Freedom of Expression vs. Reputation: Japan's Supreme Court on Prior Restraint of Publications (The Hoppo Journal Case)

Date of Supreme Court Decision: June 11, 1986

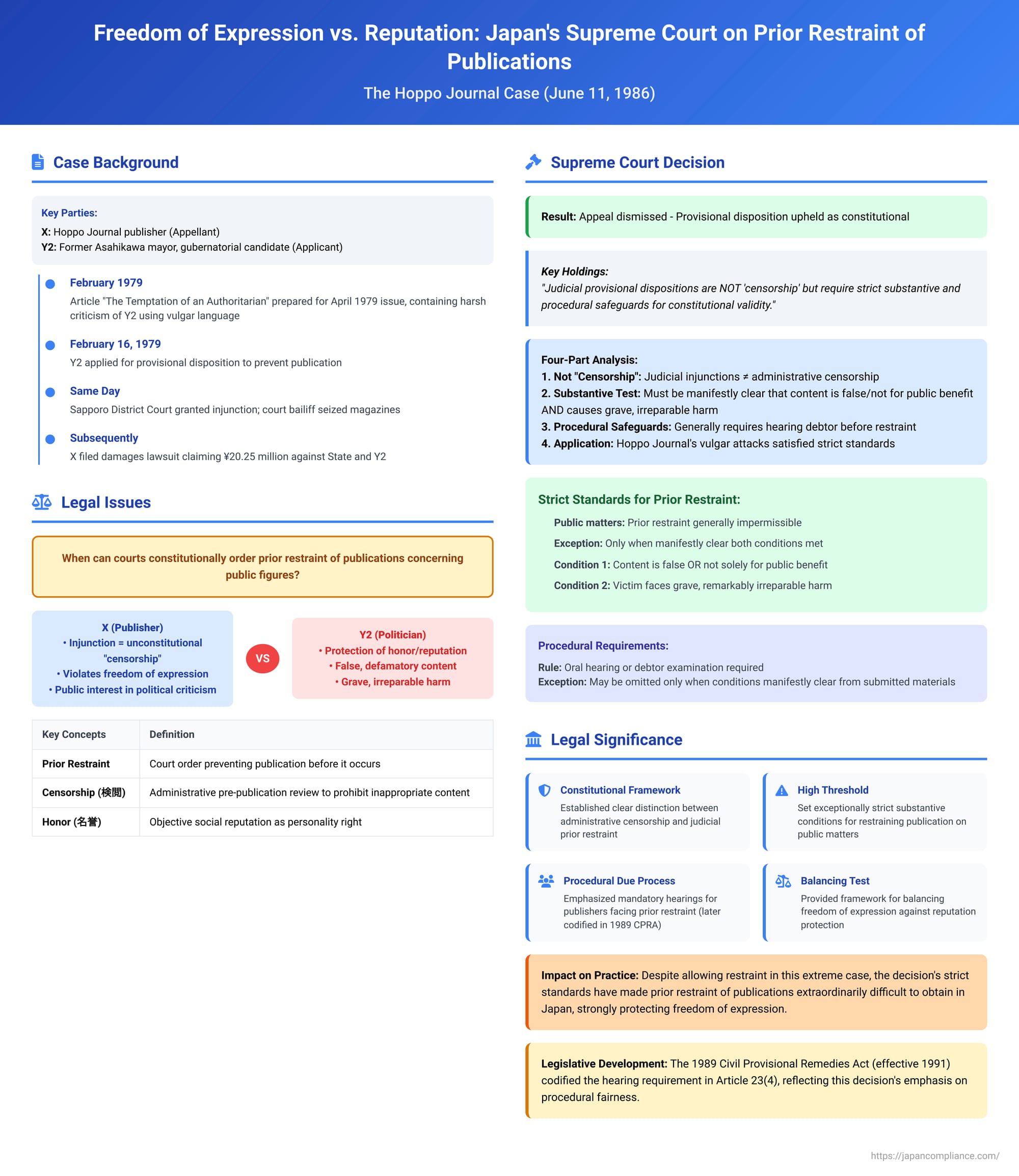

The conflict between the fundamental right to freedom of expression and the protection of an individual's reputation is a recurring theme in legal systems worldwide. In Japan, a landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court on June 11, 1986 (Showa 56 (O) No. 609), famously known as the "Hoppo Journal" case, addressed the constitutionality and permissible scope of "prior restraint" – specifically, a court-ordered provisional disposition (injunction) to prevent the publication of allegedly defamatory material. This judgment meticulously delineated the exceptionally strict substantive and procedural conditions under which such pre-publication censorship by judicial order could be deemed permissible.

