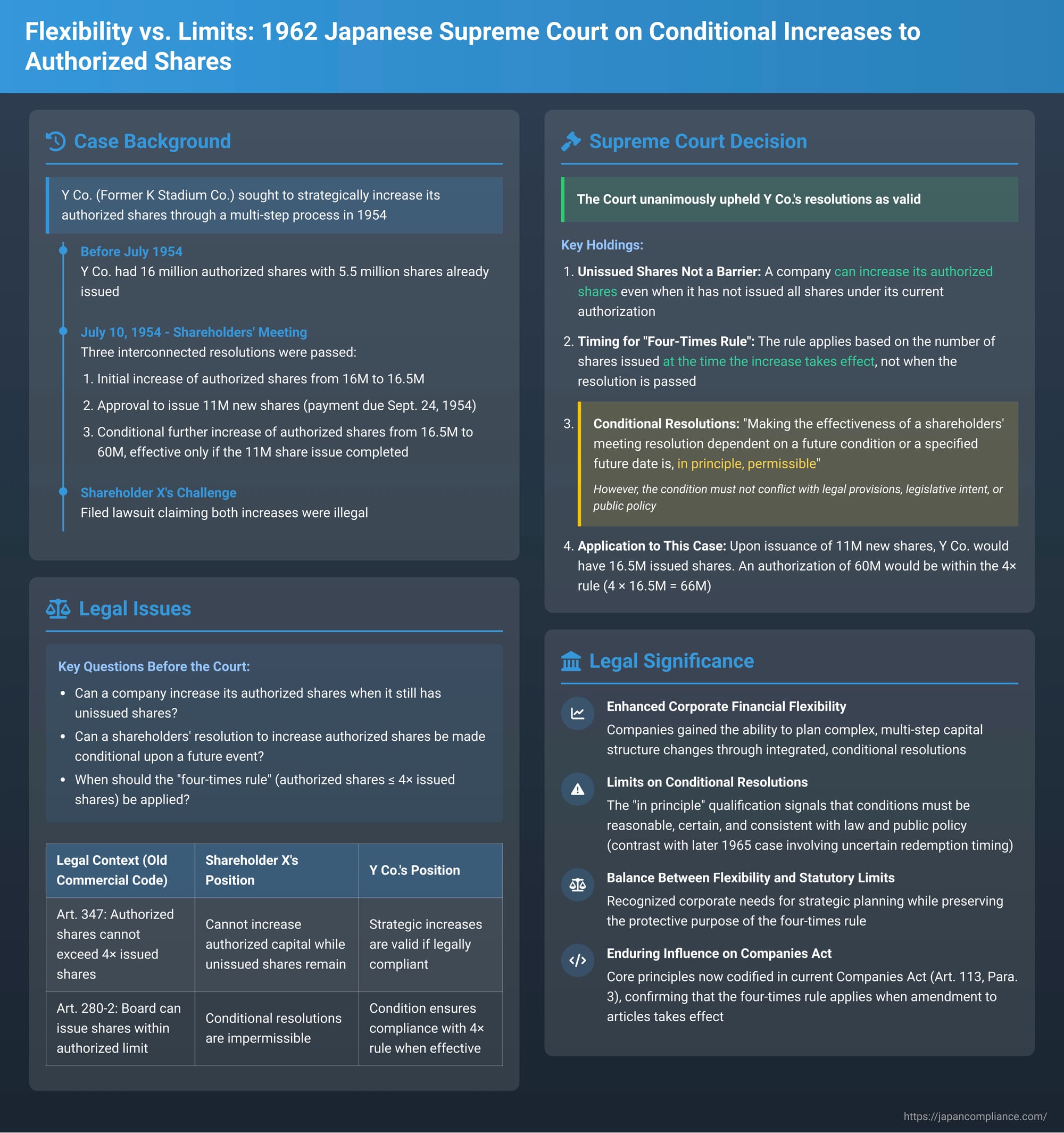

Flexibility vs. Limits: 1962 Japanese Supreme Court on Conditional Increases to Authorized Shares

Date of Judgment: March 8, 1962

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

A company's capital structure is a cornerstone of its financial health and growth potential. Two key concepts in this structure are "authorized shares" – the maximum number of shares a company is permitted to issue as stated in its articles of incorporation – and "issued shares" – the number of shares actually held by shareholders. Companies often need to increase their authorized share capital to pave the way for future share issuances, whether for raising capital, acquisitions, or employee incentives.

