Foreign Patents, Japanese Courts: Supreme Court Tackles Cross-Border Infringement Claims

Date of Judgment: September 26, 2002

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

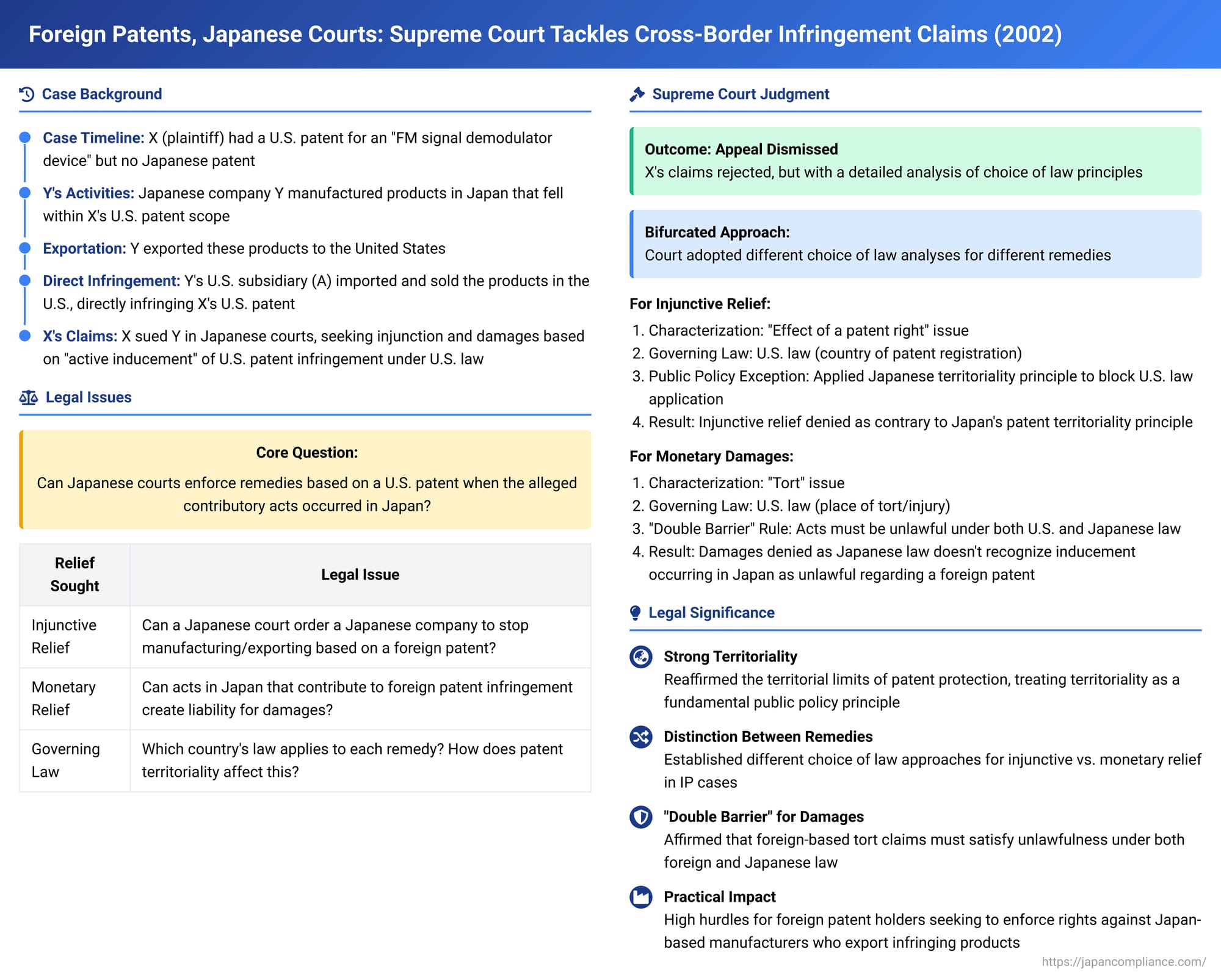

In an era of global commerce, intellectual property rights, particularly patents, often find their protective reach tested across international borders. A significant issue arises when activities in one country, which may not directly infringe a patent there (perhaps because no corresponding patent exists), contribute to or "induce" the infringement of a patent in another country. The Japanese Supreme Court, in a pivotal decision on September 26, 2002, addressed such a scenario, clarifying how Japanese courts handle claims based on the infringement of a foreign patent where the alleged contributory acts occur within Japan. This case provides deep insights into the application of private international law principles, including the territoriality of patent rights, choice of law for different remedies, and the public policy exception.

The Factual Scenario: Manufacturing in Japan, Infringement in the U.S.

The dispute involved the following key elements:

- X (Plaintiff/Appellant): Held a United States patent for an "FM signal demodulator device" (the "U.S. Patent"). Notably, X did not possess a corresponding patent for this invention in Japan.

