Following the Money: Unjust Enrichment When Stolen Funds Are Used to Pay Debts – A Japanese Supreme Court View

Date of Judgment: September 26, 1974

Case Name: Claim for Return of Monetary Sum

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

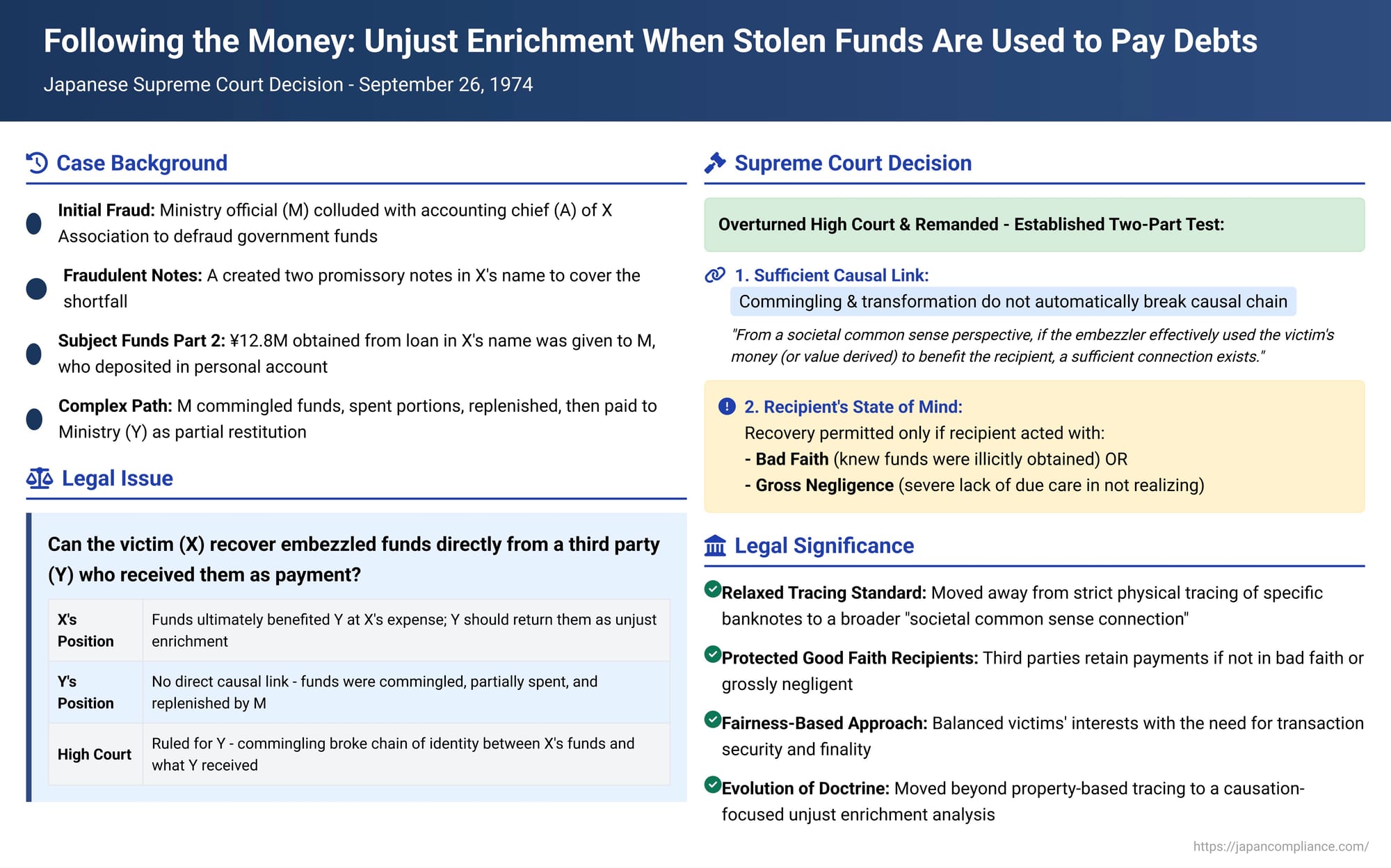

It's an unfortunate reality of commerce and life: funds are sometimes lost through fraud or embezzlement. When the wrongdoer then uses these misappropriated monies to pay off their own debts or obligations to a third party, a difficult legal question arises. Can the original victim from whom the funds were stolen recover them directly from the third party who ultimately received them? Or does the third-party recipient, especially if they were unaware of the money's illicit origins, get to keep the payment? A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision from September 26, 1974, established a crucial framework for addressing these "payment with embezzled funds" scenarios under the law of unjust enrichment.

A Bureaucrat, A Colluding Manager, and Misappropriated Funds: The Intricate Facts

The case stemmed from a significant fraud involving government subsidies:

- The Initial Fraud: M, an official at Japan's Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, colluded with A, the accounting section chief of X (the Ibaraki Prefecture Agricultural Mutual Aid Association Federation – an agricultural cooperative). Together, they devised a scheme to defraud government funds that were supposed to be disbursed as subsidies to various agricultural associations, including X.

