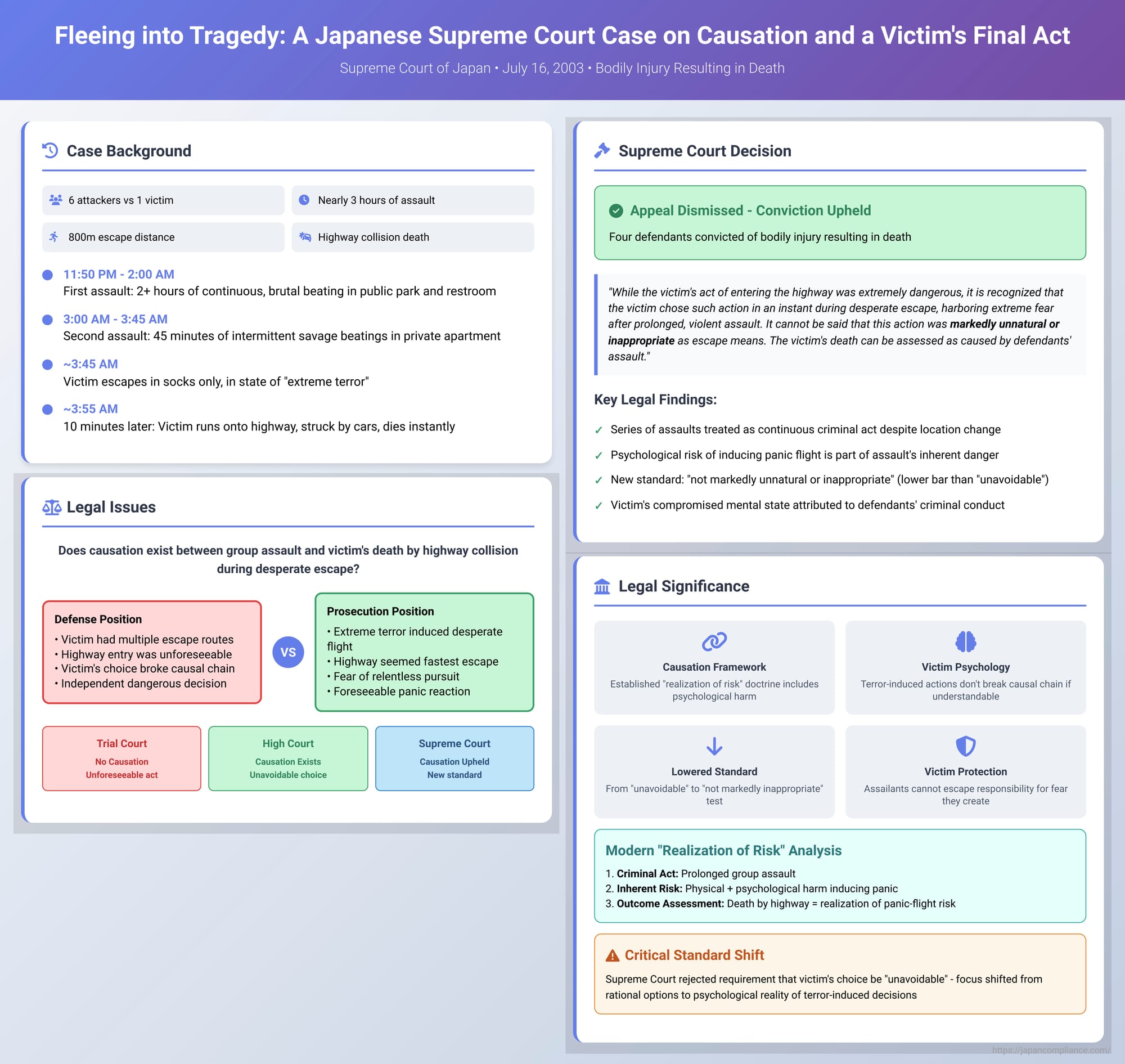

Fleeing into Tragedy: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Causation and a Victim's Final Act

Decision Date: July 16, 2003

Case Name: Bodily Injury Resulting in Death

In criminal law, the line between an assailant's action and a victim's death can sometimes be blurred by a final, desperate choice. Imagine a person, brutalized and terrified, who flees their attackers. In their panic, they make a decision—to run into traffic, to jump from a height—that proves fatal. Does the legal responsibility for their death lie with the attackers who created the terror, or with the victim whose own act was the immediate cause of death?