The Factual Background: The "Hoppo Journal" Article and the Injunction

The case involved X, the company publishing the monthly magazine "Hoppo Journal," and Y2, a prominent political figure who was a former mayor of Asahikawa and, at the time of the events, was planning to run for the governorship of Hokkaido.

- The Controversial Article: X's representative had authored an article titled "The Temptation of an Authoritarian," which was slated for publication in the April 1979 issue of "Hoppo Journal." The article was scathingly critical of Y2, arguing that he lacked the requisite integrity, responsibility, and character to be governor. It employed extremely harsh, vulgar, and insulting language to describe Y2, including phrases such as "a boy adept at lies, bluff, and cheating," "cockroaches like Y2," "a verbal magician, a political street vendor hawking fraudulent goods," "a natural-born liar," "an ugly character hidden behind a beautiful mask," "an opportunist who would stop at nothing for his own benefit and advancement," "a mayor like a bitch's rear," and "Y2's true face is that of a swindler by day and a vicious thief by night, like Dozan the Viper." The article further alleged that Y2 was solely focused on self-preservation and electoral gain, pursued populist policies recklessly, engaged in self-promotion rather than public service, was adept at influence-peddling, had illicit ties with specific businesses for personal enrichment, allowed corruption to flourish while skillfully evading arrest, and that his gubernatorial candidacy was aimed at seizing power for personal aggrandizement.

- The Provisional Disposition (Injunction): On February 16, 1979, Y2's lawyers applied to the Sapporo District Court for a provisional disposition against X and A Printing Company. Citing the need to prevent infringement of Y2's right to honor (reputation), they sought an order for the court bailiff to take custody of the printed copies of the magazine and to prohibit any further printing, binding, sale, or distribution of the issue containing the article (unless the article was removed).

On the very same day, a judge of the Sapporo District Court granted the provisional disposition as requested. It was not definitively established in the subsequent main lawsuit whether an oral hearing or an examination of the debtor (X) had been conducted prior to this order being issued. The court bailiff executed the order on the same day, seizing the magazines. - X's Damages Lawsuit: X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y (the State, for the actions of the judge and bailiff) and Y2 (and one other individual), claiming damages of ¥20.25 million (reduced from an initial claim of ¥30.50 million). X alleged abuse of official authority by the judge and bailiff and asserted that the application for the provisional disposition itself was illegal. X's claim for damages was dismissed by both the court of first instance and the appellate court, leading X to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Holdings

The Supreme Court (Grand Bench) dismissed X's appeal, finding the original provisional disposition to be constitutionally permissible under the specific and extreme circumstances of the case. Its judgment laid out crucial principles:

Part I: Prior Restraint by Court Order is NOT "Censorship" (検閲 - ken'etsu)

X argued that the pre-publication injunction constituted "censorship," which is absolutely prohibited by Article 21, Paragraph 2 of the Japanese Constitution. The Supreme Court rejected this argument.

- It defined "censorship" as an action by an administrative authority that involves a comprehensive and general review of the content of expressions before publication, with the aim of prohibiting the publication of those deemed inappropriate. This aligns with the Court's earlier definition in another landmark case (Supreme Court Grand Bench decision, December 12, 1984, concerning customs inspection of imported materials).

- The Court distinguished judicial provisional dispositions (injunctions) from such administrative censorship. It reasoned that a provisional disposition for prior restraint:

- Is issued by a judicial court, not an administrative body.

- Arises from an individual dispute between private parties based on a specific application.

- Involves the court adjudicating the existence of a private law right to be preserved (e.g., the right to honor) and the necessity of such preservation.

