Foreign Entity Classification for Tax: Japan's Supreme Court Rules on Delaware Limited Partnerships

Judgment Date: July 17, 2015

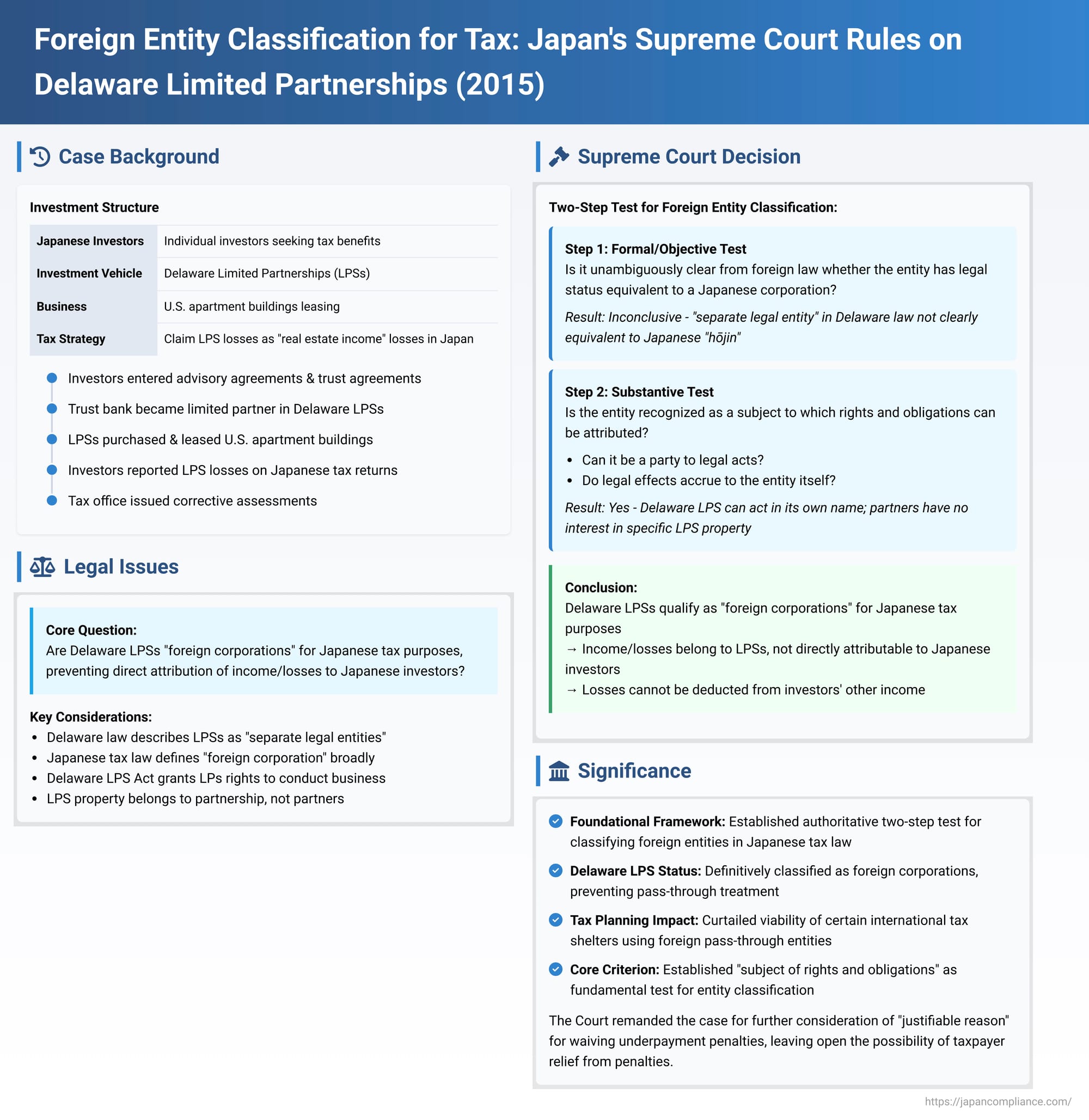

In a landmark decision with significant implications for Japanese investors in foreign entities and for international tax planning, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan established a crucial two-step framework for determining whether a foreign-organized entity should be treated as a "foreign corporation" for Japanese tax purposes. The case specifically involved U.S. Delaware Limited Partnerships (LPSs) used by Japanese individuals to invest in U.S. rental real estate. The Court concluded that these Delaware LPSs were indeed "foreign corporations," meaning their income and losses were not directly attributable to the Japanese investors for purposes of claiming deductions against other income in Japan.

