Franchising in Japan: Antimonopoly Act Risks, ASBP Case Study & Compliance Steps for US Brands

TL;DR

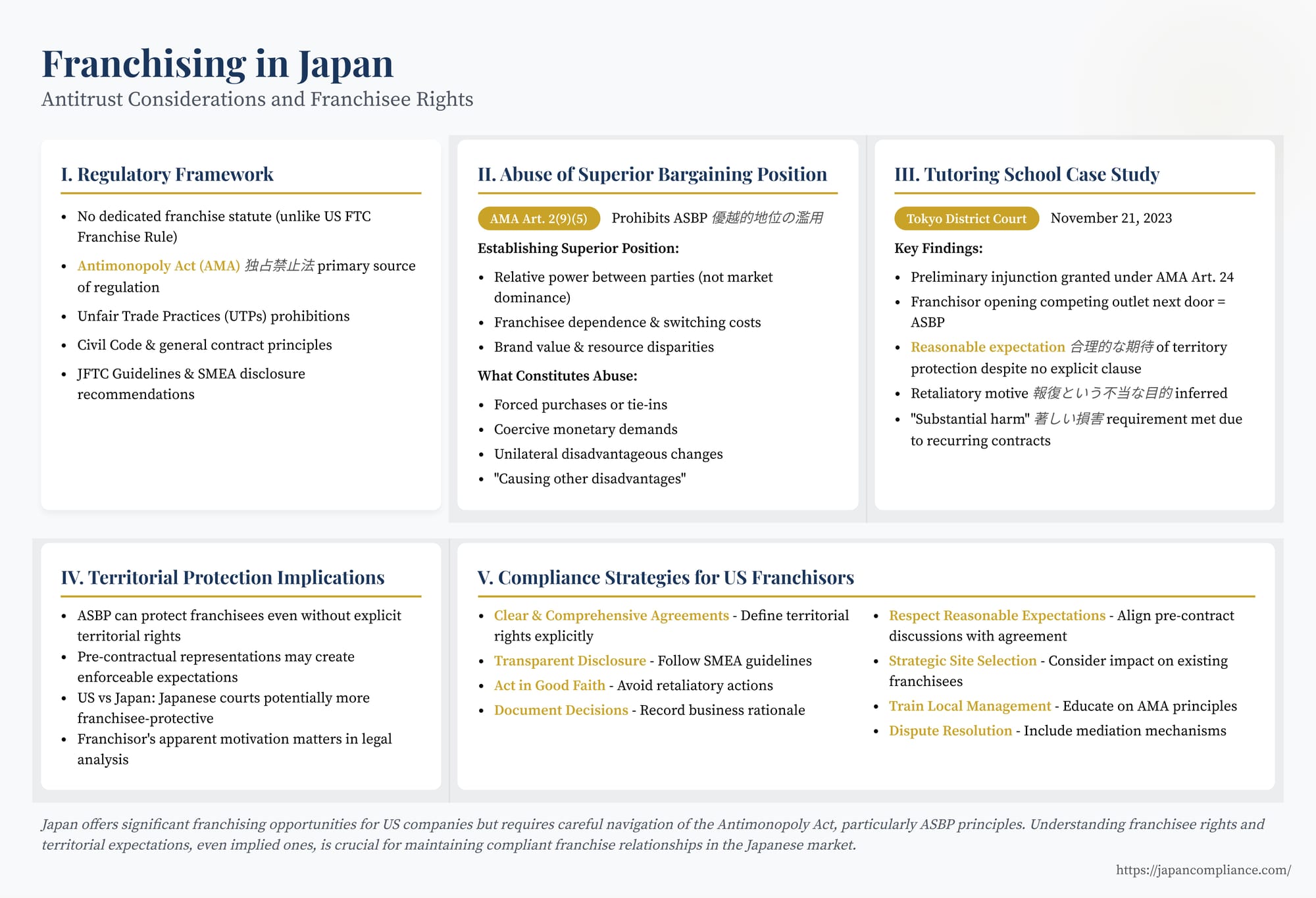

- Japan lacks a single franchise statute, so antitrust rules—especially the Antimonopoly Act’s Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP)—govern fairness.

