Foreseeability's Reach: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Reckless Driving and the Unforeseen Victim

Decision Date: March 14, 1989

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

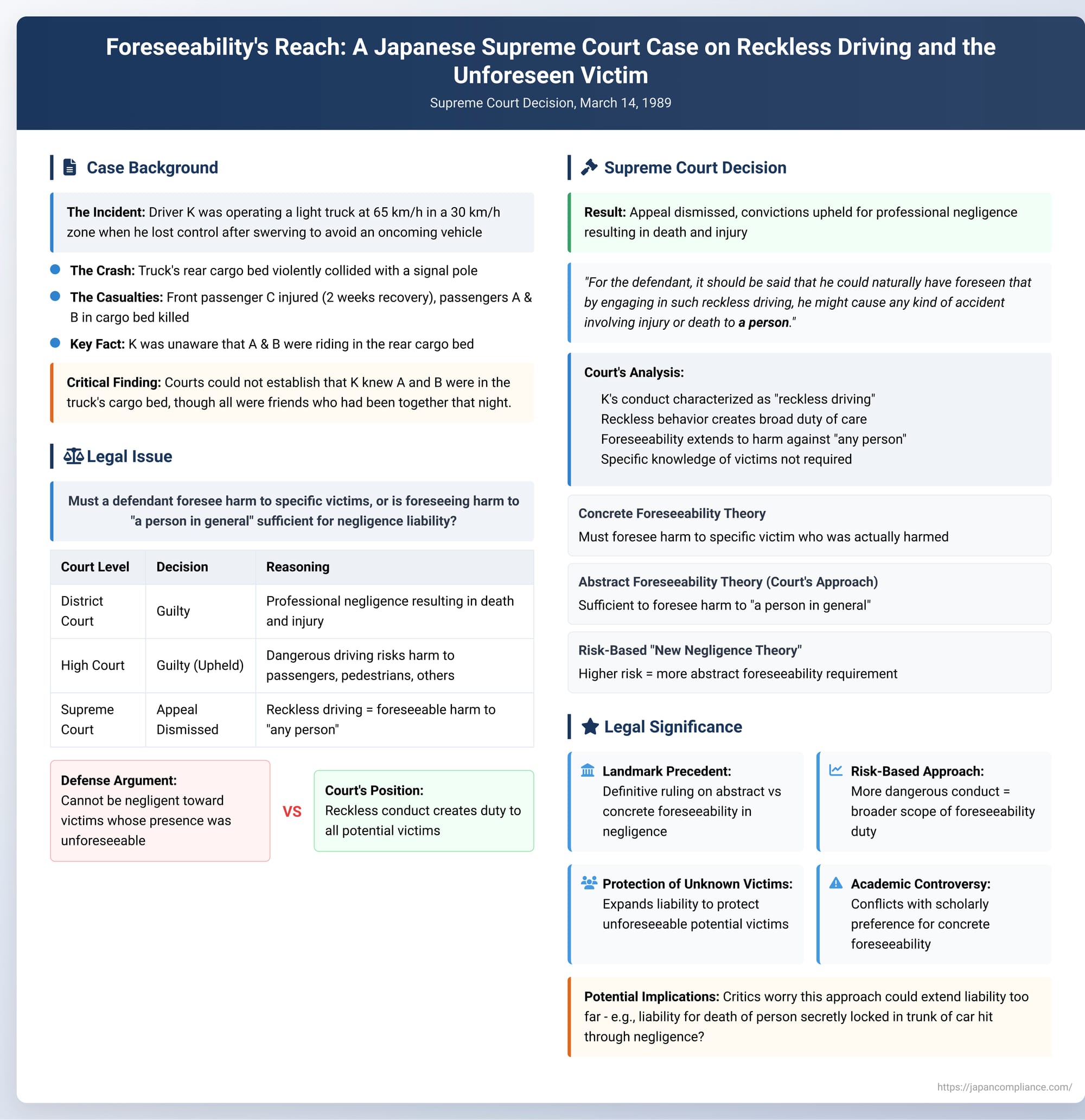

In the realm of criminal negligence, the concept of "foreseeability" serves as a crucial gatekeeper for liability. An individual is typically held responsible only for consequences they could have reasonably predicted. But what, precisely, must be foreseen? Must the specific victim and the exact manner of harm be anticipated, or is a more general premonition of danger sufficient? A 1989 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan confronts this fundamental question head-on, in a case involving a fatal traffic accident with a startling twist: the driver was found not to have been aware that the victims who died were even in his vehicle.

