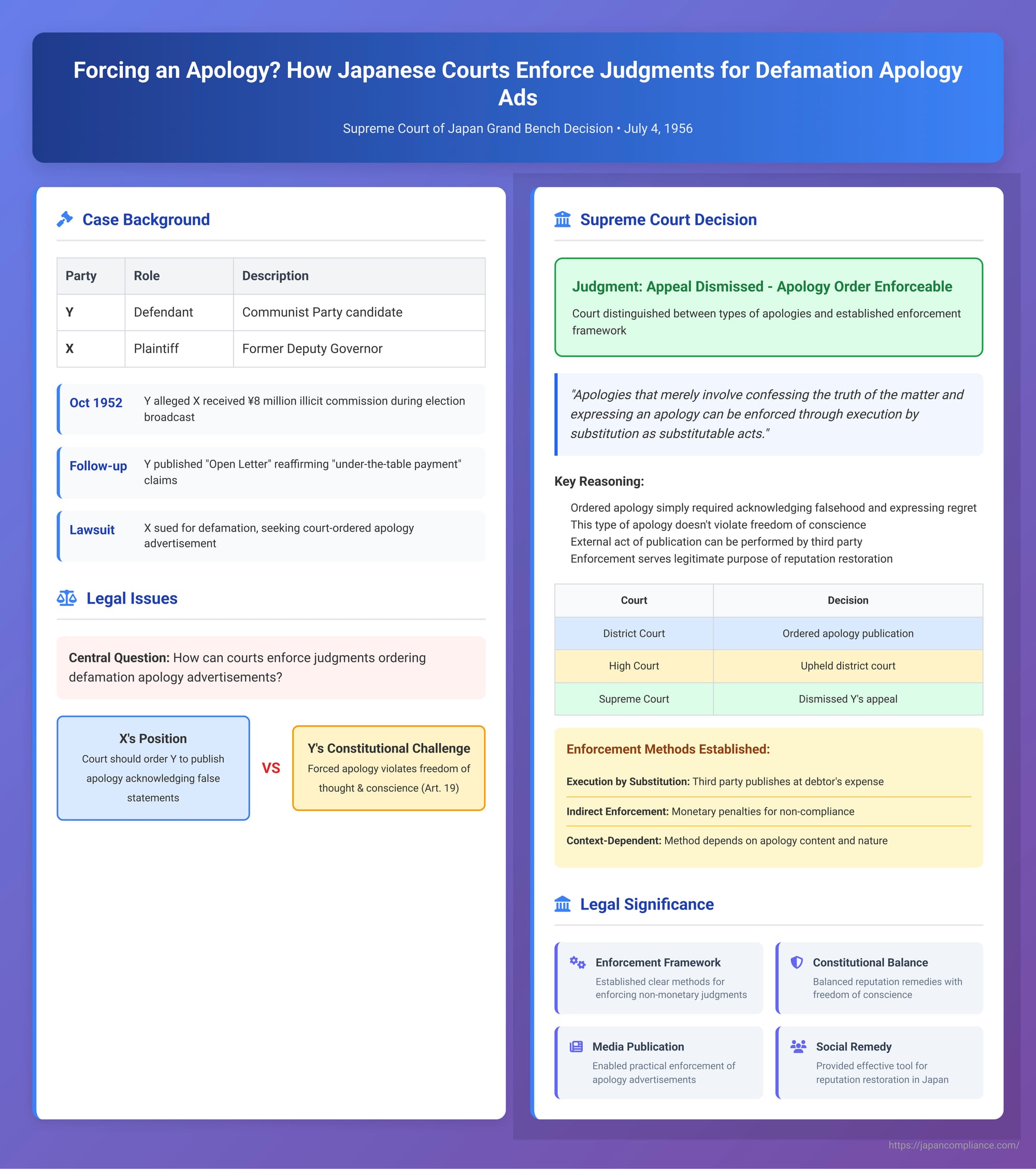

Forcing an Apology? How Japanese Courts Enforce Judgments for Defamation Apology Ads – Insights from a 1956 Supreme Court Case

Date of Judgment: July 4, 1956

Case Name: Apology Advertisement Claim Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Case Number: 1953 (O) No. 1241

Introduction

Defamation can cause significant harm to an individual's reputation. In Japan, beyond monetary damages, Article 723 of the Civil Code allows a court to order a person who has defamed another to take "suitable measures for restoring the victim's reputation." One of the most common and historically significant of these measures is a court-ordered "apology advertisement" (謝罪広告, shazai kōkoku), typically published in newspapers or other media.

But what happens if the defamer, ordered by a court to publish such an apology, refuses? How can such a judgment be enforced? This question becomes particularly acute when the defamer argues that being forced to apologize violates their freedom of thought and conscience, a right guaranteed by Article 19 of the Japanese Constitution. The Supreme Court of Japan confronted these complex issues, especially the methods of execution, in a landmark Grand Bench decision on July 4, 1956.

