Floating Stock Security in Japan: Navigating Duplicate Interests and Debtor's Sales

Date of Judgment: July 20, 2006

Case Name: Action for Confirmation of Ownership

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

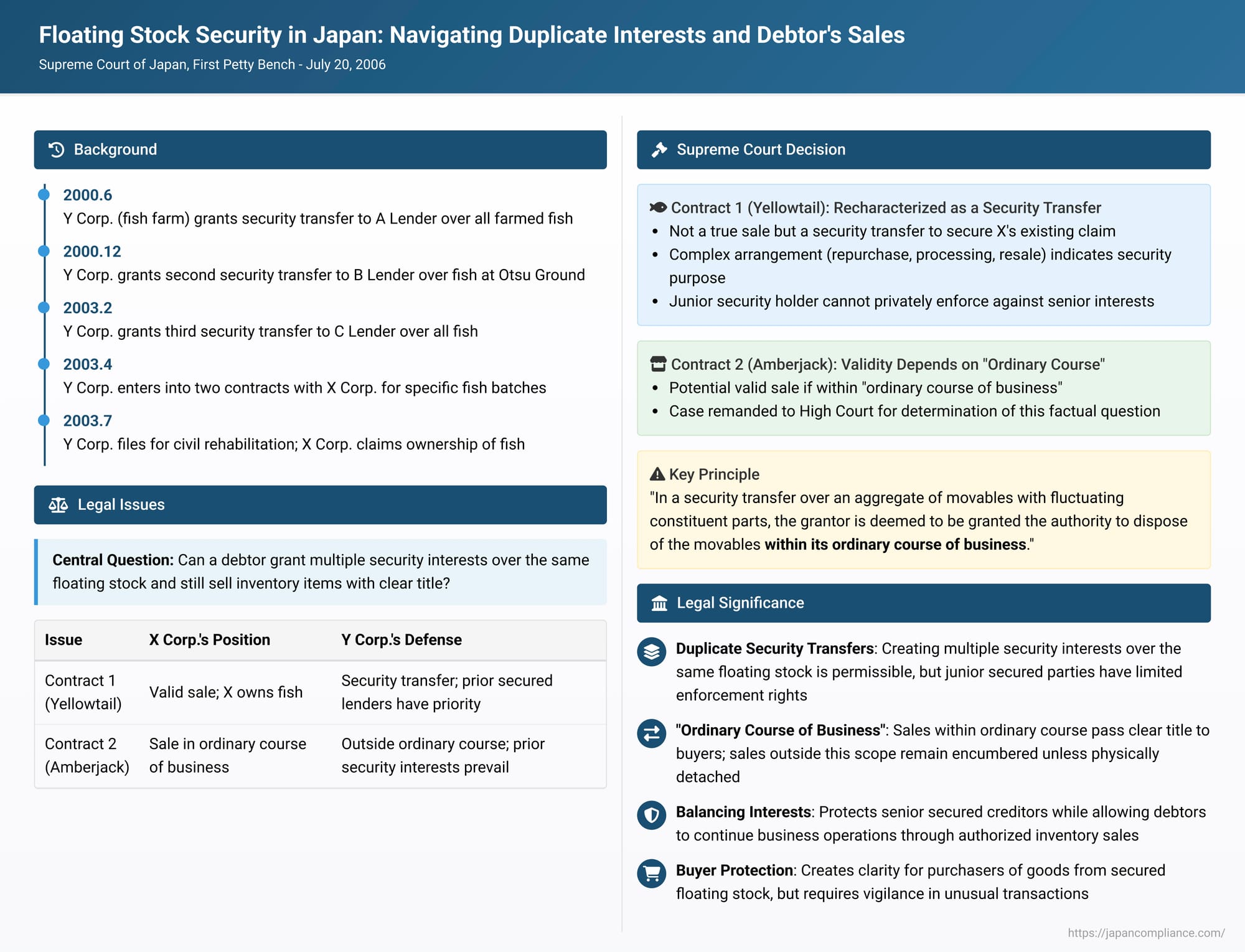

Securing loans against a business's fluctuating inventory – often called "floating stock" – presents distinct legal challenges compared to securing specific, identifiable assets. Japanese law, primarily through judicially developed principles of "security transfer of an aggregate of movables" (shūgō dōsan jōto tanpo), has created ways for businesses to use their inventory as collateral while continuing to operate and sell from that stock. A Supreme Court judgment on July 20, 2006, delved into two critical complexities arising from such arrangements: firstly, the rights and limitations when a debtor creates multiple, overlapping security transfers over the same inventory in favor of different creditors; and secondly, the extent to which a debtor can sell items from the secured inventory and pass clear title to a purchaser.

The Fish Farm's Finances: Multiple Security Transfers and Disputed Sales

The case involved Y Corp., a fish farming company, which had entered into several financing and supply arrangements that led to a dispute with X Corp. over ownership of specific batches of farmed fish.

- Y Corp.'s Prior Security Transfers (Floating Stock):

- To A Lender (June 30, 2000): Y Corp. granted A Lender a root security transfer over all its farmed fish located in specified net cages at Ko Fishing Ground, Otsu Fishing Ground, and other designated fishing areas. This was to secure Y Corp.'s debts for fish feed purchases, up to a maximum of ¥2.5 billion. The security interest was perfected by "constructive delivery" (sen'yū kaitei), where Y Corp. continued to possess and manage the fish but acknowledged holding them for A Lender. The agreement permitted Y Corp. to sell fish in its "ordinary course of business."

- To B Lender (December 7, 2000): Y Corp. granted B Lender another root security transfer, this time covering all farmed fish specifically in the net cages at Otsu Fishing Ground, to secure debts up to ¥1 billion. This was also perfected by constructive delivery. The agreement permitted Y Corp. to use the fish without charge (implying for cultivation).

