Forced Labor Regulations and Global Supply Chains: Japan's Position and Implications

TL;DR

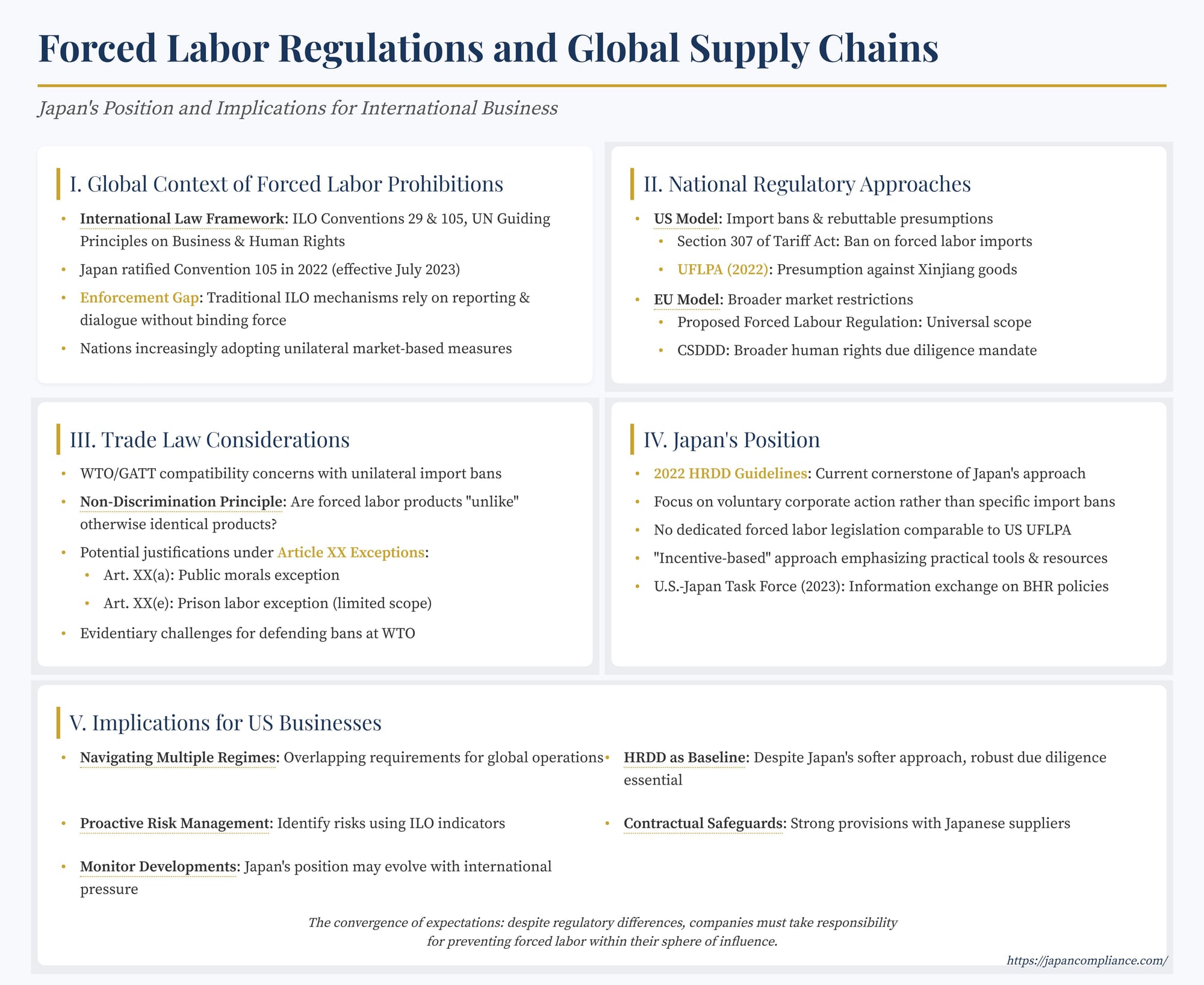

- The U.S. (UFLPA), EU, and several national laws are tightening forced-labor bans that block or withdraw products from their markets.

- WTO rules may permit such bans under the public-morals exception, but legality is still largely untested.

- Japan currently relies on soft-law HRDD Guidelines instead of import bans, focusing on voluntary due diligence.

- U.S. businesses sourcing in or through Japan must still map supply chains to raw-material level to meet UFLPA and impending EU rules.

