First Come, First Served? Japan's Supreme Court on Competing Public Bathhouse Permit Applications

A Second Petty Bench Ruling from May 19, 1972

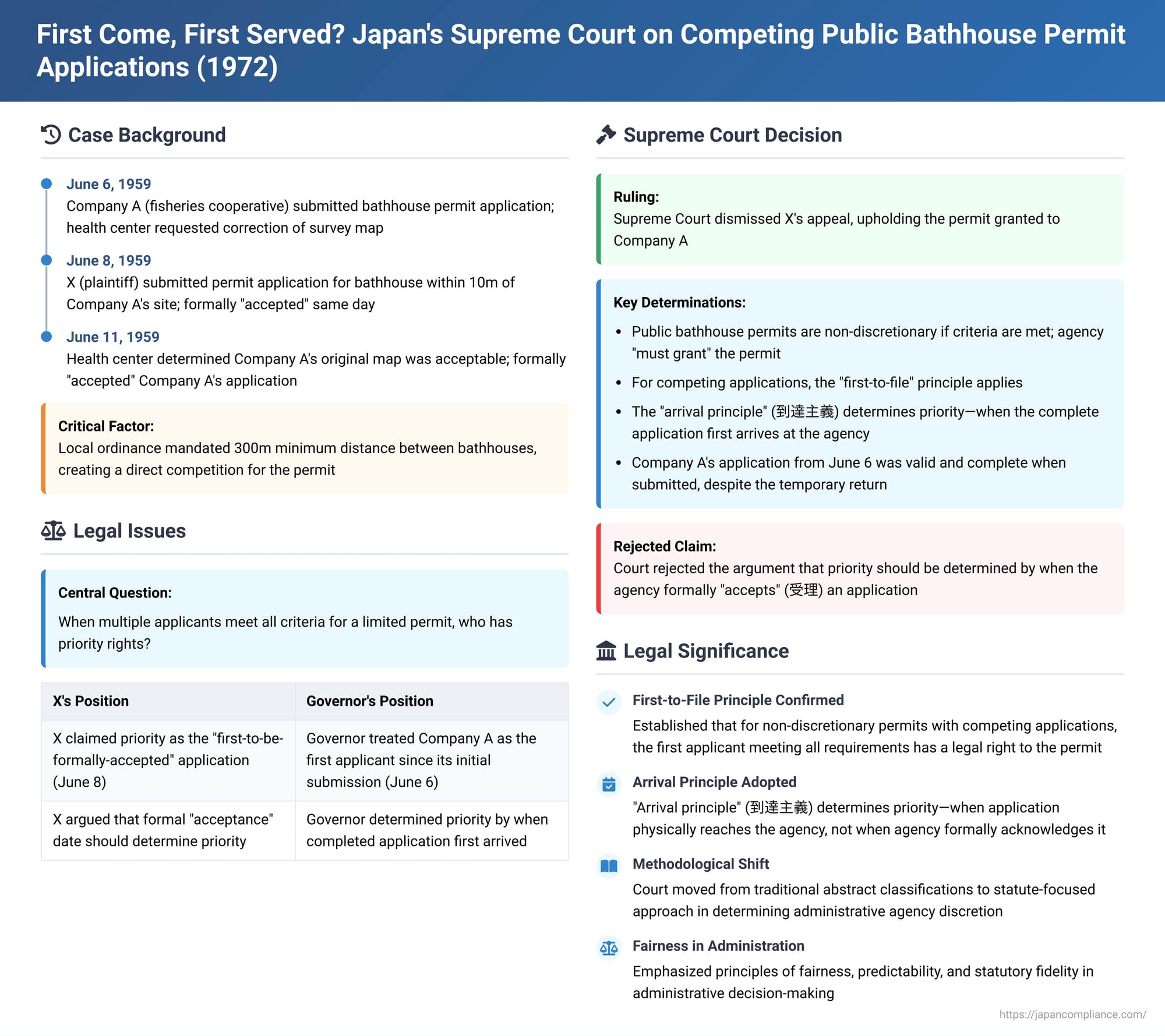

When multiple parties apply for a limited government permit or license, how should the authorities decide who gets it? Does the first person to submit a valid application have a priority right, or does the agency have discretion to choose among qualified applicants? And critically, how is "first" determined—by the moment an application physically arrives at the agency, or by when the agency formally acknowledges or "accepts" it? These questions were at the heart of a 1972 Supreme Court of Japan decision by its Second Petty Bench (Showa 43 (Gyo Tsu) No. 79), in a case involving competing applications to open public bathhouses in Onomichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture.

The Onomichi Bathhouse Race

The dispute involved two aspiring public bathhouse operators:

- Company A: A fisheries cooperative (訴外A - sogai A) that planned to establish a communal bathhouse as a welfare facility for its members. On June 6, 1959, Company A submitted its application for a public bathhouse business permit to the Hiroshima Prefectural Onomichi Public Health Center, the competent authority. However, an official at the health center initially found an issue with the submitted survey map, requesting a correction (a more detailed type of survey). All of Company A's documents were temporarily returned.

