Fraud in the Black Market: A Japanese Ruling on Crime and "Illegal Cause"

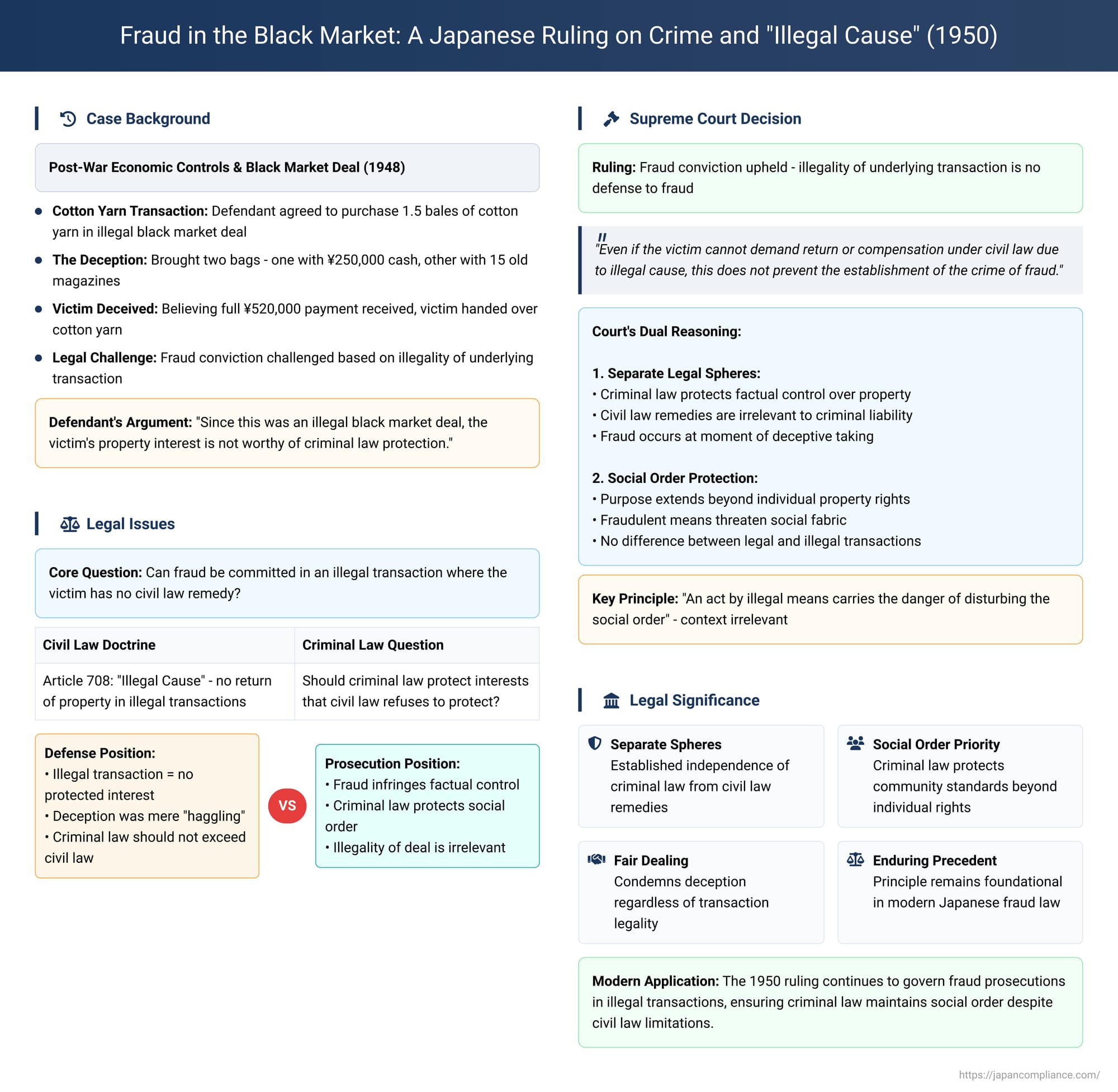

Imagine two parties engage in an illegal transaction—a black-market deal, for example, that violates economic control laws. One party uses deception to trick the other into handing over goods without receiving proper payment. Can the defrauded party, who was also participating in an illegal act, be considered a victim of criminal fraud? And can the perpetrator be punished for fraud, even if the victim, due to the illegality of the deal, has no legal right to sue in a civil court to get their property back?

This fascinating conflict, which pits criminal law against civil law, was the subject of a foundational ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 4, 1950. The case, arising from a post-war black-market deal for cotton yarn, established the enduring principle that the illegality of an underlying transaction is no defense to the crime of fraud. The Court's decision affirmed that the purpose of criminal law is not just to protect private rights, but to maintain the broader social order.

The Civil Law Background: The "Act for an Illegal Cause" Doctrine

To understand the case, one must first be familiar with a key principle in Japanese civil law: the doctrine of "act for an illegal cause" (fuhō gen'in kyūfu), outlined in Article 708 of the Civil Code. This article states that a person who provides property or services for a cause that is illegal or contrary to public policy cannot later demand its return in court.