The Case of the Political Candidate and the Defamatory Broadcast

The case arose from statements made during a heated political campaign:

- Y (Defendant/Appellant): A candidate for the Japan Communist Party in the October 1952 House of Representatives general election in Tokushima Prefecture.

- X (Plaintiff/Respondent): The individual whose reputation was allegedly harmed.

During an election campaign broadcast, Y alleged that X, during X's tenure as Deputy Governor of Tokushima Prefecture, had illicitly received an 8 million yen commission related to the construction of a power plant. After a third party published a rebuttal to this claim in a local newspaper, Y doubled down, publishing an "Open Letter" in the same newspaper. In this letter, Y asserted that the "fact" that X had received an 8 million yen "under-the-table payment" (そでの下, sode no shita) could not be denied.

X sued Y, seeking the restoration of X's honor. Specifically, X demanded that Y be ordered to publish a letter of apology in designated newspapers and to have the same apology broadcast by media companies.

The lower courts sided with X:

- The First Instance Court (Tokushima District Court) ordered Y to publish an apology in newspapers. The court-specified text included the statement: "The said broadcast and article were contrary to the truth, damaged your honor, and caused you trouble. I hereby express my apologies."

- The Second Instance Court (Takamatsu High Court) upheld this judgment.

Y appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that the statements made were true and in the public interest. Crucially, Y contended that forcing Y to publish an apology containing content Y did not personally agree with or intend would violate Y's freedom of thought and conscience under Article 19 of the Constitution. This constitutional challenge brought the method and legitimacy of enforcing apology advertisements to the forefront.

The Supreme Court's 1956 Grand Bench Ruling: Enforcing Apologies

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench, by a majority, dismissed Y's appeal. While the case is famous for its constitutional debate, the Court also made significant pronouncements on how judgments ordering apology advertisements should be enforced. This is the focus of our analysis, drawing from the PDF commentary.

The majority opinion reasoned as follows regarding the execution method:

- Accepted Remedy: Ordering a defamer to publish an apology advertisement in newspapers or other media as a "suitable measure for restoring reputation" under Civil Code Article 723 was already an established practice, accepted by both legal scholars and prior case law. Such advertisements were also a feature of Japanese social practice.

- Nature of the Obligation and Enforcement Method Can Vary: The Court acknowledged that the enforceability and method of enforcement could depend on the content of the ordered apology:

- Non-Substitutable Acts (Indirect Enforcement): Some apology judgments, due to their specific required content, might be such that their publication is appropriately left to the defamer's personal decision. Enforcing these would fall under the category of "non-substitutable acts" (不代替作為, fudaitai sakui), where performance depends solely on the debtor's will. For such obligations, indirect enforcement (間接強制, kansetsu kyōsei) – compelling performance by imposing monetary penalties for non-compliance (under then-Code of Civil Procedure Art. 734, now Civil Execution Act Art. 172) – would be the appropriate method.

- Unenforceable Apologies: The Court also conceded that, at times, compelling an apology could "ignore the debtor's personality, significantly damage their honor, and unjustly restrict their freedom of decision-making or conscience," rendering it unsuitable for any form of compulsory execution.

- Substitutable Acts (Execution by Substitution): However, the Court carved out a significant category. For apologies that "merely involve confessing the truth of the matter and expressing an apology (陳謝の意を表明するに止まる程度)", their compulsory execution can be achieved through the procedure for "execution by substitution" (代替執行, daitai shikkō) as a "substitutable act" (代替作為, daitai sakui) (under then-Code of Civil Procedure Art. 733, now Civil Execution Act Art. 171).

- Application to the Present Case: The apology demanded by X and ordered by the lower courts required Y to state, under Y's name and addressed to X, regarding the specified broadcast and newspaper article: "The said broadcast and article were contrary to the truth, damaged your honor, and caused you trouble. I hereby express my apologies." The Supreme Court interpreted this as essentially requiring Y to announce through mass media that Y's previously published statements were false and improper.

- No Violation of Conscience for This Type of Apology: The Court concluded that ordering the publication of this particular type of apology did not impose humiliating or servile labor on Y, nor did it compel Y to violate Y's ethical will or freedom of conscience. It was also deemed a "suitable measure" under Civil Code Art. 723.

Therefore, the judgment for this apology could be enforced.

Execution Methods for Apology Advertisements Explained

The 1956 Supreme Court decision, by distinguishing between types of apologies, implicitly guided the choice of execution methods. The PDF commentary elaborates on these:

1. Execution by Substitution (代替執行, Daitai Shikkō) - The Primary Method

- Prevailing View: The dominant legal view in Japan, both historically (held by Civil Code drafters like Ume Kenjiro and the pre-war Daishin-in) and currently, is that the obligation to publish a standard apology advertisement is a substitutable act. This means the act can, in theory, be performed by someone other than the debtor (defamer) at the debtor's expense.