- A 2023 Tokyo District Court injunction shows franchisors may not undermine franchisees’ “reasonable territorial expectations,” even if not in the contract.

- US franchisors must draft clear territory clauses, disclose site-selection policies, and avoid retaliatory conduct to stay AMA-compliant.

Table of Contents

- The Regulatory Framework: Beyond a Single Franchise Law

- The Antimonopoly Act and Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP)

- The Tutoring School Injunction: A Case Study in ASBP

- Implications for Dominant Outlets and Territorial Protection

- Injunctive Relief under AMA Article 24

- Comparison with US Approaches

- Compliance Strategies for US Franchisors in Japan

- Conclusion

Franchising offers a compelling pathway for US businesses to expand into the lucrative Japanese market, leveraging local expertise while maintaining brand consistency. However, navigating the legal landscape requires understanding regulations distinct from those in the United States. While Japan lacks a dedicated federal-level franchise statute akin to the US FTC Franchise Rule, its Antimonopoly Act (AMA - 独占禁止法, dokusen kinshi hō) plays a crucial role, particularly through its prohibitions on Unfair Trade Practices (UTPs), including the potent concept of Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP - 優越的地位の濫用, yūetsuteki chii no ran'yō).

A recent Tokyo District Court decision granting a preliminary injunction to a tutoring school franchisee highlights the practical application and significance of these AMA principles, especially concerning territorial expectations and franchisor conduct. This article explores key antitrust considerations for US franchisors in Japan, using this case as a practical illustration.

The Regulatory Framework: Beyond a Single Franchise Law

Unlike the US, Japan does not have a specific, comprehensive law governing franchise relationships. Instead, the legal framework is built upon several pillars:

- Antimonopoly Act (AMA): This is the primary legislation addressing competition issues, including fairness in vertical relationships like franchising. Its provisions against Unfair Trade Practices, especially ASBP, are highly relevant.

- Contract Law: The specific terms of the franchise agreement are, of course, fundamental, governed by Japan's Civil Code and general contract principles.

- Guidelines: While not law, guidelines issued by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) on vertical restraints and franchising, and by the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency (SMEA) on franchise disclosure, provide important interpretations and best practice recommendations.

The Antimonopoly Act and Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP)

The AMA prohibits various Unfair Trade Practices (不公正な取引方法 - fukōsei na torihiki hōhō). Among these, Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP) is particularly pertinent to franchising. ASBP occurs when a party with a superior bargaining position relative to another party in a continuous transaction uses that position to impose unjust disadvantages on the other party in light of normal commercial practices (AMA Article 2, Paragraph 9, Item 5).

1. Establishing Superior Bargaining Position (SBP):

SBP is not about absolute market dominance but rather the relative bargaining power between the two parties. It's determined case-by-case, considering factors like:

- The weaker party's degree of dependence on transactions with the stronger party.

- The stronger party's position in the relevant market.

- The weaker party's ability to switch to alternative business partners (switching costs).

- Disparities in size, resources, or access to information.

- The value and recognition of the franchisor's brand.

In franchising, franchisors are often found to possess SBP over their franchisees due to the franchisee's significant investment tied to the specific franchise system, reliance on the brand and know-how, and contractual restrictions (like non-compete clauses) that make switching difficult or costly. The tutoring school case affirmed this, finding SBP based on the franchisee's small size, lack of prior experience, high dependence, and the non-compete clause.

2. What Constitutes Abuse?

Once SBP is established, the focus shifts to whether the franchisor's actions constitute an "abuse" – imposing unjust disadvantages. Common examples listed in JFTC guidelines include:

- Forced purchases or tie-ins (requiring franchisees to buy unrelated goods/services).

- Coercive demands for monetary contributions, services, or information unrelated to the core transaction.

- Unilaterally disadvantageous changes to contract terms or transaction conditions.

- Unjust refusal to transact or discriminatory treatment.

- Causing other disadvantages: This is a catch-all category covering actions that unjustly harm the franchisee's interests, which was central to the tutoring school case.

The key is whether the disadvantage imposed is "unjust in light of normal commercial practices."

