Former Bankruptcy Trustee's Standing Post-Proceedings: A 1993 Japanese Supreme Court Decision

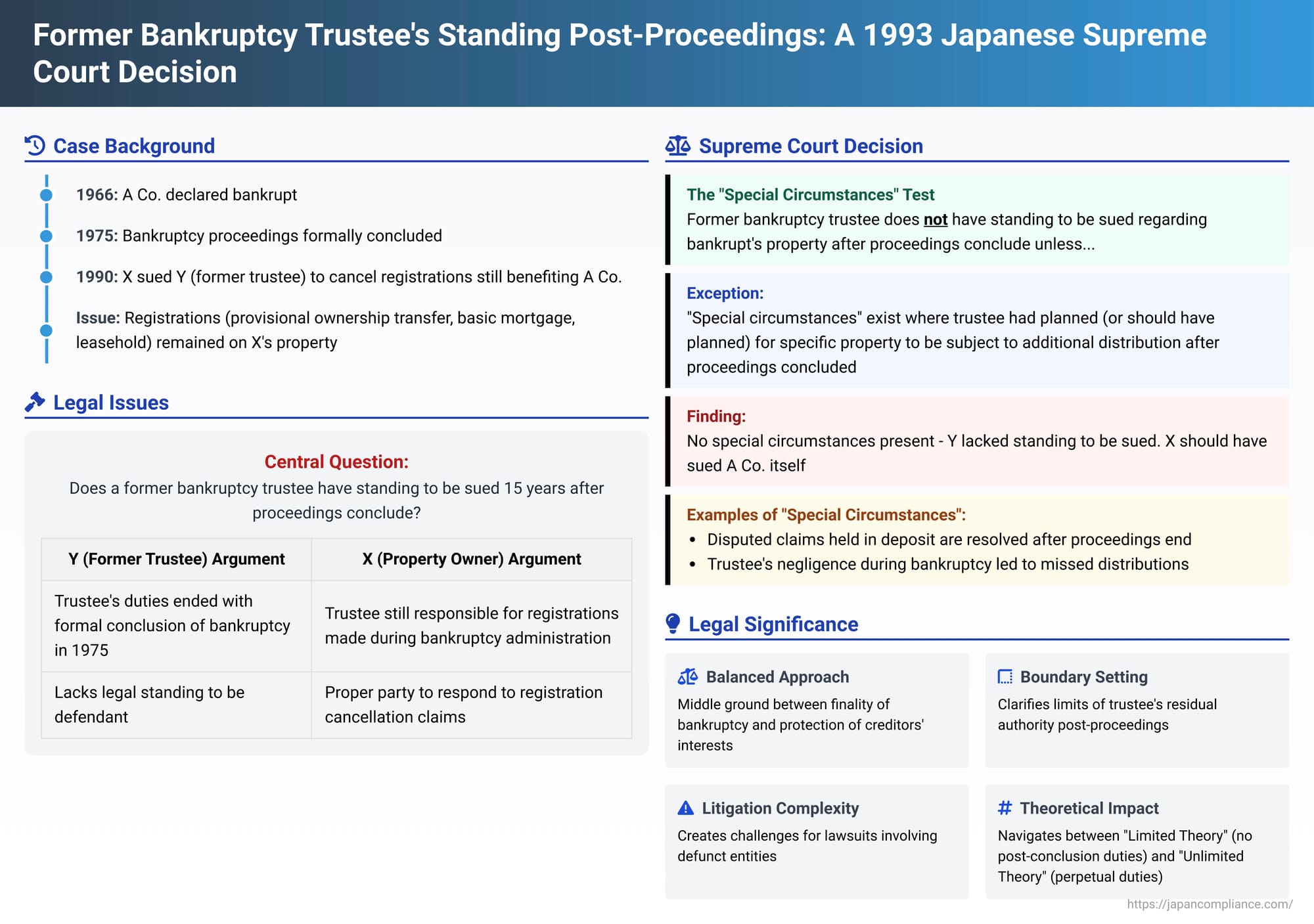

On June 25, 1993, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning the legal standing of a former bankruptcy trustee to be sued in relation to the bankrupt company's property matters long after the formal conclusion of bankruptcy proceedings. The Court established a "special circumstances" test to determine if a former trustee retains any residual authority and thus, standing as a party in such litigation.

Factual Background: Lingering Registrations and a Belated Lawsuit

The case involved A Co., which had been declared bankrupt on October 13, 1966, under Japan's old Bankruptcy Act. The bankruptcy proceedings for A Co. were formally concluded with a court order on December 25, 1975. Despite this conclusion, several registrations benefiting A Co. remained on certain real property owned by X. These included a provisional registration of a right to claim ownership transfer, a registered basic mortgage (neteitōken), and a provisional registration of a leasehold right subject to a condition precedent.

Approximately 15 years after the bankruptcy proceedings had ended, on October 30, 1990, X initiated a lawsuit. X sued Y, who had served as the bankruptcy trustee for A Co., seeking the cancellation of these long-standing registrations. X argued that there was no valid underlying claim justifying these encumbrances.

In defense, Y, the former trustee, argued that they lacked legal standing to be a defendant. Y contended that with the formal conclusion of the bankruptcy proceedings, the trustee's duties and powers had also terminated. The court of first instance, however, found that Y did have standing and ruled in favor of X, ordering the cancellation of the registrations. Y's appeal to the High Court was dismissed. Consequently, Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Quandary: Trustee's Role After Bankruptcy Proceedings End

Generally, the appointment of a bankruptcy trustee grants them the authority to manage and dispose of the bankrupt's assets (the bankruptcy estate) for the benefit of creditors. This role, including the standing to sue or be sued in relation to estate matters, typically ceases when the bankruptcy proceedings are formally concluded by a court order (hasan shūketsu kettei). Upon conclusion, the bankrupt entity usually regains the power to manage and dispose of any property that was not administered or distributed during the bankruptcy.

