Flawed Building Permit, Owner's Loss: Japanese Supreme Court on State Liability and Architect Fraud

Date of Judgment: March 26, 2013

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

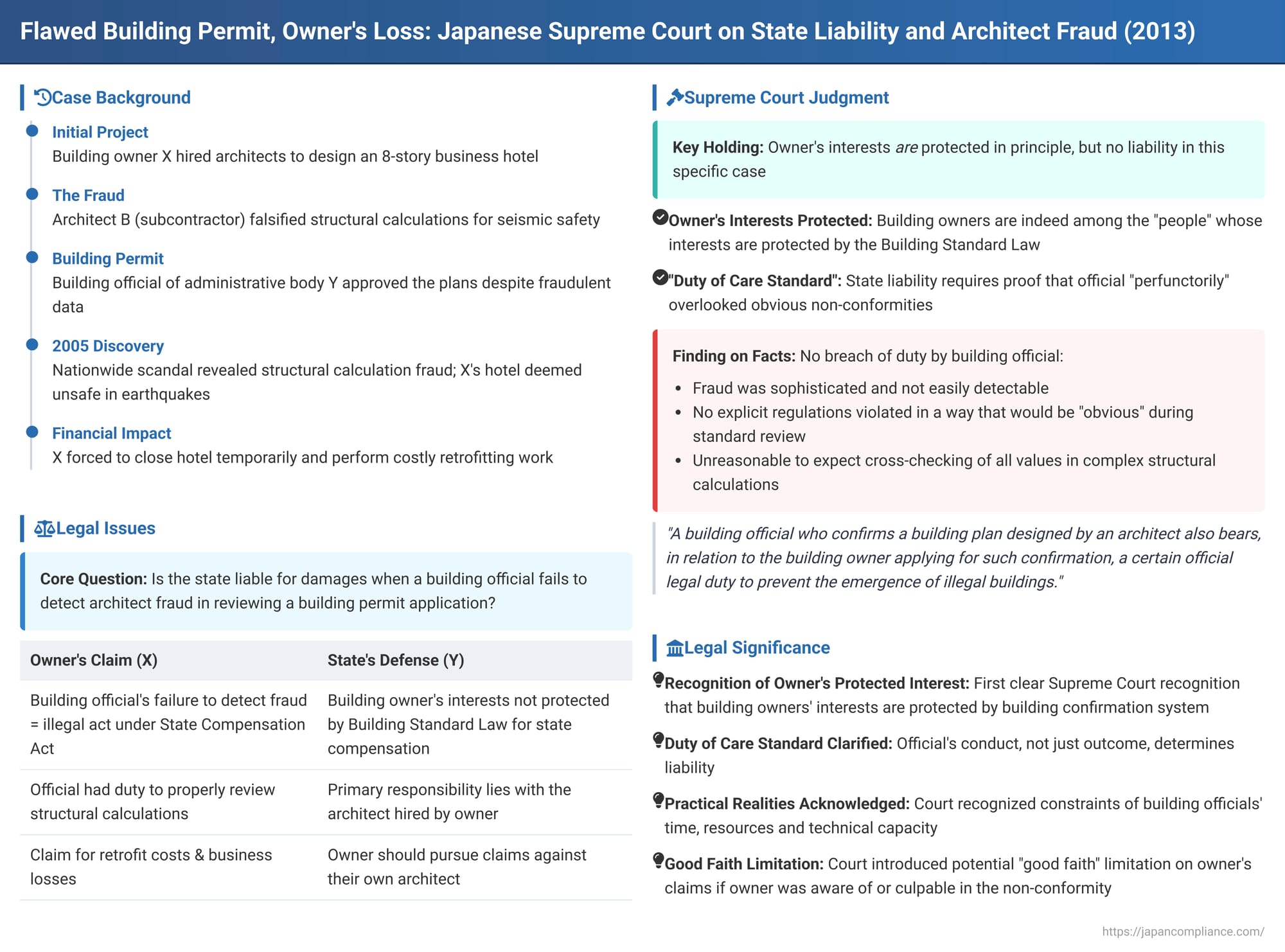

On March 26, 2013, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment addressing the complex issue of state compensation liability when a building owner suffers financial loss due to a flawed building confirmation (often referred to as a building permit) that failed to detect structural calculation fraud committed by an architect hired by the owner themselves. This case, involving a business hotel project, required the Court to clarify whether a building owner's own interests are protected by the building confirmation system for the purposes of a state compensation claim, and what standard of care is expected from public building officials in reviewing architect-designed plans. The Supreme Court affirmed that a building owner's interest in a lawfully confirmed building can indeed be a basis for a state compensation claim, but it also set a high bar for establishing the building official's liability, focusing on a "duty of care" standard that scrutinizes the official's conduct rather than merely the flawed outcome of the permit.

I. The Faulty Foundation: A Hotel Built on Deception

The case originated from the construction of a business hotel that was later discovered to have severe structural deficiencies due to fraudulent design calculations.

The Project and Key Parties:

The plaintiff, X, was the owner and developer of a planned eight-story business hotel. Under Japan's Building Standard Law (BSL) and the Architect Law, a building project of this nature and scale required its design to be undertaken by a first-class registered architect (ikkyū kenchikushi). Accordingly, X engaged the services of Architect A, a first-class architect, to design the hotel. It appears that Architect A, in turn, subcontracted or otherwise delegated the critical task of preparing the structural engineering calculations for the building to another first-class architect, Architect B. It was Architect B who ultimately committed the fraudulent calculations. The defendant, Y, was the administrative body (such as a city or prefecture) that employed the public building official (kenchiku shuji) responsible for issuing the building confirmation.

The Building Confirmation Process and Hidden Fraud:

X, acting through Architect A as their agent, formally applied to the building official employed by Y for a "building confirmation." This confirmation, mandated by Article 6 of the BSL, is a crucial administrative permit that verifies that the proposed building plans comply with all relevant building codes, safety standards, and other regulations before construction work can legally commence.

