Fixed-Term Contracts in Japan: Precedent on Non-Renewal

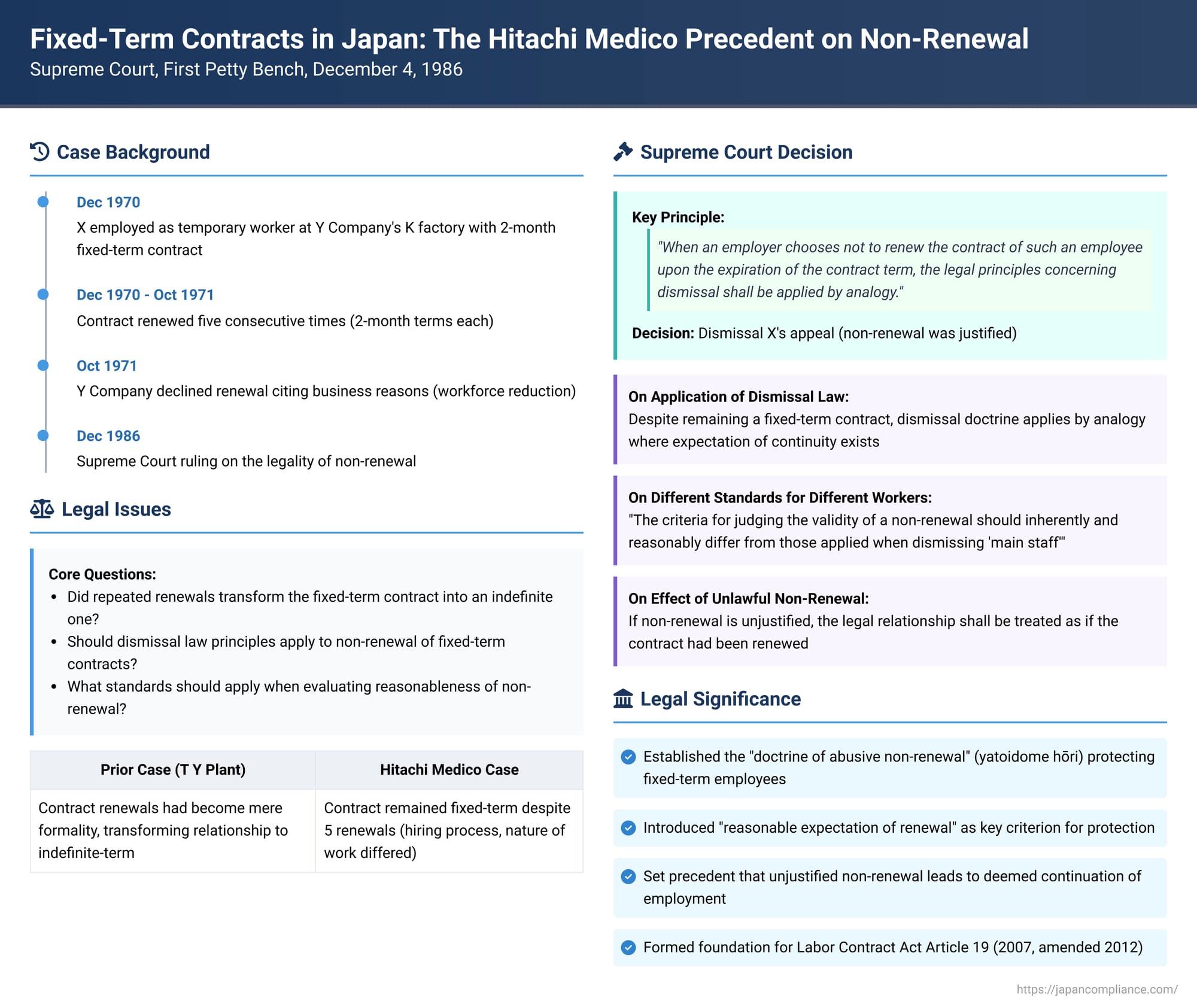

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of December 4, 1986 (Case No. 1981 (O) No. 225: Claim for Confirmation of Labor Contract Existence, etc.)

