Flowing Rights: Supreme Court Limits Irrigation Permit Holder's Power to Block Wastewater Discharge

Judgment Date: July 18, 2019

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

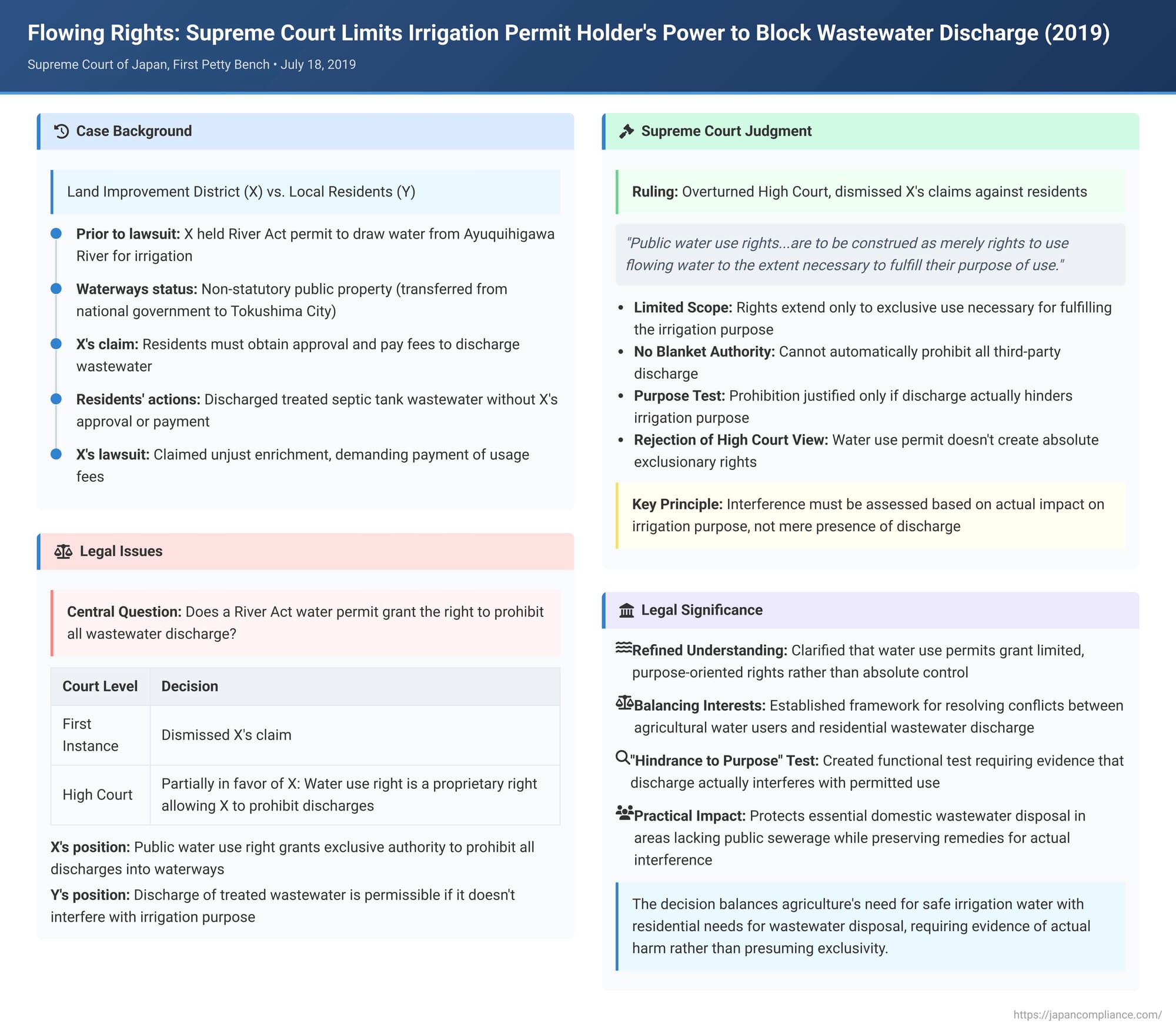

The use of public water resources often involves a delicate balance between various interests. A 2019 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a conflict between a land improvement district holding a permit to draw river water for irrigation and local residents discharging treated domestic wastewater into the waterways carrying this irrigation water. The Court clarified that a "public water use right" granted under the River Act does not confer an absolute authority to prohibit all third-party discharges, but is limited to ensuring the fulfillment of the permit's specific purpose.

The Disputed Waterways: Irrigation Needs vs. Residential Discharge

The case centered on X, a Land Improvement District in Tokushima Prefecture. Land improvement districts are quasi-public entities responsible for projects like irrigation and drainage for agriculture. X held a permit under Article 23 of the River Act, allowing it to draw water from the Ayuquihigawa River for irrigation purposes[cite: 1]. This water was channeled through a network of main and branch waterways ("the Waterways") to be used by X's members for their agricultural activities[cite: 1].