The application package submitted to the building official included detailed structural calculation documents. These documents, which were prepared by Architect B, purported to demonstrate the seismic safety and structural integrity of the proposed hotel design. The calculations were presented as having been performed using a structural analysis software program that had been certified by the relevant government Ministry (the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, or its predecessors). However, these submitted documents contained deliberate and serious fraudulent calculations related to the building's seismic resistance. Specific examples of this fraud, as later uncovered, included:

- The mismodeling of shear walls that contained openings (holed shear walls), which are critical components for a building's resistance to earthquake forces. These were allegedly modeled as if they were solid, more robust shear walls, thereby significantly overstating their structural strength and capacity.

- The falsification of calculations related to the building's stiffness ratios between different floors. Proper stiffness ratios are essential for ensuring a building responds predictably and safely to seismic forces. The fraudulent calculations made the building appear more uniformly resistant to earthquake forces than it actually was.

- The use of incorrect (specifically, significantly understated) shear force values in the design calculations for essential load-bearing walls. This occurred despite the fact that the raw output from the certified computer program used for the analysis reportedly indicated much higher, and therefore more critical, actual shear forces that these walls would need to withstand. The particular structural calculation program used in this instance had a standard specification where these crucial shear force values needed to be manually inputted by the architect for certain types of shear wall design checks, and it was at this manual input stage that the falsification of data apparently occurred.

Issuance of the Building Permit, Construction, and Subsequent Discovery of Fraud:

The building official reviewed the application documents, including the fraudulent structural calculations, and subsequently issued the building confirmation, effectively greenlighting the project. X then proceeded with the construction of the hotel, which was completed after it also passed the required interim and final inspections conducted by the building authorities.

