Flexible Security: Japanese Supreme Court on Provisional Attachment's Reach Beyond the Initially Stated Claim

Date of Supreme Court Decision: February 23, 2012

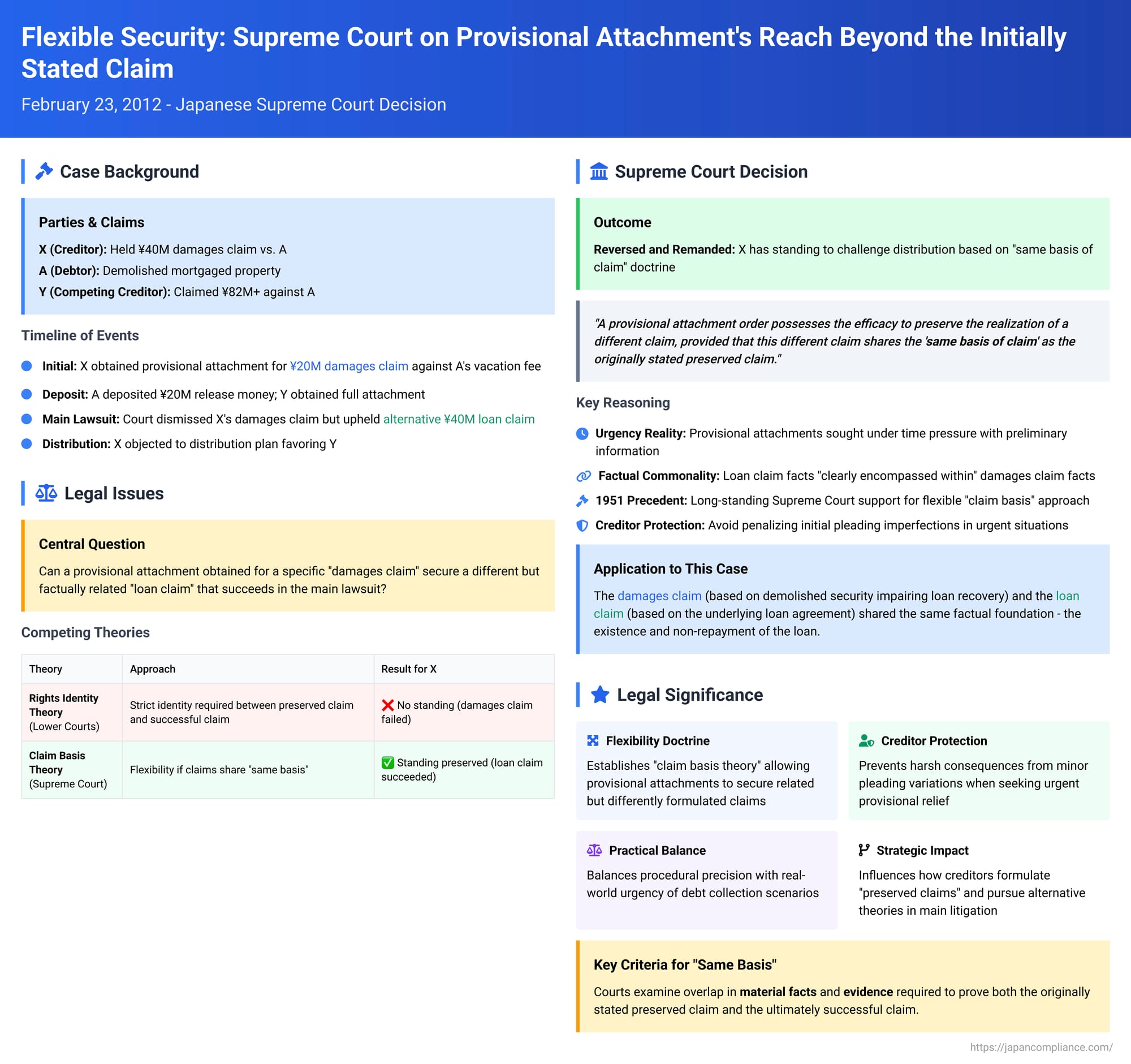

Provisional attachment (仮差押え - karisashiosae) is a vital tool in Japanese civil procedure, allowing a creditor to secure a debtor's assets to ensure that a future or pending judgment can be satisfied. A critical question often arises concerning the relationship between the specific claim for which the provisional attachment was initially granted (the "preserved claim" – 被保全債権 - hihozen saiken) and the claim that is ultimately validated in the main lawsuit. If the creditor wins the main lawsuit but on a legal ground slightly different from, though factually related to, the one originally cited in the provisional attachment order, does the provisional attachment still effectively secure this successfully established claim? A 2012 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Heisei 23 (Ju) No. 268) provided significant clarification, endorsing a more flexible approach based on the concept of the "same basis of claim."

The Factual Web: A Loan, Damaged Security, and Competing Creditors

The case involved X (the creditor who obtained the provisional attachment), A (the debtor), and Y (another creditor of A who competed with X for A's assets).

- The Underlying Dispute and Provisional Attachment: X asserted a damages claim of ¥40 million against A. This claim arose because A had allegedly infringed X's neteitōken (a type of revolving mortgage) by demolishing the mortgaged property without X's consent. This demolition, X argued, made it difficult for X to recover a separate ¥40 million loan previously extended to A (referred to as the "Honken Kashikin Saiken" – the Loan Claim).

- To secure ¥20 million of this damages claim (referred to as the "Honken Songai Baishō Saiken" – the Damages Claim), X obtained a provisional attachment order against a "vacation fee" (明渡料 - akewatashiryō, likely a payment A was due to receive from a third party, B, for vacating a property).

