Formal Auctions in Japan: Supreme Court Confirms "No Surplus" Rules Apply to Co-Owned Property Partition Sales

Date of Supreme Court Decision: February 7, 2012

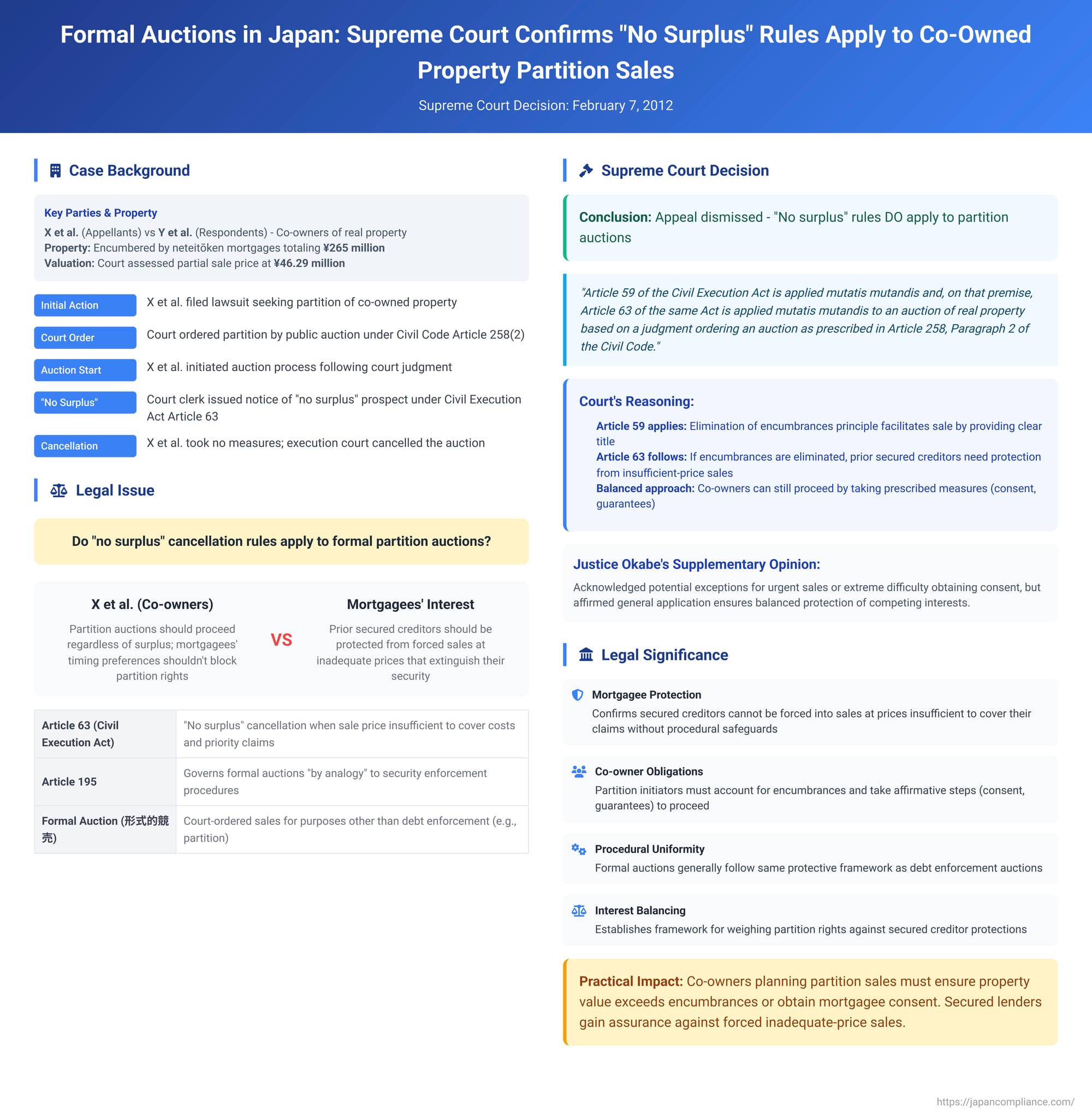

In Japan, real property auctions are not solely for enforcing debts. A distinct category, known as "formal auctions" (形式的競売 - keishiki-teki keibai), serves various other legal purposes, such as the court-ordered sale of co-owned property to facilitate its partition among owners. A key question that arose was whether standard rules from debt enforcement auctions, particularly the "no surplus" provision (which can cancel an auction if proceeds are insufficient to cover prior secured debts and costs), apply to these formal partition auctions. On February 7, 2012, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan (Heisei 23 (Kyo) No. 31) provided a significant affirmation on this issue.