Several years later, in 2005, a major nationwide scandal erupted in Japan involving widespread instances of structural calculation fraud committed by various architects across numerous building projects. Architect B was implicated in this scandal. Investigations into X's hotel, prompted by this broader crisis, revealed that its structural calculations were indeed fraudulent. The defendant administrative body (Y) subsequently conducted its own assessments and determined that X's newly built hotel, due to these fraudulent calculations and resulting structural deficiencies, did not meet the requisite seismic safety standards and was at a significant risk of collapse in the event of a major earthquake. Consequently, Y formally requested X to prepare a comprehensive retrofitting plan and to carry out extensive structural reinforcement work on the hotel to bring it up to code. X complied with this official request, thereby incurring substantial costs for the remedial construction work. X also suffered significant business losses due to the hotel's necessary temporary closure while the retrofitting was underway.

II. The Legal Battle for Compensation: Owner vs. State

Following the discovery of the fraud and the costly rectification work, X sought to recover these losses by suing the administrative body responsible for the building official who had issued the original, flawed building confirmation.

X's Claim Against the State for Damages:

X filed a lawsuit against Y (the administrative body that employed the building official) seeking monetary damages. This claim was based on Article 1 of Japan's State Compensation Act, which provides for state liability when public officials, in the exercise of public power, illegally cause damage to citizens, either intentionally or negligently. X argued that the building official's failure to detect the architect's blatant fraud during the review of the building confirmation application constituted an illegal act (or omission) of a public official, for which the State (through its administrative body Y) was liable. The damages claimed by X included the substantial costs of the retrofitting work, lost profits resulting from the hotel's temporary closure, and other related expenses.

A Key and Contentious Feature of the Case:

A distinctive and legally challenging feature of this case was that the building owner (X)—who had themselves originally hired (or whose primary architect, A, had hired) the architect (Architect B) ultimately responsible for perpetrating the fraudulent design—was now seeking compensation from the state. The claim was predicated on the argument that the state's building official had failed to catch the fraud committed by X's own (indirectly) chosen design professional. This raised a central legal question: does the State Compensation Act protect the interests of an applicant building owner in such circumstances, or is the owner expected to bear the primary risk of their own architect's misconduct? In other words, to what extent does the building official's duty extend to protecting the applicant themselves from the errors or fraud of the applicant's own agents?

Lower Court Rulings Against the Building Owner:

The lower courts were not sympathetic to X's claim against the state:

- District Court (Kyoto District Court): The Kyoto District Court dismissed X's claim for damages. While it acknowledged, in principle, that ensuring the safety of a building's occupants could be an interest protected under state compensation law, it adopted a restrictive view concerning the building owner's own direct property or financial interests in relation to the permitting authority. The District Court reasoned that any direct financial loss suffered by the owner due to their architect's fraud was primarily a matter to be resolved through private law claims (e.g., for breach of contract or professional negligence) by X against the culpable architect or the construction company involved in the project. The court seemed to imply that the Building Standard Law's primary purpose, from the perspective of state liability, was to ensure public safety and protect the interests of third parties (like neighbors or future users of the building), and that the applicant building owner's own economic interests in the value or compliance of their investment were not directly within the scope of protection offered by the BSL in a way that would ground a state compensation claim against the permitting authority for a flawed permit issued to that owner.

- High Court (Osaka High Court): On appeal, the Osaka High Court also dismissed X's claim. It largely echoed the District Court's reasoning, concluding that the building owner's property rights, in this specific context, were not encompassed within the protective scope of the building laws in a manner that would allow a state compensation claim against the permitting authority for having issued a confirmation based on the owner's (via their architect's) flawed application.

X's Appeal to the Supreme Court:

X, being dissatisfied with these consistent rulings against their claim in the lower courts, filed a petition for acceptance of appeal with the Supreme Court of Japan. The Supreme Court granted this petition, agreeing to hear the case.

