Foundations of International Jurisdiction in Japan: The Malaysian Airline System Landmark Case

Date of Judgment: October 16, 1981

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

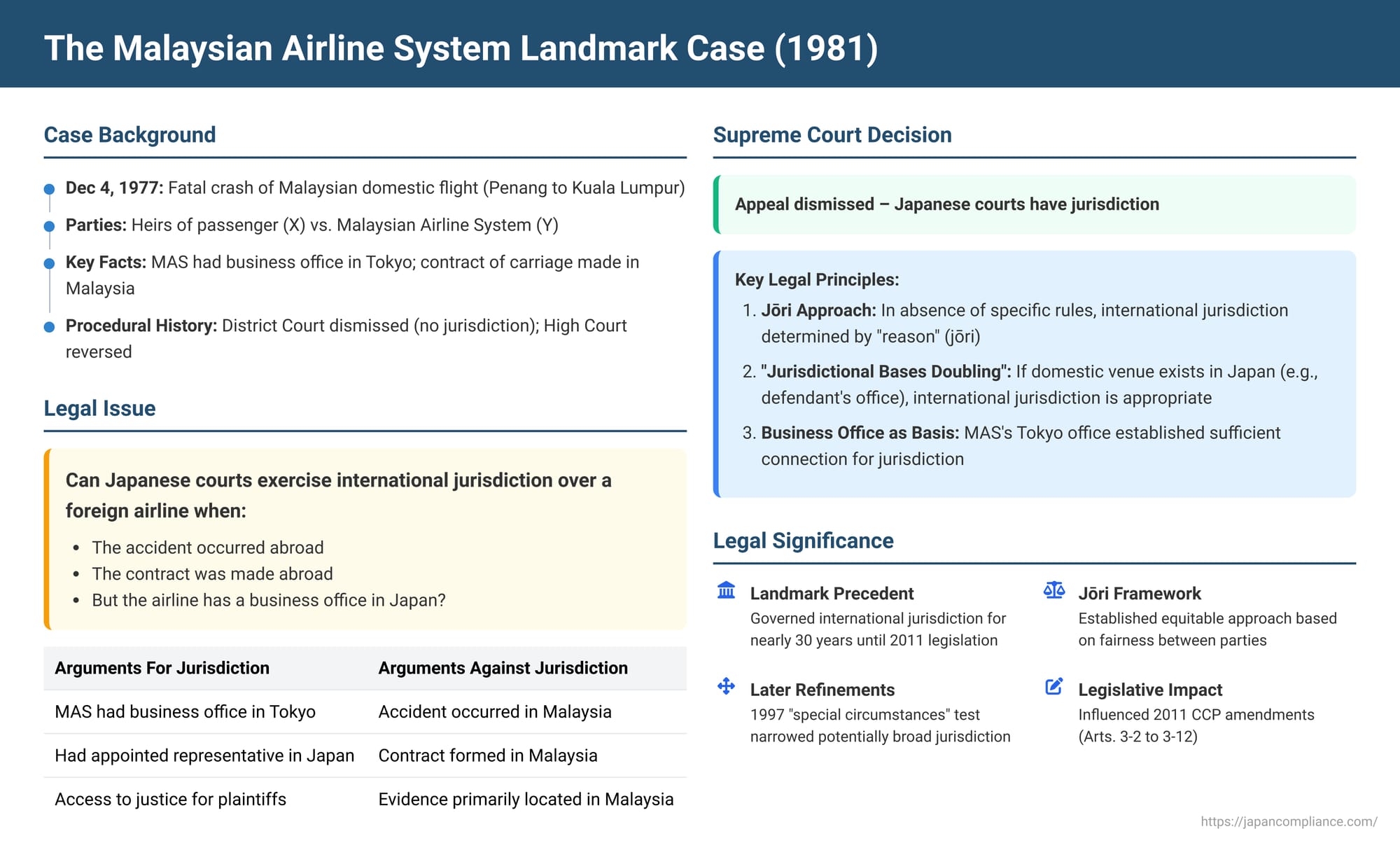

Before Japan comprehensively codified its rules on international adjudicatory jurisdiction in its Code of Civil Procedure in 2011, the principles governing when Japanese courts could hear cases involving foreign parties or foreign elements were largely developed through case law. A pivotal decision in this evolution was the Supreme Court's ruling on October 16, 1981, in a case against Malaysian Airline System Berhad. This judgment became a leading authority for decades, shaping the approach to asserting jurisdiction over foreign corporations in Japan.

The Factual Background: An Air Crash in Malaysia, A Lawsuit in Japan

The case arose from a tragic accident:

- Mr. A, a passenger, died when a flight operated by Y (Malaysian Airline System Berhad, "MAS") crashed in Malaysia on December 4, 1977. The flight was a domestic Malaysian route between Penang and Kuala Lumpur, and the contract of carriage had been concluded in Malaysia.

- MAS was a foreign corporation established under Malaysian law, with its head office in Malaysia. However, it maintained a business office (営業所 - eigyōsho) in Tokyo, Japan, and had appointed a representative in Japan.

- The heirs of Mr. A (X et al.) filed a lawsuit in the Nagoya District Court in Japan against MAS, seeking damages for breach of the contract of carriage.

The Legal Question: Could Japanese Courts Hear the Case Against the Foreign Airline?

The Nagoya District Court initially dismissed the suit, finding a lack of international adjudicatory jurisdiction in Japan. It reasoned that the core elements of the dispute (contract formation, performance, accident location) were all in Malaysia, and considerations of evidence and convenience favored Malaysian courts.