These Waterways themselves had a complex status. They were originally "non-statutory public property" (hōteigai kōkyōbutsu) – public assets not specifically governed by statutes like the Road Act or River Act – which had been transferred from the national government to Tokushima City. The City was formally responsible for their management under a local ordinance[cite: 1]. While the City undertook some improvement and repair works, X, the Land Improvement District, had been de facto responsible for the overall maintenance of the Waterways[cite: 1].

X's articles of incorporation included provisions stating that unauthorized discharge of wastewater into the irrigation and drainage channels it managed was prohibited. They stipulated that anyone wishing to use these channels (e.g., for discharge) must obtain X's approval, enter into a formal use contract, and pay a usage fee determined by X's standards[cite: 1].

The defendants, Y et al., were residents who owned land or lived near these Waterways. As their area was not served by public sewerage, they treated their domestic wastewater (including sewage from toilets) using individual or collective septic tanks (jōkasō) and then discharged the treated effluent into X's Waterways. They did so without obtaining X's approval or paying any fees[cite: 1].

X filed a lawsuit against Y et al., claiming unjust enrichment. X argued that the residents' discharge of wastewater into the Waterways infringed upon its alleged exclusive right to manage the water within these channels. X asserted that Y et al. had gained a benefit equivalent to the usage fees X would have charged, and that X had suffered a corresponding financial loss. X therefore demanded payment of these deemed usage fees plus late payment charges[cite: 1].

Lower Court Split: Exclusive Right or Permissible Use?

- The First Instance court dismissed X's claim[cite: 1].

- On appeal, the High Court partially found in favor of X, the Land Improvement District. It held that a right to use river water obtained under a River Act Article 23 permit is a proprietary right, akin to a real right (bukken-teki na zaisan-jō no kenri), to exclusively occupy the flowing water. Based on this premise, the High Court concluded that X possessed an exclusive right to manage the water in the Waterways and could therefore prohibit third parties, like Y et al., from discharging wastewater into them[cite: 1].

Y et al. appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Clarification: Water Use Rights are Not Absolute

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on July 18, 2019, overturned the High Court's ruling that had favored X. It ultimately dismissed X's claims against the residents[cite: 1]. The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning was a more constrained interpretation of the nature and scope of public water use rights:

1. Limited to Purpose Fulfillment:

The Court began by referencing a precedent from 1962 (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, April 10, 1962, Minshū Vol. 16, No. 4, p. 699). It reiterated that:

"Public water use rights, considering they exist over public water which is a public utility, are to be construed as merely rights to use flowing water to the extent necessary to fulfill their purpose of use"[cite: 1].

2. No Automatic Right to Prohibit All Third-Party Discharge:

Building on this principle, the Court stated:

"They [public water use rights] should not be understood to include the authority to exclude the use of flowing water by others beyond the extent necessary to fulfill that purpose of use"[cite: 1].

Applying this to the current case, the Supreme Court reasoned:

"Therefore, while X [the Land Improvement District] can be said to have the right to exclusively use the water flowing in the Waterways (which X draws under its River Act Article 23 permit for irrigation purposes) to the extent necessary to fulfill that irrigation purpose, X cannot immediately prohibit third parties [Y et al.] from discharging wastewater into the Waterways based solely on this [public water use right]"[cite: 1].

Essentially, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in granting X a blanket right to prohibit all discharges based on its water use permit. The mere fact of holding an irrigation permit does not automatically give the permit holder the power to stop any and all discharges by others into the channels carrying that water, unless such discharges actually interfere with the "purpose of irrigation" to the necessary extent.

Unpacking the Decision: Nature of Public Water Use Rights

This judgment provides crucial clarification on the scope of rights conferred by a water use permit under the River Act.

A Permitted Right, Not Absolute Ownership of Water:

A water use permit granted under the River Act is an example of what legal scholars term a "special grant" or "patent" (tokkyo). It allows a specific entity to exclusively occupy and use public flowing water for a defined purpose (like irrigation, hydropower, etc.). This is distinct from the general public's "free use" of water for minor, temporary purposes such as recreation or incidental domestic use, which typically does not require a permit[cite: 1].

While these permitted water rights have a public character due to their regulation under the River Act, they also serve the private interests of the permit holder[cite: 1]. They are recognized as proprietary rights that can be inherited and, with the approval of the river administrator, transferred between private parties[cite: 1]. Disputes concerning them are generally handled through civil litigation, and infringements can lead to tort claims for damages or injunctions under the Civil Code[cite: 1].

However, as the Supreme Court emphasized, this right is not equivalent to outright ownership of the water itself. It is a right to use the water, and this use is qualified by its permitted purpose.

Balancing Irrigation Needs with Other Water Uses:

The Supreme Court's decision in this case, building upon its 1962 precedent, underscores that the exclusivity of a water use right is tied to what is "necessary to fulfill [the] purpose of use"[cite: 1]. This means that a permit holder for irrigation cannot automatically exclude any other use or discharge by a third party simply because that third party is interacting with the water the permit holder has drawn.

