Japan’s New Copyright Flexibilities for AI, Education & Libraries: From Article 30-4 to SARTRAS

TL;DR

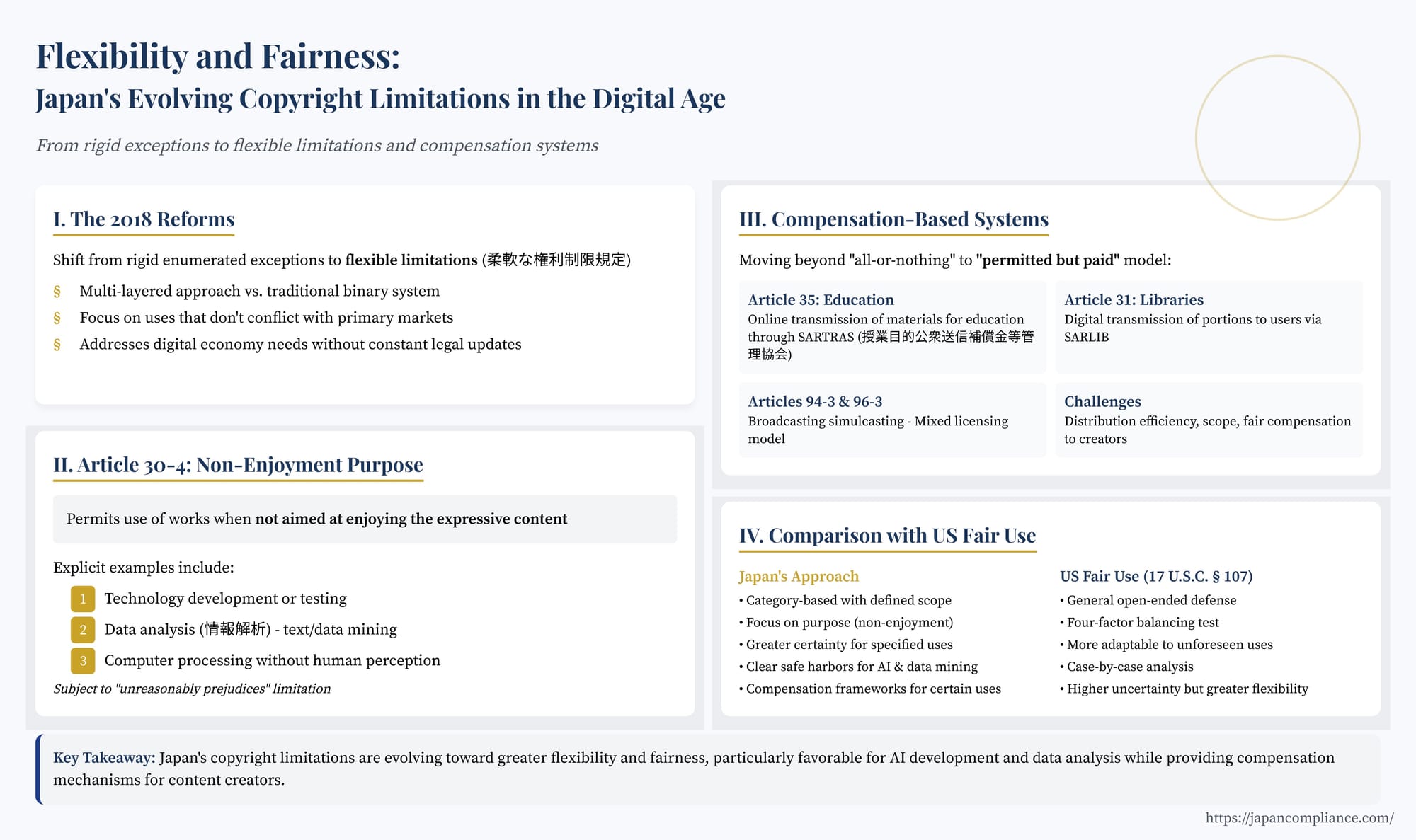

Japan has moved from rigid, enumerated copyright exceptions to a hybrid model: broad “non-enjoyment” uses (Article 30-4) legalise AI training and data mining, while new statutory-license schemes compensate right-holders for online teaching, library e-delivery and broadcaster simulcasts. Staying compliant means knowing where free use ends and payment-based permissions begin.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Adapting Copyright to Digital Realities

- The 2018 Reforms: A Shift Towards “Flexible Limitations”