The Tutoring School Injunction: A Case Study in ASBP

The Tokyo District Court's decision on November 21, 2023, provides valuable insights into how ASBP principles, particularly the "causing disadvantage" aspect, apply in franchise disputes.

Case Background:

A franchisee (X) of a tutoring school system operated by franchisor (Y) sued Y over disputes concerning mandatory advertising fee collections. Shortly after X filed the lawsuit, Y, through a wholly-owned subsidiary, leased premises directly adjacent to X's school (in the same building X had previously occupied) and announced plans to open a competing company-owned school. Franchisee X sought a preliminary injunction under AMA Article 24 (and alternatively, the franchise agreement) to prevent the opening of the competing school, arguing it constituted ASBP or a breach of contract.

The Court's Findings (Preliminary Injunction Stage):

The court granted the injunction, finding preliminary evidence supporting X's claims:

- SBP Confirmed: As mentioned, the court found Y held SBP over X.

- ASBP - Causing Disadvantage: The court determined that opening the competing outlet constituted an abuse by causing unjust disadvantage through several lenses:

- Undermining Reasonable Expectations of Territory: Critically, the court acknowledged that while the franchise agreement did not explicitly grant exclusive territorial rights, the structure of Y's franchise system and explanations given by Y's advisor before the contract was signed had created a "reasonable expectation" (合理的な期待 - gōriteki na kitai) for X regarding a certain degree of territorial protection. Opening a directly competing outlet in such close proximity severely harmed this reasonable expectation, constituting an unjust disadvantage. This is significant because it suggests that even without explicit contractual guarantees, franchisors may have a duty under the AMA not to undermine territories reasonably expected by franchisees based on pre-contractual representations or the overall system design.

- Retaliatory Motive: The court inferred that Y's decision to open the competing school was likely motivated by retaliation ("報復という不当な目的" - hōfuku to iu futō na mokuteki) against X for filing the initial lawsuit regarding advertising fees. Such a motive was deemed improper and contributed to the finding of abuse.

- Violation of Normal Commercial Practices: The combination of undermining reasonable expectations and the apparent retaliatory motive led the court to conclude that Y's action was "unjust in light of normal commercial practices" (正常な商慣習に照らして不当に - seijō na shōkanshū ni terashite futō ni).

Implications for Dominant Outlets and Territorial Protection

This case carries significant implications for how territorial disputes and franchisor "encroachment" (opening competing outlets near existing franchisees) might be handled under Japanese law.

While explicit contractual territory clauses provide the clearest protection, the tutoring school decision suggests that the ASBP framework can offer a degree of protection even in their absence. If a franchisor's actions or representations lead a franchisee to form a reasonable expectation of some territorial buffer, the franchisor subsequently undermining that expectation—especially with potentially improper motives—can be deemed an abuse of its superior position.

This aligns with JFTC guidelines that often emphasize the importance of franchisors providing clear disclosure about their policies regarding the opening of nearby company-owned or other franchised outlets ("dominant outlets"). Failure to disclose such policies accurately, or acting contrary to reasonable expectations created, strengthens a franchisee's potential ASBP claim. US franchisors should be mindful of not just the letter of their contracts but also the expectations they might create through their system design, marketing materials, and pre-contractual discussions in Japan.

Injunctive Relief under AMA Article 24

The case is also notable for its successful use (at the preliminary stage) of AMA Article 24. This provision allows private parties (like franchisees) who suffer or are likely to suffer "substantial harm" (著しい損害 - ichijirushii songai) due to an Unfair Trade Practice (like ASBP) to directly petition the court for an injunction to stop the offending conduct.

- Rarity: As the commentary in the source PDF notes, successful injunctions under Article 24, whether preliminary or final, have been rare in Japan. This decision, therefore, marks a potentially significant development in private AMA enforcement.

- "Substantial Harm" Requirement: A key hurdle for Article 24 injunctions is proving "substantial harm." The court in the tutoring case found this requirement met, reasoning that the direct competition would significantly damage the franchisee's revenue. Crucially, it noted that because tutoring contracts are often annual or multi-year, the negative impact wouldn't be fleeting but would likely persist for years ("年単位で続く").