The Investment Structure: Seeking Pass-Through Tax Benefits

The appellants, X (comprising individual investor X1 and the successors to two deceased investors, A and B, collectively referred to as "the Japanese investors"), had participated in an overseas real estate investment program. This program was structured as follows:

- Advisory and Trust Agreements: The Japanese investors entered into financial advisory agreements with "FS Advisory" (a securities firm) and established trust agreements with "T Bank," appointing T Bank as trustee and themselves as settlors and beneficiaries. They contributed cash to accounts at T Bank under these trusts.

- Formation of Delaware Limited Partnerships (LPSs):

- T Bank, acting as trustee, along with "Cayman Co." (a Cayman Islands-based entity), entered into Limited Partnership Agreements with Delaware Limited Liability Companies ("Delaware GP1" and "Delaware GP2") serving as General Partners.

- These agreements, governed by the Delaware Revised Uniform Limited Partnership Act ("Delaware LPS Act"), established two Delaware Limited Partnerships: "LPS One" (for investing in a U.S. apartment building, "Building 1") and "LPS Two" (for investing in another U.S. apartment building, "Building 2"). T Bank and Cayman Co. were Limited Partners in these LPSs.

- T Bank then contributed the cash from the Japanese investors' trusts into LPS One and LPS Two, thereby acquiring partnership interests in these entities on behalf of the trusts.

- Business Activity: LPS One and LPS Two purchased their respective U.S. apartment buildings and engaged in the business of leasing these properties to third parties ("the subject real estate leasing business").

- Intended Tax Treatment: The investment program was designed with the expectation that losses generated by the subject real estate leasing business (primarily due to depreciation expenses on the buildings) would "pass through" the LPSs and the trusts to the individual Japanese investors. The investors anticipated treating these losses as losses from "real estate income" (fudōsan shotoku - 不動産所得) on their Japanese income tax returns, which could then be offset against their other sources of income (a practice known as son'eki tsūsan - 損益通算, or profit and loss offsetting). This offsetting was expected to reduce their Japanese income tax and local inhabitant tax liabilities by an amount that could potentially exceed their initial investment.

The Tax Dispute and Lower Court Rulings

The Japanese investors (A, B, and X1) duly reported their share of the losses from the LPSs' leasing activities as real estate income losses on their Japanese income tax returns for the years in question (primarily 2001-2005). However, the relevant Japanese tax office issued corrective assessments and, where applicable, underpayment penalties. The tax office's position was that the income (or losses) generated by the leasing business did not constitute real estate income attributable to the Japanese investors and therefore could not be offset against their other income. This implied that the tax office did not view the Delaware LPSs as pass-through entities for Japanese tax purposes in this context.

The first instance court and the appellate High Court both ruled in favor of the Japanese investors (X). These lower courts effectively found that the Delaware LPSs were not "foreign corporations" under Japanese tax law (nor were they unincorporated associations with separate tax personality that would prevent pass-through). Consequently, they held that the income and losses from the real estate leasing business should be attributed directly to the investors and could be treated as real estate income (or loss) by them. The State, representing the tax office, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Framework for Classifying Foreign Entities

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions regarding the tax assessments (the portion concerning penalties was remanded). The central issue was the tax characterization of the Delaware LPSs.

I. The Core Question: Attribution of Income and Losses

The Court first framed the issue: when an organization composed of multiple investors conducts a business, the profits or losses from that business are, in the absence of special circumstances dictating otherwise, treated for tax purposes as belonging to the organization itself if it qualifies as a "corporation" under Japanese tax law. Conversely, if the organization does not qualify as a corporation, the profits or losses are attributed to its members.

"Therefore," the Court stated, "in judging the attribution of the said income in the present case, the question is whether the subject LPSs qualify as 'foreign corporations' as commonly defined in Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 7 of the Income Tax Act and Article 2, Item 4 of the Corporate Tax Act."

