Freedom of Speech vs. The Right to Privacy: Japan's Supreme Court on Trespass in Residential Buildings

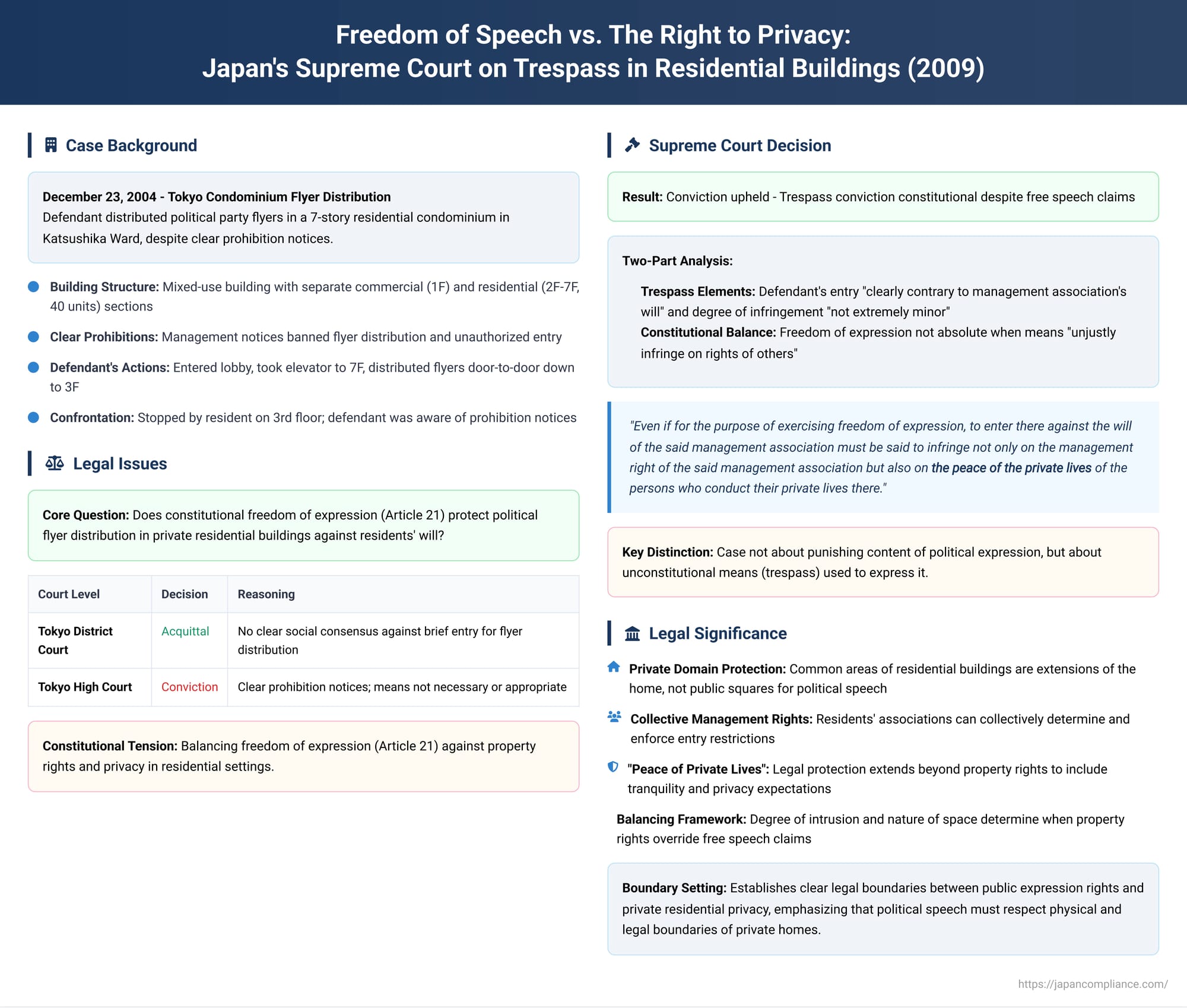

Does the constitutional right to freedom of expression, such as distributing political flyers, grant a person the right to enter a private apartment building against the explicit wishes of its residents? This question, pitting a fundamental democratic right against the equally fundamental rights to property and privacy, was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 30, 2009. The case forced the judiciary to draw a fine line, defining the physical and legal boundaries where political speech must yield to the sanctity of a private residence.

