Forests, Floods, and Standing to Sue: Who Can Challenge Development Permits in Japan?

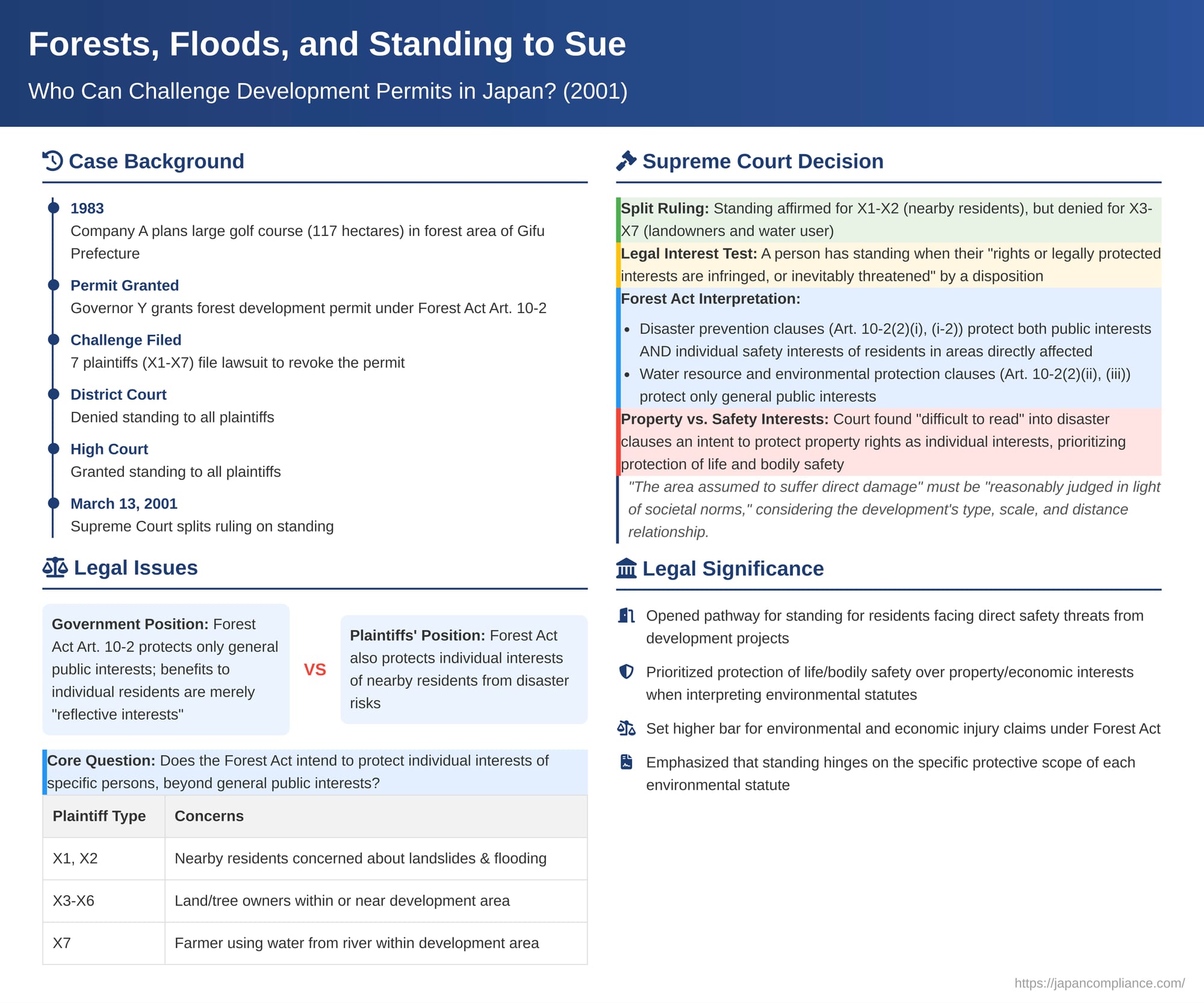

Judgment Date: March 13, 2001, Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

The development of forested land, particularly for large-scale projects like golf courses, often brings into sharp conflict the interests of developers, the economic benefits pursued by local governments, and the concerns of nearby residents and landowners regarding potential environmental damage and disaster risks. A crucial legal question in such scenarios is who has the right—or "standing"—to challenge a development permit granted by administrative authorities. A 2001 Supreme Court decision concerning a forest land development permit in Gifu Prefecture provided important, albeit nuanced, guidance on this issue, particularly regarding how different types of potential harm are weighed in determining a plaintiff's "legally protected interest."

The Forest Act's Development Permit System

Japan's Forest Act includes provisions to regulate development activities in privately-owned forests that are part of regional forest plans (excluding designated protection forests, or hoanrin, which have stricter controls). Under Article 10-2 of the Act (as it stood before a 1999 amendment), any entity planning development exceeding a certain scale must obtain a permit from the prefectural governor.