- To C Lender (February 14, 2003): Y Corp. granted a third root security transfer to C Lender, again covering all its farmed fish in Ko, Otsu, and other specified fishing grounds, to secure debts from commercial and financial transactions up to ¥3 billion. This was also perfected by constructive delivery. Y Corp. was permitted to sell fish in its ordinary course of business, with sales proceeds usable as working capital with C Lender's consent.

- Y Corp.'s Disputed Contracts with X Corp. (April 30, 2003): After these comprehensive security interests were in place, Y Corp. entered into two specific agreements with X Corp. concerning portions of its fish stock, which were already subject to the prior security transfers to A, B, and C Lenders:

- Contract 1 (Yellowtail for further farming and processing): This complex agreement involved Y Corp. nominally "selling" to X Corp. approximately 130,000 farmed yellowtail located in 21 specific net cages within Otsu Fishing Ground ("Fish 1"). The "sale price" was to be set off against an existing debt Y Corp. owed to X Corp. Ownership was stated to transfer to X Corp. immediately, and the cages were to be marked as X Corp.'s property. Simultaneously, X Corp. "entrusted" (yotaku) these same fish back to Y Corp. for continued rearing and management until April 30, 2004, with Y Corp. bearing the rearing costs. The agreement further stipulated that Y Corp. would later "repurchase" these fish from X Corp., process them (e.g., into fillets), and then "sell" the processed fish back to X Corp. X Corp. would then sell these processed products to an external party, D Purchaser. The payment for Y Corp.'s repurchase from X Corp. was to be settled against the price of Y Corp.'s sale of processed fish to X Corp. If Y Corp. faced insolvency, X Corp. was granted the right to sell the originally "entrusted" fish to a third party to recover its claim.

- Contract 2 (Amberjack for immediate resale): Under this agreement, Y Corp. "sold" to X Corp. approximately 270,000 farmed amberjack ("Fish 2"). X Corp.'s stated purpose was to move all these fish from Y Corp.'s net cages by July 31, 2003, for resale to third parties. Until such removal, Y Corp. was to manage the fish on X Corp.'s behalf.