- Article 30-4: The “Non-Enjoyment Purpose” Exception

- Article 47-5: Facilitating Information Location and Analysis Services

- Article 47-4: Incidental Inclusion

- Comparison with US Fair Use

- Diversifying Approaches: Beyond All-or-Nothing Compensation Systems

- Article 35: Educational Uses and SARTRAS

- Article 31: Library Digital Transmission Services

- Articles 94-3 & 96-3: Broadcasting and Online Simulcasting

- Significance and Challenges of Compensation Systems

- Ongoing Issues and Future Considerations

- Conclusion: Navigating a Landscape in Transition

Introduction: Adapting Copyright to Digital Realities

Copyright law worldwide faces the persistent challenge of adapting principles conceived for analogue media to the realities of the digital, networked environment. Uses of copyrighted works that were unimaginable decades ago – large-scale data analysis for AI training, incidental inclusion in user-generated content, online delivery of educational materials, ubiquitous search engine indexing – are now commonplace. Balancing the legitimate interests of copyright holders with the need to foster innovation, enable access to information, and accommodate new forms of expression requires continuous adjustments to the legal framework.

Japan, like many civil law countries, traditionally approached limitations and exceptions to copyright through a system of specific, enumerated carve-outs in its Copyright Act (著作権法 - Chosakuken Hō). Unlike the broad, flexible "fair use" doctrine found in the United States (17 U.S.C. § 107), Japan historically lacked a general clause allowing courts to permit unforeseen uses based on fairness principles. While providing legal certainty for defined uses, this approach struggled to keep pace with rapid technological advancements, potentially chilling innovation and creating legal uncertainty for beneficial new uses not explicitly covered by an exception.

Recognizing these limitations, Japan has undertaken significant reforms over the past decade, particularly culminating in major amendments in 2018 (effective 2019). These reforms reflect two key trends: first, a deliberate move towards incorporating greater flexibility into the system of limitations, aiming to accommodate new digital uses without requiring constant legislative updates; and second, a growing diversification of approaches beyond the simple binary of full copyright liability versus completely free use, notably through the introduction of statutory license systems involving compensation for certain permitted uses. Understanding these shifts is vital for businesses navigating the use of copyrighted content in Japan's increasingly digital landscape.

The 2018 Reforms: A Shift Towards "Flexible Limitations"

Driven by concerns that the existing rigid structure was inadequate for the digital age, Japan's Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters began advocating for reforms, including exploring a "Japanese-style fair use" concept, as early as 2008. After initial, less comprehensive amendments in 2012, a more ambitious reform package was enacted in 2018. This didn't adopt a US-style general fair use clause but instead introduced several "flexible limitation provisions" (柔軟な権利制限規定 - jūnan na kenri seigen kitei) designed with a "multi-layered" approach.

The core idea was to create broader categories of exceptions for uses that generally don't conflict with the primary market for copyrighted works, particularly those not aimed at the "enjoyment" of the work's expressive content.

Article 30-4: The "Non-Enjoyment Purpose" Exception

Perhaps the most impactful and widely discussed of the 2018 amendments is Article 30-4. This provision permits the exploitation of a copyrighted work, by any means necessary, if the purpose is not to enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in the work (its aesthetic or creative content). It explicitly lists three non-exhaustive examples of such non-enjoyment purposes:

- Use in technology development or testing.

- Use in data analysis (情報解析 - jōhō kaiseki), defined as extracting, comparing, classifying, or statistically analyzing constituent elements from large numbers of works or data.

- Use in computer information processing that does not involve human perception of the work's expression (excluding simple execution of software code).

This article was explicitly designed to facilitate activities crucial in the digital economy, most notably text and data mining (TDM) and the training of artificial intelligence (AI) models. By allowing the use of copyrighted works as input data for analysis and machine learning without requiring permission, provided the aim isn't the enjoyment of the works themselves, Japan created what some consider one of the world's most AI-friendly copyright environments.

However, Article 30-4 contains a crucial limitation: the exception does not apply if the act "unreasonably prejudices the interests of the copyright owner in light of the nature or purpose of the work or the circumstances of the exploitation" (the "Article 30-4 Proviso"). The interpretation of this proviso is key. Government guidelines and reports suggest factors to consider include whether the use competes directly with the original work's market or harms potential licensing markets. For instance:

- Reproducing works specifically for creating a database intended for information analysis (e.g., an AI training dataset) might be permissible under Article 30-4.

- However, creating and selling a database composed primarily of copyrighted works intended for human viewing or enjoyment (like an image database for appreciation) would likely "unreasonably prejudice" the copyright holders' interests and fall outside the exception.

- Similarly, intentionally using copyrighted works to train an AI specifically to generate outputs that closely mimic the creative expression of those input works (not just the underlying style) might be seen as crossing the line into enjoyment and prejudicing the original creators' market.

