Forced to the Brink: When Does Coercing a Suicide Become Murder in Japan?

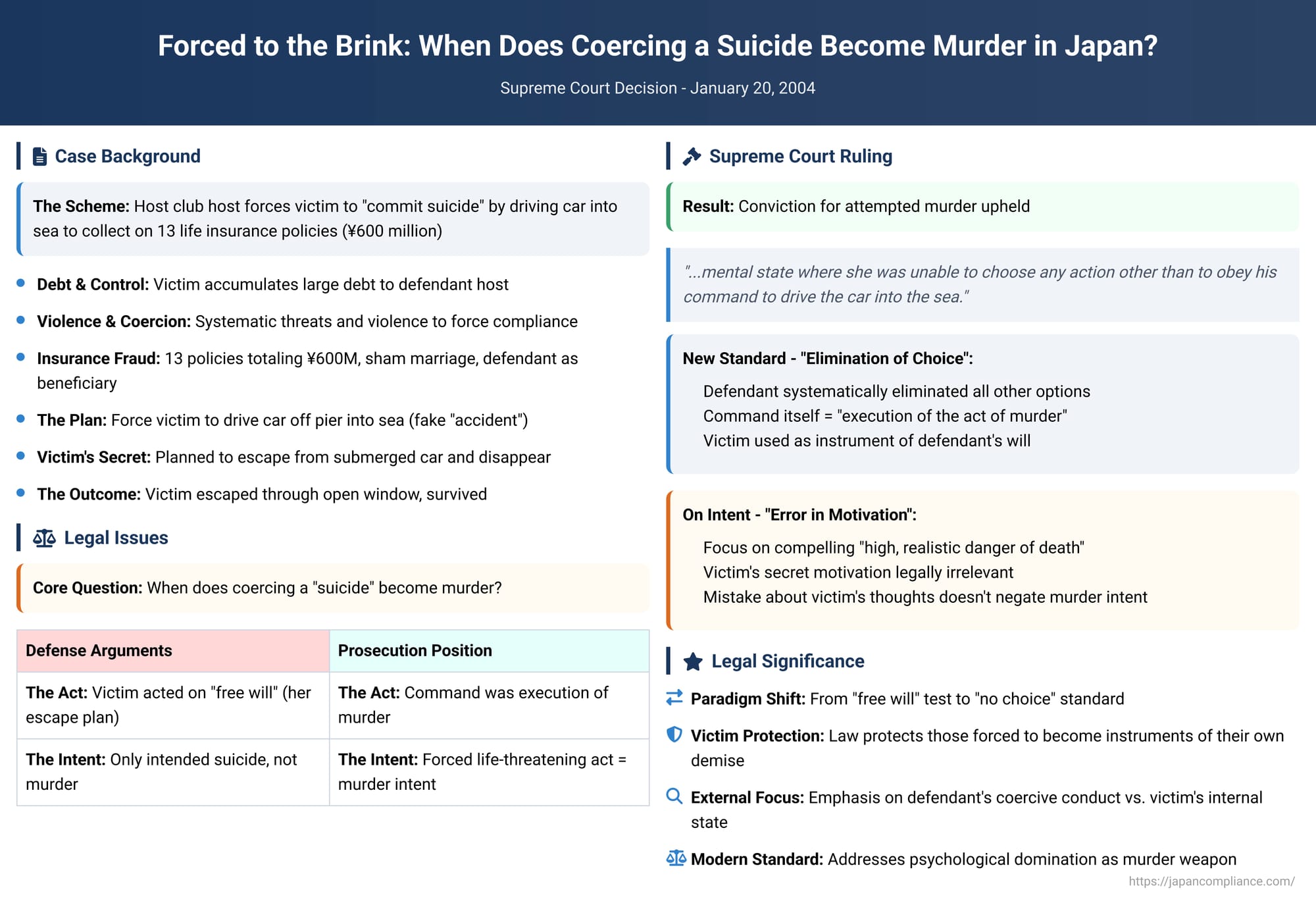

Can you murder someone by forcing them to kill themselves? Where does the law draw the line between illegally inducing a suicide and committing the crime of murder itself? This dark and complex question was the subject of a major decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on January 20, 2004. In a case involving a manipulative "host club" host who drove his victim to the brink, the Court clarified the standard for when extreme coercion transforms into the execution of murder, focusing not on the victim's internal will to die, but on the defendant's power to eliminate all other choices.

The Facts: A Web of Control and Deceit

The case details a harrowing story of manipulation and control. The defendant, a host at a nightclub, had a female customer, the victim, who had amassed a large debt to him. To ensure payment, he subjected her to a campaign of intense violence and threats, forcing her into a state of extreme fear and submission. He compelled her to work in the sex industry, taking her earnings to pay down the debt.