- Y Corp.'s Civil Rehabilitation: On July 30, 2003, Y Corp. filed for civil rehabilitation proceedings, which were formally commenced on August 4, 2003. X Corp. subsequently sued Y Corp. for the delivery of Fish 1 and Fish 2, asserting ownership based on Contracts 1 and 2. Y Corp. defended by arguing, firstly, that Contracts 1 and 2 were not true sales but were themselves security transfer agreements, and secondly, that because A, B, and C Lenders held prior perfected security transfers over all these fish, X Corp. could not have acquired ownership unless it met the stringent conditions for "immediate acquisition" (sokuji shutoku) of title from a non-owner, which Y Corp. claimed were not fulfilled.

The Lower Courts' Rulings

The District Court found both contracts to be sales but ultimately denied X Corp.'s claim, agreeing that X Corp. could not acquire clear ownership over already encumbered assets without satisfying the requirements of immediate acquisition, which it failed to do. The High Court, however, also found both contracts to be sales but reached a different conclusion on ownership. It held that under Y Corp.'s security agreements with A and C Lenders, Y Corp. retained the power to sell fish in its ordinary course of business and thereby convey good title to a third-party purchaser. The High Court concluded that X Corp. had acquired ownership of both Fish 1 and Fish 2 based on this retained power of Y Corp. It therefore reversed the District Court and ruled in favor of X Corp. Y Corp. appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (July 20, 2006): A Tale of Two Contracts

The Supreme Court delivered a nuanced judgment, analyzing each contract separately and ultimately reversing the High Court's decision.

Contract 1 (Yellowtail for farming) – Recharacterized as a Junior Security Transfer:

The Supreme Court disagreed with the lower courts' characterization of Contract 1 as a simple sale. It found that the agreement's true nature was that of a security transfer, intended to secure X Corp.'s pre-existing claim against Y Corp. The Court pointed to several factors:

- No actual transfer of physical possession of Fish 1 to X Corp. at the time of the contract; Y Corp. continued to rear and manage them.

- The purported "sale price" was not a fresh payment but was set off against Y Corp.'s existing debt to X Corp.

- The complex arrangement involving Y Corp.'s "repurchase" of the fish, processing them, and then "reselling" them to X Corp., with the ultimate aim being the recovery of X Corp.'s original claim through the final sale to D Purchaser.

- The clause allowing X Corp. to sell the fish if Y Corp. became insolvent further indicated a security purpose.

(This recharacterization aligns with principles from prior Supreme Court cases, e.g., Supreme Court, February 7, 2006, Minshū Vol. 60, No. 2, p. 480 – the "M93 case" – which established that a sale with a repurchase option intended for debt security should be treated as a security transfer).

Having recharacterized Contract 1 as a junior security transfer by X Corp. over Fish 1, the Supreme Court then considered its validity and enforceability in light of the pre-existing senior security transfers held by A, B, and C Lenders:

- Duplicate Security Transfers Permissible, but Enforcement by Junior Limited: The Court acknowledged that creating overlapping security transfers over the same aggregate of movables is, in itself, permissible. However, it placed a crucial limitation on the junior secured party's enforcement rights: "Even if it is permissible to create duplicate security transfers, if a junior security transfer holder with an inferior interest were allowed to exercise a right of private enforcement, senior security transfer holders would not be given an opportunity to exercise their priority rights, unlike in formal civil execution proceedings where distribution procedures are established, and their security transfers could become effectively meaningless. Such private enforcement by a junior security transfer holder, which would lead to such a result, cannot be permitted."

- No Immediate Acquisition by X Corp.: X Corp. argued it had received possession of Fish 1 by constructive delivery under Contract 1. However, the Court stated that constructive delivery alone does not enable a party to claim immediate acquisition (sokuji shutoku) of unencumbered title in a way that would defeat pre-existing, perfected senior security interests.

