No Statutory Welfare Right for Foreign Residents: Japan Supreme Court Public Assistance Ruling (2014)

Japan's Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that foreign residents have no Public Assistance Act welfare right; aid depends on administrative discretion.

TL;DR

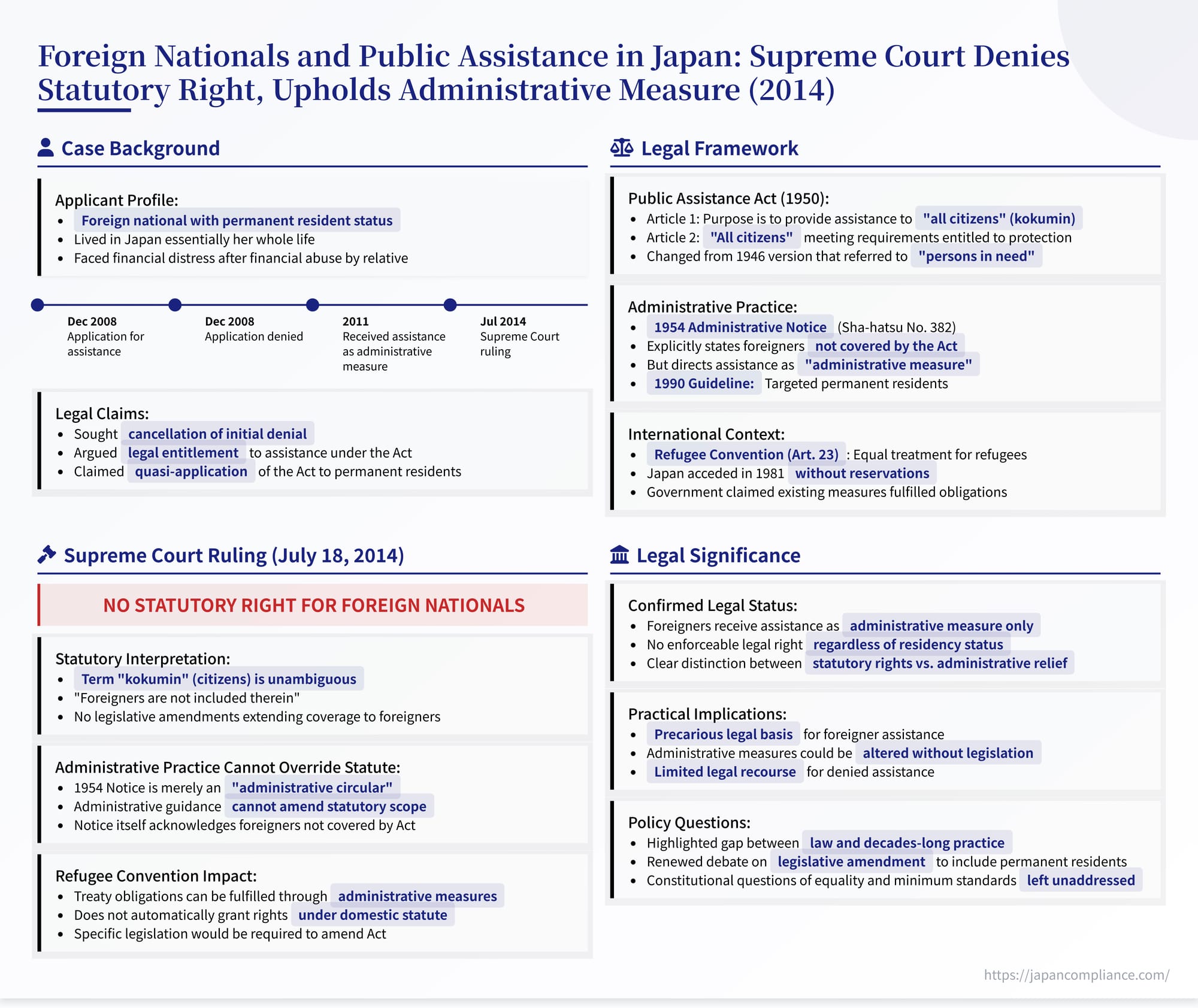

Japan’s Supreme Court (July 18 2014) ruled that foreign residents—including permanent residents—have no statutory right to benefits under the Public Assistance Act; any aid is granted only as a discretionary administrative measure. The decision clarifies the gulf between statutory entitlements and long‑standing practice and raises policy questions about future protection for non‑citizens.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Permanent Resident’s Plea for Assistance