- X: The plaintiff/appellant in this case. On June 8, 1959, two days after Company A's initial submission, X applied for a permit to establish a public bathhouse in a location very close to Company A's proposed site—specifically, within 10 meters. X's application was formally "accepted" (受理 - juri) by the health center on the same day, June 8.

Subsequently, on June 11, 1959, it was clarified that the correction initially demanded of Company A's survey map was actually unnecessary, and the map it had submitted on June 6 (prepared by a qualified surveyor using a plane table method) was acceptable. The health center then formally processed Company A's application, with the "acceptance" date noted as June 11.

A critical complicating factor was a Hiroshima prefectural ordinance, enacted pursuant to the Public Bathhouses Act (公衆浴場法 - Kōshū Yokujō Hō). This ordinance stipulated an "appropriate placement standard" (適正配置基準 - tekisei haichi kijun), requiring a minimum distance of 300 meters between existing public bathhouses. Because X's and Company A's proposed locations were so close to each other, only one of them could receive a permit. This created a direct "competing application" (競願関係 - kyōgan kankei) scenario.

Ultimately, Y, the Governor of Hiroshima Prefecture (the defendant/appellee), granted the business permit to Company A and denied X's application.

The Legal Challenge: Who Was First in Line?

X challenged the Governor's decision, arguing that he was the rightful "first-to-file" applicant and that the permit granted to Company A was illegal because it ignored his prior right. X sought a court declaration that Company A's permit was invalid and, alternatively, the annulment of both Company A's permit and the denial of his own application.

The lower courts had differing nuances in their reasoning:

- The Hiroshima District Court (first instance) characterized a public bathhouse permit as what legal scholars term a "police permit" (講学上警察許可 - kōgakujō keisatsu kyoka). This implies that if an applicant meets all statutory requirements, the administrative agency must grant the permit; it is not a discretionary act. In cases of competing applications, the court held, the "first-to-file" principle should apply, and priority should be determined by the "arrival principle" (到達主義 - tōtatsu shugi)—that is, when the application physically reaches the competent authority. It found that Company A's application had effectively "arrived" on June 6, 1959, making Company A the prior applicant. Thus, X's claim was dismissed.

- The Hiroshima High Court (second instance), while acknowledging a general principle of priority for the first applicant, distinguished a public bathhouse permit from a "patent" (特許 - tokkyo, an administrative act creating a special right, like a mining concession, where more discretion is usually involved). It suggested that if applications are submitted almost simultaneously, the administrative agency might retain some discretion in choosing whom to permit. It found no abuse of discretion in the Governor's decision to effectively treat Company A as the first applicant and also dismissed X's appeal. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of May 19, 1972

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, ultimately upholding the Governor's decision to grant the permit to Company A. However, its reasoning clarified important legal principles.

Key Rulings by the Supreme Court:

- Nature of the Public Bathhouse Permit – Non-Discretionary if Criteria Met:

- The Court began by interpreting the Public Bathhouses Act. Article 2, paragraph 2 of the Act allows a prefectural governor to refuse a permit if the proposed location or facility structure is deemed unsuitable from a public health perspective, or if the location "lacks appropriate placement" according to established standards.

- The Court stated that this permit system is primarily a restriction on the freedom of business, imposed from the viewpoint of public welfare, specifically public health and environmental sanitation.

- Critically, the Court interpreted the "purpose and wording" of this provision to mean that if an application meets all prescribed permit criteria (sanitation, proper placement according to distance regulations, etc.), the administrative agency (the Governor) "must grant the permit." It is not a matter of free discretion once the conditions are satisfied.

- First-to-File Principle Applies in Competing Applications:

- Given that the permit is non-discretionary if objective criteria are met, the Court held that in a situation with competing applications (like this one, where the distance regulation meant only one could be approved), if all competing applicants meet the permit criteria and are thus equally qualified, the administrative agency "must grant the permit to the applicant who filed first."

- The Court's rationale was that when a legally compliant permit application that fulfills all requirements is duly filed, a legal relationship is established at that moment between the applicant and the administrative agency, obligating the agency to issue the permit. As long as the permit grant is a legally bound disposition (non-discretionary if criteria are met), this established legal relationship with the first applicant should not be adversely affected by a subsequent application from a third party. A later application can only give rise to a right to a permit if the prior legal relationship with the first applicant is extinguished for some valid reason (e.g., withdrawal of the first application, or its failure to meet criteria) before a permit is issued based on it.

- Determining Priority – The "Arrival Principle" (到達主義 - Tōtatsu Shugi):

- The Court then addressed how to determine who is the "first-to-file" applicant. It rejected the notion that priority should depend on the timing of the administrative agency's act of formal "acceptance" (受付 - uketsuke) or "receipt processing" (受理 - juri) of the application.

- Instead, considering the nature of the public bathhouse permit (as non-discretionary if criteria are met) and the fundamental requirement that all applicants be treated fairly, the Court ruled that the order of priority "should be determined based on the time when the prescribed application documents are submitted to the administrative agency having the authority to receive them." This is known as the "arrival principle"—priority is established when a complete and proper application physically arrives at, or is otherwise duly lodged with, the competent authority.

- Application to the Facts of the Case:

- X submitted his application on June 8, 1959.

- Company A had initially submitted its application, including a survey map prepared by a qualified surveyor, on June 6, 1959. Although an official at the health center had temporarily returned the map requesting a (later deemed unnecessary) correction related to calculation notes, the other application documents had remained with the health center. The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's finding that Company A's application as submitted on June 6, with its survey map, was not improper and already met the requirements for acceptance at that time.

- The Supreme Court emphasized that the health center did not issue a formal decision of non-acceptance (不受理処分 - fujuri shobun) regarding Company A's June 6 submission.

- Therefore, Company A's proper application was effectively "submitted to the competent administrative agency" on June 6, 1959.

- As a result, Company A was determined to be the first-in-time applicant. The Governor's decision to grant the permit to Company A and deny X's subsequent application was, therefore, correct in its ultimate outcome, as it respected Company A's prior right.

X's assertion of having prior rights was thus deemed unfounded, and his appeal was dismissed.

Understanding "Permit" vs. "Patent" and Agency Discretion

This case is notable for how the Supreme Court approached the classification of the administrative act in question.

- Traditional Japanese administrative law scholarship often distinguished between different types of administrative acts, such as a "police permit" (警察許可 - keisatsu kyoka) and a "patent" (特許 - tokkyo). A police permit was generally understood as an act lifting a general prohibition on an activity that individuals are otherwise free to engage in (e.g., for public order or health reasons), and if the applicant met the statutory criteria, the permit was typically considered non-discretionary. A patent, on the other hand, was seen as an act that creates a new, special right for an individual (e.g., the right to operate a public utility), and agencies were often considered to have more discretion in granting patents.

- The lower courts in this case showed some influence from this traditional categorical thinking. The first instance court explicitly called the bathhouse permit a "police permit" to support the first-to-file rule. The second instance, while reaching a different conclusion on discretion in near-simultaneous applications, also referred to the distinction with "patent."

- The Supreme Court, however, significantly departed from this categorical approach. It did not label the public bathhouse permit as either a "police permit" or a "patent." Instead, it focused directly on interpreting the specific provisions of the Public Bathhouses Act. It concluded from the Act's text and purpose (restricting business freedom for public health and welfare, and allowing refusal only on specified grounds) that if the statutory criteria are met, the permit must be granted. This methodology—deriving the nature of the administrative act and the scope of agency discretion from a close reading of the specific empowering statute rather than from pre-defined academic categories—marked an important development in administrative law jurisprudence.

The "Arrival Principle" (到達主義 - Tōtatsu Shugi)

The Court's clear adoption of the "arrival principle" for determining application priority is another key takeaway.

- This principle dictates that the legally relevant time is when a complete application reaches the competent authority, not when the authority internally processes it or formally acknowledges its receipt.

- This approach is seen as promoting fairness and predictability for applicants, as their priority status is determined by their own action of submission and is not subject to potential delays or inconsistencies in an agency's internal handling procedures. This principle had been advocated by legal scholars before this judgment and is generally considered consistent with the aims of ensuring procedural fairness in administrative processes. It aligns with the spirit of later legislation like the Administrative Procedure Act, which emphasizes the agency's duty to promptly examine applications.

Significance of the Ruling

The 1972 Supreme Court decision in this public bathhouse permit case has several important implications:

- Clarification for Competing Applications: It clearly established that for non-discretionary permits, where the granting of one permit precludes others (due to limited slots, distance rules, etc.), the first-to-file applicant who meets all requirements has a legal right to the permit.

- Adoption of the "Arrival Principle": It confirmed that the "arrival principle"—the time of submission to the competent authority—is the correct standard for determining priority among competing applications, rather than the time of the agency's internal act of formal acceptance.

- Shift in Judicial Methodology: Perhaps most significantly, the judgment signaled a move by the Supreme Court towards a more statute-focused approach to determining the nature of administrative acts and the scope of agency discretion, rather than relying heavily on traditional, abstract academic classifications of such acts. This emphasizes a more concrete and textually grounded method of legal interpretation in administrative law. The commentary notes that this judgment was a forerunner in this shift, which later influenced broader academic rethinking of traditional administrative law categories.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's ruling in the Onomichi public bathhouse case provides enduring guidance on how administrative agencies should handle competing applications for permits that are legally mandated if specific criteria are met. By prioritizing the first applicant to duly submit a complete application (the "arrival principle") and by deriving the non-discretionary nature of the permit directly from the governing statute, the Court emphasized principles of fairness, predictability, and statutory fidelity in administrative decision-making. This case remains a key reference for understanding the rights of applicants and the obligations of administrative bodies when demand for limited permits outstrips supply.