Freedom of Recruitment vs. Individual Rights: The Landmark Mitsubishi Jushi Case in Japan

Judgment Date: December 12, 1973

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Labor Contractual Relationship Existence (Known as the Mitsubishi Jushi Case)

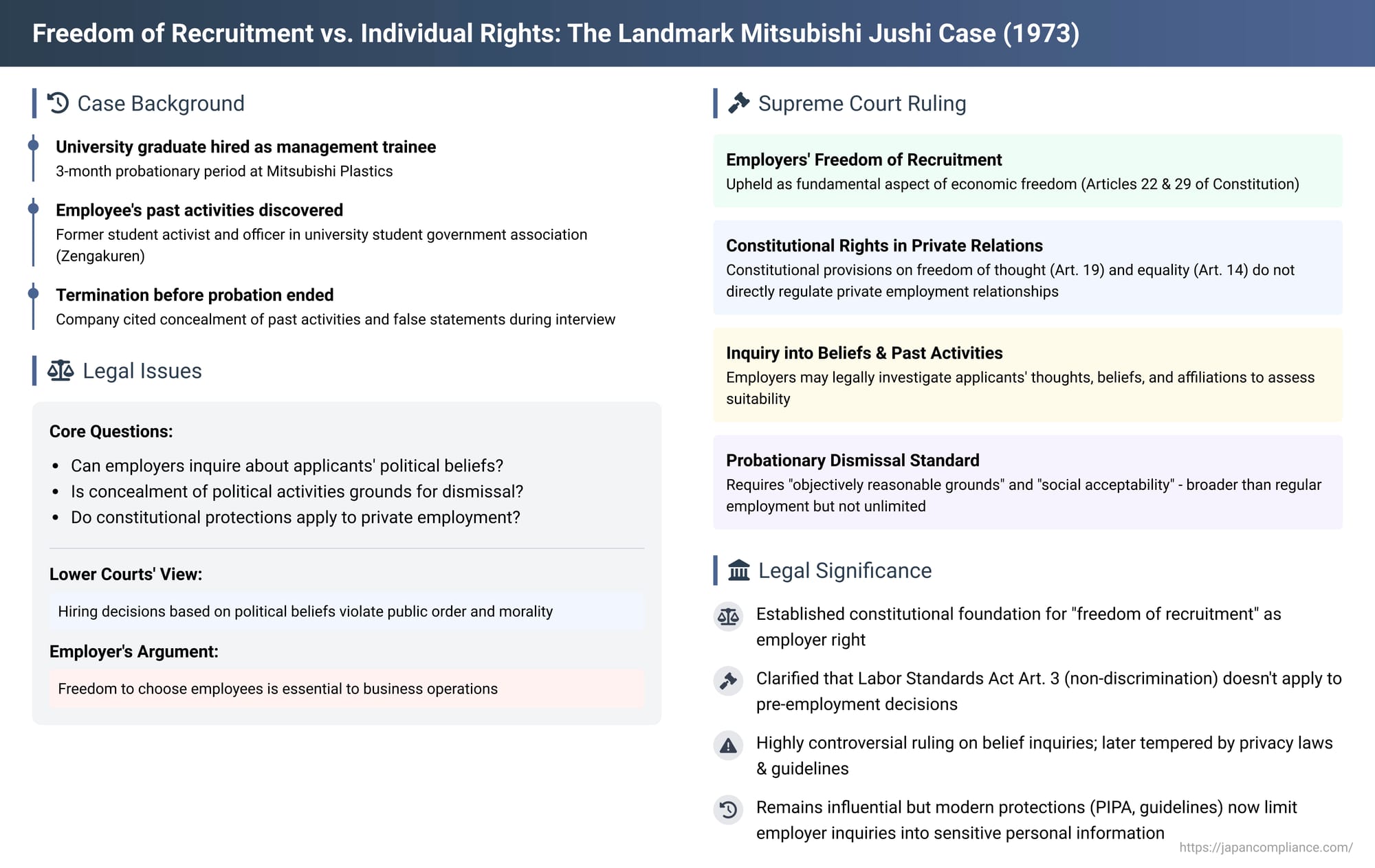

The extent to which employers can inquire into the personal beliefs and past affiliations of job applicants has long been a contentious issue, balancing the employer's freedom to choose its workforce against an individual's fundamental rights. In Japan, the Supreme Court's Grand Bench judgment in the Mitsubishi Jushi (Mitsubishi Plastics) case, delivered on December 12, 1973, stands as a landmark decision that profoundly shaped the legal understanding of "freedom of recruitment" and its interplay with constitutional protections.

