Fixed Terms for Public Servants? A Landmark Case on Administrative Act "Riders"

Date of Judgment: April 2, 1963, Third Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan

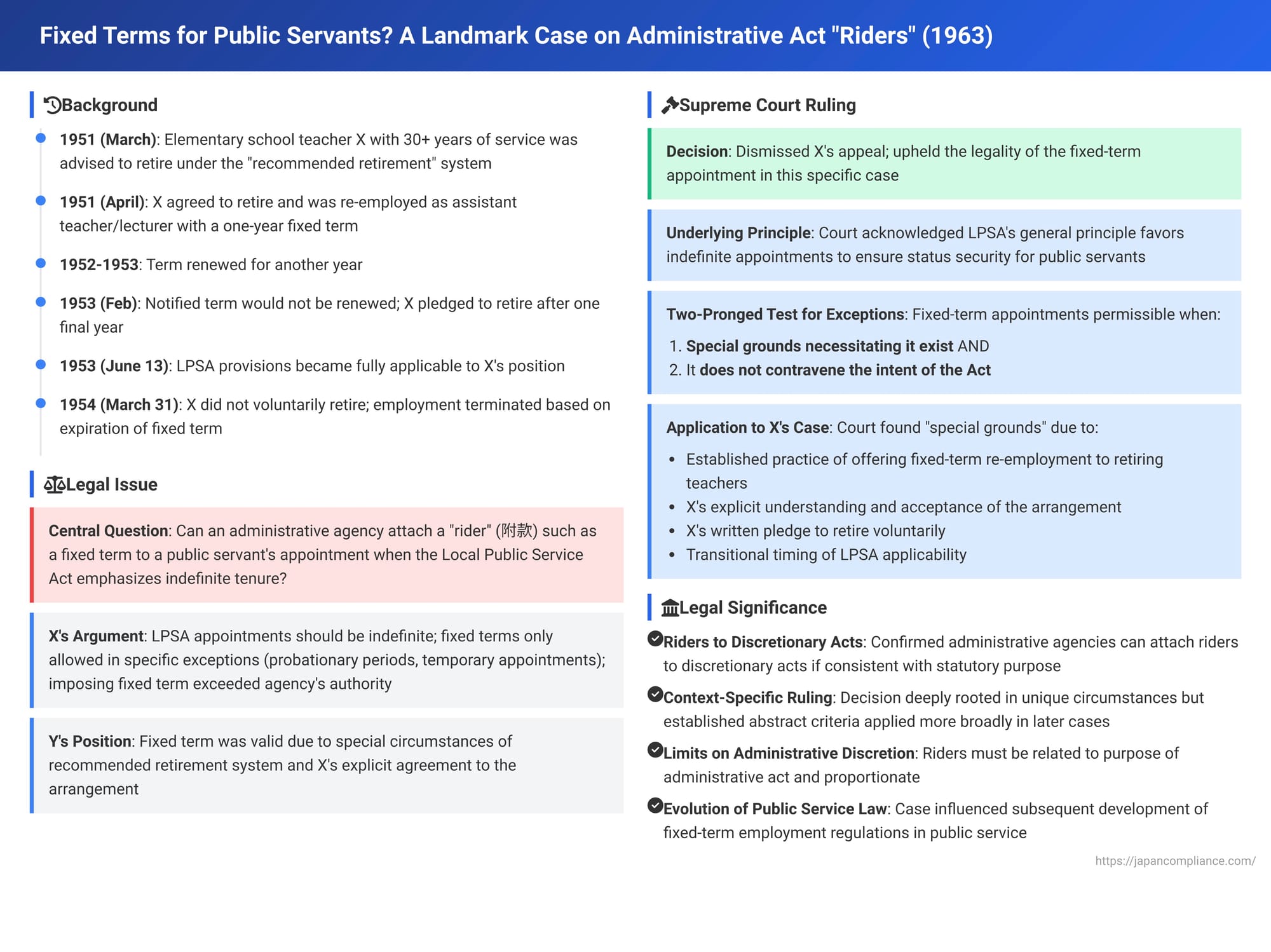

The appointment of public servants in Japan, particularly teachers, has traditionally been based on the principle of indefinite tenure, designed to ensure stability and allow officials to perform their duties without fear of arbitrary dismissal. However, can an administrative agency attach a "rider" (附款 - fukan), such as a fixed term, to an appointment that would normally be indefinite? This question was at the heart of a significant Supreme Court of Japan decision on April 2, 1963. The case explored the permissibility of fixed-term appointments under the Local Public Service Act (LPSA) when no explicit statutory provision allowed for them in regular circumstances, establishing important, albeit context-dependent, principles.

The Factual Background: A Teacher's Retirement and Fixed-Term Re-employment

The appellant, X, had served as an elementary school teacher in Yamagata Prefecture for over 30 years. In March 1951, the Prefectural Board of Education advised X to retire. At that time, there was no mandatory retirement age system for local public servants, including teachers. To facilitate personnel refreshment, a common practice was "recommended retirement" (勧奨退職 - kanshō taishoku). As part of this practice, and to ease the financial transition for retiring teachers who might face hardship, it was customary for the education authorities to offer re-employment as an assistant teacher or lecturer for a limited period, typically one year.

X, after receiving assurances from the Prefectural Board of Education that he would be re-employed on such a fixed-term basis, accepted the recommendation to retire. He officially retired on March 31, 1951. Shortly thereafter, on April 3, 1951, he was appointed as an assistant teacher (his position was later changed to lecturer) at an elementary school in A Village for a one-year term. This fixed-term appointment was renewed for the subsequent academic year.

Around February 1953, the A Village Education Committee, which was the appointing authority, notified X that his term would not be renewed from April 1953 onwards. X pleaded for one more year of employment and, in doing so, submitted a written pledge stating that he would voluntarily retire on March 31, 1954. Based on this, he received a final one-year renewal of his appointment.

A crucial legal development occurred during this final term: on June 13, 1953, the provisions of the Local Public Service Act (LPSA) concerning personnel appointments, including those related to status protection, became fully applicable to municipal employees like X. Previously, X's status as a fixed-term lecturer/assistant teacher might have been viewed differently, possibly more akin to a contractual employment, but from this date, the LPSA's protections theoretically extended to him.

Despite his pledge, X did not voluntarily retire on March 31, 1954. Consequently, the A Village Education Committee issued a disposition terminating his employment as of that date, based on the expiry of his fixed term. X filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of this "retirement disposition," arguing that it was illegal. His primary contention was that, under the LPSA, appointments of regular public employees should, in principle, be without a fixed term, except for specific exceptions like probationary periods or temporary appointments, neither of which applied to his situation. He argued that while the appointing authority might have discretion in deciding whom to appoint, this discretion did not extend to imposing a fixed term on an appointment in a manner contrary to the spirit of the LPSA, which emphasized job security.

The first instance court (Yamagata District Court) and the second instance court (Sendai High Court) both dismissed X's claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court. The appellee in the Supreme Court was the Yamagata Prefectural Personnel Commission (Y).

The Legal Question: The Permissibility of Fixed-Term Appointments under the LPSA

The central legal question was whether a fixed-term appointment for a regular public servant, such as an elementary school teacher, was permissible under the Local Public Service Act, which generally aimed to provide tenure and status security. This involved considering whether attaching a "term" (期限 - kigen), as a type of administrative act "rider" (fukan), to an appointment was lawful in the absence of explicit statutory authorization for such a general practice.

The Supreme Court's Decision of April 2, 1963

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, ultimately finding that the fixed-term appointment in his specific case was permissible.

1. The LPSA's Underlying Principle of Indefinite Tenure

The Court began by acknowledging the general thrust of the LPSA regarding employment terms:

"Regarding whether fixed-term appointment of personnel is permissible under the Local Public Service Act, although there is no specific provision in the Act, considering that the Act adopts a system of conditional employment (probationary period) (see Art. 22(1)), clearly stipulates grounds for dismissal for cause and disciplinary dismissal (see Arts. 28, 29) to guarantee personnel status, and particularly provides for temporary appointments, limiting their requirements and duration (see Art. 22(2)), it should be understood that the Act's underlying principle (建前 - tatemae) is that personnel appointments are to be without a fixed term, just as asserted by the appellant.

2. Permissibility of Fixed-Term Appointments Under Specific Conditions

Despite acknowledging the principle of indefinite tenure, the Court carved out an exception:

"However, since this underlying principle of the Act is intended to guarantee the status of personnel and allow them to devote themselves to their duties with peace of mind, fixed-term appointment of personnel should also be permissible, even without an explicit statutory provision authorizing it, in cases where special grounds necessitating it exist AND it does not contravene the aforementioned intent of the Act.

The Court effectively stated that while indefinite appointments were the norm, fixed-term appointments could be lawful if justified by (a) "special grounds necessitating it" (それを必要とする特段の事由が存し - sore o hitsuyō to suru tokudan no jiyū ga son shi) and (b) the attachment of the term "does not contravene the said intent of the Act" (それが右の趣旨に反しない場合 - sore ga migi no shushi ni hanshinai baai), i.e., it does not unduly undermine the employee's status security or their ability to serve with peace of mind.

3. Application to X's Specific Circumstances

The Court then applied this two-pronged test to the particular facts of X's situation:

The judgment referenced the factual findings of the lower court, which highlighted:

- The prevailing system in Yamagata Prefecture at the time: due to the lack of a mandatory retirement age, "recommended retirement" was used for personnel renewal.

- The established practice of offering one-year fixed-term re-employment as assistant teachers or lecturers to those who retired under this system and faced financial hardship, as a transitional measure.

- X's explicit understanding and acceptance of this arrangement, including his initial agreement to retire in exchange for a one-year fixed-term re-employment, and his later plea for a final one-year extension accompanied by a written pledge to retire voluntarily at its conclusion.

- The legal status of X before the full application of the LPSA's appointment provisions to his municipality from June 13, 1953: "Under the factual circumstances of this case, and also taking into account that X did not have status protection until June 13, 1953... the fixed-term appointment for X cannot be deemed illegal for lacking the aforementioned requirements, even after June 13, 1953.

Based on this unique confluence of factors, the Supreme Court concluded that X's fixed-term appointment, even for the period after the LPSA's employment provisions became fully applicable to him, did not lack the "special grounds" and was not contrary to the "intent of the Act". Thus, the termination of his employment upon the expiry of the agreed term was lawful.

Key Takeaways and Analysis

This 1963 Supreme Court decision, while fact-specific, offers important insights into the judicial treatment of "administrative act riders" (fukan), particularly "terms" or time limits, in the context of public employment.

1. Riders to Discretionary Acts:

The judgment implicitly supports the general principle that if an administrative act (such as a public servant's appointment) involves an element of discretion on the part of the appointing authority, riders may be attached to that act. However, such riders must be consistent with the purpose and spirit of the empowering legislation, even if the statute does not explicitly authorize the specific type of rider in question.

2. "Special Grounds" and "Non-Contravention of Legislative Intent" as Criteria:

The Court articulated a two-part test for the permissibility of fixed-term appointments for regular public servants under the LPSA: the existence of "special grounds necessitating" the fixed term, and a showing that such a term would "not contravene the intent of the Act" (primarily, the protection of status and enabling dedicated service). These criteria, while providing a framework, are inherently abstract and their application depends heavily on the specific facts of each case.

3. A Highly Context-Specific Ruling:

Legal commentators have emphasized that the Supreme Court's decision to uphold X's fixed-term appointment was deeply rooted in the unique historical and factual circumstances of his case. These included the absence of a formal retirement system at the time, the established local practice of using recommended retirement coupled with short-term re-employment as a compassionate measure, X's explicit agreement to this arrangement (including a written pledge to retire), and the phased implementation of the LPSA's full protections. It is therefore argued that the ruling should be understood as a limited and exceptional one, rather than a broad endorsement of fixed-term appointments for regular public servants.

4. Subsequent Interpretation and Broader Application:

Despite the specific context of this 1963 ruling, the commentary notes that because the criteria laid down by the Supreme Court were somewhat abstract, later judicial decisions reportedly cited this case as a precedent to more broadly affirm the legality of fixed-term appointments in other public sector contexts, arguably extending its reach beyond what might have been originally envisaged.

5. General Limits on Administrative Act Riders:

Although not the primary focus of X's challenge in this specific case, the permissibility of administrative act riders is generally subject to further limitations. Riders must typically be related to the purpose of the main administrative act to which they are attached and must be proportionate, meaning they should not impose undue burdens on the affected party or be otherwise unreasonable. This principle was affirmed in other Supreme Court cases, such as one involving conditions attached to a building permit in an urban planning context.

6. Evolution of Public Service Law:

It is important to note, as the commentary points out, that Japanese public service law concerning fixed-term employment has undergone significant evolution since 1963. Notably, amendments to the Local Public Service Act in 2017 (effective April 2020) introduced a new category of "fiscal year appointees" (会計年度任用職員 - kaikei nendo nin'yō shokuin), providing a more explicit statutory framework for certain types of non-permanent public employment. These developments have somewhat diminished the direct day-to-day applicability of this specific 1963 ruling to current public servant appointment practices, but its theoretical value regarding the general permissibility of administrative act riders remains.

Conclusion

The 1963 Supreme Court decision in this teacher's fixed-term appointment case is a significant judgment in the realm of Japanese administrative law concerning "riders" attached to administrative acts. While upholding the underlying principle of the Local Public Service Act that regular public servant appointments should generally be without a fixed term to ensure status security, the Court carved out an exception. It held that fixed-term appointments could be permissible if "special grounds necessitating it exist" and if such terms do "not contravene the intent of the Act." Although the Court's finding was heavily based on the unique factual matrix of the case—particularly the post-retirement re-employment scheme in an era without mandatory retirement—the abstract nature of the criteria it set forth had a lasting influence. The case underscores the judiciary's role in balancing legislative intent, administrative needs, and individual circumstances when assessing the legality of conditions attached to administrative acts.