Appellant: X

Appellee: Y Company

The landscape of employment in Japan, often characterized by the image of lifetime employment, also involves a significant number of fixed-term contract workers. The termination of these contracts, specifically the refusal by an employer to renew a contract upon its expiration (known as yatoidome), has been a contentious area. The Supreme Court judgment of December 4, 1986, stands as a critical precedent in this domain. It significantly shaped the legal principles governing the non-renewal of fixed-term employment contracts, particularly by extending the application of dismissal doctrines by analogy.

Factual Background of the Dispute

The plaintiff, X, was employed as a temporary worker (rinji-in) at the K factory of Y Company. The initial employment contract between X and Y Company was for a fixed period, from December 1, 1970, to December 20, 1970. Following this initial term, the contract, which stipulated a two-month duration, was renewed five consecutive times, extending X's employment until October 20, 1971.

The High Court, whose findings of fact the Supreme Court largely upheld, provided details about Y Company's temporary employee system at the K factory:

- Purpose of the System: The temporary employee system was established to manage fluctuations in employment volume corresponding to changes in business orders due to economic shifts.

- Hiring Process: The hiring procedure for temporary staff was simplified. It did not involve academic or technical skill tests. Instead, hiring decisions were made based on an interview covering aspects like health condition, work history, hobbies, and family structure.

- Retention Rate: Between August and December 1970, Y Company hired 90 temporary workers for its K factory. By October 20, 1971, excluding those who had transitioned to permanent employee status ("main staff" or honkō), only 14 of these temporary workers, including X, remained employed.

- Nature of Work: Temporary workers at the K factory were generally assigned to tasks that were preparatory, simple, or did not demand high precision. X was also engaged in relatively simple work.

- Contract Renewal Procedure: For contract renewals, Y Company would typically confirm the employee's intention to renew approximately one week before the current contract's expiration. The employment period would then be updated on the original labor contract document, and the temporary employee would affix their seal. In X's specific department (the machinery section), if the employee's intent to renew was confirmed, a clerical staff member would stamp the contract on the employee's behalf using a seal kept by the company for payroll receipt purposes. Each of the five renewals of X's contract was formalized through an agreement to conclude a new contract upon the expiration of the preceding one.

In line with a policy to reduce its workforce due to business reasons, Y Company decided to terminate the employment of temporary workers at the K factory, including X. X was notified that his contract would not be renewed upon its expiration on October 20, 1971 (this non-renewal is the subject of the case). X contested this decision, asserting that the non-renewal was unlawful and filed a lawsuit seeking confirmation of his rights under the employment contract, among other claims.

Journey Through the Lower Courts

The Court of First Instance (Chiba District Court, Matsudo Branch, judgment of January 27, 1977) initially ruled in favor of X, upholding his claim.

However, the High Court (Tokyo High Court, judgment of December 16, 1980) overturned this decision. While the High Court acknowledged that legal principles concerning dismissal could be applied by analogy to the non-renewal of X's fixed-term contract, it ultimately concluded that the non-renewal was supported by reasonable grounds. Consequently, X's claim was dismissed, leading X to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision, but its reasoning provided crucial clarifications on the law governing fixed-term contract non-renewals.

1. Nature of the Repeatedly Renewed Contract:

The Court first addressed whether the five renewals had transformed X's fixed-term contract into one of an indefinite term, or created a relationship substantially indistinguishable from that of an indefinite-term contract. It concluded that this was not the case. The Court explicitly distinguished this situation from a prior leading case, the T Y Plant case (Supreme Court, July 22, 1974), stating that the precedent was not suitable for the current case due to differing factual circumstances. In the T Y Plant case, the renewals had become a mere formality, leading to the conclusion that the contract was, in substance, equivalent to an indefinite-term one.

2. Analogous Application of Dismissal Law (Doctrine of Abusive Dismissal):

Despite finding that the contract remained fixed-term, the Supreme Court introduced a pivotal point. It noted that temporary employees at the K factory were not hired for distinctly temporary purposes, such as seasonal labor or the production of specific, one-off items. Instead, their employment relationships carried an expectation of some degree of continuity. Given that X's contract had been renewed five times, the Court ruled:

"When an employer chooses not to renew the contract of such an employee upon the expiration of the contract term, the legal principles concerning dismissal shall be applied by analogy."