- It is not a general pre-publication review system operated by the state as its own objective.

Therefore, the Court concluded that the provisional disposition issued against "Hoppo Journal" did not fall under the definition of "censorship" prohibited by Article 21(2).

Part II: Substantive Conditions for Permissible Prior Restraint of Publication (Especially Concerning Public Matters/Figures)

While not "censorship," the Court acknowledged that any form of prior restraint on expression is a serious matter under Article 21, Paragraph 1 (guaranteeing freedom of expression). It set forth very strict substantive conditions for its permissibility, particularly when the expression concerns public matters or figures:

- Protection of Honor: A person whose honor (名誉 - meiyo), defined as their objective societal reputation and an人格権 (jinkakuken – personality right), is unlawfully infringed can seek remedies including damages, measures to restore reputation, and, crucially, an injunction to stop ongoing or prevent future infringement.

- Clash with Freedom of Expression: When alleged defamation occurs through speech or publication, the individual's right to honor clashes with the freedom of expression. This requires a careful balancing, especially considering the vital role of free expression (particularly on public matters) in a democracy.

- General Rule Against Prior Restraint for Public Matters: For publications concerning the evaluation or criticism of public officials or candidates for public office (which are generally matters of public concern), prior restraint is, as a rule, not permissible. This is because such expressions have high societal value and are specially protected under the Constitution.

- Strict and Narrow Exception: Prior restraint in such cases is permissible only in exceptional circumstances where it is manifestly clear (明白 - meihaku) that both of the following conditions are met:

- (a) The content of the expression is false, OR it is not solely for the public benefit (専ら公益を図る目的 - moppara kōeki o hakaru mokuteki); AND

- (b) The victim is likely to suffer grave and remarkably irreparable harm (重大にして著しく回復困難な損害 - jūdai ni shite ichijirushiku kaifuku konnan na songai).

The Court reasoned that if these stringent conditions are met, the value of the expression is clearly subordinate to the victim's honor, and the necessity for an injunction as an effective remedy is affirmed.

Part III: Procedural Safeguards for Prior Restraint Injunctions (Provisional Dispositions)

Recognizing the significant chilling effect of prior restraint, the Court also established important procedural safeguards:

- Inadequacy of Standard Summary Procedures: For provisional dispositions seeking prior restraint of expression on public matters, the usual summary procedures (which under the old Code of Civil Procedure did not mandate a hearing and allowed proof by a prima facie showing – 疎明 - somei) are insufficient to adequately protect freedom of expression.

- Principle of Holding a Hearing: As a rule, an oral hearing or an examination of the debtor (the publisher or author) must be conducted before issuing such a provisional disposition. This is crucial to provide the publisher an opportunity to present their case, particularly to offer evidence and arguments regarding the truthfulness of the content and its purpose being solely for the public benefit.

- Strict Exception to the Hearing Requirement: An oral hearing or examination of the debtor may be omitted only in exceptional cases where, based on the materials submitted by the creditor (the applicant for the injunction), it is manifestly clear that the stringent substantive conditions for prior restraint (as outlined above: falsity/no public benefit AND grave/irreparable harm) are met.

- The rationale for this narrow exception is that if these conditions are so overwhelmingly obvious from the outset, affording the debtor an opportunity to be heard would not change the outcome, and thus the lack of a hearing would not cause them actual prejudice. Furthermore, the debtor still has avenues for redress, such as filing an objection to the provisional disposition and seeking a stay of its execution.

Part IV: Application of these Principles to the Hoppo Journal Case:

Applying these newly articulated standards, the Supreme Court concluded:

- Public Matter: The article concerned Y2, a political figure and candidate for public office, and therefore pertained to matters of public concern.

- Substantive Justification for Restraint: However, the Court found that the article's content and style, replete with vulgar and insulting personal attacks, made it manifestly clear that it was not solely for the public benefit and that it lacked truthfulness. Given the large planned print run (25,000 copies for the first printing) and the impending gubernatorial election (less than two months away), Y2, as a candidate, was likely to suffer grave and remarkably irreparable harm from the article's publication. Thus, the Court held that the substantive requirements for prior restraint were satisfied.