While Article 30-4 provides significant latitude for AI development, the exact boundaries set by the proviso remain largely untested in Japanese courts. Ongoing discussions involve balancing AI innovation with creators' rights, with some industries advocating for licensing frameworks or technical measures alongside the statutory exception.

Article 47-5: Facilitating Information Location and Analysis Services

Complementing Article 30-4, Article 47-5 addresses the use of works in specific types of online services. It permits necessary exploitation (like reproduction or public transmission) for providing services that facilitate locating information online (like search engine indexing) or analyzing information (like plagiarism detection software or market analysis tools), provided it's within technically feasible limits and, again, does not unreasonably prejudice the copyright owner's interests. This provides a clearer legal basis for the background operations of search engines and similar online information services that need to process vast amounts of copyrighted content.

Article 47-4: Incidental Inclusion

This provision allows for the minor, incidental inclusion of copyrighted works (e.g., music playing in the background of a street recording, art visible in a photograph of an event) when creating a separate, primary work, provided the included work is subsidiary and its inclusion doesn't unreasonably prejudice the rights holder. This addresses common situations in audio-visual recordings and broadcasts.

Comparison with US Fair Use

Japan's "flexible limitations" differ structurally from the US fair use doctrine. US fair use (17 U.S.C. § 107) provides a general, open-ended defense based on a four-factor balancing test: (1) purpose and character of the use, (2) nature of the copyrighted work, (3) amount and substantiality used, and (4) effect on the potential market.

- Certainty vs. Adaptability: Japan's approach offers greater legal certainty for the specified categories (like data analysis under Art. 30-4 or search indexing under Art. 47-5). Businesses engaging in these activities have a clearer safe harbor than under the often unpredictable case-by-case analysis of US fair use. However, the US system is inherently more adaptable to entirely new technologies or unforeseen uses not fitting neatly into Japan's defined categories.

- Focus: Japan's Article 30-4 primarily hinges on the purpose (non-enjoyment), whereas US fair use involves a broader balancing act where market effect often plays a decisive role.

While some observers argue Japan's system isn't a true "fair use" equivalent due to its categorical nature, it represents a pragmatic attempt to provide both flexibility for digital innovation and predictability for stakeholders within a civil law framework. The emphasis on non-enjoyment uses under Article 30-4, in particular, offers significant advantages for AI and data-driven businesses compared to navigating the fair use analysis in the US for similar activities.

Diversifying Approaches: Beyond All-or-Nothing Compensation Systems

A second major trend in recent Japanese copyright reform is the move away from the traditional "all-or-nothing" outcome – where a use is either fully infringing (requiring permission) or entirely permitted under an exception (often without payment). Recognizing that certain socially beneficial uses might still impact rights holders' markets, Japan has increasingly adopted statutory license systems that permit specific uses without prior permission but require the user to pay compensation to rights holders. This reflects an approach closer to some European models, aiming for both access and remuneration.

Article 35: Educational Uses and SARTRAS

Educational institutions traditionally enjoyed exceptions for limited reproduction of works for face-to-face teaching. The rise of online learning and ICT in education highlighted the need for broader permissions covering digital transmission. The 2018 Copyright Act amendments significantly revised Article 35 to address this.

- Expanded Scope: The revised Article 35(1) allows educational institutions (non-profit) to reproduce, publicly transmit (including online streaming or making materials available on demand), and publicly present copyrighted works to the extent necessary for lessons, without prior permission.

- Compensation Requirement: Crucially, Article 35(2) mandates that educational institutions engaging in such public transmission must pay "a reasonable amount of compensation" to the copyright owners.

- Collective Management: To manage this system efficiently, the law provides for a single, government-designated collective management organization (CMO) to collect and distribute this compensation. The Society for the Administration of Remuneration for Public Transmission for School Lessons (SARTRAS, 授業目的公衆送信補償金等管理協会) was designated for this purpose. Schools pay an annual lump-sum fee (calculated based on student numbers and type of institution) to SARTRAS, which then distributes the funds to relevant rights holder CMOs (e.g., for music, literature, visual arts). This system, operational since April 2021 (after a free introductory year in FY2020 due to the pandemic), aims to simplify rights clearance for widespread online educational use while ensuring creators are compensated.

Article 31: Library Digital Transmission Services

Similar pressures arose for libraries during the COVID-19 pandemic, when physical access was restricted. While libraries could provide photocopies of portions of works for research purposes (Art. 31(1)(i)), digital transmission was not permitted.