This was a significant step. It meant that even if a fixed-term contract did not morph into an indefinite one, the employer’s freedom to simply let it expire was not absolute if there was an expectation of continued employment.

3. Legal Effect of an Unjustified Non-Renewal:

Building on the analogous application of dismissal law, the Court clarified the consequence if a non-renewal were found to be unjustified:

"If an employer refrains from concluding a new contract under factual circumstances where a dismissal would be deemed an abuse of the right to dismiss, contrary to the principle of good faith, or constitute an unfair labor practice, then the legal relationship between the employer and the employee after the expiration of the term shall be treated as if the previous employment contract had been renewed."

This effectively means that an unlawful non-renewal results in a "deemed renewal" of the contract, ensuring continuity of employment under the previous terms.

4. Reasonableness of the Non-Renewal in X's Case:

Having established that dismissal law principles could apply, the Court then examined the reasonableness of Y Company's decision not to renew X's contract. Here, it introduced another crucial distinction:

- Different Standard for Reasonableness: The Court emphasized that the employment of temporary workers like X was premised on short-term, fixed-term contracts entered into via a simplified hiring process, designed to allow for workforce adjustments. Therefore:

"The criteria for judging the validity of a non-renewal should inherently and reasonably differ from those applied when dismissing so-called 'main staff' (honkō), who are hired under indefinite-term contracts with an expectation of, effectively, lifelong employment." - Application to Y Company's Situation: Y Company's K factory operated under an independent accounting system. The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's finding that there were unavoidable business reasons necessitating a personnel reduction at the K factory. Furthermore, there was no scope to transfer surplus temporary personnel to other business departments. In such circumstances, where terminating all temporary staff at the K factory was deemed necessary, the Court stated:

"Even if the company did not, prior to this, implement personnel reduction measures for its indefinite-term employees, such as soliciting voluntary retirements, this cannot be deemed unjust or unreasonable. It is permissible to proceed with the non-renewal of temporary employees before soliciting voluntary retirements from indefinite-term employees."

The Supreme Court concurred with the High Court that Y Company's decision to implement non-renewals for temporary staff at the K factory, including X, was not lacking in rationality given the business conditions in October 1971. Considering Y Company's handling of X's situation, the non-renewal was not found to be an abuse of rights or a violation of the principle of good faith. The circumstances also fell within the K factory's temporary employee work rules, which permitted non-renewal for "business operational reasons."

Thus, X's appeal was dismissed because, although dismissal law applied by analogy, the specific non-renewal was found to be justified under a standard appropriately adjusted for temporary, fixed-term employment.

Significance and Broader Implications of the Judgment

The decision has had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese labor law concerning fixed-term contracts:

- Expansion of the "Doctrine of Abusive Non-Renewal" (Yatoidome Hōri):

Prior to this case, the leading precedent for restricting non-renewals was the T Y Plant case. That case primarily applied dismissal law by analogy when a fixed-term contract, through repeated and pro-forma renewals, had become substantially equivalent to an indefinite-term contract. The judgment significantly broadened this. It established that even if a fixed-term contract does not lose its fixed-term character in substance, a non-renewal can still be unlawful if the employee had a reasonable expectation that the contract would be renewed. This "reasonable expectation" became a key criterion. - Clarification of Legal Consequences:

The judgment clearly articulated that if a non-renewal is deemed unlawful (because it lacks objectively reasonable grounds and is not socially appropriate, analogous to an abusive dismissal), the legal consequence is that the employment contract is treated as if it had been renewed. This provides a concrete remedy for employees facing unjustified non-renewals. - Differentiated Standards for Reasonableness:

The Court acknowledged that the purpose and nature of fixed-term contracts (especially those used for employment adjustment) could justify a different, arguably less stringent, standard for assessing the reasonableness of non-renewal compared to the dismissal of permanent employees. This recognized the employer's need for flexibility, which is often the rationale for using fixed-term contracts. However, this aspect has also been subject to ongoing debate and interpretation, particularly in light of evolving societal norms and legislation aimed at reducing disparities between regular and non-regular employees. - Foundation for Codification in the Labor Contract Act:

The principles developed in the T Y Plant case and refined/expanded in the case laid the crucial groundwork for the eventual codification of the "doctrine of abusive non-renewal" in Japan's Labor Contract Act (LCA), enacted in 2007 and significantly amended concerning fixed-term contracts in 2012.

Specifically, Article 19 of the LCA now stipulates that a non-renewal will not be permitted if it lacks objectively reasonable grounds and is not found to be appropriate in light of generally accepted societal norms, in two types of situations (paraphrased):- LCA Article 19, Item 1: Where the fixed-term contract has been repeatedly renewed and the non-renewal is substantially equivalent to the dismissal of an indefinite-term employee (reflecting the T Y Plant case).

- LCA Article 19, Item 2: Where the employee had a reasonable expectation that the fixed-term contract would be renewed upon its expiration (reflecting the case).

If a non-renewal is deemed impermissible under these provisions, the employer is considered to have accepted the employee's application for renewal of the contract on the same terms as before.

- Determining "Reasonable Expectation of Renewal":

While the case highlighted the importance of "reasonable expectation," defining what constitutes such an expectation has remained a complex, fact-intensive inquiry. Subsequent case law and scholarly analysis have identified various factors, including: the objective nature of the work performed, the character of the contractual position, the employer's statements and conduct regarding renewal, the actual procedures and practices of renewal, and the renewal status of other similarly situated employees. The lack of a definitive, clear-cut framework for assessing this expectation has been a point of discussion. For instance, cases like the R Taxi case showed that such an expectation could be found even at the first renewal, based on recruitment explanations, while other cases, like the S S Y case, denied it despite multiple renewals due to the specific nature of the contractual status. - The Issue of "Non-Renewal Clauses" (Fukōshin Jōkō):

A related issue that has emerged is the effect of "non-renewal clauses" – provisions added to a renewed contract stating that it will be the final renewal. Whether such a clause, agreed to by the employee, can extinguish a previously established reasonable expectation of renewal is debated. Some court decisions have denied the effect of such clauses (e.g., A S case), while others have upheld them if the employee agreed with free will after sufficient explanation (e.g., H G K case, K C B case). Allowing easy validation of such clauses could undermine the protective intent of the principles, given the often-unequal bargaining power at the point of renewal. - The "Reasonable Difference" in Standards Today:

The Court’s assertion that a "reasonable difference" exists in evaluating the justification for non-renewing temporary staff versus dismissing permanent staff needs to be contextualized. While the specific conclusion in the case was based on its facts (temporary workers for fluctuating demand, simplified hiring, independent factory accounting), this rationale should not be over-generalized. Subsequent legislative developments, such as the former Article 20 of the Labor Contract Act (prohibiting unreasonable differences in working conditions between fixed-term and indefinite-term employees) and the Part-Time and Fixed-Term Employment Act (aiming for balanced and fair treatment), place greater emphasis on reducing disparities. Therefore, any claimed "reasonable difference" in treatment regarding job security would likely face stricter scrutiny today, requiring detailed justification based on the specific circumstances of each case rather than a broad assumption based on employment category alone.

Conclusion

The judgment of December 4, 1986, was a seminal ruling in Japanese labor law. By extending the analogous application of dismissal protection to fixed-term contracts based on the employee's reasonable expectation of renewal, it significantly enhanced the job security of fixed-term workers. It clarified that non-renewal is not an unfettered employer prerogative and laid down the rule that an unjustified non-renewal leads to a deemed continuation of the employment relationship. While the Court also acknowledged that the standards for justifying non-renewal might differ from those for permanent employee dismissal depending on the circumstances, this aspect must be viewed through the lens of ongoing legal and societal efforts to ensure fair treatment for all categories of workers. The principles now largely enshrined in the Labor Contract Act, continue to be central to resolving disputes over the expiration of fixed-term employment contracts in Japan.