The ruling provides a crucial framework for understanding how Japanese law balances these competing interests. It affirms that while political speech is afforded the highest respect, the methods used to disseminate it cannot infringe upon the collective management rights of property owners and the personal right of residents to enjoy peace in their private lives.

The Facts of the Case: A Holiday Flyer Campaign

The case involved a defendant who, at the request of an acquaintance, set out to distribute political party flyers in a condominium in Katsushika Ward, Tokyo, on the afternoon of a public holiday, December 23, 2004.

The building in question was a seven-story, reinforced concrete condominium. The first floor contained commercial shops and offices, while the second floor and above consisted of 40 privately owned residential units. The entrances for the commercial and residential sections were completely separate.

The residential section's main entrance was a glass door leading into a lobby, or entrance hall. Inside this lobby were the residents' collective mailboxes, a notice board, and the window of the manager's office. At the back of the lobby, another glass door opened into the first-floor corridor, providing access to an elevator and stairs leading to the upper floors.

The management situation was clearly communicated. Near the main entrance, a sticker indicated the presence of security cameras. More importantly, the notice board in the lobby displayed two prominent notices from the residents' management association:

- One, on white paper, stated: "Posting of flyers, pamphlets, and other advertisements is strictly prohibited".

- Another, on yellow paper, read: "Entering the condominium grounds to post pamphlets, sell goods, etc., is strictly prohibited. Vendors with specific business appointments... must sign the 'Entry/Exit Logbook' at the manager's office...".

These notices were placed in a location where they would be easily seen by anyone entering the lobby for the purpose of distributing flyers.

Furthermore, the management association's board had passed a formal resolution prohibiting the distribution of all flyers, leaflets, and pamphlets—including in the collective mailboxes—with the sole exception of the official ward gazette. A building manager was typically on duty during weekday and Saturday morning hours, but the defendant's entry occurred on a public holiday when the manager was not present.

The defendant entered the main lobby, proceeded through the inner glass door, and took the elevator to the seventh floor. He then began distributing the political flyers by putting them directly into the mail slots of each apartment's front door, working his way down via the external stairwell. His actions were stopped by a resident who confronted him on the third floor. The court found that the defendant had been aware of the notices posted in the lobby when he entered.

The Journey Through the Courts: A Tale of Two Rulings

The defendant was charged with trespass. His case's journey through the judicial system revealed a deep conflict in how to evaluate such an act.

The Tokyo District Court, as the court of first instance, acquitted the defendant. Its reasoning was that for an entry to be a criminal trespass, it must be something that is not socially tolerated. The court found that, at the time, no clear social consensus had been established to criminalize the act of briefly entering the common areas of a residential building to distribute materials in individual door mail slots. While the entry was technically against the management's will, the court found that this will had not been communicated through "effective measures" that would convey the prohibition to a visitor at the time of entry.

The prosecutor appealed, and the Tokyo High Court overturned the acquittal and convicted the defendant. The High Court found that the notices clearly prohibited the distribution of all types of flyers, not just commercial ones, and that the defendant was aware of this. It asserted that measures like auto-locks or a constant guard presence are not required to prohibit entry by outsiders. The High Court concluded that the notices were an effective measure to communicate the prohibition of entry beyond the main lobby. It further reasoned that while the defendant's purpose—distributing political flyers—was legitimate, the means used were neither necessary nor appropriate, and thus the act's illegality was not negated. It also held that convicting for the act of trespass did not unduly infringe upon the public's right to know, as other means of distribution were available.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

The defendant appealed to the Supreme Court, which ultimately upheld the conviction, providing a definitive legal framework for analyzing such cases. The Court's reasoning was delivered in two distinct parts: a direct analysis of the crime of trespass and a constitutional analysis of the conflict with freedom of expression.