This raises several important legal questions: Can a company increase its authorized share limit if it hasn't yet issued all the shares currently permitted under its existing authorization? Furthermore, can such an increase in authorized shares be made conditional upon a future event, such as the successful completion of a new share offering? These questions were central to a significant decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on March 8, 1962.

The Legal Framework of the Time: Japan's Old Commercial Code

The case was decided under Japan's then-prevailing Commercial Code, which contained several relevant provisions:

- Board Authority for New Share Issues: Article 280-2 of the Code generally empowered the board of directors to make decisions regarding the issuance of new shares, provided these were within the total number of shares authorized by the company's articles of incorporation. This was intended to give companies flexibility in raising capital according to economic conditions.

- The "Four-Times Rule": Article 347 of the Code stipulated a crucial limitation: the total number of shares a company was authorized to issue could not be increased to an amount exceeding four times the total number of its already issued shares. This rule aimed to prevent excessive dilution of existing shareholders' interests by limiting the company's ability to issue a disproportionately large number of new shares relative to its current issued base.

Facts of the Y Co. Case

The defendant, Y Co. (formerly K Stadium Co.), had an authorized share capital of 16 million shares, with 5.5 million shares already issued and outstanding. On July 10, 1954, Y Co.'s shareholders' meeting passed a series of interconnected resolutions concerning its share capital:

- Initial Increase in Authorized Shares: The shareholders approved an initial, relatively small increase in the company's total authorized shares from 16 million to 16.5 million shares.

- Approval of a New Share Issue: The meeting then approved the issuance of 11 million new shares. The payment date for these new shares was set for September 24, 1954. If successfully issued, these 11 million shares, added to the existing 5.5 million issued shares, would bring Y Co.'s total issued shares to 16.5 million.

- Conditional Further Increase in Authorized Shares: Crucially, the shareholders also resolved to further increase the company's total authorized shares from 16.5 million to 60 million shares. However, this significant increase was explicitly made conditional upon the successful issuance and payment of the 11 million new shares detailed in the second resolution.

A shareholder of Y Co., Mr. X (F.H. in the judgment), challenged the legality of these resolutions. X argued, among other points, that:

- It was impermissible for Y Co. to increase its authorized share capital while it still had unissued shares remaining under its then-current authorization of 16 million shares.

- Making the larger increase in authorized shares (to 60 million) conditional upon a future new share issue (the "conditional resolution" or 条件付決議 - jōken-tsuki ketsugi) was an illegal corporate action.

The Supreme Court's Decision of March 8, 1962

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, dismissed the shareholder's appeal, upholding the validity of Y Co.'s resolutions.

Increasing Authorized Shares Despite Existing Unissued Shares

The Court first addressed the argument that authorized shares could not be increased if the company had not yet issued all shares under its current limit. It affirmed that a company can indeed increase its total number of authorized shares even if unissued shares remain under its previous authorization. The Court reasoned that the purpose of having a framework for authorized shares is to provide companies with the flexibility to meet future capital requirements efficiently. Restricting increases until all currently authorized shares are issued would unduly hamper this flexibility.

Timing for the Application of the "Four-Times Rule"

A critical clarification provided by the Court concerned the application of the "four-times rule" under Article 347 of the old Commercial Code. The rule stated that authorized shares could not exceed four times the issued shares. The question was, at what point should the number of "issued shares" be determined for this calculation?

The Supreme Court ruled that the reference point for the number of issued shares is not the number of shares issued at the time the shareholders' meeting passes the resolution to increase authorized capital. Instead, it is the number of shares that are issued and outstanding at the time the increase in the total number of authorized shares actually takes effect. (It's worth noting, as the PDF commentary highlights, that this principle is now explicitly codified in Article 113, Paragraph 3 of Japan's current Companies Act, which specifies the reference point as "when the amendment to the articles of incorporation takes effect" ).