This ruling provides a masterclass in the Japanese legal system's analysis of negligence, particularly concerning the required scope and object of foreseeability. It scrutinizes the relationship between the degree of risk created by an act and the level of specificity required in foreseeing the potential harm, ultimately clarifying the conditions under which one can be held liable for the death of a person whose very presence was unknown.

Factual Background

The defendant, K, was operating a light commercial truck for work purposes. He was driving on a road with a designated maximum speed limit of 30 km/h, but was traveling at an excessive speed of approximately 65 km/h. While driving, he was startled by an oncoming vehicle and reacted erratically. He swerved sharply to the left, nearly hitting a guardrail, and then overcorrected with a sudden, sharp turn to the right. This caused him to lose control of the truck, which then careened wildly before its rear left cargo bed violently collided with a signal pole on the left side of the road.

The impact of the crash had tragic consequences for his passengers. C, a friend seated in the front passenger seat, sustained injuries requiring about two weeks of recovery. However, A and B, two other friends who were riding in the open rear cargo bed of the truck, were killed.

The critical and most challenging factual finding by the courts was that it could not be definitively established that K was aware of the fact that A and B were riding in the rear cargo bed of his truck. All three passengers were his friends, and they had been together that night, but the prosecution could not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that K knew A and B had climbed into the back.

The Legal Issue: From the Lower Courts to the Supreme Court

The Tokyo District Court, as the court of first instance, found K guilty of professional negligence resulting in death and injury. This verdict was upheld by the Tokyo High Court on appeal. The High Court’s reasoning was pivotal. It asserted that any driver should naturally recognize that operating a vehicle in such a dangerous manner risks causing injury or death to fellow passengers, pedestrians, or occupants of other vehicles. Therefore, even if K was not specifically aware that A and B were in the cargo bed, he could not escape criminal liability for their deaths.

As a supplemental point, the High Court noted that it was plausible K could have recognized their presence. It reasoned that people riding in the back of such trucks was not an extremely unusual occurrence, and K might have seen them or felt the vehicle's movement as they boarded.

Unsatisfied with this reasoning, K's defense counsel appealed to the Supreme Court. The appeal centered on the very definition of foreseeability. The defense argued, in essence, that one cannot be held negligent for a result involving victims whose presence was unforeseeable. If K did not know A and B were in the truck, how could he have foreseen a risk of harm to them?

The Supreme Court's Decision

On March 14, 1989, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, affirming the lower courts' verdicts. The Court's decision was concise but powerful, articulating a clear legal principle.

The Court began by characterizing K's conduct as "driving that could be described as reckless." It then laid out its core reasoning:

"For the defendant, it should be said that he could naturally have foreseen that by engaging in such reckless driving, he might cause any kind of accident involving injury or death to a person. Therefore, even if the defendant did not recognize the fact that the two aforementioned individuals were riding in the rear cargo bed of his vehicle, this should not preclude the establishment of the crime of professional negligence resulting in their deaths. The original judgment, which is to the same effect, is proper."

In this single paragraph, the Supreme Court established a direct link between the recklessness of the conduct and the scope of foreseeability. Because K's driving was so egregiously dangerous, the object of his foreseeable duty of care was not limited to specific, known individuals. Instead, it was broadened to encompass a general, abstract "person" who might be harmed by his actions. The lack of specific knowledge about the victims in the cargo bed was, in the Court's view, legally irrelevant in the face of such manifest recklessness.

Analysis: The Object of Foreseeability in Japanese Negligence Law

This decision is a cornerstone in the Japanese jurisprudence of criminal negligence (kashitsu-han), as it directly addresses the contentious issue of foreseeability's "object." While there is no dispute that foreseeability is an essential prerequisite for negligence, fierce debate exists over what must be foreseen. The 1989 ruling offers the judiciary's clear answer, which can be best understood by examining the competing academic theories.

The Central Question: Foreseeability of Whom?

The case boils down to a fundamental conflict between two views on foreseeability:

- Concrete Foreseeability: This view requires that the defendant must have been able to foresee the possibility of the harmful result occurring to the specific victim who was actually harmed.