Part 1: The Trespass Analysis

The Court began by affirming that the defendant's actions constituted criminal trespass under Article 130 of the Penal Code. It determined this by looking at the totality of the circumstances, stating that "based on the structure and management status of the condominium, the situation within the entrance hall, the content of the aforementioned notices, and the purpose of the entry," the defendant's act was "clearly contrary to the will of the management association". The Court also found that the defendant recognized this fact.

Crucially, the Court rejected any notion that the intrusion was trivial. It emphasized that the defendant's actions went far beyond a simple entry into the main lobby. The trespass involved opening the inner door and entering the private corridors from the seventh floor down to the third. Given these facts, the Court concluded that "the degree of infringement of the legally protected interest cannot be said to be extremely minor".

Part 2: The Constitutional Analysis (Balancing Rights)

The Court then turned to the defendant's central claim: that a conviction for distributing political flyers violated his freedom of expression under Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Court began by acknowledging the paramount importance of this right, stating, "Freedom of expression must be respected as a particularly important right in a democratic society," and that distributing political flyers is an exercise of that freedom.

However, the Court immediately qualified this by noting that freedom of expression is not absolute. It can be subject to "necessary and reasonable restrictions for the public welfare," and even if an act is a means of expressing ideas, it is not permissible if it "unjustly infringes on the rights of others".

The Court framed the issue carefully: the case was not about punishing the content of the political expression. Rather, it was about the constitutionality of punishing the means used to express it—namely, trespassing on private property without permission.

In its most significant passage, the Court defined the rights that the defendant's actions infringed upon. The common areas of the condominium were not public spaces; they were places "where the residents of the said condominium conduct their private lives" and were managed as such by the residents' association. Therefore, the Court held:

"Even if for the purpose of exercising freedom of expression, to enter there against the will of the said management association must be said to infringe not only on the management right of the said management association but also on the peace of the private lives of the persons who conduct their private lives there."

Because the act infringed on both the collective property right of management and the individual right to privacy and peace, the Court concluded that punishing the trespass did not violate the Constitution.

Analysis and Implications: The Peace of Private Life

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision provides a nuanced resolution to a complex problem. It did not create a simple rule where property rights always trump free speech. Instead, it highlighted that the degree of intrusion and the nature of the space are paramount.

The fact that the defendant proceeded past the semi-public lobby and into the private residential corridors was a decisive factor. As some legal analysis suggests, had the defendant only placed flyers in the collective mailboxes in the main lobby, the court might have considered the infringement "extremely minor" and reached a different conclusion.

Furthermore, the Court's explicit protection of "the peace of the private lives of the persons" elevates the analysis beyond a simple, abstract property dispute. It recognizes that the common hallways of a residential building are an extension of the home, a buffer zone where residents have a reasonable expectation of privacy and tranquility. This reasoning moves the legal interest protected by trespass law from just the right to control property to include the concrete, personal right to be left alone in one's living space.

The decision confirms that in a multi-unit dwelling, which is in some sense a "socialized" space, the will of the residents is determined collectively through their management association, and this collective will, when clearly expressed, must be respected.

Conclusion

The 2009 Supreme Court ruling stands as a critical marker in Japanese law, clarifying the boundaries between public expression and private life. It establishes that while the distribution of political ideas is a cherished right, the exercise of that right must respect the physical and legal boundaries of a private home. The common areas deep within a residential building are not a public square. They are part of a private domain where residents' rights to manage their property and, more importantly, to enjoy the peace of their private lives, are legally protected, even from incursions made in the name of free speech.