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment: Affirming a Protectable Interest for the Owner but Ultimately Denying Liability on the Specific Facts

The Supreme Court of Japan, in its carefully reasoned decision of March 26, 2013, ultimately dismissed X's appeal. This meant that X's claim for damages against the state failed. However, the Court's reasoning in arriving at this conclusion was nuanced and, on a key point of principle regarding the protectability of a building owner's interests, differed significantly from the more restrictive views taken by the lower courts.

A. The Building Owner's Interest IS, in Principle, Protected by the Building Confirmation System:

- The Supreme Court began its analysis by referencing the overarching purpose of Japan's Building Standard Law (BSL). Article 1 of the BSL states that its objective is to protect the "life, health, and property of the people" (kokumin) by establishing minimum standards for building structures, safety, and related matters.

- The Court acknowledged the legal framework established by the Architect Law, under which the primary responsibility for ensuring the safety and compliance of a building's design rests with the qualified architect who prepares that design. It also recognized that when a building owner formally applies for a building confirmation from a public building official, they are, in effect, seeking official verification that the plans prepared by their chosen architect comply with all applicable building codes and regulations.

- However, in a crucial departure from the reasoning of the lower courts, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected the narrow view that the building owner's own interests are somehow excluded from the BSL's protective ambit, particularly in the context of potential state compensation liability. The Supreme Court stated that "it is difficult to construe that an individual citizen who is a building owner is not included among the 'people' (kokumin) referred to in Article 1 [of the BSL], and that the interests of the building owner related to the building they construct are not subject to protection under said Act."

- The Court further reasoned that "the purpose of the building confirmation system includes the protection of the interests of individual citizens obtained through the prevention of the emergence of buildings that violate building standard-related regulations, and it can be said that the protection of the building owner's interests is also included therein."

- Based on this broader understanding of the BSL's protective scope, the Supreme Court concluded: "it is appropriate to understand that a building official who confirms a building plan designed by an architect also bears, in relation to the building owner applying for such confirmation, a certain official legal duty to prevent the emergence of illegal buildings." This was a highly significant finding, as it established, as a matter of principle, that building owners could potentially have a valid claim for state compensation if this duty owed to them by the building official was breached, leading to damage.

B. The Standard for Determining "Illegality" of a Building Confirmation for State Compensation Purposes:

Having established that a building official owes a certain duty to the applicant building owner, the Supreme Court then articulated the specific standard for determining when a building official's issuance of a flawed confirmation would be deemed "illegal" for the purposes of imposing state compensation liability under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act.

- The Court stated: "A building confirmation by a building official concerning such a plan is to be deemed illegal for the application of Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act if, for example, when the content of the said plan does not conform to explicitly stipulated requirements in the building standard-related regulations, an error in the descriptive matters of the application documents is clear, and the person in charge of examining said matters should naturally have checked whether it conformed with other descriptive content or materials but such checking was not done, etc., and it is recognized that as a result of the building official failing to exercise the care that should ordinarily be paid in their official duties when confirming the descriptions in the application documents and thereby perfunctorily (manzen to) overlooking the non-conformity, they performed a building confirmation for the said plan."

- This standard clearly adopts and applies the "duty of care standard" (shokumu kōi kijun-setsu). This standard had been previously established by the Supreme Court in other contexts, such as the 1993 tax reassessment ruling (discussed in case g213). It means that a mere error or incorrectness in the building confirmation is not, by itself, sufficient to establish state liability. Instead, there must be a demonstrated failure on the part of the building official to exercise the level of ordinary professional care and diligence expected in their position, leading to a "perfunctory" oversight of a flaw that should have been discoverable through such ordinary care.

C. A Potential Limitation on an Owner's Claim: The Principle of Good Faith (Shingi-soku):

The Supreme Court introduced an important caveat or potential limitation on a building owner's ability to claim damages, even if the building confirmation were found to be "illegal" under the "duty of care" standard articulated above.

