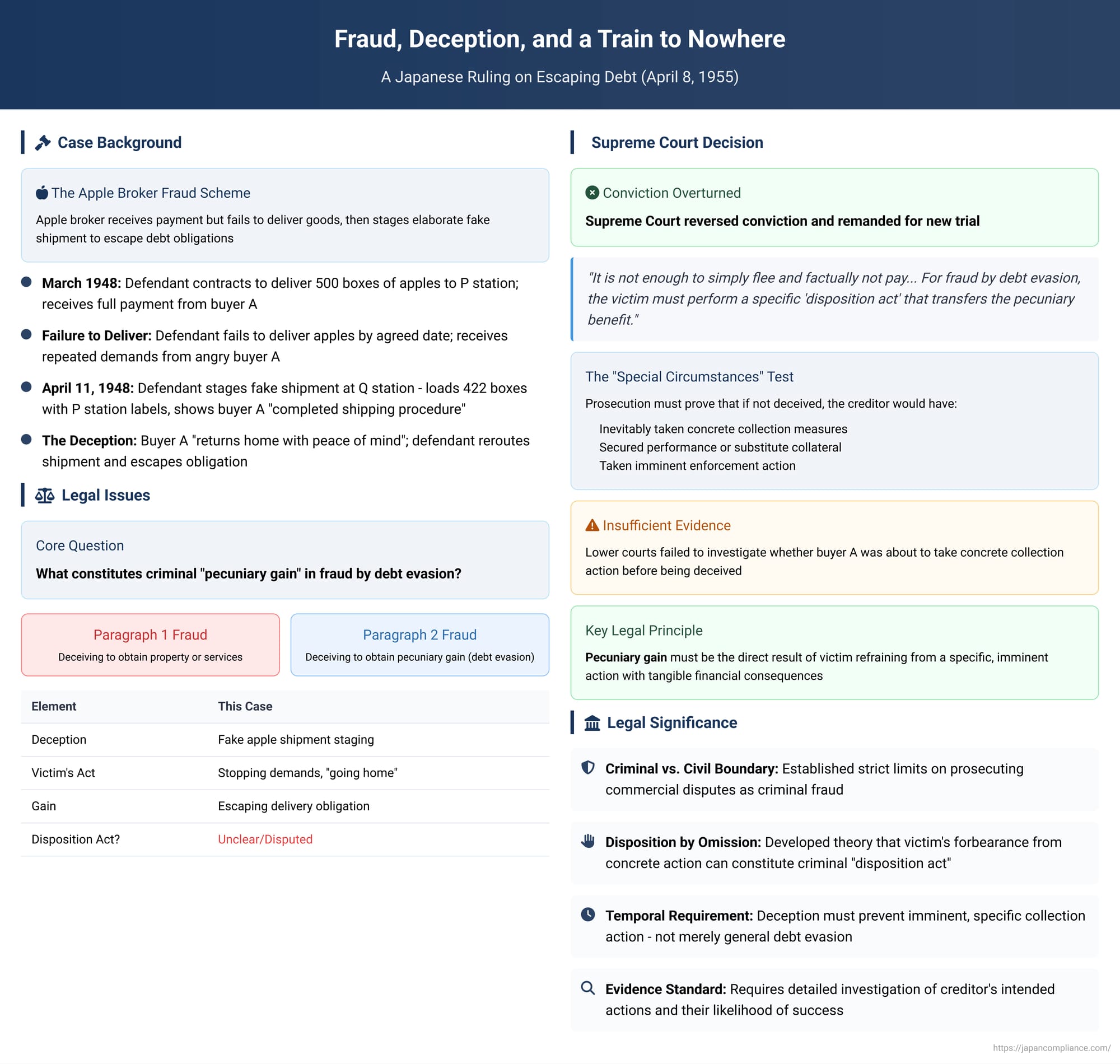

Fraud, Deception, and a Train to Nowhere: A Japanese Ruling on Escaping Debt

Imagine a supplier who has been paid for goods but has failed to deliver them. When the client rightfully demands performance, the supplier, having no intention of fulfilling the contract, stages an elaborate fake shipment. They load boxes onto a train, attach the correct shipping labels, and show this to the client, who, satisfied that the goods are finally on their way, leaves with peace of mind. The supplier then reroutes the shipment and disappears. Is this deceptive act criminal fraud? Or is it merely a breach of contract, a matter for the civil courts?

This question, which explores the fine line between a commercial dispute and a criminal act, was the subject of a foundational ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 8, 1955. The Court's decision dissected the anatomy of fraud for pecuniary gain, establishing a strict and enduring test for what it means to criminally "escape" a debt through deception.

The Facts: The Apples That Never Arrived

The defendant in the case was an apple broker. In March 1948, he entered into a contract with a buyer, A, to deliver 500 boxes of apples to P station by a certain date. He received payment in full from A but then failed to make the delivery.

After receiving repeated demands from the rightfully angry buyer, the defendant, having no intention of actually fulfilling the contract, devised a plan. On April 11, he led A to Q station. There, he had an associate, C, load 422 boxes of apples onto a freight car and attach shipping labels addressed to P station. He presented this scene to A, making it appear "as though the procedure for shipping 500 boxes of apples to P station was complete and all that was left was to await their arrival". Deceived by this elaborate charade, A "returned home with peace of mind". The defendant, having successfully placated his creditor, then rerouted the shipment and never completed his delivery, thereby escaping his contractual obligation.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of fraud. The lower High Court reasoned that the entire series of acts, from the fake shipment to the final failure to deliver, constituted a single criminal fraud, which was completed when the defendant succeeded in escaping his obligation. The defendant appealed, arguing that the victim, A, never performed a specific "disposition act" that transferred a financial benefit to him.

The Legal Framework: The Two Types of Fraud

The case required the Court to clarify the requirements of "2nd-paragraph fraud." The Japanese Penal Code distinguishes between two types of fraud under Article 246:

- Paragraph 1 Fraud: Deceiving a person to obtain property or services. This is the most common form of fraud.

- Paragraph 2 Fraud: Deceiving a person to obtain a pecuniary gain (zaisan-jō futō no rieki). This includes intangible benefits, such as the cancellation or evasion of a debt.

The defendant's act—escaping his obligation to deliver the apples—fell into the second category. The key legal question was what, precisely, a victim must do for a perpetrator to have criminally "obtained" this type of pecuniary gain.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Correction: A Stricter Test for Harm

The Supreme Court rejected the High Court's simple reasoning. In a landmark decision, the Court ruled that for the crime of fraud by debt evasion to be established, it is "not enough to simply flee and factually not pay". Merely tricking a creditor into "returning home with peace of mind" is insufficient.

The Court held that a conviction for 2nd-paragraph fraud requires that the victim be deceived into performing a "disposition act" (shobun kōi)—a conscious act that results in the transfer of the pecuniary benefit. The Court found that the trial court record was unclear on what disposition act the victim A had performed.

The Court then established a new, much stricter test. It ruled that simply causing a creditor to temporarily stop making demands is not a sufficient pecuniary gain for fraud. For the crime to be established, the prosecution must prove that "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō) existed.

This test requires showing that:

"...if the creditor had not been deceived, they would have, through their demands, inevitably taken some concrete measure such as securing the performance of all or part of the debt, or obtaining some substitute for it or collateral to secure it."

In other words, the fraud is complete only if the perpetrator's lie directly causes the creditor to refrain from taking an imminent and concrete collection action that they otherwise would have taken. The "pecuniary gain" is not the general evasion of the debt, but the specific, tangible benefit of escaping that concrete enforcement action.

Because the lower courts had not conducted the necessary investigation to determine if such "special circumstances" existed in this case—that is, whether A was on the verge of taking a specific legal or physical action to secure his apples or money before being duped by the fake shipment—the Supreme Court found the proceedings to be incomplete. It overturned the conviction and remanded the case for a new trial under this stricter standard.

Analysis: The Meaning of "Pecuniary Gain"

The Supreme Court's 1955 ruling provides a crucial limiting principle on the potentially vast scope of 2nd-paragraph fraud. It prevents the criminal law from being used to prosecute every lie told in a commercial dispute.

The decision clarifies that the "pecuniary gain" must be more than just buying time or temporarily placating an angry creditor. The gain must be the direct result of the victim being induced to perform—or, critically, to refrain from performing—a specific act that has tangible financial consequences. The court is looking for a concrete loss of opportunity for the victim. For example, if a creditor arrives with a moving truck to repossess collateral and is tricked into leaving by a false promise of payment, the debtor has committed fraud because they have evaded the concrete, imminent action of repossession. But if the creditor simply calls on the phone and is put off with a lie, the "special circumstances" test might not be met.

The ruling is also a key case in the development of the theory of the "disposition act." By requiring that the victim refrain from a concrete, imminent action, the Court gives substance to the idea of a "disposition by omission." The creditor, by relying on the deception, makes a conscious decision to forego an action they would otherwise have taken, and this forbearance is the "disposition act" that completes the crime.

Conclusion: Defining the Contours of Economic Fraud

The 1955 "fake apple shipment" case is a foundational decision in Japanese fraud law. It established that to be guilty of fraud for escaping a debt, it is not enough to simply tell a lie that makes a creditor go away for a while. The deception must be shown to have directly caused the creditor to abandon an imminent and concrete collection action that would have otherwise occurred.

This "special circumstances" test ensures that the serious charge of fraud is reserved for deceptions that cause a real, tangible loss of opportunity for the victim. It maintains a crucial boundary between criminal fraud and the ordinary, non-criminal evasions and delays that can occur in commercial disputes, ensuring that the power of the criminal law is focused on acts that cause genuine and demonstrable financial harm.