Eventually, the defendant devised a more sinister plan. He conspired to have the victim killed in order to collect on massive life insurance policies. He had her take out 13 policies totaling nearly 600 million yen, entered into a sham marriage with her, and designated himself as the beneficiary. His plan was to force her to commit "suicide" in a way that would appear to be an accidental death, which would trigger a larger disaster-related insurance payout. The chosen method: she would drive a car off a pier into the sea.

For two days prior to the event, the defendant relentlessly pressured the victim, using physical violence and threats to force her to go through with the plan. He drove her to the location, demonstrated how to drive off the edge, and when she begged for a reprieve, made her promise to carry it out the following day.

However, the victim had a secret. She did not want to die. Terrified of the defendant, she considered killing him to save herself but ultimately decided against it. Instead, she concocted a desperate plan for her own survival: she would follow his orders to drive the car into the sea, but she would attempt to escape from the submerged vehicle and then disappear, faking her death to finally be free of him.

On the night of the crime, the defendant took the victim to the fishing port. He ordered her into the driver's seat and instructed her to lock the doors, close the windows, and fasten her seatbelt—all measures designed to make escape nearly impossible. He then commanded her to drive off the pier. To prevent her from pleading for her life again, he drove away to a spot where he could monitor her actions from a distance.

Shortly after he left, the victim put her plan into action. Contrary to his instructions, she left her seatbelt unfastened and her driver's side window open. She then drove the car off the pier and into the frigid January sea. Before the vehicle fully submerged, she successfully escaped through the open window and swam to a nearby fishing boat, saving her own life.

The Legal Question: Murder, or Suicide by Command?

The defendant was charged with attempted murder. His defense rested on two key arguments regarding the victim's state of mind:

- The Act: He argued that his command to drive into the sea was not the "execution of murder" because the victim ultimately acted on her own free will—her personal decision and plan to escape.

- The Intent: He claimed that his intent was only to make her commit suicide. Since she never actually had the will to die, his intent for murder (killing another person) was not present.

This created a fascinating legal dilemma. If the victim's final action was driven by a will to live, could the defendant who forced her into that action be a murderer?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Compelling a Dangerous Act is Murder

The Supreme Court rejected the defense's arguments and upheld the conviction for attempted murder. In its ruling, the Court established a clear and powerful standard for this type of "indirect" killing.

The New Standard for Execution: Eliminating Choice

The Court's decision pivoted away from a nebulous inquiry into the victim's "free will." Instead, it focused on the overwhelming coercive power exerted by the defendant. The Court found that due to the preceding violence and threats, the defendant had forced the victim into a:

"...mental state where she was unable to choose any action other than to obey his command to drive the car into the sea."

Because he had systematically eliminated all other options, his command was not a suggestion; it was the direct cause of the life-threatening act. The Court ruled that when the defendant ordered the victim, who was in this state of duress, to drive into the sea, his command itself constituted the "execution of the act of murder." He was, in effect, using the victim's body as the instrument to carry out his own will.

The Ruling on Intent: An Error in Motivation

The Court then addressed the defendant's second argument—that he couldn't be guilty of murder because the victim never truly intended to die. The Court dismissed this as legally irrelevant.

It reasoned that the defendant's criminal intent was focused on compelling the victim to perform an act with a "high, realistic danger of death." He knew driving a car into the frigid sea was extraordinarily dangerous and likely fatal. His purpose was to force that specific, life-threatening act.

The victim's secret, internal motivation (to escape rather than to die) was a fact unknown to the defendant, but it did not change the nature of what he was forcing her to do. The Court effectively treated this as a non-essential "error in attribution." The defendant's mistake was about the victim's internal thoughts, not about the objective reality of the deadly act he was forcing upon her. The Court concluded this mistake "is not a circumstance that should negate the defendant's intent for the crime of murder."

The Broader Implication: From "Free Will" to "No Choice"

This 2004 decision represents a significant evolution in Japanese law. Earlier cases often struggled with the abstract concept of whether a victim's "free will" had been completely negated. This case provided a more practical and just standard by shifting the focus from the victim's internal state to the defendant's external actions.

The key question is no longer "Did the victim retain free will?" but rather, "Did the defendant's coercive conduct eliminate all other reasonable courses of action for the victim?" If a person, through violence, threats, and manipulation, creates an environment of such total domination that the victim is forced to undertake a life-threatening act, the perpetrator is a murderer. The law will hold the abuser responsible for the choices they steal, not just the actions they command.

Conclusion

The 2004 Supreme Court decision provides a crucial modern understanding of how murder can be committed not just with a weapon, but with the force of psychological domination. It clarifies that a person can be found guilty of murder for compelling another to perform a suicidal act when the coercion is so extreme that it leaves the victim with no other viable path. By focusing on the elimination of choice rather than the negation of will, the Court ensured that the law can protect victims who are forced to become the instruments of their own demise, recognizing that even a desperate act of self-preservation does not absolve the one who created the need for it.