- Legal Framework: Public Assistance Act and Foreign Nationals

- Lower Court Ruling: Quasi‑Application for Permanent Residents

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis: No Statutory Right for Foreigners

- Outcome of the Case

- Implications and Significance: Drawing a Line Between Law and Practice

- Conclusion

On July 18, 2014, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment addressing a long-standing and fundamental question regarding Japan's social safety net: Do foreign nationals residing in Japan, particularly those with permanent resident status, have a legally enforceable right to receive benefits under the Public Assistance Act (Seikatsu Hogo Hō - 生活保護法)? (Case No. 2012 (Gyo-Hi) No. 45, "Life Protection Commencement Decision Obligation etc. Claim Case"). Despite decades of administrative practice providing assistance to certain foreigners, the Supreme Court concluded that the Act, by its explicit terms, applies only to Japanese citizens. It held that foreign nationals do not possess a statutory right to protection under the Act itself, affirming that the assistance provided to them is based on administrative measures and policy, not legal entitlement derived directly from the statute. This decision clarified the legal basis (or lack thereof) for foreigner access to Japan's primary public assistance program and highlighted the distinction between statutory rights and discretionary administrative relief.

Factual Background: A Permanent Resident's Plea for Assistance

The case involved an elderly foreign national facing significant hardship:

- The Applicant: The appellee, X, was a woman of foreign nationality residing in Japan with permanent resident status (永住者 - eijūsha). She had lived in Japan essentially her whole life.

- Circumstances Leading to Application: X and her husband (also a foreign national with permanent resident status) had previously run a restaurant. After the husband fell ill around 1978, they lived on rental income from properties. In 2004, her husband was hospitalized with dementia. From around April 2006, X began living with her husband's younger brother, who subsequently abused her (physical violence, verbal abuse) and took control of her finances (bank books, seals), leaving her in severe financial distress (seikatsu ni konkyū suru yō ni natta). X later required hospitalization herself but could not afford the costs, and upon recovery, feared returning home due to her brother-in-law, eventually moving into a facility run by a non-profit organization.

- Public Assistance Application and Denial: On December 15, 2008, X applied for public assistance under the Public Assistance Act at the Oita City Welfare Office. On December 22, 2008, the Welfare Office Director issued a decision denying her application ("the Denial Decision"), citing the existence of considerable savings held in bank accounts under X's and her husband's names as the reason for ineligibility (i.e., she did not meet the financial need criteria).

- Administrative Appeal and Subsequent Assistance: X appealed the Denial Decision to the Oita Prefectural Governor. The Governor dismissed the appeal, not on the merits, but on the procedural ground that the Denial Decision did not constitute an "administrative disposition" subject to appeal under the Administrative Appeal Act because, in the Governor's view, foreigners lack legally protected rights under the Public Assistance Act itself. (Separately, X later reapplied for assistance and began receiving it as an administrative measure from October 26, 2011).

- Lawsuit: Despite eventually receiving assistance, X pursued a lawsuit against Oita City (Y, the appellant) seeking the cancellation of the initial Denial Decision and an order compelling the city to make a commencement decision based on her original application, arguing that the denial was illegal because she was legally entitled to protection under (or through quasi-application of) the Public Assistance Act.

Legal Framework: Public Assistance Act and Foreign Nationals

The case required interpretation of Japan's core social assistance law and the long-standing administrative practice concerning foreigners:

- Public Assistance Act (生活保護法 - Seikatsu Hogo Hō, 1950):

- Article 1 (Purpose): States the Act aims, based on the ideals of Constitution Article 25 (right to minimum standards of living), for the State to provide necessary protection to "all citizens (kokumin) who are in need" according to their level of need, guarantee their minimum standard of living, and promote their self-reliance.

- Article 2 (Principle of Non-Discrimination): States that "all citizens (kokumin)" meeting the Act's requirements are entitled to protection under the Act without discrimination.