II. Defining "Foreign Corporation" for Japanese Tax Purposes

The Supreme Court then elaborated on how to determine if a foreign-established entity is a "foreign corporation":

- Purpose of the Definition: Japanese tax law defines a "foreign corporation" simply as "a corporation other than a domestic corporation." This broad definition acknowledges the diversity of corporate legislative policies in foreign countries. The intent is to identify and treat as foreign corporations those foreign-established entities that are equivalent in substance to Japanese domestic corporations and for which it is appropriate to impose tax liability separately from their members. The determination of whether an entity is a taxpayer as a corporation is a matter that defines the scope of Japan's taxing jurisdiction.

- The Most Essential Attribute of a Corporation in Japan: "In Japan, that an organization is a subject to which rights and obligations can be attributed (kenri gimu no kizoku shutai - 権利義務の帰属主体) is considered the most essential attribute of a corporation. Possessing such an attribute is thought to be the principal reason why, in Japanese tax law, a corporation is deemed capable of independently conducting business and is made a taxpayer separate from its members." Furthermore, the scope of who is considered a taxpayer must be determined by objective and clear criteria.

- The Two-Step Test: Based on these considerations, the Supreme Court established a two-step hierarchical test for determining if a foreign-established entity qualifies as a "foreign corporation" under Japanese tax law:

- Step 1: Formal/Objective Test (Clarity under Foreign Law):

"First, from the perspective of achieving a more objective and unambiguous determination, and considering the need for international legal harmony, one must examine whether, from the wording of the provisions of the entity's foreign enabling legislation and the structure of that foreign legal system, it is unambiguously clear that the entity is granted a legal status equivalent to a Japanese corporation, or, conversely, is unambiguously not granted such status."

If this inquiry yields an "unambiguously clear" answer, that determination (either it is, or is not, equivalent to a Japanese corporation) should be adopted for Japanese tax purposes. - Step 2: Substantive Test (Attribution of Rights and Obligations - if Step 1 is inconclusive):

"If [Step 1] is not possible (i.e., if foreign law is not unambiguously clear on its equivalence or non-equivalence to a Japanese corporation), then, next, from the perspective of the entity's attributes, one must examine and judge whether the said organization is recognized as a subject to which rights and obligations can be attributed. Specifically, based on the content and purpose of the entity's foreign enabling legislation, one must examine whether the organization can itself be a party to legal acts, and whether the legal effects of those acts accrue to the organization itself."

- Step 1: Formal/Objective Test (Clarity under Foreign Law):

III. Applying the Two-Step Test to the Delaware LPSs

The Supreme Court then applied this newly articulated two-step test to the Delaware LPSs in question:

(A) Step 1 Analysis (Clarity under Delaware Law):

The Court noted that Section 201(b) of the Delaware LPS Act states that a limited partnership formed under the Act "shall be a separate legal entity." However:

- It was "not clear whether 'legal entity' in Delaware law (including U.S. law generally) refers to a legal status equivalent to a 'corporation' (hōjin - 法人) under Japanese law."

- It was also "not clear whether an organization stated to be a 'separate legal entity' can be assessed as having a legal status equivalent to a Japanese corporation."

- The Court pointed out that the Delaware General Corporation Law uses the term "a body corporate" for corporations, not "separate legal entity."

Considering these points, the Supreme Court found it "difficult to conclude that it is unambiguously clear" from the Delaware LPS Act or related statutes whether the subject LPSs were granted a legal status equivalent to a Japanese corporation, or not. Thus, Step 1 was inconclusive.

(B) Step 2 Analysis (Subject of Rights and Obligations):

The Court then moved to the substantive test:

- Section 106(a) and (b) of the Delaware LPS Act provide that an LPS may carry on any lawful business, purpose, or activity (with certain exceptions, whether or not for profit) and possesses and may exercise all the powers and privileges granted by the Act, by any other law, or by its partnership agreement, together with any powers incidental thereto.

- The Supreme Court interpreted these provisions to mean that the Delaware LPS Act "grants a limited partnership the right or authority to perform legal acts in its own name, and presumes that the effects of legal acts done in the limited partnership's name accrue to the limited partnership itself."

- This interpretation was found to be consistent with Section 701 of the Delaware LPS Act, which states that a partnership interest is personal property and, crucially, "A partner has no interest in specific limited partnership property." This implies that the property of the LPS is owned by the LPS entity itself, not co-owned by the partners.