- Deposit of Release Money and Competing Attachment: A, the debtor, deposited the provisional attachment release money (仮差押解放金 - karisashiosae kaihōkin) of ¥20 million with the authorities. Under Japanese law, such a deposit typically causes the effect of the provisional attachment to shift from the originally targeted asset (A's claim against B for the vacation fee) to A's claim against the State for the return of this deposited money (the "Honken Kōtakukin Torimodoshi Seikyūken" – the Claim for Return of Deposited Money).

- Subsequently, Y, another creditor of A, obtained a full attachment order (based on an enforceable notarial deed for a debt exceeding ¥82 million) against A's Claim for Return of Deposited Money.

- The Distribution Dispute: With both X's provisional attachment (now effective against the deposited funds) and Y's full attachment targeting the same deposited money, a court-supervised distribution process commenced. A distribution plan was drafted, allocating approximately ¥3.89 million to X and approximately ¥16.11 million to Y.

- X objected to this plan by filing a "distribution objection lawsuit" (配当異議の訴え - haitō igi no uttae). X argued that Y's claim was fictitious and sought a modification of the distribution plan to have X receive the full ¥20 million (the amount of its provisional attachment and the deposited release money), with Y receiving only a nominal sum.

- The Parallel Main Lawsuit (X vs. A): Crucially, prior to and during this distribution dispute, X had been pursuing a main lawsuit against the debtor A (and other defendants). In this main lawsuit:

- X's primary claim was for damages (including the ¥40 million loan amount as a component of damages) resulting from A's tortious act of demolishing the mortgaged property, which impaired X's security for the Loan Claim. This Damages Claim was the one explicitly stated as the "preserved claim" in X's provisional attachment order.

- X also included an alternative (or preliminary) claim (予備的請求 - yobi-teki seikyū) for the straightforward repayment of the underlying ¥40 million Loan Claim itself.

- Outcome of the Main Lawsuit: The appellate court in X's main lawsuit against A ultimately dismissed X's primary Damages Claim. However, it upheld X's alternative Loan Claim, ordering A to repay the loan. This judgment became final and binding on March 26, 2010.