Factual Background of the Mitsubishi Jushi Case

The case involved an individual, X, who, while a student at Tohoku University, successfully passed the recruitment examination for Company Y. Upon his graduation, Company Y hired him as a management trainee, stipulating a three-month probationary period. However, just days before this probationary period was due to expire, Company Y notified X that his full, permanent employment would be refused.

Company Y asserted several reasons for this refusal. It claimed that X had made false statements or concealed crucial information on the personal history declaration form submitted during the recruitment process and had also provided false answers during his interview. Company Y argued that X's actions constituted fraud under the Civil Code and demonstrated his unsuitability as a management trainee. The specific concealments at issue were X's past involvement in student activism, including his role as an officer in a university student self-government association (affiliated with a prominent national student federation, Zengakuren), and his prior service as an officer in a university co-operative. X had allegedly not disclosed these activities and, when asked during his interview, had falsely stated that he had not participated in student movements and had no interest in them.

Decisions of the Lower Courts:

- The Tokyo District Court (First Instance): This court characterized the refusal of full employment as an exercise of a reserved right to terminate the employment contract. It found that while X's disclosures might have lacked completeness, they were not fundamentally untrue, and there was no evidence of malicious intent. Consequently, the court ruled that the dismissal constituted an abuse of the employer's right and was therefore invalid.

- The Tokyo High Court (Second Instance): The High Court upheld the District Court's conclusion. It reasoned that an individual's thoughts and beliefs are inherently free, a freedom guaranteed by Article 19 of the Japanese Constitution. In situations where one party holds a superior position, such as an employer hiring a worker, this freedom should not be arbitrarily infringed. The High Court further noted that discrimination based on creed is prohibited by Article 14 of the Constitution and Article 3 of the Labor Standards Act. It opined that for ordinary commercial enterprises—unlike organizations with specific political or ideological leanings such as newspapers or certain schools—hiring individuals with particular political thoughts or beliefs would not inherently impede business operations. Therefore, the High Court concluded that compelling applicants to disclose matters related to their political thoughts or beliefs during entrance examinations was contrary to public order and morality (公序良俗 - kōjo ryōzoku). As such, applicants could not be disadvantaged for concealing such information. Company Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court, in a Grand Bench decision, overturned the High Court's ruling and remanded the case for further proceedings. Its judgment addressed several fundamental legal principles:

- Constitutional Rights and Private Relationships:

The Court clarified that constitutional guarantees of fundamental rights, such as freedom of thought and conscience (Article 19) and equality under the law (Article 14), are primarily designed to protect individuals against actions by the state or public entities. They do not directly govern relationships between private individuals. Applying these constitutional provisions directly, or even by analogy, to private interpersonal relations was deemed inappropriate by the Court.

However, the Court acknowledged that in private relationships where significant power imbalances exist, leading to potential infringements of basic freedoms or equality beyond socially acceptable limits, legal redress could be sought. This could occur through legislative measures or, in certain cases, through the appropriate application of general principles of private law, such as public welfare (Civil Code Article 1), public order and morality (Civil Code Article 90), or tort law provisions. This approach aims to balance private autonomy with the protection of fundamental interests. - Employer's Freedom of Recruitment (採用の自由 - Saiyō no Jiyū):

The Supreme Court firmly grounded the employer's freedom of recruitment in the constitutional guarantees of economic freedom, including the right to property and freedom to choose one's occupation (Articles 22 and 29). As part of their economic activities, employers possess the freedom of contract. This includes the freedom to decide whom to hire and under what conditions, unless specific laws impose restrictions.

Crucially, the Court stated that an employer's refusal to hire an individual because of that person's specific thoughts or beliefs is not inherently illegal. It reasoned that:- Article 14 of the Constitution (equality under the law) does not directly prohibit such actions by private employers.

- Article 3 of the Labor Standards Act, which prohibits discrimination based on creed in wages and other working conditions, applies to conditions after an employee is hired, not to the hiring decision itself.