When Can Discharge Be Prohibited? (The "Hindrance to Purpose" Test):

The judgment implies that a prohibition on discharge by third parties could be justified if that discharge genuinely hinders the permit holder's ability to use the water for its permitted irrigation purpose[cite: 1]. For example:

- If the discharged wastewater (even if treated) contains substances that make the water unsuitable for irrigation, thereby harming crops or soil.

- If the volume of discharged water is so large that it causes the irrigation channels to overflow or otherwise disrupts the irrigation system.

In such scenarios, the discharge would indeed be infringing upon the permit holder's right to exclusively use the water "to the extent necessary to fulfill the irrigation purpose," and legal remedies like injunctions or damages might be available[cite: 1]. This Supreme Court decision, therefore, doesn't give a green light to all discharges but rather sets a standard: the impact on the permitted purpose is the crucial test. The previous focus of many water rights cases was on quantitative reduction of water by third parties; this ruling explicitly extends a similar "purpose-fulfillment" standard to issues of water quality arising from discharges into water already drawn by the permit holder[cite: 1].

Broader Context: Non-Statutory Public Property and Land Improvement Law

The commentary accompanying the case highlights several related legal dimensions:

- Management of the Waterways: The Waterways were "non-statutory public property" managed by Tokushima City[cite: 1]. The Land Improvement District X had no direct legal authority over the management of these waterways as public property based on this status, nor could it unilaterally impose contractual obligations or usage fees on residents based solely on its own articles of incorporation[cite: 1]. Justice Hiroshi Koike, in his supplementary opinion, pointed to the unclear legal relationship between Tokushima City (the formal manager) and X (the de facto maintainer and user) as a contributing factor to such disputes, emphasizing the need for clarity[cite: 1]. However, the Supreme Court's ruling focused specifically on the limits of X's rights derived from its water use permit, separate from the City's management responsibilities[cite: 1].

- Land Improvement Act: The Land Improvement Act (Article 57-3) does provide a mechanism for land improvement districts to address harmful discharges into agricultural channels they manage under specific regulations, if such discharges cause or risk "significant hindrance" to their management functions[cite: 1]. This provision was not applicable here as X reportedly did not have the prerequisite management regulations in place[cite: 1]. Even if it were, the threshold ("significant hindrance to management") is high and specifically tied to the management of the channels, not necessarily the quality of water for irrigation unless it also impacts management[cite: 1]. The rights derived from a water use permit can offer a more direct route to protect the actual use of the water for its permitted purpose[cite: 1].

- Water Rights Beyond the River Area: Water drawn under a permit and flowing in channels outside the designated river area is generally considered to be under the water user's management, not the river administrator's[cite: 1]. This, however, does not prevent the effects of the public water use right from extending to these external channels, as the Supreme Court implicitly recognized by applying its principles to the Waterways in this case[cite: 1].

- Nature of "Public Water Use Right": It's important to distinguish the "public water use right" (a right to use flowing water) from any notion of private ownership of the flowing water itself (which is generally not permitted under River Act Art. 2(2))[cite: 1]. The Supreme Court's affirmation of an "exclusive right to use" the drawn water, even outside the river area, implies that effective legal remedies, including injunctions and damages for infringement, should be available to protect this right[cite: 1].

The Legacy of Administrative Guidance on Discharge Consent

Interestingly, the legal commentary notes a historical context of administrative practice in Japan where obtaining consent from neighbors or downstream users was often required as part of the approval process for installing septic tanks and discharging treated wastewater, particularly when applying for building confirmations[cite: 4]. This practice came under scrutiny for potentially lacking clear legal basis and constituting inappropriate administrative guidance. Following critiques (notably by Professor Yasutaka Abe in the late 1980s), official government notices were issued in the 1990s to ensure such consent requirements were not improperly imposed by local authorities, especially when the discharge met legal standards and did not cause actual harm[cite: 4]. The Land Improvement District's attempt in this case to establish a fee-based approval system might be seen, in part, as a response to the declining effectiveness of informal consent mechanisms[cite: 4]. Professor Abe's earlier analyses, which advocated for relying on legally established frameworks and addressing actual damages through civil law, are noted as presciently aligning with the principles underlying this Supreme Court decision[cite: 4].

Conclusion: Navigating Shared Water Resources and the Limits of Permitted Rights

The 2019 Supreme Court decision refines the understanding of public water use rights in Japan. It confirms that while such rights grant an exclusive entitlement to use water, this exclusivity is not absolute but is bounded by the necessity of fulfilling the specific, permitted purpose. Permit holders cannot automatically prohibit all third-party discharges into waterways carrying their permitted water unless those discharges demonstrably interfere with their designated use. This ruling emphasizes a balanced approach, requiring a factual assessment of actual or likely harm to the permitted water use before interference by others can be legally curtailed. It also indirectly highlights the importance of clear legal frameworks for managing shared resources like local waterways and the distinct roles of water use rights, public property management, and specific statutes like the Land Improvement Act.