The Lower Courts' Strict View in the Distribution Dispute: No Preserved Claim, No Standing for X

In X's distribution objection lawsuit against Y, both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (on appeal) dismissed X's suit as improper, finding that X lacked the "benefit of suit" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki). Their reasoning was:

- X's right to participate in the distribution of the deposited money stemmed from its provisional attachment.

- The "preserved claim" specifically identified in that provisional attachment order was the Damages Claim.

- The main lawsuit had definitively concluded that this Damages Claim was non-existent (it was dismissed).

- Therefore, the very foundation of X's provisional attachment had collapsed. X no longer had a valid preserved claim to support its status as a provisional attachment creditor in the distribution proceedings.

- Consequently, even if Y's claim were found to be invalid, X would not be entitled to a larger share of the distributed funds because its own basis for claiming any share through the provisional attachment had been negated.

- The fact that X had won on its alternative Loan Claim in the main lawsuit was deemed irrelevant by these lower courts. They held that the Loan Claim was a different cause of action (訴訟物を異にする - soshōbutsu o koto ni suru) from the Damages Claim specified in the provisional attachment order, and thus the success on the Loan Claim could not retroactively validate or sustain the provisional attachment obtained for the (failed) Damages Claim.

X then brought a permitted appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Broader Interpretation: The "Same Basis of Claim" Doctrine Upholds Provisional Attachment's Efficacy

The Supreme Court, in its decision of February 23, 2012, reversed the lower courts' judgments and remanded the case to the Tokyo District Court for a trial on the merits of X's objection to Y's claim. The Supreme Court held that X did have standing to sue, based on a more flexible interpretation of the relationship between the preserved claim in a provisional attachment and the claim ultimately established in the main lawsuit.

Core Holding: The Supreme Court ruled that a provisional attachment order, even if granted for a specifically identified "preserved claim," also possesses the efficacy to preserve the realization of a different claim, provided that this different claim shares the "same basis of claim" (請求の基礎を同一にする - seikyū no kiso o dōitsu ni suru) as the originally stated preserved claim.

Rationale for this Flexible Approach:

- Urgency and Practicalities of Provisional Orders: The Court acknowledged that provisional attachment orders are often sought under conditions of urgency. Creditors may not have the luxury of time or complete information to perfectly and definitively formulate their legal claims at that preliminary stage. The evidentiary standard for obtaining a provisional remedy is a prima facie showing (somei), which is less rigorous than the full proof required in a main lawsuit.

- Preventing Undue Hardship on Creditors: To require strict identity between the claim precisely as described in the provisional attachment order and the claim ultimately successful in the main lawsuit would be unduly harsh on creditors. A creditor might, in the haste of seeking to preserve assets, mislabel their claim or formulate it in a way that is later refined or even altered (while remaining factually related) during the more thorough proceedings of the main lawsuit.

- Referencing Long-Standing Precedent (Supreme Court, 1951): The Court grounded its decision in its own long-standing precedent (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, October 18, 1951, Minshu Vol. 5, No. 11, p. 600). That earlier case, in the context of an "order to sue on the merits" (起訴命令 - kiso meirei – a procedure where a debtor can compel a provisional attachment creditor to promptly file their main lawsuit), had held that if the main lawsuit is filed based on a claim that shares the "same basis" as the preserved right stated in the provisional order, it satisfies the requirement that a main action be duly filed. This established precedent signaled a judicial willingness to look at the underlying factual commonality rather than insisting on rigid legal identity.

Application of the "Same Basis of Claim" Doctrine to This Case:

- The "preserved claim" stated in X's provisional attachment order was the Damages Claim. This claim was predicated on A's tortious act of demolishing the mortgaged property, which, in turn, impaired X's ability to recover its underlying Loan Claim against A. The damages sought explicitly included an amount equivalent to the unrecoverable loan.

- The Loan Claim, which X ultimately won in the main lawsuit, was based on the loan agreement itself and A's failure to repay.