- Broader Applicability?: The commentary rightly questions whether this finding on substantial harm, tied to the specific long-term contract nature of the tutoring industry, can be easily generalized. In industries with more transactional customer relationships (e.g., retail, food service), demonstrating that competition from a nearby outlet causes harm that is both "substantial" and likely long-lasting enough to warrant an injunction might be more challenging. The lack of clear judicial standards for what constitutes "substantial harm" remains a point of uncertainty.

Comparison with US Approaches

The Japanese approach, particularly the focus on ASBP, differs from typical US franchise dispute resolution:

- ASBP vs. US Law: The US lacks a direct federal equivalent to ASBP. While franchisors hold significant bargaining power, disputes are often handled under:

- Specific contract breaches.

- State franchise relationship laws (if applicable, governing termination, non-renewal, etc.).

- General contract principles (like the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing, though its application varies greatly by state).

- Antitrust laws (like Sherman Act Section 1 for tying arrangements), but these typically require proving market power in a relevant market and anti-competitive effects, often a higher bar than establishing relative SBP.

- Territorial Disputes: In the US, encroachment disputes usually hinge heavily on the explicit language of the franchise agreement regarding territory. While good faith arguments can be made, courts are often reluctant to imply territorial rights where none are granted contractually. The Japanese court's willingness to consider "reasonable expectations" under ASBP appears potentially more franchisee-protective in this specific regard.

- Disclosure: The US relies heavily on pre-sale disclosure mandated by the FTC Franchise Rule to ensure franchisees are informed about the system, including potential competition from the franchisor. Japan relies more on SMEA guidelines and general principles of fair dealing.

Compliance Strategies for US Franchisors in Japan

To mitigate risks related to the AMA and ASBP when franchising in Japan, US franchisors should consider the following:

- Clear and Comprehensive Agreements: Define rights and obligations clearly, especially regarding territory (granting exclusivity, rights of first refusal, or explicitly reserving the franchisor's right to compete), fees, and operational requirements. Ensure consistency between the agreement and pre-contractual representations.

- Transparent Disclosure: While not mandated by a specific franchise law, align disclosure practices with SMEA guidelines and international best practices. Be upfront about policies regarding company-owned stores or multi-unit franchising in proximity to existing units.

- Act in Good Faith: Avoid using superior bargaining power to impose terms or take actions that are commercially unreasonable or retaliatory. Document legitimate business reasons for decisions that might negatively impact franchisees.

- Respect Reasonable Expectations: Be mindful of the expectations created by the franchise system's design, marketing, and communications. Avoid misleading potential franchisees about territorial protection or operational support.

- Strategic Site Selection: Carefully consider the potential impact on existing franchisees when placing new company-owned or franchised outlets. Document the rationale for site selection.

- Training for Local Management: Ensure that managers and staff interacting with Japanese franchisees understand the principles of the AMA, particularly ASBP, and the importance of fair dealing.

- Dispute Resolution: Consider including fair and accessible dispute resolution mechanisms (like mediation) in the franchise agreement.

Conclusion

Japan offers significant opportunities for US franchisors, but success requires careful attention to its unique legal environment. The Antimonopoly Act, and specifically the prohibition on Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position, provides a powerful tool for franchisees facing unfair treatment. The recent tutoring school injunction case serves as a potent reminder that franchisors must act fairly, respect reasonable expectations (even if not explicitly codified in the contract), and avoid retaliatory conduct. For US companies entering or operating in the Japanese franchise market, a proactive approach incorporating clear agreements, transparent communication, fair practices, and a solid understanding of ASBP principles is essential for building sustainable and compliant franchise relationships.

- False IP Takedowns on Japanese E-Commerce Platforms: UCPA Liability & Risk-Control Guide

- Antitrust Enforcement in Japan’s Energy Sector: JFTC Lessons from Cartel & Collusion Cases

- Director Liability and Corporate Donations in Japan: Balancing Philanthropy and Fiduciary Duty

- JFTC Guidelines Concerning Franchise Systems (PDF)

- SMEA Franchise Disclosure Guidance (Japanese)