This harrowing question lies at the heart of a landmark 2003 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case, involving a prolonged and vicious group assault, forced the judiciary to confront the limits of causation. The Court’s ultimate ruling provides a profound insight into how Japanese law evaluates the link between criminal violence and a victim’s subsequent, self-endangering actions, establishing a standard that hinges not on the logic of the victim’s choice, but on the terror that inspired it.

The Facts of the Case: An Ordeal of Violence

The events that led to the victim’s death were a protracted nightmare of brutality. The facts, as established by the courts, paint a grim picture of a group attack carried out in two phases by six individuals, including the four defendants who appealed to the Supreme Court.

The First Assault:

The ordeal began late at night, around 11:50 PM. In a public park and its adjacent public restroom, the group of six launched a relentless attack on the victim. For approximately two hours and ten minutes, until around 2:00 AM, they subjected him to a continuous and exceptionally violent beating.

The Second Assault:

The violence did not end there. The assailants then moved the victim to a private apartment. There, from roughly 3:00 AM to 3:45 AM, the assault resumed. For another 45 minutes, the victim endured intermittent but similarly savage beatings.

In total, the victim was subjected to nearly three hours of brutal group violence.

The Escape and the Final Moments:

At some point during the second assault, the victim saw an opportunity. He managed to escape from the apartment, fleeing in only his socks. The court records emphasize that he was in a state of "extreme terror."

Approximately 10 minutes after his escape, the victim’s desperate flight came to a tragic end. About 800 meters from the apartment, he ran onto a highway. He was immediately struck by a moving car and then run over by a following vehicle, resulting in his death.

A Tale of Two Courts: Diverging Views on Causation

The path of the case through the Japanese legal system revealed a deep judicial divide on the central issue of causation (inga-kankei). The trial court and the appellate court arrived at diametrically opposed conclusions.

The Trial Court (First Instance): Causation Denied

The initial court that heard the case acquitted the defendants of the charge of bodily injury resulting in death. While acknowledging the horrific nature of the assault, the judges broke the causal link between the violence and the death.

Their reasoning focused on the victim's agency. They argued that after escaping the apartment, the victim had numerous options and alternative routes. His decision to enter a high-speed highway, they concluded, was an unforeseeable and abnormal act. It was not, in the legal terminology of the time, a "realization of the risk" created by the assault. In the court's view, the victim's own dangerous and unexpected choice was the true cause of his death, severing the defendants’ responsibility.

The High Court (Second Instance): Causation Affirmed

The prosecution appealed, and the High Court reversed the trial court's decision, finding the defendants guilty. The appellate judges viewed the facts through a different lens, one that focused intensely on the victim's state of mind.

The High Court highlighted several key factors:

- The Proximity: The short distance (around 800 meters) and brief time (about 10 minutes) between the escape and the fatal incident suggested a continuous, frantic flight.

- The Psychological State: The victim was in a state of "extreme terror" after hours of relentless violence.

- The Threat of Pursuit: Given the nature of the six-on-one group assault, it was reasonable for the victim to assume his attackers would be pursuing him relentlessly.

From this perspective, the victim’s choice was not abnormal. The High Court reasoned that, in his terrified state and desperate to escape a determined pursuit, entering the highway may have instantly appeared to be the most effective, or perhaps only, way to get away. The court characterized the choice as "unavoidable" under the circumstances and therefore not an "abnormal" intervening event. The causal chain was intact.

Four of the defendants, convicted by the High Court, appealed to the final arbiter of Japanese law: the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

The Supreme Court sided with the High Court, upholding the convictions. The justices' concise but powerful reasoning established a clear and lasting legal standard for such cases.

The Court stated:

"While the victim's act of entering the highway in an attempt to escape was, in itself, an extremely dangerous act, it is recognized that the victim chose such an action in an instant during a desperate attempt to escape, harboring extreme fear towards the defendants after being subjected to a prolonged, violent, and persistent assault. It cannot be said that this action was markedly unnatural or inappropriate as a means of escaping from the defendants' assault. This being so, it can be assessed that the victim's death upon entering the highway was caused by the defendants' assault."