However, the Nagoya High Court reversed this decision. It found that because MAS had a business office in Tokyo, this could establish a general forum in Japan. The High Court deemed it "naturally reasonable" (条理上当然 - jōri jō tōzen) for Japan to exercise jurisdiction and remanded the case. MAS appealed this finding of jurisdiction to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Affirming Jurisdiction Based on "Reason" (Jōri)

The Supreme Court dismissed MAS's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that Japanese courts had jurisdiction. The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- General Principle and Exceptions: The Court acknowledged the general principle that a state's adjudicatory power, as an aspect of its sovereignty, is generally coextensive with its sovereign territory. Therefore, as a rule, Japanese courts would not have jurisdiction over a foreign corporation with its head office abroad unless that corporation voluntarily submitted to it. However, the Court also recognized that exceptions to this principle were necessary. Specifically, for cases concerning land within Japan or other matters where a defendant has some "legal connection" with Japan, it might be appropriate to subject that defendant to Japanese jurisdiction, regardless of their nationality or physical location.

- Determining Jurisdiction by "Reason" (Jōri) in the Absence of Specific Rules: The Court noted that, at the time, Japan had no direct statutory provisions, applicable treaties, or clearly established principles of international law governing international adjudicatory jurisdiction. In such a situation, the Court held that the scope of jurisdiction should be determined based on "jōri" (reason, natural justice, or equity). This determination should be guided by the ideals of ensuring fairness between the parties and the proper and prompt administration of justice.

- The "Jurisdictional Bases Doubling" Approach: The Supreme Court then articulated a practical method for applying jōri:

If any of the grounds for domestic territorial jurisdiction (venue rules) under Japan's Code of Civil Procedure were found to exist within Japan, it would be consistent with jōri to subject the defendant to Japan's international adjudicatory power for lawsuits related to those grounds. The Court listed examples of such domestic venue rules: the defendant's residence, the location of a corporation's office or business office (old Code of Civil Procedure Article 4), the place of performance of an obligation, the location of the defendant's property, or the place where a tort occurred. - Application to Malaysian Airline System: The Supreme Court found that MAS, despite being a foreign corporation with its head office in Malaysia, had appointed a representative in Japan and maintained a business office in Tokyo. Applying its "jurisdictional bases doubling" principle, the presence of this business office in Japan (a ground for domestic general venue for corporations under the old Code of Civil Procedure Article 4) was sufficient to make it "appropriate to subject Y (MAS) to Japan's adjudicatory power."

Therefore, the High Court's finding of jurisdiction was affirmed.

Historical Significance and Impact

The 1981 Malaysian Airline System judgment was a landmark decision that served as the primary authority on international adjudicatory jurisdiction in Japan for nearly three decades, until specific legislative provisions were introduced into the Code of Civil Procedure in 2011.

- Establishing a General Framework: It provided a general, albeit broad, framework for Japanese courts to determine when they could hear cases against foreign defendants by looking to domestic venue rules as a guide for what "reason" (jōri) dictated.

- Criticisms and Subsequent Refinements: This "doubling" approach, while offering a degree of predictability, also drew criticism. Scholars pointed out that it could potentially lead to "exorbitant jurisdiction"—that is, Japanese courts asserting jurisdiction in situations where Japan's connection to the dispute was minimal or where it might be unfair to the foreign defendant. For example, the mere presence of any business office, regardless of its connection to the lawsuit's subject matter, could theoretically establish general jurisdiction over a foreign company for any type of claim.

A later Supreme Court case in 1997 (often referred to as the Goto v. Malaysian Airline System case) introduced a significant limitation. It held that even if a domestic venue ground (in that case, the place of performance of an obligation) technically existed in Japan, international jurisdiction could still be denied if "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) made its assertion unreasonable. This 1997 ruling effectively refined and constrained the potentially overbroad implications of the 1981 decision. - Stimulus for Legal Development: The 1981 Malaysian Airline System case, along with the subsequent debates and refinements, played a crucial role in stimulating academic discussion and legal scholarship on international civil procedure in Japan. This intellectual groundwork was instrumental in paving the way for the 2011 amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure, which comprehensively codified rules for international adjudicatory jurisdiction.

Relevance in Light of Current Law (Post-2011 CCP Amendments)

Today, international jurisdiction in Japan is governed by specific provisions in the Code of Civil Procedure (Articles 3-2 to 3-12). Under these current rules:

- General Jurisdiction (Art. 3-2): General jurisdiction over a foreign corporation is typically found if its "principal office or business office is in Japan." The mere presence of a branch or secondary business office, like the MAS Tokyo office in this case, would generally not suffice for general jurisdiction if the principal office is abroad.

- Special Jurisdiction (Art. 3-3): The current law provides various grounds for special jurisdiction based on connections to Japan (e.g., place of tort, place of performance of a contract if related to the Japanese office's business, location of assets). For a case like the 1981 MAS dispute, where the contract was made and performed in Malaysia and the accident occurred there, establishing special jurisdiction under the current rules based solely on the Tokyo office for an unrelated claim might be difficult.

From the perspective of the current, more nuanced statutory framework, the 1981 Malaysian Airline System ruling might be seen as having endorsed a relatively broad basis for jurisdiction. However, its emphasis on "reason" and "fairness," and its attempt to find a practical solution in the absence of legislation, were foundational.

Conclusion

The 1981 Malaysian Airline System Supreme Court decision remains a historically significant judgment in the development of Japanese international civil procedure. It established a crucial, albeit subsequently refined, principle for asserting jurisdiction over foreign corporations by looking to domestic venue rules as an indicator of what "reason" and fairness demanded. While its specific jurisdictional test has now been largely superseded by detailed legislative provisions, the case was instrumental in shaping Japan's approach to cross-border litigation for many years and highlighted the enduring challenge of balancing the effective administration of justice with the principles of international comity and fairness to all parties involved.