- The Cover-Up and Misuse of X's Credit: To conceal the shortfalls created by their fraud, M enlisted A's further help. A, abusing his position at X, improperly created two promissory notes in X's name.

- Subject Funds Part 1: Using one of these fraudulent promissory notes, A borrowed approximately ¥19.46 million from a bank, ostensibly in X's name. (X was later held liable for this loan due to principles of apparent authority). A then obtained a cashier's check for most of this sum (approx. ¥19.35 million) and, at M's direction, delivered it to M's unsuspecting superior at the Ministry. This payment was disguised as X returning previously overpaid subsidies. These funds were then used by the Ministry to correctly pay subsidies owed to the Saitama Prefecture agricultural association, effectively plugging one hole created by M's fraud.

- Subject Funds Part 2: Using the second fraudulent promissory note, A similarly borrowed another ¥15 million in X's name. From these funds, A obtained a cashier's check for ¥12,806,434 and handed it to M.

- Commingling and Restitution Journey of Subject Funds Part 2:

- M initially intended to use Subject Funds Part 2 for his personal business ventures. He deposited the check into his own bank account (which had a very small balance), then made a series of complex transactions: withdrawing large sums, making time deposits, using those deposits as collateral for personal loans, and re-depositing the loan proceeds. During this period, M also used significant amounts from these accounts for his own purposes.

- Eventually, M, after adding some separately sourced cash to the remnants and traceable proceeds of Subject Funds Part 2, obtained a new check for ¥12,806,434. He sent this check directly to the Hyogo Prefecture agricultural association, misrepresenting it as their due government subsidy.

- The Hyogo association, however, found the payment procedure irregular (it didn't come through official channels). They put a hold on accepting the funds and consulted the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (Y – the State, effectively M's employer and one of the ultimate victims of M's broader fraudulent scheme).

- This inquiry led to an agreement: the Hyogo association would formally return the ¥12.8 million check to M. M, in turn, would then pay this same amount to the Ministry (Y) as partial restitution for the much larger sums M had defrauded from the Ministry through his various schemes. This was formalized, and after a special government ordinance enabled the out-of-budget-cycle payment, the Ministry (Y) then correctly paid the subsidy to the Hyogo association.

- X Sues Y for Unjust Enrichment: X (the Ibaraki association, whose credit was fraudulently used by A to obtain the loans that became Subject Funds Part 1 and Part 2) sued Y (the State/Ministry) for unjust enrichment. X sought the return of both amounts, arguing that Y had ultimately benefited from funds for which X was now wrongfully liable.

- High Court Rulings:

- Regarding Subject Funds Part 1: The High Court rejected X's claim. It found that the Ministry official who received these funds from A did so in good faith (believing it was a legitimate return of overpaid subsidies by X). Therefore, the Ministry's (Y's) receipt of these funds was deemed to have a "legal cause."

- Regarding Subject Funds Part 2: The High Court also rejected X's claim for this amount. It reasoned that M's actions – depositing the funds into his personal account, commingling them with other money, using portions for personal business, and then replenishing the sum before the final payment to the Ministry – had broken the chain of identity. The funds the Ministry eventually received from M as restitution could no longer be considered the "same" funds that A had originally given to M (which originated from the loan taken in X's name). Thus, the High Court found no direct causal link between X's loss (being liable for the second loan) and Y's ultimate gain (receiving restitution from M).

X appealed the High Court's decision concerning Subject Funds Part 2 to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Framework for Recovery

The Supreme Court, on September 26, 1974, issued a nuanced judgment. It upheld the High Court's dismissal of X's claim for Subject Funds Part 1. However, it overturned the High Court's dismissal regarding Subject Funds Part 2 and remanded this part of the case for further proceedings, establishing a critical legal framework for such "payment with embezzled funds" situations.

The Supreme Court laid out two key conditions that must be met for the original victim (X) to successfully claim unjust enrichment from the ultimate recipient (Y) of funds misappropriated by an intermediary (M):

1. Sufficient Causal Link (Even with Commingled Money)

The Court rejected a narrow interpretation of causation that would require tracing the exact same physical banknotes from the victim to the embezzler to the recipient.

- It stated that the causal link necessary for an unjust enrichment claim is not broken merely because the embezzler (M) commingled the victim's (X's) money with their own funds, exchanged it for other currency, deposited it into a bank account, spent part of it for other purposes and then later replenished the amount with different funds before making the payment to the recipient (Y).

- Instead, a causal link still exists if, from a "societal common sense perspective" (社会通念上 - shakai tsūnenjō), it can be recognized that the embezzler (M) effectively used the victim's (X's) money (or the value derived therefrom) to benefit the recipient (Y). There must be a sufficient "connection" (連結 - renketsu) that can be reasonably perceived.