- The Supreme Court found that the "factual circumstances giving rise to the Loan Claim were clearly encompassed within the factual circumstances giving rise to the Damages Claim." In other words, the existence of the loan and its non-repayment were essential factual predicates for X's Damages Claim as it had been formulated (i.e., damage resulting from the inability to recover that specific loan due to the destruction of security).

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the Loan Claim and the Damages Claim shared the "same basis of claim."

Consequence for X's Standing:

Because X obtained a final and binding judgment upholding its Loan Claim, and this Loan Claim was deemed to share the same "basis of claim" as the Damages Claim originally specified as the preserved claim in the provisional attachment order, X retained its status as a provisional attachment creditor. The provisional attachment remained effective to secure the now-judicially-confirmed Loan Claim.

As a result, X had a legitimate legal interest ("benefit of suit") in challenging Y's entitlement to a share in the distribution of the deposited funds. If X successfully disputed Y's claim (e.g., by proving it was fictitious, as alleged), X's own distributable share from the ¥20 million deposit could increase, based on the continuing efficacy of its provisional attachment for the Loan Claim.

Understanding the "Same Basis of Claim" (請求の基礎の同一性 - seikyū no kiso no dōitsusei)

This doctrine is pivotal for understanding the relationship between provisional remedies and the main lawsuit in Japan. It allows for necessary flexibility.

- "Rights Identity Theory" vs. "Claim Basis Theory": The lower courts in this case had implicitly adopted a strict "rights identity theory" (権利同一説 - kenri dōitsu setsu), which demands that the exact legal claim stated as the preserved right in the provisional order must be the one validated in the main lawsuit for the provisional order to retain its effect. The Supreme Court, by contrast, explicitly endorsed the more flexible "claim basis theory" (請求基礎説 - seikyū kiso setsu).

- Rationale for the "Claim Basis Theory": As articulated by the Supreme Court and supporting legal commentary, this theory recognizes the urgent nature of provisional applications. Creditors often lack the time for perfect legal formulation of their claims at that stage. If different legal claims arise from substantially the same underlying factual dispute, the debtor is not unfairly surprised by a later refinement or alternative pleading in the main lawsuit, and the core protective purpose of the initial provisional attachment can still be served. It avoids penalizing creditors for initial imperfections in pleading, especially when the underlying facts supporting both the initially stated preserved claim and the ultimately successful claim largely overlap. Moreover, if the claims share the same basis, the creditor could typically amend their claim in the main lawsuit or in preservation objection proceedings to align the preserved right with the ultimately successful cause of action, making a denial of the provisional attachment's continued effect overly formalistic.

- Criteria for Determining "Same Basis of Claim": While the Supreme Court in this specific judgment focused on the "encompassing" nature of the factual circumstances, legal commentary discusses various potential criteria for assessing whether claims share the "same basis." Some scholars emphasize the identity of the "social dispute or underlying interest" being litigated. Others, and this Supreme Court decision appears to lean this way, focus on the commonality of the material facts (主要事実 - shuyō jijitsu) and the evidence required to prove them. The more overlap there is in the core factual allegations and the necessary proof, the more likely the claims are to be considered as having the "same basis." The exact degree of commonality required may continue to be refined in future jurisprudence.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's February 23, 2012, decision is a significant affirmation of the "claim basis theory" in the context of provisional attachments. It establishes that a provisional attachment can remain effective to secure a creditor's recovery even if the claim ultimately validated in the main lawsuit is not identically formulated to the "preserved claim" stated in the initial provisional attachment order, provided both claims arise from the "same basis of claim." This approach injects a degree of necessary flexibility into the system, acknowledging the urgent and preliminary nature of provisional remedy applications. It ensures that creditors are not unduly penalized for initial imperfections in legal formulation when the underlying factual grievance remains consistent and is ultimately vindicated. This ruling has important practical implications for how creditors frame their "preserved claims" when seeking provisional attachments and for how courts will assess the continuing validity and scope of such attachments as the main litigation unfolds and claims are potentially refined or pursued on alternative legal grounds rooted in the same core facts.