However, the Bankruptcy Act (both the old version applicable to this case and the current one) provides for the possibility of an "additional distribution" (追加配当 - tsuika haitō). If, after the final distribution has been made (or notice thereof given), substantial property becomes newly available for distribution to creditors, the trustee is obligated to make such an additional distribution, even if the main proceedings have formally concluded. This provision implies that a trustee's duties and powers might not entirely vanish upon the formal closure, at least for the purpose of these supplementary distributions.

The central question in this case was the extent of these residual duties and powers. Specifically, could a former trustee, many years after the bankruptcy's conclusion, still be the proper party to be sued concerning registrations that related to potential assets of the former bankrupt company? This hinges on whether the former trustee retains any relevant management and disposal authority.

The Supreme Court's "Special Circumstances" Test for Trustee Standing

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts' decisions and dismissed X's lawsuit against Y, the former trustee, finding that Y indeed lacked standing.

The Court laid down the following rule: In a lawsuit concerning property of a bankrupt entity that arises after the bankruptcy proceedings have concluded—even if that property could have potentially formed part of the bankruptcy estate—the former bankruptcy trustee does not have legal standing to be a party (either as plaintiff or defendant) UNLESS "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō) exist. Such special circumstances would be present if the trustee, during the course of the original bankruptcy proceedings, had planned, or reasonably should have planned, for that specific property to be the subject of an additional distribution after the formal conclusion of the proceedings. (This was with reference to Article 283, paragraph 1, latter part, of the old Bankruptcy Act, now Article 215, paragraph 1, of the current Act).

The Court's reasoning included these points:

- General Cessation of Powers: As a general rule, when bankruptcy proceedings conclude, the trustee's authority to manage and dispose of the bankrupt's property is extinguished. The bankrupt (if still existing) reacquires these powers.

- Exception for Continuing Duties: However, if such "special circumstances" are present, it signifies that the trustee's duties have not yet fully concluded. In such cases, their management and disposal authority over the specific property relevant to the additional distribution would also continue. The Court provided examples of "special circumstances":

- If, after the proceedings conclude, funds held in deposit for a creditor (whose claim was disputed) become available for distribution to other creditors because the first creditor ultimately lost their claim determination lawsuit.

- If the trustee was negligent in performing their duties during the bankruptcy proceedings and, as a result, failed to make distributions that should have been made.

- No Special Circumstances Here: Applying this to the facts, the Supreme Court found no indication that Y, during A Co.'s bankruptcy proceedings which ended in 1975, had planned, or should have planned, for any potential claim secured by "these registrations" to be part of an additional distribution. Therefore, Y's duties and powers regarding such assets had ceased, and Y lacked the legal standing to be sued. The Court suggested that X should have directed the lawsuit against A Co. itself (or its appropriate representative, given it was a company whose bankruptcy had concluded).

Navigating the Scope of Additional Distributions and Trustee Duties

The Supreme Court's "special circumstances" test provides a more nuanced approach than some of the pre-existing legal theories regarding additional distributions:

- The "Limited Theory" (prevailing view): This theory generally restricts additional distributions to assets that were discovered or became available before the formal conclusion of the main bankruptcy proceedings. The rationale is to prevent bankruptcy proceedings from dragging on indefinitely, which would undermine legal stability.

- The "Unlimited Theory": This opposing view argues that as long as any property belonging to the statutory bankruptcy estate remains, the trustee’s duty to distribute it should continue, even if discovered long after the formal closure, to ensure fairness to creditors.

The Supreme Court, by introducing the "special circumstances" criterion, did not rigidly adhere to the "limited theory." While it acknowledged that the trustee's role is not open-ended, its test allows for the possibility that even assets "discovered" or dealt with after the formal conclusion could fall under a trustee's residual duties if, for instance, the trustee's prior negligence prevented their earlier administration, or if plans for their later distribution were, or should have been, in place. This flexible approach can address situations where assets might have been concealed by the bankrupt or overlooked due to a trustee's oversight, thereby offering a potential corrective to the strictness of the "limited theory."

Implications of Denying Trustee Standing

If a former bankruptcy trustee lacks standing to be sued, the question arises as to who the proper defendant should be. The Supreme Court indicated that the bankrupt entity itself (A Co. in this instance) would be the correct party. However, this can lead to further complexities, especially if the bankrupt entity was a corporation that may have been dissolved or lacks active representation many years after its bankruptcy has concluded. Determining the appropriate representative or liquidator for such a defunct entity can be a challenge in itself.

While the "special circumstances" test allows for flexibility, its inherent lack of precise definition can also create uncertainty for litigants, who risk having their cases dismissed if they incorrectly assess whether such circumstances apply and thus sue the wrong party.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1993 decision in this case provides important guidance on the boundaries of a former bankruptcy trustee's legal role and standing after the formal termination of bankruptcy proceedings. It confirms that while a trustee's duties are generally concluded, they are not absolutely extinguished if "special circumstances" demonstrate a continuing need for the trustee to administer certain assets, particularly for an additional distribution to creditors. This ruling attempts to strike a balance between the need for finality in bankruptcy proceedings and the imperative of ensuring that creditors receive what they are duly owed, even if it requires a limited extension of the trustee's responsibilities under specific, justifiable conditions. The judgment highlights that the path to resolving issues related to a bankrupt's property, many years after the main proceedings have closed, requires careful consideration of who holds the residual legal authority.