- Contrast with Old Act (1946): The previous (now repealed) Public Assistance Act did not use the term "citizens" (kokumin) in its purpose clause (Art. 1), instead referring broadly to "persons in need of public assistance." The inclusion of "kokumin" in the current 1950 Act was a key point of interpretation.

- Constitution Article 25: Guarantees all kokumin the right to maintain minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living and obligates the State to promote social welfare, security, and public health. The extent to which this right extends to foreign nationals is a long-standing constitutional debate in Japan.

- Administrative Notice (Showa 29 [1954] Sha-hatsu No. 382): A pivotal administrative circular issued by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. It explicitly states that foreigners are not covered by the Public Assistance Act. However, it directs local authorities, "for the time being" (tōbun no aida), to provide necessary assistance to foreigners in need as an "administrative measure" (gyōsei sochi), applying procedures and standards similar to those used for Japanese citizens, contingent on confirming the foreigner cannot receive support from their home country's representatives.

- 1990 Guideline: An internal Ministry guideline further clarified that the target of this administrative measure should primarily be foreigners with stable residency statuses, such as permanent residents and certain others listed in Table 2 of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (often referred to as "永住的外国人 - eijūteki gaikokujin").

- Refugee Convention (Article 23): Requires contracting states to accord refugees lawfully staying in their territory the same treatment with respect to public relief and assistance as is accorded to their nationals. Japan acceded to the Convention without reservations in 1981.

Lower Court Ruling: Quasi-Application for Permanent Residents

The High Court (Fukuoka High Court) had found in favor of X on the issue of legal standing and the applicability of the law. It reasoned that:

- Japan's accession to the Refugee Convention without reservation, coupled with government statements during parliamentary deliberations suggesting that the existing administrative measures (the 1954 Notice) fulfilled the Convention's requirements, indicated an implicit recognition by the legislative and executive branches that certain foreigners had a legally protected status equivalent to that under the Public Assistance Act.

- The subsequent 1990 administrative guideline limiting the de facto assistance primarily to permanent residents etc., further suggested that this administrative practice was intended as a quasi-application (jun'yō) of the Act itself to this specific group.

- Therefore, X, as a permanent resident, had a legally protected interest derived from the quasi-application of the Act, making the Denial Decision reviewable and potentially unlawful on the merits.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (July 18, 2014): No Statutory Right for Foreigners

The Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's interpretation and definitively ruled that the Public Assistance Act does not confer legally enforceable rights upon foreign nationals, including permanent residents.

1. Strict Statutory Interpretation:

- The Court focused heavily on the text of the current (1950) Public Assistance Act. It highlighted the explicit shift in wording from the Old Act (which covered all "persons in need") to the current Act's Articles 1 and 2, which specifically refer to "citizens" (kokumin).

- The Court held that, in the context of the Public Assistance Act, "kokumin" unambiguously means Japanese nationals and "foreigners are not included therein." (gaikokujin wa kore ni fukumarenai).

2. Lack of Subsequent Legislation:

- The Court emphasized that since the 1950 Act was enacted, no legislative amendments have been made to extend its coverage to foreigners or to provide a legal basis for its quasi-application (jun'yō) to them.

3. Administrative Notice Cannot Amend the Law:

- The Court addressed the long-standing administrative practice based on the 1954 Notice. It classified the Notice as merely an "administrative circular" (gyōseichō no tsūtatsu).

- While this circular established the practice of providing de facto protection as an "administrative measure" (gyōsei sochi), such administrative guidance cannot legally override or amend the scope of the statute itself as enacted by the legislature.

- Furthermore, the Court noted that the Notice's own text explicitly proceeds on the premise that foreigners are not legally covered by the Act, reinforcing that the assistance provided is distinct from statutory entitlement.

4. Refugee Convention Does Not Confer Statutory Rights Under Domestic Law:

- The Court rejected the High Court's reasoning regarding the implications of the Refugee Convention. While acknowledging Japan's obligations under the treaty, the Court stated that fulfilling those obligations through existing administrative measures (as the government claimed during accession) does not automatically grant foreigners legal rights under the specific domestic statute (the Public Assistance Act).

