Fire Marshal's Consent: Internal Step or Challengeable Act? A 1959 Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: January 29, 1959

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

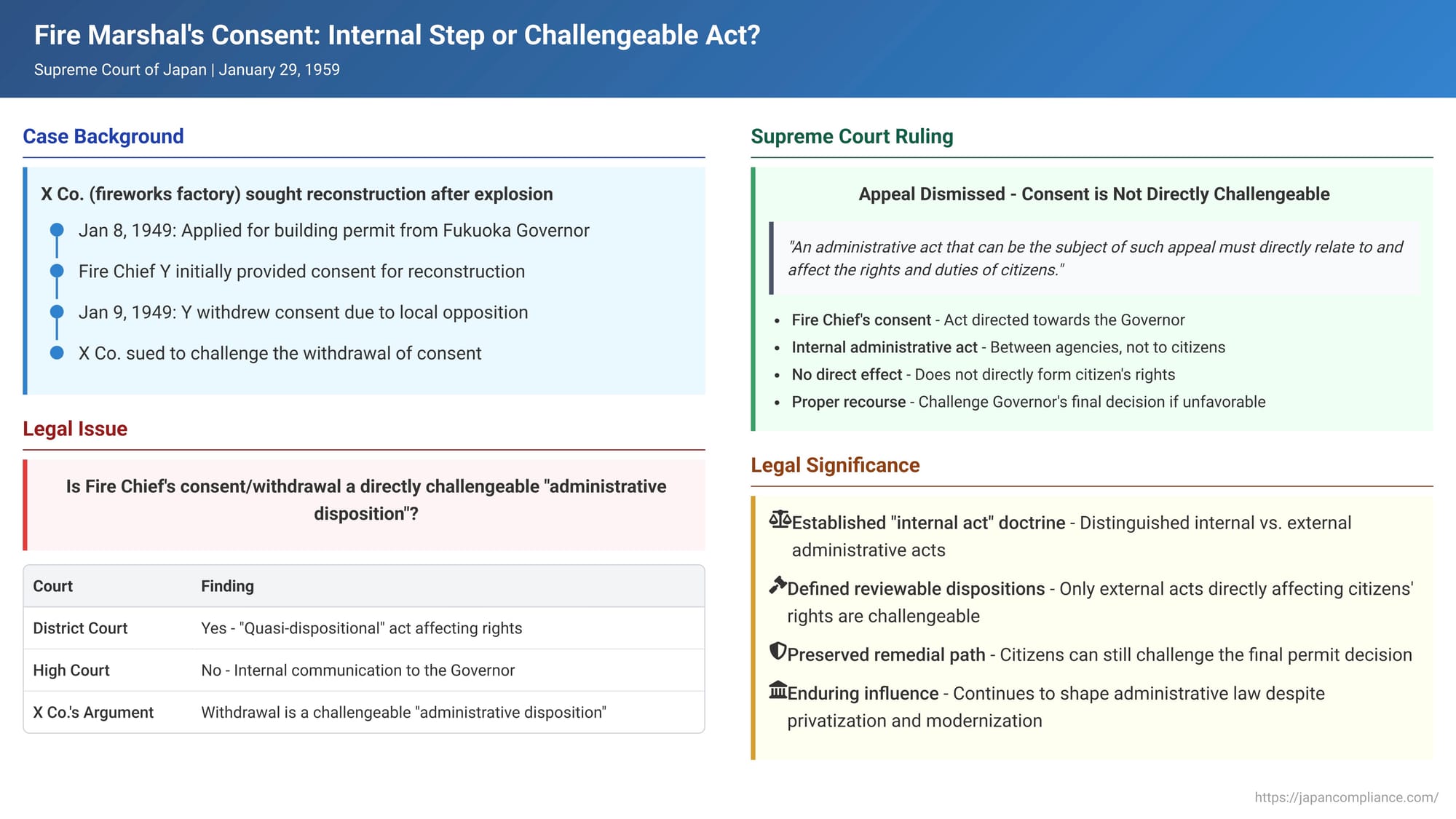

In the complex web of administrative approvals, what happens when one government agency's consent is a prerequisite for another agency to issue a permit to a citizen? Can the citizen directly challenge the first agency's decision if it's unfavorable? A 1959 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed this very issue in the context of a Fire Chief's consent required for a building permit, establishing a key principle about what constitutes a directly reviewable "administrative disposition."

A Fireworks Factory Fire and the Quest for Reconstruction

The case involved X Co., a company that operated a fireworks factory under an existing permit. Following an unfortunate fire caused by a gunpowder explosion which destroyed three of its factory buildings, X Co. sought to rebuild. On January 8, 1949, the company applied to the Governor of Fukuoka Prefecture for a building (reconstruction) permit. At that time, building activities were regulated by the Temporary Building Restriction Regulations.