- Result for Fish 1: Consequently, X Corp.'s claim for delivery of Fish 1, whether viewed as a claim by an owner (which it was not, due to recharacterization) or as an attempt to enforce its junior security interest through private means (which was impermissible against senior interests), had to fail. The Supreme Court therefore reversed the High Court on this point and upheld the District Court's original dismissal of X Corp.'s claim for Fish 1.

Contract 2 (Amberjack for resale) – A Potential Sale, but Subject to "Ordinary Course of Business" and "Detachment":

The Supreme Court found no specific grounds to recharacterize Contract 2 as a security transfer; it proceeded on the basis that it was intended as a genuine sale agreement. The key question then became whether Y Corp. could pass clear title to X Corp. given the existing security transfers to A, B, and C Lenders.

- Grantor's Power to Dispose of Secured Goods in the "Ordinary Course of Business": The Court reaffirmed a vital principle for security transfers over fluctuating aggregates like inventory or fish stock: "In a security transfer over an aggregate of movables with fluctuating constituent parts, as it is naturally anticipated that the content of the aggregate will change through the business activities of the security transfer grantor, the grantor is deemed to be granted the authority to dispose of the movables constituting the object of the security transfer within its ordinary course of business. The counterparty to a disposition made within this authority acquires definitive ownership of the said movables, unencumbered by the constraints of the security transfer." The Court noted that Y Corp.'s agreements with senior lenders A and C explicitly contained clauses confirming this right of ordinary course disposal.

- Disposal Outside the "Ordinary Course of Business": The Court then set out the rule for sales not meeting this criterion: "On the other hand, if the grantor of a perfected security transfer over an aggregate of movables effects a sale disposition of the objective movables that exceeds the ordinary course of business, since such disposition is not based on the aforementioned authority, the counterparty to such disposition cannot succeed to ownership of the objective movables, unless it is found that the movables have been detached from the aggregate object of the said security transfer, such as by being moved out from the storage location stipulated in the security transfer agreement."

- Remand for Fish 2: In the case of Fish 2, the Supreme Court found no circumstances suggesting that these fish had been physically removed from the specified fishing grounds (the secured locations) in a way that would detach them from the encumbered aggregate prior to or independent of the disputed sale itself. Therefore, whether X Corp. had acquired valid ownership of Fish 2 depended critically on whether the sale under Contract 2 constituted a transaction "within Y Corp.'s ordinary course of business." The High Court had not made a specific finding on this crucial factual point. Consequently, the Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision regarding Fish 2 and remanded this part of the case back to the High Court for further trial to determine if the sale was within the ordinary course of Y Corp.'s business.

Key Principles for Security over Aggregates of Movables

This 2006 judgment builds upon and refines earlier Supreme Court precedents (like the M96 case: Supreme Court, November 10, 1987, Minshū Vol. 41, No. 8, p. 1559) concerning security over fluctuating assets:

- Validity and Specificity of the Aggregate: The fundamental principle that an entire, evolving stock of goods can be treated as a single object for a security transfer is upheld, provided its "type, location, and quantitative range" are sufficiently specified to define the collateral pool.

- Duplicate Pledging (Security Transfers): While permissible in principle for a debtor to grant security interests to multiple creditors over the same aggregate, this judgment severely curtails the ability of a junior secured party to privately enforce their security interest (e.g., by demanding possession or selling the assets themselves). Such private enforcement by a junior party is not allowed if it would effectively bypass the senior secured parties' prior rights, as it lacks the priority-ordering mechanisms inherent in formal civil execution (foreclosure) proceedings.

- Sales by the Debtor from Secured Stock: This is a critical area for businesses using inventory as collateral.