- The Court stated: "it cannot be denied that there may be cases where the building owner who is the applicant for the building confirmation is deemed unable to claim damages under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act on the grounds of the illegality of the building confirmation related to the said plan, by reason that asserting the illegality of the building confirmation done by the building official in response to their own application is recognized as contrary to the principle of good faith (shingi-soku), etc., in light of various circumstances such as the presence or absence of the building owner's awareness of or degree of culpability regarding the non-conformity, the nature and content of the damage suffered by the building owner, the degree of the building official's breach of the duty of care or the content of their awareness, and other various factors."

- This passage suggests that if the building owner themselves had some knowledge of the design flaws, or was somehow contributorily negligent or otherwise culpable in relation to the fraudulent design submitted in their name (even if the fraud was primarily by their hired architect), then allowing that owner to later claim damages from the state for the building official's failure to detect the fraud might be considered contrary to principles of good faith and fair dealing (a concept roughly analogous to equitable doctrines like "clean hands" or estoppel in common law systems).

D. Application of the "Duty of Care" Standard to the Specific Facts of X's Case – No Breach of Duty Found by the Building Official:

The Supreme Court then meticulously examined the specific instances of structural calculation fraud that had occurred in X's hotel plans to determine whether the building official, in failing to detect them, had breached the ordinary duty of care expected of such an official.

- Regarding the Mismodeling of Holed Shear Walls: The Court noted that at the time this building confirmation was issued, the Building Standard Law and its implementing regulations did not contain specific, explicit rules dictating precisely how such holed shear walls should be digitally modeled for structural calculation purposes. Therefore, the Court found, the plan submitted by X's architect, while potentially flawed from a sophisticated engineering best-practice standpoint due to the mismodeling, was not in clear, explicit violation of any affirmatively stated regulatory requirement regarding modeling techniques.

- Regarding the Falsified Stiffness Ratios: The Court acknowledged that the application documents might have shown fewer shear walls on the first floor of the hotel compared to the upper floors. However, it found that this visual discrepancy alone did not make it "immediately obvious" that the claimed stiffness ratio for the first floor (which, on paper, met the minimum 0.6 requirement set by the code) was impossible or necessarily incorrect. Other structural design elements of the columns and the overall framing of the building could theoretically influence the actual stiffness achieved. The Supreme Court concluded that the error regarding the stiffness ratios was not "apparent on the face of the application documents" in such a way that a building official, through ordinary review, would have been alerted to a definite problem without undertaking a complete re-calculation or an in-depth independent re-analysis of the submitted structural data. Such a detailed re-analysis, the Court implied, was beyond the scope of the ordinary review expected during the confirmation process.

- Regarding the Use of False (Understated) Shear Force Values in Shear Wall Design: The Court directly addressed the critical issue where false (significantly understated) shear force values had been manually inputted into the design calculations for the load-bearing shear walls, instead of the much higher, actual shear forces indicated by the raw output of the certified structural analysis program. The Court considered several practical realities of the building confirmation system at the time: (a) the specific structural calculation program used by Architect B was just one of over 100 different Ministry-certified programs available, each potentially having different features, input methods, and output formats; (b) the output from such sophisticated structural analysis programs is often voluminous and highly technical; and (c) the number of manually inputted numerical values in a complex structural calculation for a multi-story building can be extensive. Given these factors, and particularly considering the relatively short statutory timeframe within which building officials are expected to review and process building confirmation applications (typically 21 days for buildings of this type), the Supreme Court found that it would be unreasonable to expect a building official to "minutely grasp" the specific input requirements and operational details of every single one of the many certified programs, or to "meticulously cross-check every manually inputted numerical value" against all the raw program outputs for consistency and accuracy. The Court concluded that this type of error, while serious, was not "obvious" from a standard, reasonable review of the submitted documents by the building official.