A critical step in obtaining this building permit was securing the consent of the local Fire Chief. Article 7 of the Fire Service Act (消防法 - Shōbō Hō) mandated this "fire marshal's consent" (shōbō dōi). Accordingly, X Co. approached Y, the Fire Chief of the local village, to obtain his consent for their reconstruction plans.

Initially, Y signed and sealed the consent form presented by X Co. This form was then submitted to the Yanagawa Engineering Office, a local branch of the prefectural government. However, the situation quickly changed. Due to strong opposition from local residents who had previously suffered damage from explosions and fires at X Co.'s factory, Y reconsidered. Believing there was a significant fire safety hazard associated with the reconstruction, Y, around the very next day (January 9th), notified the director of the engineering office that he was withdrawing his consent. He subsequently retrieved the signed consent form from the office.

X Co. viewed this withdrawal of consent by Y as an illegal act. The company filed a lawsuit under the then-applicable Special Law Concerning Administrative Litigation (行政事件訴訟特例法 - Gyōsei Jiken Soshō Tokurei Hō), seeking the revocation of Y's decision to withdraw consent and a judicial confirmation that this withdrawal was invalid.

Lower Courts: Differing Views on the Nature of Fire Chief's Consent

The legal status of the Fire Chief's action was debated in the lower courts:

- The Fukuoka District Court (First Instance), in its judgment on February 28, 1951, actually found that the Fire Chief's consent (or its withdrawal) was more than just an internal administrative matter. It viewed it as an independent act by the Fire Chief, distinct from the Governor, expressing an expert opinion on fire safety. Since this act substantially affected the rights and duties of citizens (like X Co.), the court deemed it at least a "quasi-dispositional" act that could be the subject of a kōkoku soshō (a lawsuit seeking revocation or annulment of an administrative disposition) or a suit for confirmation of invalidity. However, despite this finding on its reviewability, the District Court ultimately dismissed X Co.'s claim for revocation because it had been filed after the statutory deadline. The claim for confirmation of invalidity was also dismissed on the grounds that the alleged defect in Y's action was not "clear and serious" enough to warrant such a declaration. X Co. appealed.

- The Fukuoka High Court (Appeal Court), on February 26, 1954, took a different approach. It held that the Fire Chief's consent under Fire Service Act Article 7 is an expression of will made to the building permit authority (the Governor) concerning fire safety, not an act directed at the building permit applicant (X Co.). Therefore, X Co. should have waited for the Governor's final decision on the building permit application. If the permit was denied (presumably due to lack of fire consent), X Co. could then challenge the Governor's denial of the building permit. The High Court overturned the First Instance's dismissal of the invalidity claim and instead dismissed that claim as procedurally improper. It also found that the First Instance's dismissal of the revocation claim was, in result, appropriate. X Co. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

X Co.'s main argument to the Supreme Court was that Y's (the Fire Chief's) withdrawal of consent was indeed an "administrative disposition" subject to direct legal challenge under the Special Law Concerning Administrative Litigation.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Consent is an Internal Administrative Act

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on January 29, 1959, dismissed X Co.'s appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's conclusion that the Fire Chief's act of withdrawing consent was not directly challengeable by X Co.

Definition of an "Administrative Disposition":

The Supreme Court began by explaining the rationale behind allowing lawsuits to revoke or alter administrative dispositions under the Special Law Concerning Administrative Litigation. Such lawsuits are permitted when:

- The State or a public entity, acting as a subject of public power, performs an act.

- This act is legally recognized as forming or determining the scope of a citizen's rights and duties.

- A citizen whose rights are infringed by such a concrete administrative act can then assert the act's illegality and seek to have its legal effect nullified.

Fire Chief's Consent: Not Directly Affecting Citizen's Rights:

Based on this understanding, the Supreme Court reasoned:

- An administrative act that can be the subject of such a kōkoku appeal must directly relate to and affect the rights and duties of citizens.

- Acts that occur between administrative agencies themselves are generally not subject to kōkoku appeal, unless those inter-agency acts, by themselves, directly form or determine the scope of citizens' rights and duties in relation to the public. This principle also applies to lawsuits seeking a confirmation of an administrative act's invalidity.

- In the present case, the Fire Chief's consent (and by implication, its withdrawal) was an act directed towards the Governor – an act between administrative agencies. It was not recognized as an act that, on its own, directly formed or determined X Co.'s rights and duties in relation to the public.

- Therefore, for the purposes of the Special Law Concerning Administrative Litigation, the Fire Chief's action could not be considered an "administrative disposition" subject to direct litigation by X Co.