- Rationale: This classification focuses on the external act of getting the advertisement published, rather than the internal sincerity of the apology. The reasoning is:

- If a court has ordered an advertisement with specific content, a newspaper company will typically agree to publish it if a contract is made and paid for. The core obligation is fulfilled once the ad appears.

- The contract to publish the advertisement doesn't necessarily have to be entered into by the defamer themself; a third party can do it on their behalf, with the defamer bearing the cost.

- The economic and legal effect of the publication is the same regardless of who makes the arrangements with the publisher.

- The Process (under current Civil Execution Act Art. 171):

- Application for Authorization: The creditor (the defamed party, X) applies to the court of first instance (which acts as the execution court) for an "authorization decision" (授権決定, juken kettei). This application is based on the final, enforceable judgment ordering the apology.

- Debtor Hearing: The execution court must summon the debtor (defamer, Y) for a hearing before issuing the authorization.

- Authorization Decision: If the court grants the application, it issues a decision. This decision authorizes the creditor (or a third party designated by the creditor) to perform the act of contracting with the newspaper (or other media outlet) for the publication of the specified apology, at the debtor's expense. The court can also order the debtor to prepay these anticipated costs.

- Specificity: The authorization decision must clearly define the scope of the authorized act. In practice, the original judgment ordering the apology usually specifies the exact text of the apology, font, size, placement, the newspaper(s) or media, etc. The authorization decision typically incorporates these details.

- Execution of Authorization: The creditor then uses this authorization to enter into a contract with the newspaper for the advertisement's publication.

- A Key Limitation: The newspaper or media outlet is a third party and is not itself under any obligation to publish the apology merely because of the court's authorization to the creditor. If the newspaper refuses to accept the advertisement (e.g., due to its own editorial policies or other reasons), execution by substitution becomes impossible. In such a scenario, the creditor might then have to consider indirect enforcement.

2. Indirect Enforcement (間接強制, Kansetsu Kyōsei)

- When Indirect Enforcement is Primary: The 1956 Supreme Court judgment acknowledged that some apology obligations, by their nature, might be non-substitutable acts performable only by the debtor. For these, indirect enforcement (Civil Execution Act Art. 172), which involves the court ordering the debtor to pay a monetary penalty for each day of non-compliance to coerce performance, would be the appropriate method.

- The PDF commentary suggests examples such as when a debtor is ordered to publish an apology using media outlets under their own control (e.g., their personal blog, company website, or a publication they own). Posting an apology on a physical bulletin board managed by the debtor would also fall into this category. In these cases, a third party cannot easily perform the act for the debtor.

- Indirect Enforcement as an Alternative for Substitutable Acts (Current Law): A significant development in Japanese execution law (Civil Execution Act Art. 173(1)) is that for obligations that are substitutable (like publishing an apology in a third-party newspaper), the creditor now has the option to choose indirect enforcement instead of execution by substitution. The previous rule, where indirect enforcement was generally "supplementary" (available only if direct or substitutable execution failed or was inappropriate), has been abolished.

- Theoretical Implications: This modern option for creditors to choose indirect enforcement even for standard apology ads leads the PDF commentary to question whether the 1956 Supreme Court's fundamental premise – that execution by substitution for fact-confessing, apology-expressing ads does not violate freedom of conscience – might need re-evaluation. If the state can now use monetary coercion (indirect enforcement) to achieve the publication of the same apology, the nature of the "compulsion" might be seen differently. However, the commentary also notes that, practically speaking, indirect enforcement is unlikely to be a more rapid or efficient method than execution by substitution for typical newspaper apology ads, making this more of a theoretical concern than a common practical choice.

The Content of the Apology in the 1956 Case

The Supreme Court found that the specific apology ordered in Y's case – acknowledging that the statements were "contrary to the truth," had "damaged your honor," and "caused you trouble," and concluding with "I hereby express my apologies" – was of a type that "merely involve[d] confessing the truth of the matter and expressing an apology." As such, it did not, in the majority's view, impose an unconstitutional burden on Y's conscience and was suitable for enforcement, primarily through execution by substitution.

Conclusion: A Framework for Enforcing Non-Monetary Judgments

The 1956 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision, while deeply engaged with the constitutional protection of conscience, also laid down a crucial framework for understanding how non-monetary judgments, specifically orders for apology advertisements, are to be enforced in Japan. It established that "standard" apologies, focused on factual correction and a formal expression of regret, could be treated as substitutable acts, primarily enforceable through execution by substitution. This allows the legal system to provide a tangible remedy for reputational harm.

While the Court acknowledged that highly personal or conscience-infringing apologies might be unsuitable for any enforcement, or suitable only for indirect enforcement, its core holding paved the way for the practical realization of apology orders. The subsequent evolution of the Civil Execution Act, particularly the expanded availability of indirect enforcement, adds another layer to the options available to creditors, though the practical efficacy for standard apology ads likely still favors execution by substitution when media cooperation is forthcoming. This landmark case continues to inform the delicate balance between redressing reputational damage and respecting individual freedoms in the enforcement of justice.