The Court affirmed that the causal link between the assault and the death was unbroken. The core of the decision lies in that crucial, carefully worded standard: "not markedly unnatural or inappropriate."

Unpacking the Legal Doctrine: "The Realization of Risk"

To fully grasp the significance of the Supreme Court's ruling, one must understand the dominant legal framework for causation in Japan: the doctrine of "realization of risk" (kiken no genjitsuka). This theory proposes a structured analysis:

- Identify the Criminal Act: Pinpoint the specific conduct of the defendant that constitutes the crime (e.g., the assault).

- Define the Inherent Risk: Analyze the specific dangers or risks created by that criminal act.

- Assess the Outcome: Determine if the actual result that occurred was a manifestation, or "realization," of that inherent risk.

In this case, the "criminal act" was not just a single punch, but the entire "series of assaults." Despite the change in location and the one-hour break between the two phases of the attack, the courts treated it as one continuous event, united by the defendants' singular, ongoing intent to brutalize the victim.

The crucial debate was over the second and third steps. What was the "risk" created by this prolonged assault, and was death-by-highway a "realization" of it? The risk was not merely that the victim might die from the physical blows (e.g., from shock or internal injuries). The assault also created a profound psychological risk: the risk of inducing such extreme fear and panic that the victim would be driven to take life-threatening actions to escape.

The Supreme Court affirmed that this psychological risk was indeed part of the danger created by the defendants. The victim’s death was a tragic realization of that very risk.

Lowering the Bar: From "Unavoidable" to "Not Inappropriate"

The true innovation in the Supreme Court's decision lies in the standard it set for evaluating the victim's final action. The disagreement between the lower courts and the Supreme Court was effectively a debate about how compromised a victim's free will must be to maintain the chain of causation.

- The trial court set an extremely high bar, suggesting that unless the victim had virtually no other choice, his action was his own responsibility. This view implicitly champions a strong principle of personal agency, which can only be overridden by overwhelming coercion.

- The High Court, while finding for the prosecution, also used a high standard, describing the victim's choice as "unavoidable." This still implies a near-total elimination of other viable options.

The Supreme Court deliberately lowered this bar. By asking only whether the action was "not markedly unnatural or inappropriate," the Court shifted the focus. The question was no longer "Did the victim have any other choice?" Instead, it became "Was the victim's choice understandable, given the extreme terror and duress created by the defendants?"

This is a profound shift. It acknowledges the reality of human psychology under extreme threat. A person fleeing for their life after hours of torture is not a rational actor weighing pros and cons. They are a bundle of instinct and terror. Their actions may not be logical or even the "best" choice in hindsight, but they are a direct product of the criminal's actions. The Supreme Court declared that as long as the victim's desperate choice is not "markedly" or "grossly" unnatural, it does not sever the causal tie.

This approach prevents assailants from escaping responsibility by arguing that their victim should have had the presence of mind to choose a safer escape route. The responsibility for the victim's compromised mental state, and the panicked decisions that flow from it, remains with those who created it.

A Critical View: Is the Doctrine Just a Label?

Some legal commentators have questioned whether the elegant "realization of risk" framework is truly the engine of judicial reasoning, or simply a label applied after the fact to justify a more intuitive conclusion. A more direct analysis might be to simply assess the "influence or contribution" of the defendant's act on the final result.

From this perspective, the analysis is more straightforward: The defendants' vicious and prolonged assault directly "induced" the victim's intervening act of fleeing onto the highway. The defendants' violent conduct exerted such an overwhelming psychological influence on the victim that his subsequent actions cannot be seen as independent. Therefore, the influence of the initial assault was never broken, and causation is established. While the "realization of risk" language provides a sophisticated structure, this more direct assessment of influence may more accurately reflect the core judgment being made.

Conclusion: The Enduring Weight of Fear

The Supreme Court's 2003 decision is a cornerstone of modern Japanese criminal law on causation. It clarifies that the chain of responsibility is not easily broken by the panicked, and even dangerous, choices a victim makes while trying to save their own life. By establishing the "not markedly unnatural or inappropriate" standard, the court affirmed that creating terror is a culpable act with far-reaching consequences. It sends a clear message that the law will hold perpetrators accountable not only for the direct physical results of their violence, but also for the foreseeable and tragic consequences of the fear they inflict.