills training they might otherwise forgo. This perspective suggests that overly strict prohibition of all repayment agreements could inadvertently reduce training opportunities for workers.

However, this must be balanced against the fundamental right to resign and change jobs. Unreasonable restrictions, even if intended to protect training investments, can unduly hinder labor mobility and employee autonomy. The legal framework, particularly LSA Art. 16 and the judicial factors outlined above, attempts to strike this balance by permitting repayment only where the arrangement genuinely reflects a shared investment in the employee's transferable skills under fair terms, rather than a penalty for exercising their freedom to leave.

Practical Implications for Employers in Japan

Companies employing staff in Japan should consider the following:

- Respect Resignation Rights: Understand the strong legal protection for resignation, especially the two-week notice rule for indefinite contracts and the statutory right to leave after one year for fixed-term contracts exceeding that duration. Avoid actions that could be construed as unlawfully obstructing an employee's departure.

- Limitations of Fixed Terms: Recognize that fixed-term contracts over one year provide limited protection against employee departure for the full term due to LSA Rider Art. 137.

- Drafting Training Cost Agreements Carefully: If utilizing training cost repayment agreements:

- Ensure participation is genuinely voluntary.

- Focus on training that provides clear, transferable benefits/qualifications to the employee.

- Clearly separate training costs from wages/living expenses during training.

- Limit repayment strictly to actual, direct, third-party costs (e.g., tuition, exam fees).

- Implement a reasonable pro-rata reduction schedule for the repayment obligation based on continued service post-training.

- Keep the required service commitment period reasonable, ideally not exceeding the LSA Art. 14 limits (3 or 5 years depending on the employee).

- Document the agreement clearly, explaining the terms and the voluntary nature.

- Seek legal advice to ensure the agreement is structured to maximize enforceability under LSA Art. 16 and relevant case law.

- Consider Alternatives: Explore other methods for retaining trained employees, such as retention bonuses payable after a certain period, vesting schedules for deferred compensation or stock options, or focusing on creating a positive work environment that encourages loyalty.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Freedom of Movement

Japanese employment law places a high value on an employee's freedom to choose their occupation and change jobs. While indefinite-term employees enjoy a broad right to resign with minimal notice, fixed-term contracts impose limitations, though these are themselves significantly curtailed by statutory provisions allowing resignation after one year for longer contracts.

Agreements seeking to recoup employer investments in training by requiring repayment upon early departure face strict scrutiny under the Labor Standards Act's prohibition on pre-determined penalties (LSA Art. 16). Enforceability depends heavily on demonstrating that the arrangement is a fair reimbursement for tangible, personal benefits voluntarily received by the employee, rather than a penalty designed to lock them into employment. Key factors include the nature of the training, voluntariness, the reasonableness of the repayment period, and the structure of the repayment amount (limited to actual costs, ideally with pro-rata reduction).

For businesses operating in Japan, attempting to unduly restrict employee departures through overly broad contractual clauses or punitive repayment schemes carries significant legal risk. A clear understanding of the applicable legal principles and careful structuring of any restrictive agreements are essential to balancing legitimate business interests with the legally protected freedom of employees to pursue their careers.

- Employee Dismissals in Japan: Membership vs. Job-Based Models

- Mind the Gap: Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees

- Post-Employment Non-Competes in Japan: Legal Tests & Drafting Tips

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Q&A on Resignation and Training Cost Agreements

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/roudoukijun/taishoku_traningcost.html