- 2021 Amendment: The 2021 amendments (effective June 2023 for this part) expanded Article 31 to allow designated libraries to transmit digital copies of portions of works directly to individual users for research purposes via email or other secure methods.

- Compensation System: Like the educational use expansion, this new library transmission service is subject to a compensation requirement (Art. 31(5)). A designated CMO (一般社団法人図書館等公衆送信補償金管理協会 - SARLIB) has been established to manage the collection and distribution of these fees, which libraries offering the service will need to pay. This aims to balance enhanced remote access to library resources with the interests of authors and publishers.

- NDL Exception: Separately, the National Diet Library has broader permissions for digitizing its collection and transmitting out-of-print or otherwise unavailable materials to libraries and, since 2022, directly to individuals.

Articles 94-3 & 96-3: Broadcasting and Online Simulcasting

Broadcasters faced significant hurdles clearing rights, particularly neighboring rights held by performers and phonogram producers, for the online simulcasting or archiving of programs containing commercial music. Obtaining individual licenses for every track was often impractical.

- 2021 Amendments: Addressing this, the 2021 amendments introduced a new mechanism (Articles 94-3 and 96-3). For performances and phonograms already managed by designated CMOs providing broad licenses, broadcasters still need those licenses (maintaining the existing collective licensing framework). However, for works not covered by such broad collective management (e.g., performers or labels not represented by the main CMOs), broadcasters can now transmit them as part of their programs online without prior permission, provided they pay compensation through a designated CMO. This "mixed model" aims to facilitate online transmission while ensuring unrepresented rights holders receive remuneration.

Significance and Challenges of Compensation Systems

The increasing use of compensation-based limitations represents a significant shift in Japanese copyright policy. It acknowledges that facilitating access and use in the digital age sometimes requires limiting exclusive rights, but attempts to mitigate the economic impact on creators through mandatory remuneration.

However, challenges remain:

- Scope: Currently, compensation is generally only applied to newly permitted uses (like online transmission for education). Pre-existing free uses under exceptions (like photocopying in schools or libraries) remain uncompensated, a point of contention for some rights holder groups.

- Collection and Distribution: Efficiently and fairly distributing collected compensation, especially when dealing with vast numbers of works and potentially unrepresented rights holders, is a complex task for CMOs like SARTRAS and SARLIB. Ensuring accurate reporting and minimizing administrative costs are ongoing challenges.

- Beneficiaries: The compensation is typically channeled through CMOs representing copyright owners or neighboring rights holders (publishers, record labels, performer organizations). Whether sufficient funds ultimately reach the individual authors and performers is a recurring question in collective management systems worldwide.

Ongoing Issues and Future Considerations

Despite recent reforms, Japan's copyright law continues to evolve. Key areas to watch include:

- Interpreting "Unreasonably Prejudicial": The application of the crucial proviso in Articles 30-4 and 47-5 ("unreasonably prejudices the interests of the copyright owner") will be refined through court decisions and administrative practice. Its interpretation will significantly impact the scope of permitted uses for AI, data analysis, and online services.

- Emerging Technologies: Applying existing rules to newer technologies like the Metaverse or increasingly sophisticated generative AI presents fresh challenges. Questions arise about authorship of AI creations, liability for infringement by AI outputs, and the scope of limitations in virtual environments.

- Compensation Systems: The operation and potential expansion of compensation-based limitations will likely continue to be debated, focusing on fairness, efficiency, and scope.

- International Context: Japan actively participates in international discussions on copyright harmonization, balancing domestic policy goals with global trends and treaty obligations.

Conclusion: Navigating a Landscape in Transition

Japan's copyright landscape has undergone a significant transformation, moving from a rigid system of enumerated exceptions towards a more nuanced framework incorporating flexibility and diverse approaches like compensation-based limitations. The 2018 amendments, particularly Article 30-4, have positioned Japan favorably for AI development and data analysis, offering clearer permissions than available under fair use in some contexts. Simultaneously, the introduction of statutory compensation systems for educational and library uses reflects a commitment to balancing access with remuneration for creators.

For businesses operating in Japan, this evolving landscape requires careful attention. Leveraging the flexible exceptions for non-enjoyment purposes can unlock opportunities in data analytics and AI. However, understanding the precise scope of these exceptions, particularly the "unreasonably prejudicial" limitation, is crucial to avoid infringement. Furthermore, businesses involved in education, library services, or online broadcasting must navigate the new compensation requirements. Staying informed about ongoing interpretations, emerging case law, and potential future legislative adjustments will be essential for ensuring copyright compliance and effectively utilizing content in Japan's digital economy.