Supreme Court's Conclusion on X's Specific Case:

Based on this detailed analysis of each of the alleged oversights by the building official in reviewing the fraudulent documents, the Supreme Court concluded that "it cannot be recognized that the building official in this case, if they had confirmed the descriptions in the application documents with the care that should ordinarily be paid in their official duties, could have discovered the non-conformity of the plan for the building in question with the building standard-related regulations, and that they perfunctorily overlooked such non-conformity despite that." In other words, the Court found no breach of the ordinary duty of care by the building official. Consequently, it held that the building confirmation, although ultimately based on fraudulent data supplied by X's architect, was not "illegal" for the purposes of imposing liability under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. X's appeal was therefore dismissed, and the claim for damages failed.

IV. Legal Commentary and Analysis: Duty, Protection, and Practical Realities

This 2013 Supreme Court decision has generated considerable legal commentary in Japan, particularly concerning its implications for state liability, the duties of public officials, and the rights of individuals interacting with regulatory systems.

Significance of the Judgment in Clarifying Standards:

- This case emphasizes two main points of significance in this Supreme Court decision. Firstly, it was the first Supreme Court ruling to explicitly clarify that the "duty of care standard" (shokumu kōi kijun-setsu) is the appropriate legal test for determining the "illegality" of a building confirmation when assessing a claim for state compensation. This is important because it means that even for an administrative act like a building confirmation—which might be seen as involving less discretion than other types of permits or licenses—if there is underlying fraud or error in the application that is not caught, the focus for determining state liability is not merely on the fact that the outcome (the issued permit) was flawed. Instead, the focus shifts to the conduct and diligence of the building official who reviewed the application. Liability will only attach if that official failed to meet the expected standard of care.

- Secondly, and perhaps more crucially from the perspective of building owners and developers, the judgment recognized that the building owner's own interests (specifically, their interest in obtaining a safe and legally compliant building through the confirmation process) can be considered as interests that are protected by the building confirmation system for the purposes of a potential state compensation claim. This was a significant departure from, and a rejection of, the more restrictive reasoning adopted by the lower courts in this case. The lower courts had tended to view the Building Standard Law as primarily protecting only the interests of third parties (such as neighbors or future occupants of the building) or general public safety, to the exclusion of the applicant building owner's direct property or financial interests when that owner was suing the permitting authority over a flawed permit that the owner themselves had applied for. The Supreme Court's broader view on this point, in principle, opened the door for building owners to seek state compensation if they could demonstrate a breach of the building official's duty of care owed to them.

The "Duty of Care Standard" (shokumu kōi kijun-setsu) in the Building Confirmation Context:

- The Supreme Court's application of the "duty of care standard" to building confirmations reflects an acknowledgment of the practical realities of modern construction and building administration in Japan. Buildings have become increasingly complex from an architectural and engineering perspective, involving sophisticated designs and intricate calculations. Public building officials, who often operate with limited time and resources, must rely to a significant extent on the professional certifications, detailed plans, and complex calculations provided by qualified professionals, such as first-class registered architects. These architects, in turn, have their own primary legal and ethical duties under Japan's Architect Law to ensure the safety and compliance of their designs.

- Moreover, the Japanese building regulatory system has seen the rise of private designated confirmation and inspection bodies (shitei kakunin kensa kikan). For many projects, these private entities now conduct the primary review and issue building confirmations, with public building officials potentially having a more circumscribed oversight role. These systemic factors inevitably influence the judicially expected level of care and scrutiny from a public building official when they are directly reviewing a confirmation application. The Supreme Court's standard in this case, which focuses on whether an error was "obvious" or "perfunctorily overlooked" through a failure of "ordinary care," appears to take into account these practical limitations and the structured reliance on professional intermediaries.

Protectable Interests (Hogo Rieke-sei) and the Building Owner as an Applicant:

- The Supreme Court's explicit finding that a building owner's interest is, in principle, protected by the building confirmation system for the purposes of a potential state compensation claim is a key jurisprudential takeaway from this decision.