- Contractual clauses, proactive audits, and continuous HRDD remain critical for avoiding shipment detentions and reputational harm.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Global Crackdown on Forced Labor

- The International Prohibition and Enforcement Challenges

- National Regulatory Approaches to Combating Forced Labor

- Trade Law Considerations: WTO/GATT Compatibility

- Japan's Current Position

- Implications for US Businesses

- Conclusion: The Imperative of Comprehensive Due Diligence

Introduction: The Global Crackdown on Forced Labor

The fight against forced labor in global supply chains has rapidly escalated into a major compliance and ethical imperative for international businesses. Defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO) as "all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily," forced labor represents a severe violation of fundamental human rights. High-profile reports, advocacy campaigns, and increased regulatory scrutiny have brought the issue to the forefront, demanding action from both governments and corporations.

Governments, particularly in North America and Europe, are increasingly moving beyond voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives and implementing mandatory measures. These range from disclosure requirements and comprehensive human rights due diligence (HRDD) mandates to targeted import controls aimed at blocking goods produced with forced labor from entering their markets. This evolving regulatory landscape presents significant challenges for multinational corporations managing complex, cross-border supply chains.

While Japan has recently introduced its own HRDD guidelines, its approach currently differs from the more punitive, trade-focused measures seen elsewhere. This article examines the key international regulatory trends concerning forced labor, analyzes Japan's current position within this global context, and explores the implications for US businesses operating in or sourcing from Japan.

The International Prohibition and Enforcement Challenges

The prohibition of forced labor is firmly established in international law. Key ILO instruments, including the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29) and the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105), are considered fundamental conventions, meaning member states have an obligation to respect, promote, and realize their principles, regardless of formal ratification status (though Japan ratified No. 105 in 2022, effective July 2023). The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights also explicitly include freedom from forced labor as a core right companies must respect.

Despite this clear international consensus, enforcement remains a challenge within the decentralized international legal system. Traditional ILO supervisory mechanisms rely primarily on reporting, dialogue, and recommendations, which lack binding legal force on sovereign states. While the ILO constitution allows for measures against member states persistently violating conventions (as seen exceptionally with Myanmar), these are rare. Similarly, UN Special Rapporteurs can investigate and report on situations like alleged forced labor (e.g., in China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region - XUAR), but their findings do not automatically trigger legal sanctions.

This enforcement gap has led individual states and regional blocs to adopt unilateral measures – leveraging their market power through domestic regulations to influence conditions beyond their borders.

National Regulatory Approaches to Combating Forced Labor

Several distinct models for tackling forced labor through national regulation have emerged:

1. The US Model: Import Bans and Rebuttable Presumptions

The United States employs a trade-based approach centered on prohibiting the importation of goods made with forced labor.

- Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930: This long-standing provision bans imports produced wholly or in part by convict, forced, or indentured labor. Its enforcement was historically limited by a "consumptive demand" exception (allowing imports if domestic production was insufficient), but Congress repealed this exception in 2015, paving the way for more robust application. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) can issue Withhold Release Orders (WROs) based on reasonable suspicion, detaining goods until the importer proves they were not made with forced labor.

- The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) (Effective June 2022): This landmark legislation specifically targets concerns about forced labor in the XUAR. It establishes a rebuttable presumption that any goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in the XUAR, or by entities designated on the UFLPA Entity List, are made with forced labor and therefore barred from importation under Section 307.

- Burden Shift: The UFLPA shifts the burden of proof squarely onto the importer, who must provide "clear and convincing evidence" that the goods were not made with forced labor to overcome the presumption. This is an extremely high standard, and to date, CBP has reported very few, if any, successful rebuttals leading to exceptions being granted.

- Scope and Enforcement: The UFLPA applies regardless of the value of the input from the XUAR or listed entity (no de minimis exception). CBP enforcement has been active, resulting in significant numbers of detained shipments across various sectors (electronics, apparel, solar panels, automotive, and increasingly, aluminum, seafood, and PVC following their designation as high-priority sectors). Enforcement relies on supply chain tracing, risk assessments, and increasingly sophisticated tools like isotopic testing.

The US approach effectively mandates deep supply chain due diligence for companies importing into the US, forcing them to map their supply chains back to the raw material level to ensure no connection to the XUAR or listed entities, or risk detention of their goods.

2. The EU Model: Proposed Regulation and Existing Tools

The European Union is finalizing its own dedicated instrument to combat forced labor, complementing its broader Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

- Proposed EU Forced Labour Regulation: In September 2022, the European Commission proposed a regulation prohibiting the placing and making available on the EU market of products made with forced labor, as well as the export of such products. Key features include:

- Universal Scope: Unlike the UFLPA's initial regional focus, the proposed EU ban applies to products regardless of geographic origin (including domestically produced goods) or sector.