Proper Legal Recourse for Applicants:

The Supreme Court concluded that while X Co. could potentially challenge the Governor's final decision to disapprove the building permit application (if such a disapproval occurred) and, within that lawsuit, argue the illegality of the Fire Chief's refusal or withdrawal of consent as a contributing factor to the Governor's decision, a direct lawsuit against the Fire Chief concerning the act of consent withdrawal itself was procedurally improper.

Unpacking the Decision: The "Internal Act" Doctrine

This Supreme Court judgment is a classic articulation of the "internal act" doctrine in Japanese administrative law.

The System of "Fire Marshal's Consent" (Shōbō Dōi):

The underlying legal mechanism involves a two-stage approval process for many building projects.

- Building Confirmation/Permit: Under the Building Standards Act (BSA), a person wishing to construct a building must generally obtain a "building confirmation" (kenchiku kakunin) from a public building official (kenchiku shuji) or, under later reforms, a designated private confirmation and inspection body (DCIB). This confirmation verifies that the building plans comply with relevant building codes and regulations. (The case arose under older regulations requiring a "permit," but the principle is analogous).

- Fire Marshal's Consent: For most types of buildings, the authority issuing the building confirmation (e.g., the building official, or historically the Governor) cannot do so unless it first obtains the consent of the local Fire Chief or Fire Station Chief (Fire Service Act Art. 7(1), BSA Art. 93(1)). The Fire Chief, in turn, is obligated to provide this consent within a specified period if the building plans comply with all laws and regulations related to fire safety (Fire Service Act Art. 7(2), BSA Art. 93(2)).

The purpose of this system is to ensure specialized fire safety review by expert fire authorities while streamlining the process for applicants, who deal primarily with the building permit authority.

Traditional View: Internal vs. External Administrative Relations:

The Supreme Court's decision aligns with a traditional distinction in administrative law theory between:

- Internal administrative acts: Communications, approvals, or directives that occur between different government agencies or officials. These are generally seen as part of the internal workings of the government.

- External administrative acts: Decisions or actions by administrative agencies that are directed at citizens and directly affect their legal rights and duties. Only these external acts typically qualify as "administrative dispositions" (shobun) that can be directly challenged in court.

The Fire Chief's consent to the Governor was classified by the Supreme Court as an internal administrative act. It was a communication from one part of the administration (fire safety) to another (building permits) and did not, in itself, legally alter X Co.'s rights. X Co.'s rights would only be directly affected by the Governor's final decision on the building permit application.

Sufficiency of Remedies Through Challenging the Final Permit Decision:

This "internal act" doctrine was generally not considered to leave applicants without a remedy. As the Supreme Court pointed out, if the lack of fire marshal's consent leads to the denial of the ultimate building permit by the Governor, the applicant can then file a lawsuit to revoke the Governor's denial. In that lawsuit, the applicant would be free to argue that the Governor's decision was illegal precisely because it was based on an unlawful refusal or withdrawal of consent by the Fire Chief. This indirect route was seen as providing sufficient opportunity for judicial review of the fire authority's actions.

Modern Complexities: Privatization and the Evolving Role of "Internal Acts"

While this 1959 judgment represents an orthodox application of administrative law principles, legal commentators note that the administrative landscape has evolved. The privatization of certain public functions, such as the introduction of Designated Confirmation and Inspection Bodies (DCIBs) to issue building confirmations since a 1998 BSA reform, has diversified the actors involved in these processes. DCIBs, though private, now interact with Fire Chiefs to obtain fire consent. This increasing complexity and the blurring of lines between public and private actors in regulatory processes have led some scholars to question whether a strict "internal act" doctrine, which largely shields inter-agency communications from direct judicial review, remains adequate for all situations in modern administrative procedure. They suggest that the legal discipline of such "internal" steps might need reconsideration in light of these systemic changes.

However, the fundamental principle established in this case—that an administrative act must directly affect a citizen's rights and obligations to be considered a challengeable "disposition"—remains a cornerstone of Japanese administrative litigation law.

Conclusion: Affirming a Traditional View While Acknowledging Evolving Administrative Landscapes

The 1959 Supreme Court decision concerning the Fire Chief's consent provides a clear illustration of how Japanese administrative law distinguishes between internal governmental processes and external acts that directly impact citizens. By deeming the Fire Chief's consent to the Governor an internal administrative act, the Court channeled legal challenges towards the final decision-making authority (the Governor issuing or denying the building permit). While the context of administrative procedures has become more complex since this ruling, particularly with the involvement of private entities in regulatory functions, the core principle requiring a direct impact on citizens' rights for an act to be a judicially reviewable "administrative disposition" continues to be a guiding tenet.