- Procedural Justification (Even if No Hearing Occurred): Regarding the procedure, while it was not definitively established whether X (the publisher) had been heard before the injunction was issued, the Supreme Court found that even if no hearing had occurred, there was no constitutional deficiency. This was because the conditions for the exception to the hearing requirement were met: the lack of public benefit and the falsity of the article's contents were deemed "manifestly clear" from the submitted materials and the nature of the article itself.

Therefore, the Court concluded that the original provisional disposition order against "Hoppo Journal" was constitutionally valid, both substantively and procedurally, under these highly specific and egregious circumstances.

Supplementary Opinions

Several justices offered supplementary opinions:

- Justice Masami Ito elaborated on why prior restraint by courts is not "censorship" and discussed the stringent standards for its application.

- Justice Susumu Ohashi (joined by Justice Keiji Maki) emphasized that the Sapporo District Court could have taken into account notorious facts, such as prior similar injunctions issued against X concerning articles about Y2, where X had been given an opportunity to be heard (a debtor examination). This suggested that X was not entirely unfamiliar with the legal scrutiny of its publications concerning Y2.

- Justice Masataka Taniguchi argued for an "actual malice" standard (i.e., knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth) as a requirement for prior restraint in cases involving public figures. He found that X clearly exhibited actual malice in this instance, and therefore, dispensing with a hearing was not unconstitutional.

Impact of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (1989) on Hearing Requirements

It is important to note that this Supreme Court decision was rendered under the old Code of Civil Procedure. Subsequently, the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA) was enacted in 1989 and came into effect in 1991. This Act significantly reformed provisional remedy procedures in Japan.

- "All Decision-Based" System: The CPRA adopted an "all decision-based" system (オール決定主義 - ōru kettei shugi), meaning that all provisional remedy orders are issued through a "decision" (決定 - kettei) procedure rather than a full "judgment" (判決 - hanketsu) procedure, even if oral arguments are held.

- Codification of Hearing Requirement: Crucially, Article 23, Paragraph 4 of the CPRA now explicitly mandates that, as a rule, an oral hearing or an examination of the debtor (at which the debtor can be present and make statements) must be held before a "provisional disposition to determine a provisional status" (仮の地位を定める仮処分 - kari no chii o sadameru karishobun), such as an injunction, can be issued. This provision essentially codifies the principle of procedural due process that the Supreme Court emphasized in the Hoppo Journal decision.

- Exception to Hearing under CPRA: However, CPRA Article 23, Paragraph 4 also contains a proviso: such a hearing or examination may be omitted if holding it would likely make it impossible to achieve the purpose of the provisional disposition (e.g., if there's a risk the debtor would preemptively act to frustrate the injunction if notified of a hearing).

- Hoppo Journal Principles Still Relevant: Despite the codification, the general principles established in the Hoppo Journal case regarding the high threshold for prior restraint and the fundamental importance of providing the publisher an opportunity to be heard remain highly influential. Even under the CPRA, in urgent cases involving imminent publication, courts endeavor to conduct swift debtor examinations, sometimes even resorting to summoning the debtor by telephone for a hearing on the same or the next day. The spirit of Hoppo Journal, demanding careful procedural fairness in prior restraint cases, continues to guide practice.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1986 Hoppo Journal decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese constitutional law concerning freedom of expression and the limits of prior restraint. It established exceptionally strict substantive criteria (manifest falsity or lack of public benefit, coupled with grave and irreparable harm) and emphasized the procedural necessity of hearing the publisher before issuing a pre-publication injunction, albeit with a narrow exception for cases where the deficiencies are overwhelmingly clear. While the procedural landscape has since been updated by the Civil Provisional Remedies Act, which explicitly mandates debtor hearings for most injunctive provisional dispositions, the Hoppo Journal case's robust defense of free expression and its cautious approach to prior restraint continue to shape judicial practice in Japan. It stands as a powerful affirmation that prior restraint of publication, particularly on matters of public concern, is a remedy of last resort, to be granted only under the most compelling and clearly evidenced circumstances.