Fraud by Punctuality? A Japanese Ruling on the Crime of Getting Paid Too Soon

Imagine a contractor has completed a project and is legally entitled to a large payment from a client. To pass the final inspection and get that payment now, rather than waiting weeks or months for a full review of a minor issue, the contractor submits some forged paperwork. They receive the exact amount of money they were owed under the contract, just earlier than they might have otherwise. Have they committed the crime of fraud? Can simply accelerating a payment one is already entitled to constitute the "property damage" required for a criminal conviction?

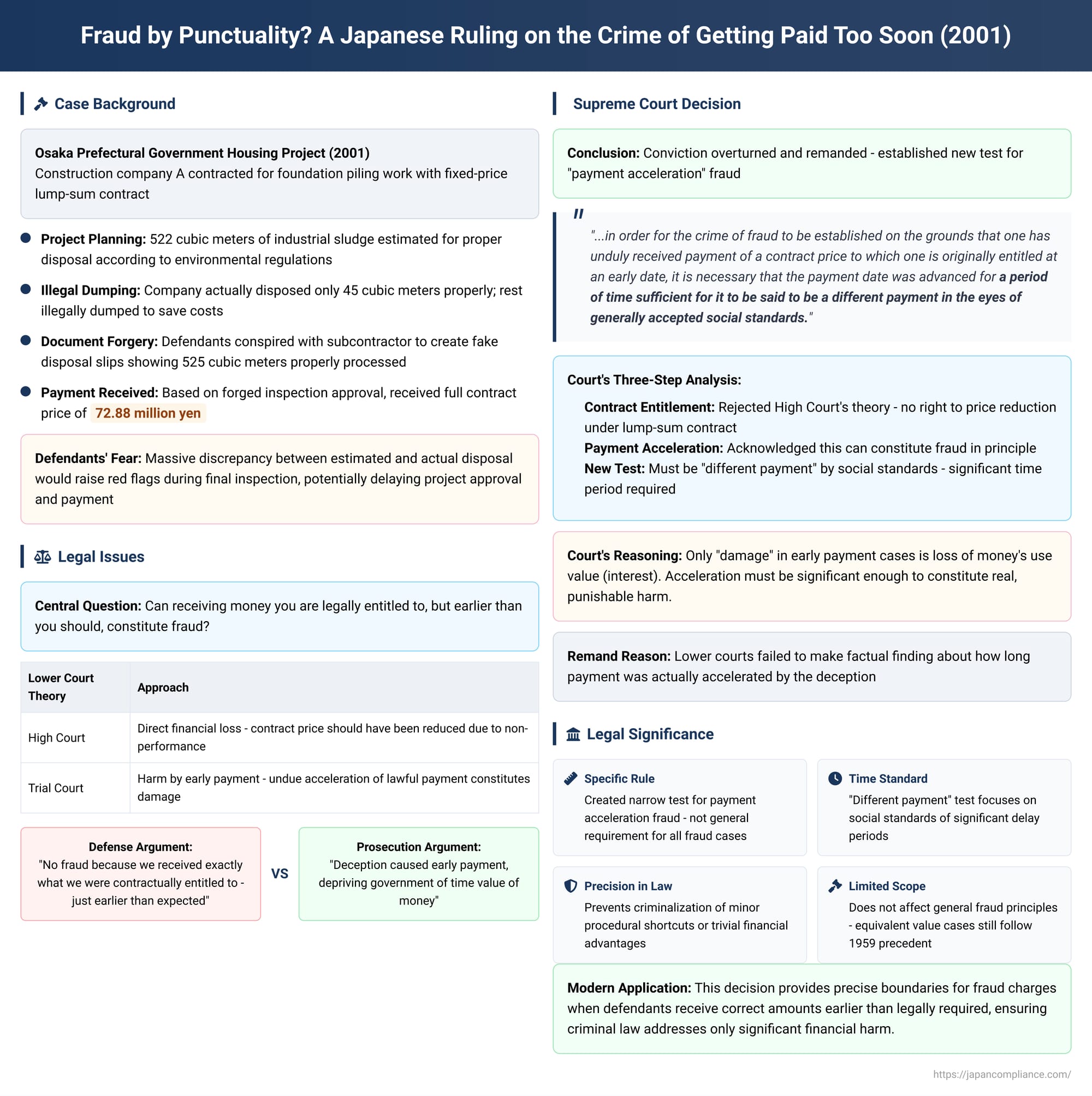

This subtle but important question was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 19, 2001. The case, involving a major public works project and forged sludge disposal slips, forced the Court to define the precise boundary between a procedural shortcut and a punishable property crime. In its ruling, the Court established a new and specific test for determining when getting paid too soon becomes fraud.

The Facts: The Construction Project and the Forged Slips

The case involved a construction company, A, which had a fixed-price, lump-sum contract with the Osaka Prefectural Government for foundation piling work on a high-rise housing project. The defendants were two employees of company A who were managing the site.