- Y (Defendant/Appellee): A Japanese company that manufactured card reader products ("Y Products") in Japan. These Y Products fell within the technical scope of X's U.S. Patent.

- Y's Actions and U.S. Infringement: Y exported its Y Products from Japan to the United States. These products were then imported and sold in the U.S. by A, Y's wholly-owned U.S. subsidiary. The sales by A in the U.S. constituted the direct infringement of X's U.S. Patent.

- X's Lawsuit in Japan: X sued Y in a Japanese court. X alleged that Y's activities in Japan—manufacturing the Y Products for export to the U.S., the actual exportation, and actively inducing its U.S. subsidiary A to sell the products in the U.S.—constituted "active inducement" of patent infringement under U.S. patent law (specifically, 35 U.S.C. §271(b)).

X sought two primary forms of relief from Y:- Injunctive Relief: An order to stop Y from manufacturing the Y Products in Japan for export to the U.S., from exporting them to the U.S., and from inducing A to sell them in the U.S. X also sought an order for the destruction of any Y Products in Y's possession in Japan.

- Monetary Relief: Damages for the tort of patent infringement (with an alternative claim for restitution for unjust enrichment for any parts of the claim that might be time-barred).

The lower courts had largely dismissed X's claims, with the Tokyo High Court notably reasoning that Japanese courts could not grant injunctive relief based on a foreign patent due to the principle of territoriality, suggesting no choice of law question even arose for that remedy.

The Supreme Court's Bifurcated Approach to Foreign Patent Claims

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, but its detailed reasoning significantly clarified the approach Japanese courts should take. The Court notably distinguished between the choice of law analysis for injunctive relief and that for monetary damages.

A preliminary, yet crucial, point made by the Supreme Court was that while the principle of patent territoriality (meaning a patent's effects are confined to the territory of the granting country) is recognized, this does not negate the need for Japanese courts to undertake a choice of law analysis when faced with private disputes concerning foreign patent rights. This directly addressed and corrected the High Court's stance on injunctive relief.

Injunctive Relief (Injunction and Destruction of Goods)

- Characterization of the Legal Issue: The Supreme Court characterized X's claims for an injunction and destruction of goods based on the U.S. Patent not as tort claims (which primarily aim to compensate for past harm) but as claims stemming from the "exclusive monopolistic effect of the U.S. Patent". Therefore, the legal nature of this issue was determined to be the "effect of a patent right."

- Governing Law for "Effect of a Patent Right": Japan's private international law rules (the Horei, at the time) had no explicit provision for determining the governing law for the "effect of a patent right." The Supreme Court, invoking jōri (reason or natural justice), determined that the governing law should be that of the country with the "most significant relationship" to the patent right. This country, the Court reasoned, is the country where the patent was registered—in this case, the United States.

The rationale for this choice included: (a) patents are granted through national application and registration processes; (b) many countries adhere to the principle of territoriality, meaning the patent's validity and effect are governed by national law and confined to national territory; and (c) given this territorial effect, the country where protection for the patent is primarily sought is its registration country, making it the most closely connected.

Thus, U.S. law was deemed the governing law for X's claims for injunctive relief. - The Territoriality Hurdle (Applied as Public Policy):

The Court then considered the application of U.S. patent law. It acknowledged that U.S. law (specifically 35 U.S.C. §271(b) regarding inducement and §283 regarding injunctions) could potentially allow for injunctive relief and destruction orders against Y's acts of inducement in Japan, given the direct infringement in the U.S..

However, the Supreme Court invoked Japanese public policy (公の秩序 - kō no chitsujo, under Horei Article 33, similar to Article 42 of the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws) to block this outcome. It reasoned:- Japan adheres to the principle of patent territoriality, meaning a Japanese patent has effect only within Japan, and by extension, foreign patents generally have effect only in their granting territories.

- To grant an injunction in Japan against Y's manufacturing and export activities in Japan, based on a U.S. patent, would effectively give extraterritorial effect to the U.S. patent within Japan. This, the Court found, would contradict the fundamental principle of territoriality as adopted by Japan.

- Furthermore, there was no treaty between Japan and the United States requiring mutual recognition of such patent effects within each other's territories.

- Therefore, applying U.S. patent law to order an injunction against actions within Japan or the destruction of goods located in Japan, due to inducement of U.S. patent infringement, would be "incompatible with the fundamental principles of Japan's patent law order."

- Consequently, the relevant provisions of U.S. patent law authorizing such relief were not applied, and X's claims for an injunction and destruction were dismissed for lacking a legal basis under this framework.

Monetary Relief (Damages)

- Characterization of the Legal Issue: The Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts that a claim for damages due to patent infringement is not an issue unique to patent law but rather a form of civil remedy for the infringement of property rights. Thus, its legal nature was characterized as a "tort" (不法行為 - fuhō kōi).