- A refusal to hire based on an applicant's thoughts or beliefs cannot automatically be deemed a tort or a violation of public order and morality.

- Employer's Freedom to Investigate Applicants' Beliefs:

Flowing from the freedom of recruitment and the legality of refusing to hire based on thoughts or beliefs (in the absence of specific prohibitive laws), the Supreme Court concluded that employers are also legally permitted to investigate a job applicant's thoughts and beliefs. This includes requiring applicants to disclose information on such matters.

The Court acknowledged that such inquiries by employers, who generally hold a socially superior position to individual applicants, could potentially influence an applicant's freedom of thought and conscience. However, it maintained that, unless otherwise stipulated by law, such investigations are legally permissible acts by an employer.

Furthermore, the Court found it reasonable for employers to be concerned about whether a prospective employee might engage in behavior that could disrupt the smooth operation of the enterprise. Investigating an applicant's inclinations, thoughts, and past conduct to assess this risk was considered a rational aspect of business activity, particularly in the context of Japan's then-prevalent lifetime employment system, which emphasized mutual trust and the nature of employment as an ongoing human relationship extending beyond the mere provision of physical labor. - Legal Nature of the Probationary Period and Refusal of Full Employment:

The Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts' characterization of X's initial three-month employment as an employment contract with a reserved right of cancellation (解約権留保付雇傭契約 - kaiyaku-ken ryūho-tsuki koyō keiyaku). This means that the refusal to transition X to full, permanent employment at the end of the probationary period was legally considered a form of dismissal, rather than a simple refusal to enter into a new contract. - Limits on Dismissal During or at the End of Probation:

While acknowledging that a dismissal based on a reserved right of cancellation allows employers a broader scope of freedom than in cases of ordinary dismissal (i.e., dismissal of a regular, non-probationary employee), the Court stressed that this freedom is not unlimited.

The purpose of such a reserved right is to allow employers to make a final assessment of an employee's suitability (aptitude, character, abilities) after a period of observation, as it is often difficult to gather all necessary information during the initial recruitment stage.

Considering the protective intent of labor laws, the typical power imbalance between employers and employees, and the fact that an individual entering a probationary period often forgoes other employment opportunities with the expectation of permanent employment, the Court held that the exercise of this reserved right of termination is permissible only if:- There are objectively reasonable grounds for the dismissal.

- The dismissal is socially acceptable (justifiable in light of common societal norms).

This standard implies that if an employer, through investigations after hiring or observations during the probationary period, discovers facts that were not known (and could not reasonably have been expected to be known) at the time of initial hiring, and these facts, when objectively viewed, render the individual unsuitable for continued employment within that enterprise, then the reserved right to terminate may be exercised.

- Remand for Factual Re-evaluation:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its fundamental premise that it was illegal for Company Y to inquire into matters related to X's thoughts and beliefs. The case was therefore remanded to the High Court. The purpose of the remand was to:- Ascertain the precise facts regarding X's alleged concealment of his student activities and any false statements made.

- Examine the nature, manner, and extent of X's involvement in student movements, particularly whether any of his actions were illegal.

- Clarify X's motives and reasons for any concealment or misrepresentation.

- Based on these factual findings, determine the impact of X's conduct and past activities on his suitability as a management trainee for Company Y and, ultimately, to judge whether there were objectively reasonable and socially acceptable grounds for Company Y to refuse his full employment.

Analysis and Enduring Implications of the Mitsubishi Jushi Judgment

The Mitsubishi Jushi decision has had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese labor law, particularly concerning the freedom of recruitment and its boundaries.

- Constitutional Basis for Freedom of Recruitment:

A key contribution of the judgment was its articulation of the employer's freedom of recruitment as an element of the economic freedoms guaranteed by Articles 22 and 29 of the Constitution. This provided a strong constitutional underpinning for employers' prerogatives in hiring. This freedom encompasses decisions on hiring numbers, recruitment methods, candidate selection, contract terms, and, controversially, investigation of applicants. - Non-Applicability of Labor Standards Act Article 3 to Hiring:

The Court's confirmation that Article 3 of the Labor Standards Act (which prohibits discrimination based on creed, sex, social status, or family origin concerning wages, working hours, or other working conditions) does not apply to the act of hiring itself, but only to conditions after employment commences, became an established interpretation. - The Controversial Stance on Investigating Applicants' Beliefs:

The judgment's most debated aspect is its assertion that employers have a broad, legally permissible right to investigate and inquire into the thoughts, beliefs, and past affiliations of job applicants. The Court justified this by linking it to the freedom of recruitment and the perceived need for employers, especially under a lifetime employment model, to assess an individual's overall suitability and potential for harmonious integration into the company culture.