The Background: A Co-Ownership Dispute and Court-Ordered Sale

The case involved X et al. (appellants) and Y et al. (respondents), who were co-owners of real property. This property was encumbered by neteitōken (revolving mortgages) in favor of financial institutions, with a total maximum secured amount of ¥265 million.

X et al. filed a lawsuit against Y et al. seeking the partition of their co-owned property. The court, in its final judgment, ordered that the property be sold by public auction, and the net proceeds (after deducting auction expenses) be divided among the co-owners according to their respective shares. This method of partition, by converting the property into money for division, is provided for under Article 258, Paragraph 2 of the Japanese Civil Code.

Following this judgment, X et al. initiated the auction process. However, a complication arose when the execution court determined the standard sales price for a part of the property to be ¥46.29 million. (The reference to a "partial sale" in the facts is somewhat ambiguous in the context of a full partition, but it was this valuation that triggered the subsequent procedural steps.) Based on this valuation, the court clerk issued a notice to X et al., indicating that there was a prospect of "no surplus" from the sale. This notice was based on Article 63, Paragraph 1, Item (ii) of the Civil Execution Act, which addresses situations where the estimated sale price is insufficient to cover the procedural costs and the claims of creditors with rights (like mortgagees) that have priority over the auction applicant's interest.

Under Article 63, Paragraph 2, the auction initiators (X et al.) had the opportunity to avoid cancellation of the auction by taking certain measures, such as providing a guarantee to purchase the property at a price that would ensure a surplus, or obtaining the consent of the priority creditors (the mortgagees) to the sale. X et al. did not take any of these prescribed steps. Consequently, the execution court issued a decision to cancel the auction procedure.

X et al. contested this cancellation by filing an execution appeal. The appellate court (High Court) dismissed their appeal. It reasoned that Article 195 of the Civil Execution Act, which governs the procedure for formal auctions, applies Article 63 (the no-surplus rule) without reservation. The High Court further opined that it would not be appropriate to disregard the expectations of prior mortgagees concerning the timing of a sale merely because the auction was for partitioning co-owned property. Dissatisfied, X et al. obtained permission to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation

The Supreme Court, in its decision of February 7, 2012, dismissed the appeal by X et al., thereby upholding the High Court's decision.

The Court's primary holding was concise: "The High Court's determination, which assumed that Article 59 of the Civil Execution Act is applied mutatis mutandis and, on that premise, held that Article 63 of the same Act is applied mutatis mutandis to an auction of real property based on a judgment ordering an auction as prescribed in Article 258, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, can be affirmed as correct."

In essence, the Supreme Court confirmed that for a formal auction aimed at partitioning co-owned property:

- It is assumed that Article 59 of the Civil Execution Act (which deals with how existing encumbrances on the property are treated upon sale, generally adopting an "elimination principle" where such rights are extinguished and holders are paid from proceeds) applies.

- On this basis, Article 63 of the Civil Execution Act (the "no surplus" cancellation rule) also applies.

Therefore, if the anticipated proceeds from a partition auction of co-owned property are unlikely to satisfy the auction costs and the claims of pre-existing mortgagees, the auction can be cancelled unless the co-owners initiating the auction take the legally prescribed steps to avert this outcome.

Justice Okabe's Supplementary Opinion: Rationale and Potential Exceptions

Justice Kiyoko Okabe provided a supplementary opinion that, while concurring with the Court's conclusion, elaborated on the reasoning and explored potential nuances and exceptions.

1. Why Article 59 (Elimination of Encumbrances) Should Apply to Formal Auctions:

Justice Okabe argued that the "necessity of sale" is a factor in formal auctions, much like in auctions for enforcing security interests. The elimination principle, where encumbrances are generally cleared by the sale (with secured creditors receiving proceeds according to priority), facilitates the sale by providing the buyer with a clear title. This is seen as a necessary aspect of an effective public sale mechanism. While some rights are extinguished, mortgagees achieve their objective through distribution, and even junior use rights (like leases subordinate to senior mortgages) receive minimum protections under provisions like Article 395 of the Civil Code.

2. Why Article 63 (No Surplus Cancellation) Should Generally Apply to Partition Auctions:

The core of this reasoning lies in balancing the interests of the co-owners (who need to sell to partition) and the pre-existing mortgagees (who have an interest in the timing and proceeds of any sale to ensure their debt is recovered).

- If Article 63 applies: The co-owners initiating the auction have statutory avenues to prevent its cancellation if a "no surplus" situation arises. A key practical measure is obtaining the consent of the priority mortgagees (as per the proviso in Article 63, Paragraph 2). While mortgagees are not obliged to consent, negotiation is possible.