- Risk-Based Enforcement: National authorities would investigate based on substantiated concerns submitted by third parties or on their own initiative, employing a risk-based approach.

- Investigation and Decision: Authorities would request information from companies, conduct checks, and potentially carry out inspections (including outside the EU with government/company consent). If forced labor is confirmed, authorities would order the withdrawal of the product from the EU market and prohibit its placement or export. Companies would be required to dispose of the goods. Non-compliance could lead to penalties under national law.

- Burden of Proof: While companies are expected to cooperate, the initial burden rests on the authorities to establish the use of forced labor based on available evidence. However, if a company fails to provide required information during an investigation in high-risk areas, decisions might be made based on "best facts available."

- Status: The European Parliament and Council reached a provisional agreement on the regulation in March 2024. Final adoption and publication are pending, after which member states will have time to implement it.

- Existing EU Tools: The EU also utilizes other mechanisms:

- GSP Conditionality: The EU's Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP), offering trade benefits to developing countries, includes conditionality based on the implementation of core human rights and labor conventions, including those on forced labor. Preferences can be withdrawn for "serious and systematic violations," as has occurred previously with countries like Myanmar and Cambodia (partially).

- CSDDD: While not solely focused on forced labor, the CSDDD will require large EU and non-EU companies meeting certain turnover thresholds within the EU to conduct mandatory HRDD, including identifying, preventing, and mitigating forced labor risks in their value chains.

The EU approach combines a potential market-wide import ban with broader due diligence obligations and existing trade preference leverage.

3. Other National Laws: Several individual countries, particularly in Europe (e.g., Germany's Supply Chain Act, France's Duty of Vigilance Law, the Netherlands' Child Labour Due Diligence Law), have enacted legislation requiring companies to conduct varying degrees of HRDD, often including specific attention to forced labor risks.

Trade Law Considerations: WTO/GATT Compatibility

A significant legal question surrounding unilateral import bans based on how goods are produced (Process and Production Methods - PPMs), such as those made with forced labor, is their compatibility with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, primarily the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).

- Non-Discrimination Principle: GATT generally requires member states to treat "like products" from all other member states equally (Most-Favored Nation - MFN, Article I) and to treat imported products no less favorably than domestically produced "like products" (National Treatment, Article III). The key issue is whether products made with forced labor are "unlike" otherwise identical products made under acceptable conditions. Traditionally, WTO jurisprudence has focused on the physical characteristics of the product itself, not the production method, making it difficult to differentiate based on non-product-related PPMs (NPR-PPMs) like labor conditions.

- General Exceptions (Article XX): Even if a measure violates core GATT principles, it might be justifiable under Article XX exceptions, provided it is not applied in a manner constituting arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade. Relevant exceptions could include:

- Article XX(a) - Public Morals: A country might argue that banning forced labor products is necessary to protect its public morals. Defining "public morals" is left to each member, but the measure must still meet a necessity test, balancing the importance of the objective, the measure's contribution to it, and its trade restrictiveness. Alternative, less trade-restrictive measures must be considered. The EC-Seals case, which upheld an EU ban on seal products harvested inhumanely, provides some precedent for using the public morals exception for process-related concerns, though human rights specifically haven't been tested in this context at the WTO.

- Article XX(e) - Prison Labor: This explicitly allows measures relating to the products of prison labor, but its applicability to broader state-imposed forced labor is debatable.

- Challenges: Defending a forced labor import ban at the WTO could be challenging. The country imposing the ban would need to demonstrate the measure is necessary, does not arbitrarily discriminate between countries where similar conditions prevail, and is not simply protectionism in disguise. Proving the existence of forced labor in a specific supply chain without access or cooperation from the exporting country also presents evidentiary hurdles. To date, measures like the UFLPA have not been formally challenged at the WTO.

Japan's Current Position

Japan's approach to combating forced labor in supply chains currently relies primarily on guidance and promoting voluntary corporate action, rather than specific import bans or mandatory due diligence statutes.

- The 2022 HRDD Guidelines: As discussed previously, these guidelines are the cornerstone of Japan's BHR policy. They strongly encourage companies to conduct HRDD, explicitly referencing international standards that prohibit forced labor. Companies following the guidelines should be identifying and addressing forced labor risks within their value chains as part of this process.

- Lack of Specific Legislation: Unlike the US or the proposed EU regulation, Japan currently has no law specifically banning the import of goods made with forced labor, nor does it mandate HRDD through statute. While there has been some discussion and advocacy from civil society groups for Japan to adopt measures similar to the UFLPA or the EU proposal, no concrete legislative proposals have gained significant traction within the government as of early 2025.