Classic examples include money paid to a mistress to maintain the illicit relationship or funds provided to finance a crime. In such cases, the civil law essentially washes its hands of the matter. It refuses to assist the person who initiated the illegal transfer, with the result that the recipient gets to keep the property. This doctrine raised a critical question for the criminal law: if the civil law refuses to protect such a property interest, should the criminal law step in?

The Facts of the Case: A Black-Market Deal Gone Wrong

The case took place in the chaotic post-war economy of 1948, which was governed by strict economic control regulations. The defendant had agreed to purchase one and a half bales of cotton yarn from the victim in what was effectively an illegal black-market transaction.

The defendant went to the victim's home to pay the outstanding balance of 520,000 yen. He brought two bags, giving the impression that they contained the full cash amount. In reality, one bag contained 250,000 yen, while the other was filled with 15 old magazines. Deceived by this ruse into believing he had been paid in full, the victim handed over the cotton yarn to the defendant.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of fraud. On appeal, his defense lawyer argued that the conviction was improper. He contended that because the transaction was an illegal black-market deal, the victim's property interest was not worthy of protection by the criminal law. He further claimed that the defendant's deception was merely a form of "haggling" (kakehiki) that is inherent in such illicit dealings and did not rise to the level of criminal fraud.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Fraud is Fraud, Regardless of Context

The Supreme Court forcefully rejected the defendant's arguments and upheld the fraud conviction. The Court's judgment provided two distinct and powerful justifications for why the illegality of the underlying deal was no defense.

Reasoning 1: Criminal Law Protects Factual Control, Not Civil Law Claims.

First, the Court separated the spheres of civil and criminal law. It ruled that the crime of fraud is established when a perpetrator uses deception to infringe on the victim's "right of control over the... property". The Court stated that even if the victim's delivery of the property was based on an "illegal cause" and they "cannot demand its return or compensation for damages under civil law, this does not prevent the establishment of the crime of fraud". In essence, the immediate, factual infringement on the victim's possession at the moment of the fraudulent act is what constitutes the crime, regardless of what legal remedies might (or might not) be available to the victim later.

Reasoning 2: Fraud Disturbs the Social Order.

Second, the Court articulated a broader, policy-based justification. It declared that the purpose of punishing crimes like fraud extends beyond protecting the individual victim's property. The Court explained:

"The reason that a crime which has as its essence the infringement of another's property rights, such as the crime of fraud, is punished is not solely for the protection of the victim's property rights, but also because an act by such illegal means carries the danger of disturbing the social order."

The Court reasoned that from the perspective of maintaining social order, there is "no difference whatsoever" between fraudulent means used in a black-market deal and those used in a legitimate transaction. Deception as a means of acquiring property is inherently harmful to the fabric of society, and the criminal law must condemn it regardless of the context.

Analysis: A Continuing Debate on the Role of Criminal Law

The Supreme Court's 1950 decision reflects a pragmatic choice to prioritize the condemnation of fraudulent conduct and the maintenance of public order over a perfectly unified legal theory between civil and criminal law. This approach, while the settled law in Japan, continues to be the subject of scholarly debate.

- The "Separate Spheres" Approach: The Court's ruling is a classic example of the "separate spheres" theory, which holds that civil and criminal law have different goals and can operate independently. Civil law is concerned with private remedies, while criminal law is concerned with public order and crime prevention. The fact that a private remedy is unavailable does not mean a public wrong should go unpunished.

- The "Unified Legal Order" Critique: Some scholars critique this approach, arguing it creates an incoherent legal system. If one branch of the law (civil) declares a property interest to be unworthy of protection, it is contradictory for another branch (criminal) to then punish someone severely for infringing that same interest.

- A Reconciling View - The "Protected Pre-Transfer Right": A more nuanced theory attempts to reconcile these positions. It argues that while Civil Code Article 708 bars a claim for the return of property after an illegal transfer, it does not mean that the victim's right to control their property before the transfer is unprotected. The crime of fraud is an infringement on this valid, pre-existing right of possession and disposition. At the moment of the deception, the victim is still the rightful possessor of the property, and this possession is fully protected by the criminal law.

Conclusion: A Pragmatic and Enduring Precedent

The 1950 Supreme Court decision established a firm and lasting principle in Japanese jurisprudence: the illegality of a transaction is no shield against a charge of fraud. The ruling reflects a clear policy choice to condemn deception as a means of acquiring property, regardless of the context.

The Court's two-pronged justification—that fraud is both an immediate infringement on a victim's factual control over their property and a broader harm to the social order—has provided a robust foundation for prosecuting fraud even in the gray and black markets of the economy. The decision ensures that the criminal law stands not just as a tool to protect legitimate private property rights, but as a guardian of the basic rules of fair dealing that are essential for a stable society.