- Accession to a treaty does not, in itself, amend domestic laws like the Public Assistance Act that explicitly limit their scope to citizens. If the existing administrative measures were deemed insufficient to meet treaty obligations, specific legislative action would be required to grant foreigners statutory rights under the Act.

5. Conclusion: Foreigners Only Eligible for Administrative Measures:

Based on the clear statutory text limiting coverage to "citizens" and the lack of any subsequent legal basis (either through legislation or treaty interpretation) to extend statutory rights to foreigners, the Supreme Court concluded:

- "Foreigners are only eligible to become recipients of de facto protection through administrative measures based on administrative circulars, etc.; they are not persons covered by the Public Assistance Act based protection, and do not possess a right to receive benefits (jukyūken) under the said Act." (Gaikokujin wa,... gyōsei sochi ni yori jijitsu-jō no hogo no taishō to nariuru ni todomari, Seikatsu Hogo Hō ni motozuku hogo no taishō to naru mono de wa naku, dōhō ni motozuku jukyūken o yūshinai mono to iu beki de aru.)

Outcome of the Case

Since X, being a foreign national, possessed no legal right to receive benefits under the Public Assistance Act, her application based on the Act was legally unfounded. Therefore, the Oita City Welfare Office Director's decision denying that application ("the Denial Decision") was lawful (tekihō) in the sense that it correctly refused a claim based on a non-existent statutory entitlement. The High Court's finding that the Act quasi-applied to permanent residents was erroneous. The Supreme Court reversed the High Court and reinstated the first instance judgment dismissing X's claim for cancellation of the Denial Decision (as it pertained to her claim under the Act).

Implications and Significance: Drawing a Line Between Law and Practice

This 2014 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark decision with significant implications for the rights of foreign residents in Japan:

- Confirms Exclusion from Statutory Public Assistance: It definitively establishes, at the highest judicial level, that foreign nationals, regardless of their residency status (including permanent residents), do not have a legally enforceable right to receive benefits directly under Japan's Public Assistance Act.

- Upholds Administrative Measure Framework: It confirms that the assistance provided to needy foreign residents for decades is legally characterized as a discretionary "administrative measure" based on the 1954 Notice, rather than a statutory entitlement. This assistance is provided despite, not because of, the Public Assistance Act's provisions.

- Potential Precarity for Foreign Residents: While not immediately changing the practice of providing assistance to eligible permanent residents and others covered by the administrative guidelines, the ruling highlights the potentially precarious legal basis for this support. As an administrative measure, it could theoretically be altered or discontinued by administrative policy changes without requiring legislative amendment, unlike the statutory rights of citizens.

- Limits Legal Recourse: Foreigners denied this administrative assistance cannot sue based on a right under the Public Assistance Act. While challenges based on abuse of discretion in applying the administrative measure might be theoretically possible, the lack of a clear statutory basis makes such challenges complex.

- Reignites Legislative Debate: The decision starkly contrasts the explicit exclusion in the law ("citizens") with the long-standing inclusive administrative practice. This discrepancy reignited debate on whether the Public Assistance Act should be amended to explicitly include permanent residents or other specific categories of foreign nationals, thereby providing them with clear legal rights and aligning the law with decades of practice and potentially with international human rights norms or constitutional principles regarding basic living standards.

- Constitutional Question Sidestepped: The Court confined its ruling to statutory interpretation and did not address the broader constitutional questions regarding whether excluding long-term foreign residents from the primary social safety net violates principles of equality (Art. 14) or the right to minimum standards of living (Art. 25).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 18, 2014, ruling definitively concluded that Japan's Public Assistance Act applies only to Japanese citizens and does not confer legally enforceable benefit rights upon foreign nationals, including those with permanent residency. While acknowledging the long-standing administrative practice of providing de facto assistance to certain foreigners based on a 1954 government notice, the Court held that this practice does not alter the statute's explicit limitation to "citizens." Foreigners remain recipients of administrative measures, not statutory entitlements under the Act. This decision clarifies the legal landscape but leaves open significant policy questions regarding the future legal status and security of social assistance for non-citizens residing in Japan.

- Japan Supreme Court on Public Assistance for Undocumented Foreign Residents (2001)

- Japan's Supreme Court Upholds Welfare Benefit Cut: The 2012 Old Age Addition Case

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Outline of the Public Assistance System – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare