Fixed-Term or Probation? A Deep Dive into a Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Employment Ruling

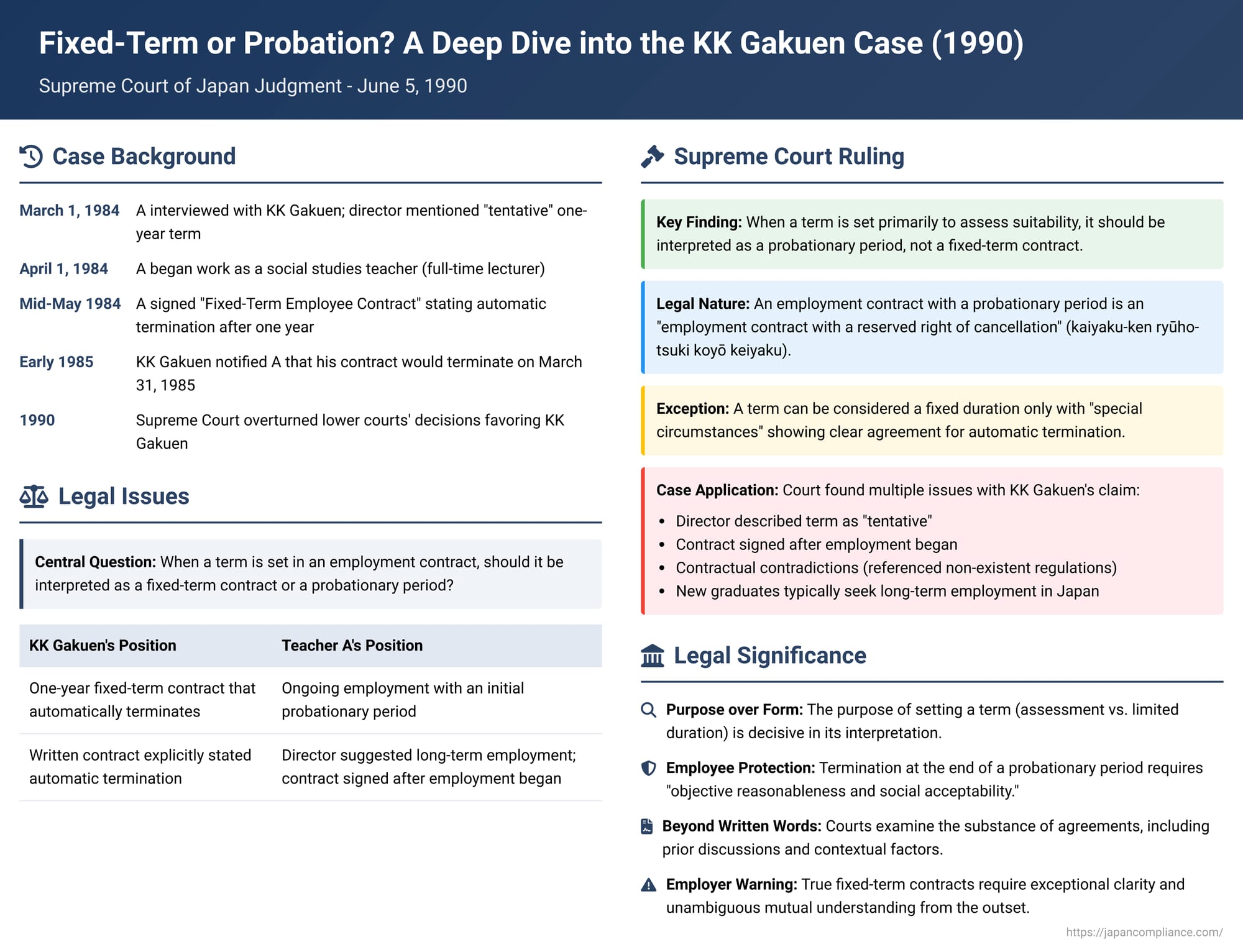

In the complex world of employment law, the distinction between a fixed-term contract and a probationary period carries profound implications for both employers and employees. While a fixed-term contract generally expires automatically at the end of its term, a probationary period often implies an expectation of ongoing employment, with termination requiring more substantial justification. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court judgment delivered on June 5, 1990, in what we will refer to as the K K Gakuen case, grappled with this critical distinction, offering enduring principles for interpreting employment agreements where an initial term is set, ostensibly for assessing an employee's suitability.

The Genesis of the Dispute: The K K Gakuen Case

The case involved a plaintiff, A, and a defendant, K K Gakuen, a school corporation operating a high school. The timeline and key events leading to the legal battle were as follows:

A was hired as a social studies teacher (full-time lecturer) at K K Gakuen's High School, commencing April 1, 1984. The hiring process involved two interviews. During the second interview on March 1, 1984, the director of K K Gakuen explained that A's position would be that of a full-time lecturer, the contract term would "tentatively" be one year from April 1, and a decision on "re-employment" would be made after observing his performance for that year. A was also orally offered the position at this time.

Relying on this offer, A declined a previously secured offer from another institution, School H, where he had been provisionally accepted as a part-time lecturer for a one-year term. On March 5, A submitted a report on his post-employment aspirations, as requested by K K Gakuen. On the same day, he received a general explanation of working hours, salary, and subjects to be taught from the deputy principal and others, which he accepted, thereby formalizing his acceptance of the employment offer. He began his duties on April 1, 1984.

However, in mid-May 1984, A was asked by K K Gakuen to sign a "Fixed-Term Employee Contract." This document, which had been provided to him around April 7, stipulated that A was hired as a full-time lecturer for a fixed one-year term ending March 31, 1985, and that upon the expiry of this term, the employment would automatically terminate without any need for dismissal notice or other notifications. A signed and sealed this document.

Prior to the end of the one-year period, K K Gakuen notified A that his contract would terminate as per the agreement. A contested this, asserting his status as a teacher, and initiated legal proceedings. The court of first instance and the subsequent appellate court both ruled in favor of K K Gakuen, finding that the employment contract was for a fixed one-year term and had legitimately ended upon its expiration. A appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (June 5, 1990)

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the decisions of the lower courts and remanded the case back to the Osaka High Court for further deliberation. The Court's reasoning provided a crucial framework for analyzing such employment scenarios.

The lower court had acknowledged that K K Gakuen's reason for establishing a one-year term was to assess A's suitability, as the school was newly established and needed to hire a large number of teachers simultaneously. A, being new to teaching, required an observation period, and one year was chosen because the academic and school event cycle typically spans a year, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation.

Building on this, the Supreme Court laid out two key principles:

Principle 1: Determining if a Fixed Term is a Probationary Period

The Court stated that when an employer hires a new employee and includes a fixed term in the employment contract, if the purpose and objective of setting that term is to evaluate and judge the employee's suitability, then that term should be construed as a probationary period, not a definitive contract duration. An exception to this would be if "special circumstances" exist, such as a clear and explicit agreement between the parties that the employment contract will automatically and unequivocally terminate upon the expiration of the said term.

Principle 2: The Legal Nature of an Employment Contract with a Probationary Period

Regarding the legal character of an employment contract that includes a probationary period, the Court explained that this must be determined by considering the actual treatment of the employee during the probationary period and the practices related to formal hiring at the end of such a period.

Specifically, if an employee on probation works in the same workplace and performs the same duties as employees who are not on probation, if there is no significant difference in how the employer treats them, and if no procedural steps for re-employment (i.e., creating a new contract for formal, permanent employment) are taken when the probationary period ends, then, in the absence of other special circumstances, such a contract should be understood as an "employment contract with a reserved right of cancellation" (kaiyaku-ken ryūho-tsuki koyō keiyaku).

The exercise of this reserved right of cancellation, the Court clarified, is permissible only when it is objectively reasonable and considered acceptable according to societal norms, viewed in light of the purpose and objectives of reserving such a right. While this standard might allow for a broader scope of dismissal than in an ordinary employment contract without such a reservation, the termination of an employment contract with a probationary period at its conclusion (i.e., the refusal to transition the employee to permanent status) must still meet this test of objective reasonableness and social acceptability.

Application of these Principles to A's Case:

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied these principles to the facts of A's situation, finding several reasons to doubt the lower court's conclusion:

- Ambiguity Surrounding a "Clear Agreement" for Automatic Termination:

The Court noted that the director of K K Gakuen, during the second interview on March 1, 1984, described the one-year contract period as "tentatively" established. Furthermore, A testified that the director had encouraged him to "decline School H and work hard here for 30 or 40 years" and to "not take the public school teacher exams and come to our school." While the lower court had tried to reconcile these statements with a fixed-term contract by suggesting the director hoped A would prove suitable for long-term employment, the Supreme Court questioned whether the director’s statements, if made as A claimed (an issue the lower court had not definitively clarified), were consistent with a strict, legally binding one-year term. The word "re-employment," as used by the director, was also deemed not conclusively indicative of an intention that the contract would automatically end, requiring a completely new contract. These factors created "considerable doubt" as to whether a clear and explicit agreement for automatic termination upon the one-year expiry had been formed between A and K K Gakuen. - Questionable Validity and Relevance of the "Fixed-Term Employee Contract":

Although the written "Fixed-Term Employee Contract" signed by A explicitly stated that employment would automatically cease after one year, the Supreme Court highlighted several problematic aspects:- Timing: A received this document around April 7, 1984, and signed it in mid-May 1984, after the employment relationship had already commenced on April 1, 1984, based on the oral agreement in March.

- Contradictory Clauses: The first article of the contract stated that K K Gakuen needed to hire A on a fixed-term basis for the 1984 academic year due to circumstances related to student and staff numbers. However, the High School had only opened in April 1983. The 1984 academic year was its second year, with only first and second-year students. The full complement of first to third-year students would only be present from the 1985 academic year. This implied an increasing student population and, consequently, a likely need for more staff, not a temporary or limited need for the 1984 academic year. The Court found it improbable that student or staff numbers necessitated hiring A only for that specific year.

- Non-existent Regulations: The second article of the contract stated that A would comply with K K Gakuen's work regulations. However, evidence suggested that these work regulations had not even been created by May 1984 when A signed the contract.

- These points, the Court reasoned, raised doubts as to whether the written contract accurately reflected the true substance and intent of the employment agreement initially formed.

- A's Reasonable Expectation of Continued Employment:

The record showed that A had graduated from University S in Kyoto in March 1983 and completed a correspondence course at University B in March 1984 before being hired by K K Gakuen. The Supreme Court observed that in Japanese society, individuals in such circumstances—recent graduates embarking on their careers—generally seek long-term, stable employment rather than short-term positions. Therefore, A had "understandable reasons" to expect his employment with K K Gakuen to continue beyond the initial year.

The Supreme Court's Conclusion for Remand:

Given these doubts and unresolved issues, the Supreme Court concluded that it was still questionable whether "special circumstances" existed to definitively prove that a clear agreement for automatic termination after one year had been established when the employment contract was formed. The lower court’s decision to treat the one-year period as a definitive contract duration, leading to automatic termination, was therefore deemed an error in the interpretation of employment contract law, based on insufficient deliberation and inadequate reasoning. This error was considered material to the judgment.

Consequently, the Supreme Court quashed the original judgment and remanded the case to the Osaka High Court. The explicit instruction was for the High Court to further examine:

- Whether "special circumstances" could be identified that would justify interpreting the contract as being for a fixed one-year duration.

- If no such special circumstances were found, and if it was appropriate to consider the employment contract as one with a probationary period, and its legal nature as an "employment contract with a reserved right of cancellation," then:

- Whether K K Gakuen's refusal to retain A constituted a permissible exercise of this reserved right of cancellation (i.e., was objectively reasonable and socially acceptable).

Analysis and Broader Implications

The K K Gakuen judgment is a cornerstone in Japanese employment law concerning the interpretation of initial employment terms. Its significance extends beyond the specific facts of the case:

- The Primacy of Purpose in Fixed Terms: The ruling established a critical interpretive guideline: if an employer sets an initial term primarily to assess an employee's suitability, there is a strong presumption that this term functions as a probationary period within a potentially ongoing employment relationship. This presumption can only be rebutted by clear evidence of "special circumstances," most notably an explicit, unambiguous agreement that the contract is strictly for that fixed duration and will automatically terminate. The Court implicitly raised the bar for what constitutes such "special circumstances."

- "Employment Contract with a Reserved Right of Cancellation": This concept (kaiyaku-ken ryūho-tsuki koyō keiyaku) is central. It means that even if an initial period is probationary, the employer retains a right to terminate the employment (or, more accurately, not proceed to a permanent arrangement) at the end of this period. However, this right is not absolute. Its exercise is subject to a test of "objective reasonableness and social acceptability." This offers employees significantly more protection than they would have under a genuinely fixed-term contract that simply expires. The dismissal must be justified, considering the reasons for the probation and the employee's performance or conduct. While potentially a lower threshold for dismissal than for a regular employee who has passed probation, it is far from an unfettered right to dismiss.

- Scrutiny Beyond the Written Word: The Supreme Court demonstrated a willingness to look beyond the literal text of a written contract, especially when its terms conflict with prior oral agreements, the objective circumstances surrounding the employment, or if the contract was presented and signed under conditions that might undermine its status as a fully representative record of the parties' mutual intent (e.g., signing after employment has already commenced). The inconsistencies between the stated reasons in K K Gakuen's contract and the actual operational realities of the school were a key factor.

- Acknowledging Societal Norms and Expectations: The Court's consideration of the general societal expectation in Japan for new graduates to seek stable, long-term employment is noteworthy. This indicates that the employee's reasonable expectations, shaped by broader social contexts, can be a relevant factor in interpreting ambiguous contractual terms.

- Implications for Employers: For employers, the K K Gakuen case underscores the paramount importance of clarity and meticulousness in drafting employment contracts, particularly when an initial period is intended for assessing suitability. If the true intention is for a strictly fixed term that automatically expires without any possibility of continuation, this must be communicated unequivocally and agreed upon explicitly, preferably from the very outset and documented clearly. Any ambiguity, or any actions or statements by the employer that suggest an expectation of longer-term employment contingent on satisfactory performance, could lead a court to interpret the initial term as a probationary period. This, in turn, would subject any decision not to retain the employee to the stricter standards of a reserved right of cancellation. Relying on boilerplate fixed-term contract language, especially if it contradicts the factual context or prior discussions, is a risky approach.

- Evolving Legal Landscape: While the K K Gakuen judgment remains a vital reference, it's important to recognize that Japanese labor law has continued to evolve since 1990. Subsequent legislation, such as the Labor Contract Act, has introduced further rules regarding the renewal of fixed-term contracts, protections against abusive non-renewals, and pathways for conversion to indefinite-term contracts after repeated renewals. These later developments build upon and, in some areas, provide more explicit frameworks for issues that were addressed through judicial interpretation in cases like K K Gakuen. However, the fundamental principle of carefully discerning the true nature of an employment term – whether it's genuinely fixed or probationary – remains a core concern.

Conclusion

The K K Gakuen Supreme Court decision of June 5, 1990, serves as a powerful reminder that the substance of an employment agreement, gleaned from all surrounding circumstances and the manifest intentions of the parties, can often take precedence over the mere form or literal wording of a written document. When an initial employment term is established with the clear purpose of evaluating an employee's fitness for the role, Japanese courts are inclined to view this as a probationary period, affording the employee greater protections against arbitrary non-retention. Employers who wish to implement truly fixed-term contracts for initial assessment periods must do so with exceptional clarity, consistency, and an unambiguous mutual understanding with the employee, lest the arrangement be re-characterized by the courts, significantly altering the conditions under which the employment relationship can be ended.