- Government Emphasis: The Japanese government, particularly METI, has focused on providing practical tools, resources, and best practice examples to help companies, including SMEs, understand and implement the HRDD Guidelines. This reflects a preference for an "incentive-based" or supportive approach over a purely "sanction-based" one.

- International Cooperation: Japan actively participates in international fora discussing BHR and supply chain issues. Notably, it co-established the "U.S.-Japan Task Force on the Promotion of Human Rights and International Labor Standards in Supply Chains" with the United States in 2023. This task force facilitates information exchange on laws, policies, and best practices between the two governments and engages with stakeholders (businesses, civil society, labor organizations) to promote responsible business conduct, including due diligence to combat forced labor.

In essence, Japan expects companies to address forced labor risks as part of their overall HRDD commitments under the 2022 Guidelines, but it does not currently use trade restrictions or specific legal mandates as primary enforcement tools for this issue.

Implications for US Businesses

The complex and fragmented global regulatory landscape regarding forced labor has several implications for US businesses with ties to Japan:

- Navigating Multiple Regimes: Companies operating globally may face overlapping, and sometimes differing, requirements. A US company importing goods into the US that transit through or involve suppliers in Japan must comply with UFLPA. If that company also operates in the EU, it will need to prepare for the EU Forced Labour Regulation and potentially the CSDDD. Simultaneously, its operations and relationships within Japan are subject to the expectations set by the Japanese HRDD Guidelines. Compliance requires a sophisticated understanding of each regime.

- HRDD as a Baseline: Regardless of Japan's specific legal framework, robust HRDD is essential. US laws like the UFLPA effectively require deep supply chain visibility. Identifying and mitigating forced labor risks within Japanese portions of the supply chain is crucial not only to meet the expectations of the Japanese Guidelines but also to ensure compliance with potentially stricter US or EU regulations applicable to the company's broader operations or market access.

- Proactive Risk Management: Relying solely on the absence of a Japanese import ban is risky. The global trend is towards increased scrutiny and mandatory measures. Companies should proactively assess their Japanese supply chains for forced labor risks, using tools like the ILO's indicators of forced labor (e.g., abuse of vulnerability, deception, restriction of movement, isolation, physical/sexual violence, intimidation, retention of identity documents, withholding of wages, debt bondage, abusive working/living conditions, excessive overtime).

- Contractual Safeguards: While Japanese law may not mandate specific clauses, incorporating strong contractual provisions related to forced labor prohibition, audit rights, and remediation requirements in contracts with Japanese suppliers is a prudent risk mitigation strategy, aligning with the principles discussed in the previous article on contractual liabilities.

- Monitoring Japanese Developments: Although currently focused on guidance, the Japanese government's position could evolve, potentially influenced by international pressure or developments within the US-Japan Task Force. Businesses should monitor any legislative or policy shifts in Japan regarding forced labor or mandatory HRDD.

Conclusion: The Imperative of Comprehensive Due Diligence

The global momentum to eradicate forced labor from supply chains is undeniable. While regulatory approaches differ—with the US employing targeted import bans based on rebuttable presumptions, the EU moving towards a market-wide prohibition, and Japan currently emphasizing guidelines-based HRDD—the underlying expectation for businesses is converging: companies must take responsibility for preventing forced labor within their sphere of influence.

For US businesses interacting with Japan, this means that compliance with US regulations like the UFLPA necessitates scrutiny extending into their Japanese supply chain links. Furthermore, adherence to Japan's 2022 HRDD Guidelines requires a proactive approach to identifying and mitigating forced labor risks as part of a broader human rights commitment. While Japan's "soft law" approach may seem less demanding than US or EU "hard law," the practical consequences of inaction—driven by investor pressure, consumer awareness, and the requirements of international business partners—are significant. A comprehensive, risk-based HRDD process, informed by international standards and tailored to the specific operational context, is the most effective strategy for navigating this complex and evolving regulatory environment.

- Human Rights in Japanese Supply Chains: Contractual Strategies and Legal Liabilities

- Integrating Human-Rights Due Diligence into Japanese Supply Chains

- Beyond Borders: Germany’s Supply-Chain Act & Mandatory Human-Rights Due Diligence

- METI | “Task Force on Promotion of Human Rights and International Labour Standards in Supply Chains”

https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2023/0502_001.html - MOFA | “Japan’s Support for Responsible Business Conduct and Human Rights Due Diligence”

https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/business_foresight/human_rights.html