This aspect of the ruling drew immediate and sustained criticism from many legal scholars for several reasons:- Conflict with Fundamental Personal Rights: Critics argued that allowing such inquiries infringes upon an individual's freedom of thought and conscience (Constitution Article 19) and the right to privacy (implicitly protected under Article 13's guarantee of respect for the individual). They contended that an applicant's personal beliefs are often irrelevant to their ability to perform a job and are core to their personality, deserving protection even in private interactions.

- Contradiction with the "Dual Standard" Theory: In Japanese constitutional jurisprudence, there is a widely accepted "dual standard" (二重の基準論 - nijū no kijun ron) theory, which posits that spiritual and mental freedoms (like freedom of speech and thought) should receive a higher degree of protection and be subject to stricter scrutiny when restricted, compared to economic freedoms. Critics argued that the Mitsubishi Jushi judgment appeared to reverse this hierarchy by prioritizing the employer's economic freedom of recruitment over the applicant's freedom of thought.

- Neglect of the Applicant's Right to Livelihood: The ruling was also criticized for potentially undermining an individual's ability to secure employment and thus their right to livelihood (related to Constitution Article 25, the right to maintain wholesome and cultured living).

- Indirect Application of Constitutional Rights – A Limited Shield:

While the Supreme Court acknowledged the theoretical framework of indirectly applying constitutional rights to private relationships via general clauses of private law (like "public order and morality"), its practical application in this case offered little protection to X regarding inquiries into his beliefs at the hiring stage. The emphasis on employer's economic freedom and the perceived needs of the employment relationship effectively led to a non-application of constitutional protections for thought and creed in this specific context. - Societal and Legal Developments Since 1973:

It is crucial to note that the socio-legal landscape concerning privacy and information collection in employment has evolved significantly since the Mitsubishi Jushi judgment:- Governmental Guidelines: The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has issued guidelines (e.g., "Action Guidelines on the Protection of Personal Information of Workers," 2000) and the Employment Security Act (Article 5-4) and its accompanying guidelines now generally prohibit or strongly discourage employers from collecting sensitive personal information, including an applicant's thoughts and beliefs, unless directly relevant to the job.

- Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA): Japan's Personal Information Protection Act now designates information concerning a person's creed, religion, race, medical history, etc., as "special care-required personal information" (要配慮個人情報 - yō-hairyo kojin jōhō). The acquisition of such information generally requires the explicit consent of the individual (Article 20, Paragraph 2 of the PIPA, as amended). These legislative developments provide a more robust framework for protecting applicants' sensitive personal data than existed in 1973.

- Standard for Dismissal During Probation:

The judgment also provided an important clarification on the legal status of probationary employment, treating it as a contract with a reserved right of cancellation and setting the standard for dismissal as requiring "objectively reasonable grounds" and "social acceptability." This standard, while allowing more employer discretion than in ordinary dismissals, still provides a measure of protection to probationary employees.

Concluding Thoughts

The Mitsubishi Jushi Supreme Court judgment of 1973 remains a landmark ruling in Japanese labor law, particularly for its articulation of the employer's freedom of recruitment. However, its pronouncements on the permissibility of employers investigating applicants' thoughts and beliefs have been, and continue to be, highly controversial. While the core principles regarding freedom of recruitment and the non-applicability of LSA Article 3 to hiring decisions have endured, the broader societal and legal context has shifted towards greater protection of individual privacy and sensitive personal information. Subsequent legislation and administrative guidelines reflect this evolution, suggesting that the wide latitude apparently granted to employers in 1973 regarding inquiries into applicants' beliefs is now significantly qualified. The case underscores the enduring tension between managerial prerogatives and the fundamental rights of individuals in the employment sphere, a tension that continues to be navigated and reinterpreted in light of changing social values and legal frameworks.