Validity of Conditional Resolutions

The most significant aspect of the judgment was its pronouncement on conditional resolutions. The Supreme Court established a general principle that making the effectiveness of a shareholders' meeting resolution dependent on a future condition or a specified future date is, in principle, permissible. This permissibility is subject to the crucial proviso that such a condition must not conflict with any specific legal provisions, the underlying legislative intent, or jōri (a concept encompassing public policy, reason, and the sound order of society).

Applying the Principles to Y Co.'s Conditional Increase

The Court then applied these principles to the specific facts of Y Co.'s resolutions:

- The condition for the major increase in authorized shares (to 60 million) was the successful issuance of the 11 million new shares.

- Upon the issuance of these 11 million shares, Y Co.'s total issued share count would rise to 16.5 million (5.5 million existing + 11 million new).

- At that point, an authorized share capital of 60 million shares would be comfortably within the "four-times rule" limit, as four times 16.5 million issued shares is 66 million shares.

- The conditional nature of the resolution thus ensured that the increase to 60 million authorized shares would only become effective when the company's issued share base had expanded sufficiently to support it under the 4x rule.

The Supreme Court found no violation of Article 347 or any other legal provision or principle in this arrangement. The conditional resolution was deemed valid.

Analysis and Implications

The 1962 Supreme Court decision provided important clarifications and significantly enhanced the flexibility available to Japanese companies in managing their capital structures.

- Enhanced Corporate Financial Flexibility: The ruling empowered companies to engage in more dynamic and forward-looking capital planning. They could align increases in their authorized share capital with specific, anticipated corporate actions like large-scale new share offerings, without having to wait for those offerings to be completed before seeking shareholder approval for the necessary expansion of authorized shares.

- The "In Principle" Qualification: The Court's use of the phrase "in principle" when affirming the permissibility of conditional resolutions is noteworthy. It signals that this is not an unlimited green light; such conditions must always be scrutinized to ensure they do not contravene the law, legislative intent, or broader principles of public policy and reasonableness.

- Certainty and Proximity of the Condition: The PDF commentary accompanying this case points out that in this 1962 instance, the condition precedent (the issuance of 11 million new shares) was clearly defined, and the payment date for these shares was set for the near future (September 24, 1954, just over two months after the July 10, 1954 shareholders' meeting). This relative certainty and proximity likely contributed to the Court's finding that the condition was acceptable.

- Contrast with Uncertain or Remote Conditions: The importance of the nature of the condition is underscored by a subsequent Supreme Court case from 1965 (mentioned in the PDF commentary). In that later case, a resolution to increase authorized shares was made contingent on a more uncertain and potentially remote event (the redemption of certain redeemable shares, the timing of which might not have been fixed). The Court found that particular conditional resolution to be invalid, suggesting that highly uncertain or indefinitely postponed conditions might not meet the standard of reasonableness or adherence to legislative intent.

Relevance Today Under the Japanese Companies Act

While this case was decided under the old Commercial Code, its underlying principles continue to have relevance under Japan's current Companies Act:

- The principle regarding the timing for applying the four-times rule (or similar regulatory ceilings on authorized capital relative to issued capital) is now more explicitly defined in the Companies Act, reflecting the Supreme Court's earlier reasoning.

- The general concept that shareholder resolutions can be made conditional, subject to conformity with law and public policy, remains a practical aspect of corporate law. Modern corporate transactions are often complex and involve multiple interdependent steps, making conditional approvals a useful tool.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1962 decision in the Y Co. case was a pivotal moment in Japanese corporate law, affirming the ability of companies to strategically increase their authorized share capital through conditional resolutions tied to specific corporate events like new share issuances. It clarified that the "four-times rule" for authorized shares should be applied based on the number of shares issued at the time the increase in authorization becomes effective, not when the resolution is merely passed.

While granting companies significant flexibility in capital management, the ruling also, through its "in principle" language and when viewed alongside later case law, underscored that such conditions must be clear, reasonable, and consistent with legal and public policy norms. The decision masterfully balanced the need for dynamic corporate finance with the maintenance of essential regulatory safeguards.