- The Court also examined the specific partnership agreements for LPS One and LPS Two. These agreements stated that the LPSs were formed for the purpose of purchasing, acquiring, developing, holding, leasing, managing, selling, or otherwise disposing of the subject buildings and their sites, and that they possessed the authority to do so. A clause in the agreements mentioning that partners held an "undivided interest" in the LPS property corresponding to their contribution ratio was interpreted by the Court as referring only to an abstract interest in the overall LPS property, not a concrete interest in specific assets. Thus, this clause did not contradict the Delaware LPS Act's provision that partners have no interest in specific LPS property.

Based on this analysis of the Delaware LPS Act and the specific partnership agreements, the Supreme Court concluded:

"The subject LPSs can themselves be parties to legal acts, and the legal effects of such acts accrue to the subject LPSs. Therefore, they are recognized as subjects to which rights and obligations can be attributed."

IV. Conclusion: Delaware LPSs are "Foreign Corporations"

Having found that the subject Delaware LPSs met the substantive test of being subjects of rights and obligations, the Supreme Court held:

"Consequently, the subject LPSs should be considered to qualify as 'foreign corporations' as defined in Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 7 of the Income Tax Act and related provisions."

Since the subject real estate leasing business was conducted by these LPSs (now deemed foreign corporations for Japanese tax purposes), and there were no special circumstances to suggest otherwise, the income and losses generated by this business belonged to the LPSs themselves. They were not included in the taxable income of the Japanese investors (X).

Therefore, the Japanese investors could not deduct the losses arising from the LPSs' real estate leasing business from their other personal income.

Judgment and Implications for Penalties

The Supreme Court found that the lower courts' judgments (which had allowed the loss deductions) were based on a clear error of law and therefore had to be reversed concerning the main tax assessments.

- The claims of X (the Japanese investors) for cancellation of the corrective tax assessments (which denied the loss offsets) and for cancellation of the notices of no reason for correction were dismissed. The tax office's position on the non-deductibility of the losses was upheld.

However, regarding the underpayment penalties, the Supreme Court noted that a separate issue arose: whether there was a "justifiable reason" (seitō na riyū) under Article 65, Paragraph 4 of the Act on General Rules for National Taxes that might warrant waiving these penalties. This could be relevant if, for example, the taxpayers had relied on a previous, different official interpretation by the tax authorities concerning the treatment of such LPS investments.

The Court decided that this aspect required further factual examination. Therefore, the part of the case concerning the cancellation of the underpayment penalty assessments was remanded to the Nagoya High Court for further proceedings specifically on the "justifiable reason" issue.

Significance of the Ruling

This 2015 Supreme Court decision is a landmark in Japanese international tax law:

- Establishes a Key Two-Step Test for Foreign Entity Classification: The judgment provides a foundational and structured analytical framework for determining whether any foreign-organized entity should be treated as a separate taxable corporation or as a pass-through entity for Japanese tax purposes. This test prioritizes clear indications from foreign law but falls back on a substance-based analysis centered on the Japanese legal concept of being a "subject of rights and obligations."

- Clarifies Status of Delaware LPSs: It specifically ruled that Delaware Limited Partnerships exhibiting the characteristics presented in this case are to be treated as foreign corporations by Japan. This has had a direct and significant impact on Japanese investments structured through such entities, generally precluding the direct pass-through of income or losses to individual Japanese investors for classification as specific income types like real estate income.

- Impact on International Tax Shelters: The decision significantly curbed the viability of certain types of international tax shelter strategies that relied on creating deductible losses for Japanese investors through foreign pass-through entities. By classifying such LPSs as corporations, the losses are contained within the foreign entity and cannot be readily used to offset Japanese domestic income.

- "Subject of Rights and Obligations" as a Core Criterion: The emphasis on whether an entity is a "subject to which rights and obligations can be attributed" provides a fundamental principle for analyzing various foreign entities in future cases. This test looks to whether the entity can act legally in its own name and whether legal consequences attach to the entity itself rather than directly to its members.

This ruling represents a major step by the Japanese Supreme Court in addressing the complexities of cross-border investments and the characterization of foreign legal entities within Japan's domestic tax system. It highlights a move towards ensuring that the Japanese tax treatment of foreign entities is based on a principled analysis that considers both international legal norms and core concepts of Japanese corporate and tax law.