The project plan estimated that about 522 cubic meters of industrial sludge (odei) would be produced and would need to be properly disposed of according to environmental regulations. However, in reality, the company only disposed of about 45 cubic meters properly; the rest was illegally dumped to save costs.

The defendants feared that this massive discrepancy between the estimated and actual disposal amounts would raise red flags during the final inspection, potentially delaying the project's approval and, consequently, the payment of the contract price. To circumvent this, they conspired with a subcontractor to create a set of forged "disposal slips" falsely showing that 525 cubic meters of sludge had been properly and legally processed.

They submitted these forged slips to the Osaka government official in charge of the inspection. Deceived by the fraudulent paperwork, the inspector passed the project. Based on this approval, the prefectural government processed the payment, and the full contract price of 72.88 million yen was transferred to the company's bank account.

The Journey Through the Courts: Two Flawed Theories of Harm

The defendants were charged with and convicted of fraud, but the lower courts struggled to define the exact nature of the financial harm suffered by the government.

- The High Court's Theory (Direct Financial Loss): The appellate court argued that the government did suffer a direct financial loss. It reasoned that the illegal dumping of sludge constituted a form of non-performance under the contract, and that the contract price should have been reduced accordingly. Therefore, by receiving the full amount, the company had defrauded the government of the amount that should have been deducted.

- The Trial Court's Theory (Harm by Early Payment): The initial trial court took a different approach. It found that because it was a lump-sum contract, the government was not actually entitled to a price reduction based on the volume of sludge disposed. The company was owed the full 72.88 million yen for the completed piling work. However, the court reasoned that the deception had caused the payment to be made earlier than it would have been if the truth were known, as an investigation into the sludge discrepancy would have delayed the inspection approval. It concluded that this "undue acceleration" of payment was a sufficient financial harm to constitute fraud.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: A New Test for "Damage by Acceleration"

The Supreme Court rejected both of the lower courts' theories but found the trial court's "payment acceleration" idea to be a more plausible starting point. First, the Supreme Court dismissed the High Court's reasoning, finding that under the terms of the lump-sum contract, the government had no civil law right to demand a price reduction based on the sludge disposal methods. The illegal dumping was a violation of public environmental law, but it did not breach the construction contract in a way that affected the final price.

The Court then turned to the more nuanced "payment acceleration" theory. It acknowledged that, in principle, using deception to get paid what you are owed, but sooner than you should, can be fraud. However, it established a new, high bar for when such an act becomes a crime.

The Court announced its landmark test:

"...in order for the crime of fraud to be established on the grounds that one has unduly received payment of a contract price to which one is originally entitled at an early date, it is necessary that the payment date was advanced for a period of time sufficient for it to be said to be a different payment in the eyes of generally accepted social standards."

The underlying logic of this test is that the only "damage" the victim (the payer) suffers in such a case is the loss of the use of their money for the period it was paid out early—essentially, the lost interest they could have earned. The Supreme Court's test asks whether this period of acceleration is so significant that the loss becomes more than trivial. A delay of a few days might not meet this standard, but an acceleration of many months or years might be considered a "different payment" altogether and thus a significant, punishable harm.

Because the lower courts had failed to make a factual finding as to how long the payment was actually accelerated by the deception, the Supreme Court found the conviction for fraud to be unsupported. It overturned the judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings to determine if the delay would have been significant enough to meet this new standard.

Analysis: A Specific Rule, Not a General Principle

This 2001 Supreme Court decision is a crucial piece of jurisprudence because it carves out a very specific rule for a narrow, but important, set of circumstances. Legal commentary on the case warns against over-generalizing its meaning. This ruling does not mean that a "substantive financial loss" is now required for all fraud convictions in Japan. The long-standing principle that fraud can be established even when a victim receives an item of "equivalent value" (as in the 1959 "miracle massager" case) remains good law. Those cases operate on a different principle: that the transaction itself was unwanted and induced by lies about its fundamental nature.

The "payment acceleration" test is a distinct rule designed specifically for the scenario where a perpetrator fraudulently obtains the correct amount of money to which they are legally entitled, but simply receives it sooner than they should have.

Conclusion: Defining Damage with Precision

The 2001 Supreme Court decision provides a highly specific and nuanced rule for a difficult gray area of fraud law. It establishes that while getting paid what you are owed is not a crime, using lies to get paid early can be, but only under specific conditions. The acceleration of the payment must be so significant that it constitutes a real and tangible financial harm to the payer, transforming it into what society would consider a "different payment."

The ruling is a prime example of the judiciary's effort to bring precision to the legal concept of "property damage." It ensures that the powerful charge of fraud is reserved for cases involving legally significant harm, preventing the criminal law from being used to punish what may amount to minor procedural shortcuts or trivial financial advantages.