- "Ordinary Course of Business" Sales: The debtor (grantor of the security transfer) generally retains the power to sell items from the secured inventory in its "ordinary course of business." Purchasers in such transactions acquire clear title, free of the security interest. This is essential for the debtor to continue operating.

- Sales "Outside the Ordinary Course of Business": If a sale is deemed to be outside the ordinary course of business, the purchaser does not acquire clear title, and the security interest continues to encumber the goods, unless the goods have already been effectively "detached" from the secured aggregate (e.g., by being physically removed from the specified secured location prior to the unauthorized sale).

What Constitutes "Ordinary Course of Business"?

The Supreme Court remanded the case for a determination of whether the sale of Fish 2 was in Y Corp.'s "ordinary course of business." While the judgment itself does not provide an exhaustive list of factors for this determination, legal analysis typically considers elements such as:

- The nature and scale of the debtor's usual business operations.

- The type, quantity, and price of the goods sold in the disputed transaction compared to normal sales.

- The identity and relationship of the buyer.

- Whether the sale was part of a regular pattern or an unusual, isolated transaction (e.g., a bulk sale of a significant portion of inventory, especially when facing financial distress, might be outside the ordinary course).

- The impact of the sale on the secured creditor's interests and whether it significantly depletes the collateral pool without replenishment.

"Detachment" from the Secured Aggregate

The concept of goods being "detached" from the secured aggregate if sold outside the ordinary course of business (e.g., by removal from the specified location) is another important point. This judgment suggests that such physical detachment might allow a buyer to acquire clear title even if the sale itself was not in the ordinary course. However, the precise conditions under which detachment alone, without an ordinary course sale, would free the goods from the security interest (e.g., whether the buyer would still need to prove immediate acquisition) remain subject to further interpretation. The judgment does not fully clarify whether mere movement of goods by the debtor to a different location, without any disposition, would extinguish the security interest; legal commentary suggests this is unlikely as ownership has already been transferred for security purposes.

Implications for Lenders, Borrowers, and Purchasers

This 2006 Supreme Court decision has several practical implications:

- For Senior Lenders with Floating Stock Security: It affirms the general strength and priority of their security interest over the entire defined aggregate, including after-acquired components. It also implicitly accepts their understanding that the debtor can continue to make ordinary course sales.

- For Junior Lenders: It highlights significant risks. While taking junior security over already encumbered floating stock is not prohibited, the ability to privately enforce that security is severely limited if senior interests exist. Junior lenders may have to rely on formal execution proceedings or the surplus after senior creditors are satisfied.

- For Debtors (Borrowers): The framework allows businesses to use their fluctuating inventory as collateral, providing necessary flexibility for ordinary sales. However, it also imposes a responsibility to operate within the "ordinary course" when disposing of secured assets, lest they convey encumbered title or breach their security agreements.

- For Purchasers from such Debtors: Buyers of goods from a business whose inventory is known or likely to be subject to a floating stock security transfer must exercise diligence. Purchases clearly within the seller's ordinary course of business are generally safe. However, unusual transactions (e.g., bulk purchases at deep discounts from a company in distress) carry the risk that the buyer might not receive clear title if the sale is deemed outside the ordinary course and the goods remain tied to the secured aggregate.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment of July 20, 2006, provides crucial insights into the complex dynamics of security transfers over fluctuating aggregates of movables. It navigates the tension between allowing a debtor to continue business operations by selling from secured inventory and protecting the priority of secured creditors. The decision confirms the validity of such security arrangements but imposes significant restrictions on the private enforcement rights of junior secured parties when senior interests exist. Furthermore, it establishes a critical distinction regarding the debtor's power to sell secured inventory: sales made "within the ordinary course of business" generally pass clear and unencumbered title to purchasers, whereas sales outside this scope may result in the purchaser taking the goods subject to the pre-existing security interest, unless the goods have been clearly "detached" from the secured aggregate. The factual determination of what constitutes the "ordinary course of business" remains a key element in resolving disputes in this area of commercial law.