- Governing Law for Tort (Lex Loci Delicti): The governing law for torts under Horei Article 11(1) was the law of the "place where the facts constituting the cause of the tort occurred" (原因タル事実ノ発生シタル地 - gen'in taru jijitsu no hassei shitaru chi). The Supreme Court identified this place as the United States, where the direct infringement of the U.S. Patent by subsidiary A occurred and where the injury (the infringement of X's rights) was sustained. This was a departure from the High Court, which had considered Japan (Y's place of action) as the relevant location.

The Supreme Court's rationale for choosing the U.S. was: (a) if Y's actions in Japan actively induced infringement of the U.S. patent, the injurious result (the direct infringement) occurred in the U.S.; and (b) applying U.S. law would not harm Y's predictability, especially since Y intended for its U.S. subsidiary to import and sell the products in the U.S.. - The "Double Barrier" – Cumulative Application of Japanese Law (Horei Article 11(2)):

While U.S. patent law (e.g., 35 U.S.C. §271(b) for inducement and §284 for damages) might establish Y's liability for damages for actively inducing infringement in the U.S. via acts performed in Japan, Japanese private international law imposed an additional condition. Horei Article 11(2) (the principles of which are now, with modification, in Article 22(1) of the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws) stipulated that facts occurring in a foreign country that would give rise to a claim under foreign law would only do so if those facts also constituted a tort under Japanese law.

The Supreme Court then examined Y's conduct under Japanese law. It found that:- Japan adheres to the principle of patent territoriality.

- Unlike U.S. patent law, Japanese patent law does not contain provisions that explicitly extend the effect of a patent to cover acts of "active inducement" performed outside the patent-granting country.

- Therefore, unless specific legislation or a treaty provides otherwise, acts performed in Japan (outside the territory of the U.S. patent) that actively induce infringement of a U.S. patent cannot be considered "unlawful" under Japanese law in a way that would satisfy the requirements for a tort claim based on that foreign patent infringement.

- The Court concluded that the infringement of X's U.S. Patent, in these circumstances, constituted "facts occurring in a foreign country which are not unlawful under Japanese law" as per Horei Article 11(2).

- As a result, the provisions of U.S. patent law allowing for damages could not be applied to Y's actions, and X's damages claim was dismissed.

(It's noteworthy that Justice Fujii provided a dissenting opinion on the damages claim, arguing that inducement of a U.S. patent infringement could still constitute a tort under general Japanese civil law principles of joint tortfeasance (aiding or abetting), even without specific extraterritorial provisions in Japanese patent law, once the existence of the U.S. patent was acknowledged.)

Significance and Commentary Insights

This Supreme Court decision was a landmark in clarifying the complex choice of law issues surrounding the enforcement of foreign patent rights in Japanese courts, particularly against acts of inducement occurring within Japan.

Key takeaways and points from academic commentary (such as by Professor Shimanami) include:

- Bifurcated Approach: The Court's distinct treatment of injunctive relief (as an "effect of patent right") and damages (as a "tort") is a defining feature of the judgment, though this separation has drawn some criticism for potentially fragmenting the analysis of what is essentially a single underlying wrong.

- Territoriality as Public Policy: The use of Japan's principle of patent territoriality as the specific content of "public policy" to preclude the application of U.S. law for injunctive relief was a notable and somewhat controversial aspect. Critics have questioned whether a principle defining the spatial scope of laws (territoriality) fits neatly within the concept of public policy, which usually pertains to fundamental substantive values or the shocking results of applying foreign law.

- Lex Loci Delicti for Damages: The Supreme Court's determination that the "place where the facts constituting the cause of the tort occurred" was the place of the direct infringement and injury (the U.S.) for an international inducement claim, rather than the place of the inducing act (Japan), represented a significant choice. This result-oriented approach for identifying the locus delicti in cross-border torts has since been reflected in legislative reforms (e.g., Article 17 of the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws).

- Cumulative Application and Its Impact: The application of Horei Article 11(2) effectively meant that even if U.S. law provided a remedy for Y's inducement, the lack of a corresponding basis for unlawfulness under Japan's territorially-focused patent system for such out-of-country inducement prevented recovery. Justice Fujii's dissent highlighted an alternative interpretation where general tort principles under Japanese law might still capture such inducement as a form of complicity.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2002 judgment establishes a high bar for holders of foreign patents seeking to enforce their rights in Japanese courts against parties engaging in preparatory or contributory acts within Japan. While acknowledging that foreign law (specifically, the law of the patent-issuing country) is, in principle, the governing law for determining the effects of a foreign patent and for torts arising from its infringement abroad, the Court demonstrated that the application of that foreign law can be significantly constrained. For injunctive relief, Japan's adherence to the principle of patent territoriality can act as a public policy shield against enforcing foreign patent rights extraterritorially within Japan. For damages, the requirement that the conduct also be deemed unlawful under Japanese law (which itself is territorially limited in its patent scope) presents a further substantial hurdle. This decision underscores the strong influence of the territoriality principle in international intellectual property litigation in Japan.