- Abstract Foreseeability: This view holds that it is sufficient for the defendant to have foreseen the possibility of that type of harm occurring to a person in general.

The defense's argument was rooted in the principle of concrete foreseeability. The Supreme Court, however, decisively adopted a form of abstract foreseeability.

Competing Legal Theories

Japanese legal scholarship has long debated this point, often by drawing analogies to the separate legal issue of "mistake of fact" in intentional crimes.

- The "Concrete" View (Analogy to Concrete Correspondence Theory): Many scholars argue that, for the sake of legal consistency, the standard for negligence should mirror the dominant theory for intentional crimes. In cases of mistake, this theory (gutaiteki-fugosetsu) requires that the intended victim and the actual victim align concretely for intent to be established. By analogy, this camp argues that for negligence, the defendant must have been able to foresee harm to the specific person who was ultimately victimized. From this perspective, the Supreme Court's decision is incorrect. If K could not have foreseen the presence of A and B, he could not be negligent with respect to their deaths.

- The "Abstract" View (Analogy to Statutory Correspondence Theory): Another camp draws an analogy to a different theory of mistake (hoteiteki-fugosetsu), which holds that intent is established as long as the actual result matches the statutory definition of the crime the defendant intended to commit, even if the victim is different. By this logic, as long as K could foresee causing death or injury to "a person," his negligence is established, and the Supreme Court's decision is correct. However, critics point out that even this theory for intentional crimes presupposes that the actual result was, in itself, foreseeable, making it a weak foundation for expanding liability to an unforeseeable victim.

- The Risk-Based "New Negligence Theory": A more modern and influential school of thought, often called the "new negligence theory" (shin-kashitsuron), breaks away from analogies to intentional crimes and analyzes negligence on its own terms. This theory posits that foreseeability is a concept that serves to establish a "duty to avoid a harmful result." The key insight of this approach is that the nature of this duty is inversely proportional to the level of risk created by the defendant's conduct.The higher the degree of danger created by the act, the more stringent the duty of care, and correspondingly, the more abstract the object of foreseeability becomes.The Supreme Court's 1989 decision aligns perfectly with this risk-based approach. The Court's explicit labeling of K's driving as "reckless" and creating a "diffusion of danger" was the critical first step. Because the conduct was so inherently and indiscriminately dangerous, the Court imposed a high duty of care and, consequently, lowered the required specificity of foreseeability. It was no longer necessary to foresee harm to A and B specifically; foreseeing harm to "a person" was sufficient.

Implications and The Outer Limits of Liability

The logic of the 1989 decision provides a robust tool for holding perpetrators of highly dangerous activities accountable, even for unexpected outcomes. However, it also raises unsettling questions about the potential for over-extended liability.

Legal commentators have pointed to a troubling hypothetical: imagine a driver who, through gross negligence, rear-ends another car. Unbeknownst to anyone, a person was secretly locked in the trunk of the car that was hit, and this person dies as a result of the collision. Following the abstract logic of the 1989 decision, could the negligent driver be held liable for the death of this utterly unforeseeable victim? The act of causing a major collision through gross negligence is highly dangerous. If the foreseeability requirement is abstracted to merely "injury or death to a person," one could argue for liability even in this extreme scenario. While the facts of the trunk case may be distinguishable from the 1989 decision (where the victims were friends of the driver and in a part of the vehicle, the cargo bed, where passengers are not entirely unheard of), the underlying legal principle of the ruling contains the potential to stretch the bounds of negligence into uncomfortable territory.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 14, 1989 decision is a landmark ruling in the landscape of Japanese criminal law. It clarifies that in cases of negligence involving exceptionally dangerous or "reckless" conduct, the foreseeability requirement is satisfied by an abstract prediction of harm to "a person in general." The prosecution does not need to prove that the defendant could have foreseen the presence of the specific victim who was ultimately harmed.

The ruling can be seen as a judicial endorsement of a risk-based approach to negligence, where the scope of one's duty of care expands in direct proportion to the danger one creates. While this provides a strong basis for accountability in cases of egregious misconduct, it also challenges the legal system to remain vigilant in defining the reasonable outer limits of criminal responsibility for the unforeseen.