- Applying this to Subject Funds Part 2, the Supreme Court found that the High Court erred in concluding that M's interim actions automatically severed the link. The funds Y (Ministry) received from M as restitution could, from this broader societal perspective, still be considered as originating from the money X lost.

2. Recipient's (Y's) Bad Faith or Gross Negligence

Once a sufficient causal link is established, the second crucial condition concerns the state of mind of the recipient (Y) at the time they received the payment from the embezzler (M).

- If the recipient (Y) received the money from the embezzler (M) while acting in "bad faith" (悪意 - akui) – meaning Y knew the funds were illicitly obtained from the victim (X) – or if Y had "gross negligence" (重大な過失 - jūdai na kashitsu) – meaning Y was not aware but failed to realize the illicit origin due to a severe lack of due care – then the recipient's (Y's) acquisition of that money is deemed to lack "legal cause" (法律上の原因 - hōritsu-jō no gen'in) in relation to the original victim (X).

- In such a case, the recipient (Y) is liable to the victim (X) for unjust enrichment.

Remand for Further Findings

The Supreme Court found that the High Court, having erroneously denied a causal link for Subject Funds Part 2, had not proceeded to make factual findings regarding the Ministry's (Y's) state of mind (bad faith or gross negligence) when it received the restitution payment from M. Therefore, the case was sent back to the High Court specifically to investigate and rule on this point. If the Ministry was found to have been in bad faith or grossly negligent about the source of M's restitution money, X's unjust enrichment claim against Y could succeed.

Unpacking the "Payment with Embezzled Funds" Doctrine

This 1974 Supreme Court judgment was pivotal in establishing a clearer framework for "payment with embezzled funds" (騙取金銭による弁済 - henshu kinsen ni yoru bensai) cases in Japan, moving away from some earlier, more inconsistent approaches.

Evolution from Prior Case Law

- Early Approaches: Older Daishin-in (former Supreme Court) rulings often focused on whether the victim still technically "owned" the specific banknotes when they reached the recipient. If the embezzled money was commingled with the embezzler's own funds, the victim's property right in the specific notes was often deemed lost, and this was used to deny a direct causal link for unjust enrichment claims against the ultimate recipient. Another defense for the recipient was "immediate acquisition" (即時取得 - sokuji shutoku), similar to a bona fide purchaser rule for movables, if they received specific cash in good faith. These approaches were akin to trying to apply property law tracing concepts to highly fungible money.

- The "Possession = Ownership" Shift for Money: This traditional approach became problematic once Japanese law firmly established that, for money, possession generally equates to ownership (e.g., a 1964 Supreme Court case). Under this view, the victim would lose "ownership" of the specific cash as soon as the embezzler took possession.

- A 1967 Supreme Court Precursor: A 1967 Supreme Court case had denied a victim's unjust enrichment claim if the third-party recipient had received the payment from the embezzler in good faith, finding that the recipient then had "legal cause" for the enrichment.

- The 1974 Judgment's Refinements: The 1974 judgment built upon and refined this. It explicitly delinked the "causal relationship" requirement from the need to trace specific physical banknotes, introducing the more flexible "societal common sense connection" standard. Significantly, it also tightened the standard for protecting the recipient: mere "good faith" on the recipient's part was no longer an absolute shield. The recipient would only be protected if they were free from both "bad faith" and "gross negligence."

The Underlying "Fairness" Rationale

The Supreme Court prefaced its framework by stating that the unjust enrichment system is based on "fairness." While not fully elaborated in the judgment itself, legal commentary suggests that the "bad faith or gross negligence" standard for the recipient is analogous to the level of culpability required to defeat the rights of an acquirer of negotiable instruments (e.g., under Japanese laws on bills and checks). This implies the Court was trying to strike a balance: protecting the original victim of embezzlement while also providing a degree of security and finality to transactions for recipients of payments, especially when those recipients are themselves creditors being paid a due debt. A creditor receiving payment should only be made to return it to a third-party victim if the creditor was significantly blameworthy (i.e., knew or was grossly negligent in not knowing) about the tainted source of the funds.

Conclusion

The 1974 Japanese Supreme Court decision offers a critical pathway, albeit a qualified one, for victims of financial fraud or embezzlement to potentially recover their losses from third parties who ultimately received the misappropriated funds. Recovery is not automatic. It hinges on the victim demonstrating two key elements: first, a traceable "societal common sense connection" between their lost money and the funds that reached the recipient, even if the money was commingled or transformed along the way. Second, and crucially, the victim must show that the recipient, when they received the payment from the wrongdoer, acted in "bad faith" (knowing the funds were tainted) or with "gross negligence" (being severely careless in not realizing it). This framework attempts to balance the equities between the innocent victim and a recipient who might also have a legitimate claim against the wrongdoer, making the recipient's state of mind a decisive factor.