The governor is required to grant the permit if the application meets several criteria, outlined in Article 10-2, Paragraph 2. These criteria are designed to ensure that the development does not pose an undue risk of:

- Causing soil runoff, landslides, or other disasters (Item 1).

- Causing floods in areas reliant on the forest's flood prevention functions (Item 1-2).

- Causing significant hindrance to water resource availability in areas reliant on the forest's water retention functions (Item 2).

- Significantly deteriorating the environment of the surrounding area (Item 3).

Notably, while the Forest Act provides procedures for public participation (like submitting opinions or requesting public hearings) for matters such as the designation or cancellation of protection forests, it did not, at the time, have similar explicit provisions for interested parties or residents to participate in the forest land development permit process itself, beyond requiring the governor to hear the opinions of the Prefectural Forest Council and relevant municipal mayors.

The Gifu Golf Course Dispute: Facts of the Case

The case involved a plan by Company A to develop a golf course in a mountain forest area within Gifu Prefecture. Y, the Governor of Gifu Prefecture, granted Company A a forest land development permit pursuant to Article 10-2 of the Forest Act.

A group of seven individuals, X et al., challenged this permit by filing a lawsuit seeking its revocation. They argued that the permit was illegal, violating the substantive and procedural requirements of Article 10-2, Paragraph 2 of the Forest Act, and that their rights and interests would be infringed. The plaintiffs represented a range of concerns:

- X1 and X2 were residents living in the vicinity of the planned development area.

- X3, X4, X5, and X6 owned trees or land located either within or near the development area.

- X7 was a farmer who used water for agriculture from a river whose sources lay within the development area.

The Gifu District Court (First Instance) dismissed the lawsuit, denying standing to all plaintiffs. Citing the Supreme Court's 1992 Monju (No. 1) judgment (a leading case on standing in nuclear facility litigation, see Hyakusen II, No. 156), the District Court found that the provisions of Forest Act Article 10-2, Paragraph 2 were aimed at protecting general public interests. It concluded that any benefits X et al. might derive from these provisions were merely "reflective interests" (反射的利益 - hanshateki rieki) – indirect benefits accruing from general public welfare measures – rather than individually protected legal interests sufficient to grant standing.

The Nagoya High Court (Second Instance) reversed this decision. While also referencing the Monju judgment, the High Court interpreted Article 10-2, Paragraph 2 of the Forest Act more broadly. It held that these provisions, in addition to protecting general public interests, also aimed to protect the individual interests of persons within the scope of potential disaster damage – specifically their lives, bodies, property, and environmental interests. The High Court concluded that X et al. were indeed at risk of having their lives, bodies, and property infringed, or inevitably so, and therefore affirmed standing for all of them. It then remanded the case back to the District Court for a trial on the merits. Y, the Governor, appealed this High Court ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 13, 2001): A Split Ruling on Standing

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, partially overturned the High Court's decision. It affirmed standing for X1 and X2 (the nearby residents concerned about direct disaster risks) but denied standing for X3, X4, X5, X6 (land/tree owners), and X7 (the farmer concerned about water use). The case was remanded to the District Court for further proceedings concerning X1 and X2 only.

The Supreme Court's reasoning involved a careful application of its established test for standing:

I. Reaffirming the "Legally Protected Interest" Standard

The Court began by reiterating the general standard for plaintiff standing in administrative revocation lawsuits under Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA). It cited its own precedents in the Monju (No. 1) case and the 1997 Kawasaki City Land Development case, stating that a "person who has legal interest" to seek revocation is "one whose rights or legally protected interests are infringed, or are inevitably threatened with infringement, by the said disposition." The Court further explained that if the administrative statute governing the disposition (here, the Forest Act) "is construed as including an aim to protect, as individual interests of each person to whom they belong, the concrete interests of an unspecified number of persons, beyond merely absorbing and dissolving them into the general public interest," then such interests qualify as "legally protected interests." Whether a statute has such an aim is determined by considering "the purpose and objective of the said administrative statute, and the content and nature of the interests that the said administrative statute seeks to protect through the said disposition."

II. Standing Affirmed for Residents Fearing Direct Disaster to Life and Body

Applying this standard, the Court first examined the Forest Act provisions related to disaster prevention – Article 10-2, Paragraph 2, Item 1 (risk of landslides, soil runoff, or other disasters) and Item 1-2 (risk of flooding).

- The Court interpreted these provisions as being intended not only to ensure the public interest functions of forests in preventing disasters but also "to protect, as individual interests of each person, the life, body, safety, etc., of residents in a certain range of areas adjacent to the development area who are assumed to be directly affected by such disasters such as landslides or floods."

- Regarding plaintiffs X1 and X2, the Court noted the following facts: the proposed golf course development was large (117 hectares) and located in the upstream area of the Kozato River, which had experienced two floods in the past. X1 and X2 resided downstream, near this river, in an area with little elevation difference from the development site. Furthermore, this was one of six golf course projects planned in the same river basin.

- Based on these specific circumstances, the Supreme Court found it "appropriate to recognize" that X1 and X2 were "persons residing in an area expected to suffer direct damage from disasters such as landslides or floods" that could result from the development. Therefore, they had a legally protected interest and thus standing to challenge the permit.