- The trend in modern Japanese administrative law, as indicated by this 2013 judgment and other contemporary cases, is to move away from a strict application of the "reflexive interest" doctrine, particularly if a demonstrable, concrete individual interest is found to have been infringed due to an official's breach of a legally recognized duty. This decision is important for explicitly including the applicant building owner within the ambit of those whose interests are considered to be protected by the building confirmation process, at least for the purpose of potentially founding a state compensation claim if the building official is found to have breached their specific duty of care owed to that owner during the review process. Using the term "protectable interest" (yō hogo rieki sei) is now considered more appropriate and reflective of current legal thinking than the older "reflexive interest" terminology.

The Nuanced Discussion in the Supplementary Opinions:

- It is also noteworthy that the Supreme Court's judgment included several supplementary opinions from the justices who heard the case. These supplementary opinions delved deeper into some of the theoretical underpinnings of the duty of care, particularly concerning the complex question of whether the standard of care owed by the building official might legitimately differ depending on who is claiming damages—for example, whether the duty owed to the building owner (who is the applicant and the architect's client) is the same as, or different from, the duty owed to an unrelated third party who might be subsequently injured by a building collapse due to the same design flaw.

- Justice Tahara's supplementary opinion, for instance, emphasized the "objective" nature of a building confirmation process: it is primarily about ensuring the building's compliance with objective safety standards, not about the personal attributes or status of the applicant. This opinion seemed to suggest that the standard of safety required, and thus the official's duty to verify that standard, should not fundamentally differ based on whether the claimant is the building owner or a third party.

- In contrast, the joint supplementary opinion by Justices Terada and Ohashi suggested that principles from general tort law, which often take into account the specific relationship between the parties and the nature of the interest that has been infringed, could be relevant in determining the scope of the duty of care. They argued that there might indeed be "meaningful differences" in the type of interest held by the building owner (who is not only the applicant but also the client of the architect responsible for the design) compared to an unrelated third party who suffers harm. This difference in position and interest, they posited, could legitimately lead to variations in the content or level of the duty of care owed by the building official to these different categories of potential claimants.

- The majority opinion of the Supreme Court, however, did not need to definitively resolve this nuanced and theoretically challenging debate raised in the supplementary opinions. This was because it found, on the specific facts of X's case, that there was no breach of the building official's ordinary duty of care even when assessed from the perspective of the building owner X. Thus, the question of whether a different or perhaps higher standard of care might have applied if a third party had been the plaintiff and had suffered injury was left open for another day.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's March 26, 2013, decision in this challenging case, involving a building owner's claim for substantial damages due to a flawed building confirmation that failed to detect an architect's deeply embedded structural fraud, provides a critical and nuanced illustration of the Court's approach to state compensation liability in the complex arena of regulatory approvals.

Critically, the Supreme Court affirmed an important principle: a building owner's own interest in receiving a lawful and correct building confirmation is an interest that falls within the protective scope of the Building Standard Law for the purposes of potentially founding a state compensation claim. This finding represented a significant departure from the more restrictive views that had been adopted by the lower courts in this case, and it offers a potential avenue for redress to building owners who suffer harm due to truly egregious failures in the building confirmation process.

However, the Supreme Court also established a notably high bar for successfully pursuing such a claim. It held that state liability would only arise if it could be demonstrated that the building official, in reviewing the application and issuing the confirmation, had failed to exercise the ordinary duty of care expected in their professional position and had "perfunctorily" overlooked clear and readily discoverable non-conformities with building regulations. In this specific instance, due to the sophisticated nature of the architect's fraud, the complexities of modern structural calculation software, and the practical limitations inherent in the administrative review process, the Supreme Court found no such breach of duty by the building official. Consequently, while affirming the owner's theoretical right to claim, it ultimately denied the owner's claim for damages on the facts. The ruling underscores a careful judicial balancing act: on one hand, the need to protect building applicants from clear and culpable administrative failures, and on the other, an acknowledgment of the operational realities and inherent limitations faced by public administrative bodies in a technologically complex world.