- If Article 63 does not apply: Priority mortgagees would have no effective means to block a sale that might occur at an inopportune time or at a price insufficient to cover their claims, thereby forcibly extinguishing their security without full satisfaction. Their ability to voice opinions in the preceding partition lawsuit is not a guaranteed protection, as the court is not bound by their stance when ordering an auction.

- Conclusion on Balance: Justice Okabe concluded that applying Article 63 and requiring the auction initiators (co-owners) to take steps to avoid cancellation is a more practical, effective, and balanced approach to adjusting these competing interests.

3. Potential Exceptions to Applying Article 63:

Justice Okabe also suggested that the application of Article 63 might be excluded in certain specific types of formal auctions:

- Urgent Sales: In cases like "self-help sales" (e.g., by a lienholder or pledgee to quickly dispose of perishable goods or to avoid escalating storage costs), the urgency might outweigh the interests protected by the no-surplus rule.

- High Necessity of Sale + Extreme Difficulty in Obtaining Consent: Situations where the societal or legal necessity for the sale is very high, yet the auction initiator (who might not even be the property owner) faces exceptional difficulty in contacting or obtaining consent from numerous or uncooperative priority creditors. An example given is an auction ordered under Article 59 of the Act on Building Unit Ownership, etc. (Condominium Ownership Act) to compel the sale of a unit belonging to a disruptive owner.

Justice Okabe noted that Article 195 of the Civil Execution Act, with its phrasing that formal auctions are conducted "according to the rules for... auction as a means of exercising a security interest," allows for such interpretative flexibility based on the specific purpose and nature of each type of formal auction.

Understanding "Formal Auctions" (形式的競売 - keishiki-teki keibai)

The term "formal auction" is a jurisprudential concept used to distinguish auctions not primarily aimed at satisfying a monetary debt from those conducted for compulsory execution or security enforcement. Article 195 of the Civil Execution Act specifically governs "auctions by right of retention" and "auctions for liquidation under provisions of the Civil Code, Commercial Code, or other laws." The latter category clearly falls under formal auctions. Auctions based on a right of retention are also generally understood to be formal auctions, often serving a self-help purpose to alleviate the burden of continued custody of an item. Since Article 195 merely states that these auctions follow the rules for security enforcement auctions "by analogy," many procedural details for specific types of formal auctions must be determined through interpretation, keeping their unique purposes in mind.

Scholarly Perspectives on Encumbrances in Formal Auctions

The Supreme Court's assumption that Article 59 (regarding the treatment of encumbrances) applies to partition auctions aligns with one stream of scholarly thought, but it's worth noting there has been debate:

- Some scholars have argued for an "assumption principle" (hikiuke-shugi), where the buyer in a formal auction would take the property subject to existing encumbrances. This view often stems from the idea that since formal auctions are purely for converting property to cash and may not have a built-in mechanism for distributing proceeds to secured creditors, extinguishing their rights without payment would be unjust.

- Another approach, the "mixed view" (nibun-setsu), suggested distinguishing between "liquidation-type" formal auctions (where elimination of encumbrances might be appropriate) and other types.

- The Supreme Court's stance in this case, by affirming the High Court, leans towards the "elimination principle" (shōjo-shugi) for partition auctions. This approach prioritizes facilitating the sale by offering clearer title to potential buyers. The underlying rationale is that there is no inherent injustice if secured creditors' rights are recognized through their entitlement to receive payment from the sale proceeds according to their priorities.

- However, a nuanced question remains, particularly for partition auctions conducted for the co-owners' convenience: whether even "intermediate use rights" (e.g., leases that are junior to a senior mortgage but senior to the co-owners' general interest being partitioned) should be eliminated to facilitate the sale.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's February 7, 2012, decision provides important confirmation that the "no surplus" rules outlined in Article 63 of the Civil Execution Act generally apply to formal auctions conducted for the purpose of partitioning co-owned property. This has significant implications for co-owners initiating such sales, as they must now clearly account for pre-existing mortgages and be prepared to take statutory measures to avoid auction cancellation if the property's value is insufficient to cover these prior claims. It also reassures mortgagees that their interests will be protected from forced sales at prices that disregard their secured debts. Justice Okabe’s supplementary opinion further enriches the understanding by highlighting the balancing of interests involved and suggesting a framework for considering exceptions in specific types of formal auctions where urgency or the high necessity of sale, coupled with extreme difficulty in obtaining mortgagees' consent, might warrant a different approach. This ruling reinforces the principle that while formal auctions serve purposes distinct from debt collection, they generally operate within the established procedural safeguards of Japan's civil execution framework.