III. Standing Denied for Primarily Property or Water-Use/Environmental Interests

The Court then considered the standing of the other plaintiffs (X3-X7) based on their asserted interests:

- Property Rights (X3-X6): These plaintiffs owned trees or land either within or near the development area. However, the Court found it "difficult to read" into the disaster prevention clauses (Article 10-2(2)(i) and (i-2)) an intent to protect "property rights such as ownership of surrounding land as individual interests" in addition to the protection of residents' life and bodily safety.

- Water Use and General Environmental Interests (X7 and implicitly others): Article 10-2, Paragraph 2, Item 2 concerns the risk of "significant hindrance to the securing of water" in areas dependent on the forest's water retention functions. Item 3 concerns the risk of "significant deterioration of the environment of the surrounding area." The Supreme Court interpreted both these provisions as being "understood from a public interest perspective of securing water resources or preserving a good environment" and concluded that they "cannot be construed as including the aim of protecting the individual interests of surrounding residents, etc."

- Consequently, X3-X6 (the tree/land owners) and X7 (the farmer concerned about water for agriculture from the river) were found not to have the necessary legal interest for standing under these provisions.

Unpacking the "Legally Protected Interest" in Environmental Cases

This 2001 Supreme Court decision is significant for how it applied the "legally protected interest" standard in the context of environmental and development disputes.

Focus on Direct Threat to Life and Body

The judgment clearly prioritized direct threats to personal safety (life and body) as a basis for recognizing individual standing under specific disaster prevention clauses of the Forest Act. Residents whose homes were geographically situated such that they faced a credible risk of landslides or flooding from the development were deemed to have their individual safety interests protected by these clauses.

Reluctance to Recognize Individual Property/Economic/General Environmental Interests under these Forest Act Clauses

The Court's denial of standing to landowners concerned about property damage (under the disaster clauses) and to the farmer concerned about water resources (under the water resource protection clause) is a key aspect of the ruling. The PDF commentary accompanying this case is critical of this distinction, particularly regarding property. It argues that property damage from disasters like landslides or floods is a very direct, foreseeable, and individual harm, making it difficult to understand why the Forest Act's disaster prevention clauses would not also be interpreted as protecting these individual property interests. The Supreme Court's reasoning seems to imply that, under these specific provisions of the Forest Act, such property interests are perhaps considered "absorbable into the general public interest" more readily than direct threats to life and bodily safety.

Similarly, the Court's interpretation of the Forest Act's clauses on water resource protection and general environmental protection as serving only the general public interest, without conferring individually protected interests on those who rely on those resources (like farmer X7) or who live in the affected environment, demonstrates a cautious approach to broadening standing for these types of claims based on the Forest Act's specific wording.

The Scope of "Area Assumed to Suffer Direct Damage"

For the residents whose standing was affirmed (X1 and X2), the Court emphasized that the determination of whether they fell within the "area assumed to suffer direct damage" is a fact-specific inquiry. It requires consideration of the reactor's (in Monju, or the development's in this case) type, structure, scale, and, crucially, the distance relationship between the facility and the residents' homes, all to be "reasonably judged in light of societal norms." This flexible standard allows for case-by-case assessment but also introduces an element of judicial discretion in defining the geographical limits of standing.

Implications for Environmental Litigation

The 2001 Forest Land Development Permit case has several important implications for environmental litigation in Japan:

- It confirmed a pathway for standing for residents facing direct threats to their personal safety from development projects, provided that the relevant statutes can be interpreted as intending to protect such individual safety interests.

- However, it also underscored that establishing standing for harms to property, economic interests (like water for agriculture), or general environmental quality can be more challenging. Plaintiffs in such cases must demonstrate that the specific statutory provisions they rely on are intended to protect their interests as individual ones, not just as part of the general public welfare. This often requires a very close reading and interpretation of the particular law in question.

- The case highlights that the "legally protected interest" test, while providing a framework, still allows for considerable judicial interpretation regarding the protective scope of different statutory provisions and the types of harm deemed to confer individual standing.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2001 decision in the Gifu golf course development case is a significant judgment that refined the application of the "legally protected interest" standard for plaintiff standing in environmental disputes in Japan. It affirmed standing for residents who faced a direct and foreseeable threat to their life and bodily safety from potential disasters linked to the forest development, based on the Court's interpretation of the specific protective purpose of certain clauses within the Forest Act.

However, by denying standing to landowners whose primary concern was property damage under those same disaster clauses, and to a farmer concerned about water resources under a separate environmental clause of the Act—interpreting those provisions in those contexts as solely safeguarding general public interests—the Court maintained a relatively high bar for many types of environmental and economic injury claims. The decision underscores that the ability of citizens to challenge development projects often hinges on a detailed and sometimes restrictive judicial interpretation of the specific protective scope of the relevant environmental and land use laws. It emphasizes that not all adverse impacts from development will automatically grant an individual the right to sue; a clear link to an individually protected legal interest, as intended by the specific statute, must be established.